|

In 1868 Mr and Mrs Napier celebrated their golden

wedding, and friends came from far and near to offer congratulations

and good wishes for their happiness.

What a change had taken place in these fifty years!

Instead of the obscure mechanic living in a humble dwelling in

Weaver Street, struggling to earn a subsistence for himself and his

young wife, he was now the most prominent business man in the West

of Scotland, his residence a veritable palace, his society courted

by many of the great of the land. Yet in the midst of all his

prosperity, Napier remained essentially a family man, and he loved

to spend his time with her who had been the sharer of his joys and

sorrows through so many long years.

His old friend Sir Spencer Robinson, Controller of

the Navy, writing him on this occasion, said :—

Allow me to hope that your anniversary will be as

prosperous and as happy as we sincerely wish it may be. I quite

understand how short a time fifty years may be to look back upon;

but it is certainly a great and unspeakable blessing to be able to

look back on fifty years of an honoured, useful, successful public

life, shared, assisted, and blessed during that long period by the

closest and dearest of human relations.

Mrs Napier was well known for her sincerity and

uniform kindness to all, and there was constant reference made to

her by her husband's numerous correspondents.

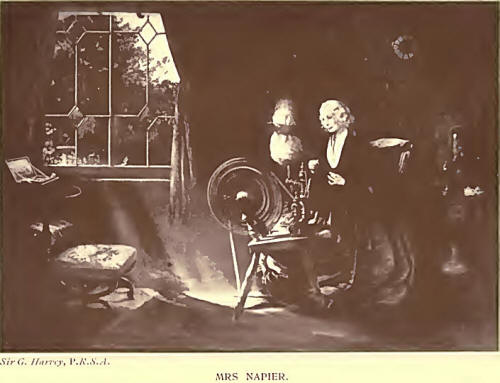

One of her favourite occupations was the spinning of

flax; and Sir George Harvey, President of the Royal Scottish

Academy, painted her portrait in a most characteristic attitude,

seated at her spinning-wheel. Sir George was very pleased with this

work; and having expressed a desire to her Majesty’s Commissioners

that his art should be represented by it in the International

Exhibition of 1872, the picture was publicly exhibited there.

Though Mr Napier had good cause for rejoicing, still

this joy was tempered with sadness, as the number of his friends was

gradually lessening. Most of his early acquaintances, including the

Melvills, Asshe-ton Smith, Wood, Duncan, Cunard, and his old manager

Elder, were gone. From his own immediate circle he had lost his

brother Peter and his three sons-in-law, Hastie, Wilkin, and Rigby.

In 1869 his cousin, David Napier, passed away, and his death was

followed some time afterwards by that of his brother James, with

whom he had been so closely associated.

These partings he felt sorely; but a heavier trial

awaited him. In the autumn of 1875 Mrs Napier, who for some time

before had not been robust, peacefully passed away, leaving his home

desolate. A few lines written to his nephew, James S. Napier,

expressed his feelings :—

“23rd October 1875.

“My dear James,—It is my most melancholy duty to

inform you that about 6 o’clock this night you have lost a kind

friend, and I one of the very best of wives. Inform any friends, as

I am not in a mood to do anything.—Yours always, R. Napier.”

His remaining days were summed up in this pathetic

sentence, “I am not in a mood to do anything.” Up to this time he

had taken an active part in everything going on around him, but this

bereavement so affected him that he ceased to have any special

interest in his former pursuits.

A few months later he was attacked with serious

illness, from which he never rallied, and he died on 23rd June 1876,

in the eighty-sixth year of his age.

To meet the wishes of many friends the funeral was a

public one.

The place of sepulture was adjacent to the old

churchyard of his native town, Dumbarton, where lay the bones of his

ancestors, and where his wife was buried.

On the day of the funeral the inhabitants of

Dumbarton, Helensburgh, and Govan showed their regard by closing

their premises, and special trains from Helensburgh and from Glasgow

brought many hundreds of those who desired to pay the last tribute

of respect.

At Dalreoch Toll the cortege was joined by the

immediate friends of the deceased, and by fourteen hundred of his

workmen, and the sorrowful procession wended its way to the parish

church.

When the company were assembled his eldest son

addressed them as follows :—

I have to thank you for myself, and on behalf of my

brother and sisters, for your kindness at meeting us to-day. It was

my father’s wish, shortly after my mother’s death, that at his own

burial no special invitations should be sent, and we have acted

accordingly. Your presence here to-day shows us more than anything

could do the high respect in which he was held during his life, and

for which we are sincerely grateful. His grief at the loss of my

mother so affected him that he lost all interest in his former

pursuits. About three months ago he became seriously ill, but from

the effects of this he so far recovered as to be able on several

occasions to go out in a carriage for a few miles. But about six

weeks ago he had a second attack, and from this he never recovered,

but got gradually weaker and weaker till lie died. We do not know

whether he suffered pain or not. He was, however, very uneasy till

within twenty-four hours of his death, when he appeared to be

asleep, with an occasional waking up for a short time. We believe he

was sensible to the last.

A service was conducted by his friends the Rev. Dr

Jamieson of St Paul's, Glasgow, and the Rev. Laurie Fogo of Row, and

thereafter the procession being formed up on each side, the coffin

was carried by some of his oldest workmen to its last resting-place. |