|

Although nearly seventy years of age, Mr Napier was

still very active. This is amply proved by the fact that he then

struck out into a new line whereby he increased his fame, making the

building of battleships a special feature of his business.

The Emperor Napoleon III. had given orders for the

construction of an ironclad frigate called the Gloire. This new

departure, coupled with an unusual activity in the French dockyards,

caused disquiet in the mind of the British Government.

To meet the emergency the Admiralty determined to lay

down large sea-going vessels, cased with armour plates; and in the

early part of 1859 they addressed to Messrs Napier a confidential

letter, requesting a design and suggestions for a shot-proof frigate

of 36 guns, cased with 4J-inch armour plates from the upper deck to

five feet below the load waterline, to steam 13J knots, and to be

capable of carrying weights amounting to 1200 tons, in addition to

coals for at least seven days full steaming.

Mr Napier personally went very carefully into the

details of the design, and in the end of February submitted three

models and plans for the proposed ship. Two months later he received

the following letter :—

Admiralty, 3Oth April 1859.

Sir,—I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners of the

Admiralty to thank you for your ready and cheerful compliance with

their wishes, and for the very creditable design furnished by you

for an iron-cased frigate; and am now to request you will state the

price per ton and the shortest time you will require for building a

vessel of this description, the drawings and specification for which

will be ready for inspection at the office of the Surveyor of the

Navy on Monday next. The tenders are to be sent under seal to the

Surveyor of the Navy, marked “Tender for Iron Vessel,” so as to be

received by noon on Saturday the 7th May.—I am, Sir, your obedient

servant, H. Corry.

R. Napier, Esq.

It will be observed that less than a week was given

within which to inspect the drawings and specification and send in a

tender; but yet Mr Napier on 6th May offered to build and engine the

ship within a year for the sum of £283,000 sterling. In his letter

of offer, reference was made to the novelty of the work, and the

difficulty of forming a fair estimate of the cost and time

necessary. There was also a proposal to build the vessel in less

than the time named, if required, leaving the remuneration for

“forced labour” to be determined by the Admiralty.

Mr Napier was not successful in obtaining the

contract for the first frigate, the Warrior, which was given to the

Thames Company, but a few months afterwards, on the 23rd September,

he received intimation that the Commissioners had decided on

building a second vessel, and asking an offer for the hull. A tender

was submitted on the 3rd October, offering to build the ship at £37,

5s. per ton; and three days later this offer was accepted. At first

it was intended to call the ship the Invincible, and on 14th January

1860 my Lords sent notification to this effect. Next day, however,

they issued new instructions, altering the name to the Black Prince.

The building of an ironclad was a task fraught with

much difficulty, as the work was entirely novel. To construct the

vessel, more ground at Govan had to be acquired, and a promise

obtained from the Clyde Trustees that they would deepen the river to

the depth necessary for the launch and safe seaward passage of the

frigate.

The Black Prince measured nearly 420 feet over all,

and her displacement was 9800 tons. She was thus much longer and

heavier than any work which had hitherto been undertaken in Govan

Yard.

The difficulties that arose during construction were

great. Material capable of standing the new tests, which were

rigorously applied, could only be got after long delay and at

enormously increased cost.

The trouble experienced with the massive stern frame,

with the armour plates, with plans, &c., so retarded the work, that

instead of being finished in twelve months as anticipated, the

vessel was over two years in the Clyde under construction.

All obstacles, however, were finally overcome, and

the Black Prince, christened by Miss Napier of Saughfield, entered

the water on 27th February 1861. Her launch was considered such a

great event in Glasgow that it was made the occasion of a public

holiday; and even Professor Lush-ington adjourned his Greek class

with the remark that “this was a sight the Athenians would have

loved to see.” The vessel was taken to Greenock about a fortnight

later to be finished, and she remained there till nearly the end of

the year.

As might have been expected in view of the

circumstances of the case, the contracts for the Warrior and Black

Prince proved most unremunerative to the builders; but while the

Admiralty willingly compensated the English contractor, they

declined to reimburse the Scottish one. This injustice, however, was

not allowed to pass; and eventually, after long delay, Napier got

his claims recognised and his loss in great measure made good.

