|

By the middle of the century Robert Napier was at the

zenith of his greatness and fame. He had successfully introduced on

the Clyde iron shipbuilding for large vessels, and other firms that

had sprung from him were developing the industry.

Being now sixty years of age, he was desirous of

greater leisure, that he might enjoy to some extent the fruit of his

arduous labours. His intentions for the future were that his

business should be actively carried on by his two surviving sons,

James and John, assisted by his son-in-law, Mr Rigby, and his

nephew, James S. Napier ; and with this purpose in view he had left

Glasgow, and now resided permanently at West Shandon, on the shores

of the Gareloch.

In the meantime the Pacific Steam Navigation Company,

with whom he was much associated, had arranged for an extension of

their mail service, and placed a contract with him for four large

paddle-steamers— the Santiago, Lima, Bogota, and Quito. At this time

the building-yard at Govan was managed by Mr James R. Napier, and

the engine-works at Lancefield and Vulcan by Mr Elder, in

conjunction with Mr John Napier, Mr Elder’s son John occupying the

position of chief draughtsman.

The managing director of the Pacific Company, Mr

Just, who was on terms of intimacy with all parties, gave

instructions to the respective managers, who complied with his

wishes; but in doing so due consideration was not paid to one of the

conditions of the contract, which was treated as of little

importance. This condition was that the vessels should steam at the

rate of 12 knots with 500 tons on board, this weight being 150 to

200 tons beyond the maximum weight the vessels were intended to

carry on their regular voyages.

When tried at full load-draft the paddle-wheels of

the Santiago were too deeply immersed, and as the required speed in

this condition was not attained, the Company declined to accept the

vessel. Mr Napier was much annoyed, as Mr Just’s instructions had

been complied with, and the failure was due in large measure to

alterations from the original plans. If his object had been solely

to fulfil the guarantee as to speed rather than serve the Company,

he could, by reducing the paddle-wheels (which would have cost

little), have made the vessel