Many years before this time Mr Napier had acquired

the Parkhead Forge, and the management of it was undertaken by his

son-in-law, Mr Rigby. When ironclads. were being contemplated, Mr

Rigby induced his friend Mr Beardmore, who was then an engineer in

London, to join him, and they took over the Forge, which was carried

on under the style of Messrs Rigby & Beardmore. They put down heavy

rolling-mills, with the intention of making armour plates; but not

succeeding in this the mills were adapted for the production of ship

and boiler plates, in which the firm did a large and profitable

business. Rigby died in 1863, and his widow, advised by the Napiers,

whom he had appointed as his trustees, carried on the business in

conjunction with Mr Beardmore till 1872. Mr William Beardmore, who

succeeded his father, managed to carry out successfully the original

intention of armour-plate making; and eventually, in 1900, with a

view to turning out a ship of war complete, with armour, guns,

engines, &c., he purchased from the Napiers the parent business of

R. Napier & Sons.'

After the successful completion of the Black

Prince the Danish Government commissioned Messrs Napier to build a

war-vessel. In this instance the Danes had such confidence in Mr

Napier’s integrity and uprightness that they made him sole arbiter

in the contract which they entered into with Messrs R.

Napier & Sons.

The Rolf Krake was a handy ship of a new design,

armed with four heavy guns, placed in turrets or shields, as

patented by Captain Cowper Coles. In the war between Denmark and

Prussia in 1866 she gave a good account of herself, being fired at

150 times and coming off unscathed.

She turned the tables completely against the

Prussians; and competent authorities have asserted that if the Danes

had possessed more Rolf Krakes the result of the war would have been

different.

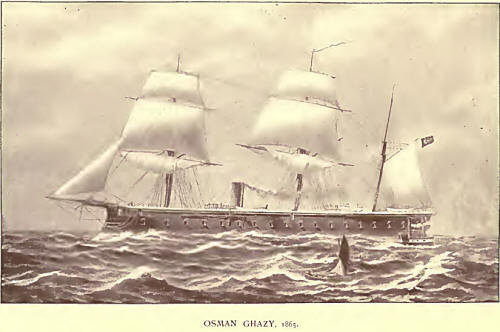

The Turkish Government was the next foreign Power to

requisition his services, and entrusted him with an order for three

large frigates—the Osman Ghazy, the Abdul Aziz, and the Orkhan.

David Livingstone, the celebrated African traveller,

was one of Napier’s acquaintances ; and being in this country in

1865, he was asked to the trial trip of the Osman Ghazy, which was a

great event. Livingstone’s reply to this invitation will be read

with interest, containing, as it does, a glimpse of his private

life.

Burnbank Road, Hamilton,

24th June 1865.

My dear Mr Napier,—I thank you very much for kindly

remembering me in the launch and trial trip.

I shall be unable to avail myself of the pleasure of

seeing the launch; but I should like so very much to see an ironclad

performing under your superintendence, that if possible I shall be

present at the trial trip of Osman Ghazy on Wednesday.

In giving the usual intimation to my friends, I quite

forgot to send one to you and Mrs Napier about the death of my

mother, aged eighty-two.

She said to me, when going away seven years ago, that

she would like to have one of her “laddies” to lay her head in the

grave. That wish was granted, for I performed the last duty to her

yesterday.

Tell Mrs Napier that the great change appeared only

an hour before the close in quicker breathing. My sister said, “I

think the Saviour has come for you, mother; you can lippen yourself

to Him.” “Oh yes,” she said in a way that only we Scotch can

understand, gave a last look to our little girl, and said, “bonnie

wee lassie,” closed her eyes, and soon all was over.

We are thankful to believe she is safe in the haven

of mercy. These little things we mention only to friends who can

appreciate them.—Ever yours, David Livingstone.

After finishing the warships for the Sultan, Napier

was commissioned by the Netherlands Government to build for them two

coast defence vessels, the De Buffet and De Tijger.

Further contracts for large warships for the British

Navy followed, and the stream of orders from this source flowed

henceforth uninterruptedly.

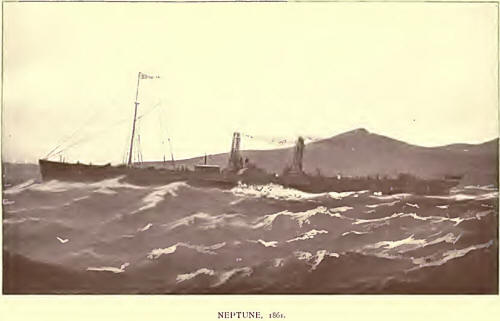

While engaged on this heavy class of work, Messrs

Napier found time to construct a river steamer, the Neptune, with

which they emulated the success attained in early days by

theClarence.

The Neptime was a very fast boat, and had many

features that were then novelties, such as double diagonal engines

running at high speed, Gifford’s patent injectors, superheaters in

the funnel uptakes, very small paddle-wheels, iron floats, &c., &c.

Mr Dunsmuir, now of Messrs Dunsmuir & Jackson, was

placed in charge of the engine-room, and in his hands she was the

swiftest vessel on the river, attaining a speed of 21 miles an hour,

with engines making seventy-three revolutions per minute. After

running two seasons on the Clyde she was sold to run the American

blockade between Havanna and Mobile, Dunsmuir agreeing to go with

her.

On her way out she was nearly wrecked off the coast

of Portugal, having been navigated too near the shore among

breakers. She was given up as lost, and no doubt would have been but

for her great engine power, by which she was literally dragged

through the surf, which was breaking over her, and thus made a very

narrow escape. When coaling at St Thomas she was watched by

the Washita, one of the fastest cruisers in the American Navy,

commanded by the daring Admiral Wilkes, of Mason and Sliddell fame.

No sooner had the Neptune cleared the harbour than it was seen that

the cruiser was pursuing her. The chase was maintained ail day, but

before daylight disappeared the Washita was left hull down on the

horizon. All night the Neptune was kept going at her top speed, and

by next morning there was no appearance of her pursuer.

There were several very hot runs about Cuba, but she

managed successfully to pass four times through Admiral Farragut’s

blockading squadron. On one of these ventures she was nearly

captured, having gone on a sand-bank during the night at the

critical juncture of passing through the fleet. She remained aground

for about three hours. During all this time the engines were kept

going at full speed, and at daybreak she had the good fortune to

pull off. Had the vessel not been exceptionally strong, it is

evident she could not have stood the very rough treatment she

continually received.

The profits on blockade-running were enormous,

amounting in this case to £15,000 a trip; and Dunsmuir, on whom so

much depended, was only receiving £100 for the double run.

After the fourth successful run, he very reasonably

requested that his remuneration should be doubled; but the owners

refusing this, he resigned with regret, and on the next attempt

the Neptune was captured.

She was taken as a prize to Norfolk, in Chesapeake

Bay, and used by the Northern States for watching other block-ade-runners.

In 1861-62 two vessels were built for the Cunard

Company,—the paddle-steamer Scotia, and a screw-steamer called

the China. The days of the Atlantic paddle-steamer were numbered;

and it may be mentioned that in the letter inviting the tender for

the Scotia there is reference to the possibility

of her ultimate transformation into a screw, and

provision was to be made for doing so. This change actually took

place some years later, when she was purchased by the Telegraph

Construction and Maintenance Company, and converted into a twin

screw. These two vessels were the last ordered by the Cunard Company

from Mr Napier.

In 1864 he undertook to build two large fast screw

steamers for the Compagnie Gendrale Transatlantique—viz., the Pereire and

the Ville de Paris. With these the blue ribbon of the Atlantic was

wrested from their British competitors.

Mr Napier had previous experience of the generosity

of the French, since he had attended the great Exhibition of 1855 in

an official capacity, and had then been created a Chevalier of the

Legion of Honour. Now he was extolled and feted by them; and when

present at the Exhibition of 1867 the Empress Eugenie was so struck

with his dignified appearance that she requested that he should be

specially presented to her.

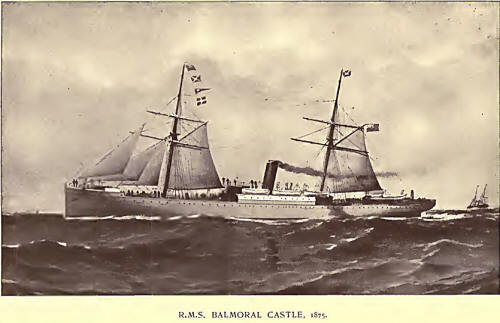

Another connection he formed was with Sir Donald

Currie, who entrusted the construction first of his sailing-ships

and afterwards the greater part of his fleet of Cape mail - steamers

to Mr Napier’s firm.

Special reference may also be made to the contract he

received from his old customers, the Indian Government, for the

troopship Malabar. This magnificent specimen of naval architecture,

designed by Sir E. J. Reed, was sister ship to the Serapis, which

was chosen as the vessel most suitable for his Majesty the King

when, as Prince of Wales, he visited India.

In 1870 Messrs Devitt & Moore ordered a large steamer

called the Queen of the Thames. It was the intention of her owners

to run steamers to Australia capable of making the passage in forty

days; and this was the pioneer vessel. Messrs Devitt & Moore

contemplated building six vessels of her type to maintain the

service, but most unfortunately the steamer on her first homeward

passage was wrecked at Cape Agulhas, and in consequence the

enterprise was abandoned.

Ten years later the scheme was again revived by

Messrs George Thompson & Co., and brought to a successful

issue,—Messrs Napiers’ firm, of which Dr Kirk was then the head,

constructing the Aberdeen, the first vessel fitted with triple -

expansion engines.

The Dutch Transatlantic Company in 1871 favoured Mr

Napier with a large order; and his former friends the Pacific

Company returned to him. Contracts such as these, along with

numerous important Government orders, kept his Works well employed.

Competition gradually grew keener; but Mr Napier

always insisted that the quality of work turned out by his firm must

be of the very best. When it was suggested to him that the

exigencies of the times required cheaper methods, he would hear of

none of them, saying he would, if need be, retire from business, but

that his name must never be associated with work that could be

considered in any way inferior.

As years pressed on him the active management

devolved more and more on his son, Mr John Napier, but the

conditions with which he was confronted made it impossible to carry

on the Works profitably. Mr John Napier never shrank from his

difficult task; but though an able engineer, his attention was so

taken up with the general management of affairs that few

opportunities were afforded him of indulging his mechanical bent. It

was, however, at his instance that “the measured mile” at Skelmorlie,

which is still considered the best of its kind in the kingdom, was

laid out and measured, and letters were addressed to all the

shipbuilders in the following terms :—

“Lancefield House, Glasgow, 30^ August 1866.

“Dear Sirs,—We beg respectfully to state that having

long felt the want on the Clyde of a correct measured nautical mile

for testing the speed of large steamers (similar to what the

Admiralty have near Portsmouth and elsewhere), we had the shores of

the Clyde examined for a suitable place for laying off a knot; and

finding that from Skelmorlie Pier southwards would answer the

purpose, we applied to the Right Hon. the Earl of Eglinton for

liberty to erect beacons on his property. This the Earl at once most

kindly gave full permission to do. We then employed Messrs Kyle & Frew,

along with Messrs Smith & Wharrie, Land Surveyors, Glasgow, to

measure and lay off a knot, which they did; and thereafter we made

application to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, begging as

a favour that .they would send one of their officers to remeasure

and test the correctness of this knot, and we would willingly bear

the expense. Their Lordships were pleased to accede to our request,

and afterwards intimated to us that the knot had been duly tested by

their officers and found correct. At the same time they declined to

make any charge.

“Their Lordships have caused a printed notice to

mariners to be issued from the Hydrographic Department of the

Admiralty, of which the annexed is a copy.—We are, dear Sirs, your

obedient servants,

“R. Napier & Sons.”

NOTICE TO MARINERS.

No. 36.

Scotland—West Coast.

Measured Mile in Firth of Clyde.

Notice is hereby given that beacons to indicate the

length of a nautical mile (6080 feet), for testing the speed of

steam-vessels, have been erccted on the eastern shore of the Firth

of Clyde.

Each beacon consists of a single pole 45 feet high

with two arms 10 feet long forming a broad angle 15 feet from the

base, the whole being painted white.

The two northern beacons are erected near Skelmorlie

Pier, the outer one being close to the high-water shore on the south

side, and from it the inner one (in a recess of a cliff) is 83 yards

distant, bearing S.E. by E. f E.

The two southern beacons stand on level ground near

Skelmorlie Castle, the inner one being 100 yards from the outer one,

in a S.E by E. f E. direction.

The courses parallel with the measured mile at right

angles to the line of transit of the beacons are N.N.E. { E. and

S.S.W. { W. The shore may be approached to the distance of a third

of a mile.

Geo. Henry Richards, Hydrographer.

Hydrographic Office, Admiralty,

London, 4th July 1866.

One of Mr Napier’s last public appearances was at a

large social gathering of his workmen, held in the City Hall in

1868, over which he presided. At this reunion he related to his

employees for their encouragement the story of his early struggles,

and displayed as a token of his former skill the hammer-head,

already referred to, which he had made more than fifty years

previously.

Although he now rarely visited his Works, he was as

active as ever in the social sphere, and continued to dispense

open-handed hospitality at his house at West Shandon. He was in the

habit of

getting letters such as the following one, and these

always called forth a cordial response :—

195 West George Street, Thursday, ls< October 1874.

My dear Sir,—I have been encouraged by my mother, who

has the pleasure of knowing you, to claim your acquaintance as a

member of the name; and I propose to do myself the honour of paying

you a visit at Shandon on the afternoon of Saturday next, if it is

convenient to you to receive me.

I am staying with Mr and Mrs C. Tennant during the

meeting of the Social Science Congress, and Mrs Tennant will avail

herself of the same occasion to pay her respects to Mrs

Napier.—Believe me, my dear Sir, yours very faithfully, Napier

and Ettrick.

Almost every person of note who came to the West of

Scotland called upon him; and special mention may be made of the

visit which the Princess Louise paid to West Shandon shortly after

her marriage with the Marquis of Lorne. Her Royal

Highness was so delighted with her host that she sent

him her photograph us a souvenir.

In his closing years honours flowed in upon him from

all quarters.

Reference has already been made to his connection

with the French Exhibitions; and in a similar capacity he acted as

Chairman of the Jury on Naval Architecture at the London Exhibition

of 1862.

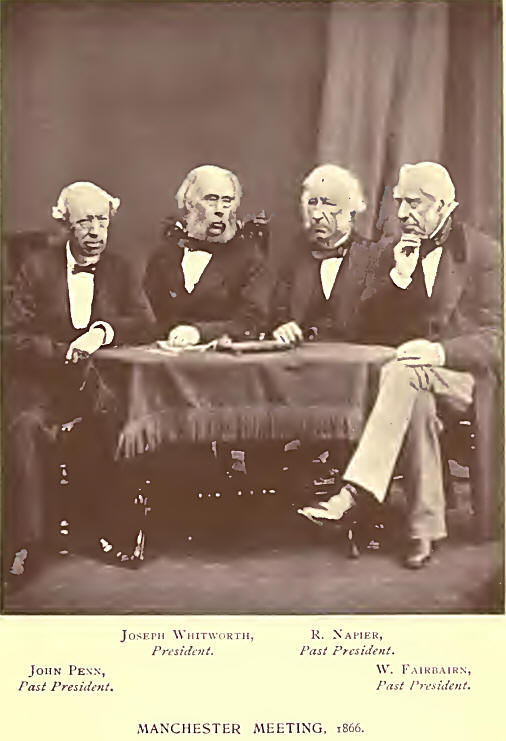

The Institution of Mechanical Engineers, of which he

was a prominent member, elected him as their president in 1864, a

distinction he enjoyed in common with his friends Fairbairn, Penn,

and Whitworth.

He was also one of three honorary members elected by

the Glasgow Society of Engineers in 1869, the other two being

Fairbairn and Sir William Thomson, now better known as Lord Kelvin.

In the same year the King of Denmark, desirous of

recognising his services to naval architecture, conferred on him the

honour of Knight Commander of the Danne-brog. A prominent naval

officer, congratulating him on the occasion, wrote :—

I have rejoiced that the King of Denmark has shown a

proper spirit in conferring on you the honour of one of Denmark’s

Orders, and may our Queen be induced to show her appreciation of

your valuable services to our Navy by conferring a similar honour in

the shape of a K.C.B. Why not? for, as Jack says, ‘You builds ’em;

we sails ’em.’ Long may you be spared to enjoy what you have already

gained.

This omission was commented on at the time of

Napier’s death, one of the papers boldly saying : “Her Majesty alone

seems to have been negligent in recognising his genius by any

distinguishing mark of royal favour, an omission which does little

credit to the successive Governments which profited by his skill,

and should have advised her Majesty of the opportunity afforded to

her.”

This apparent overlook might to a certain extent be

accounted for by the fact that Mr Napier was not a politician, and

he never was in any sense of the word a place-seeker.

Titles, however, are evanescent, being of more

importance in the eyes of contemporaries than in those of their

descendants; and posterity will know Robert Napier by a greater

designation as the father of modern shipbuilding. |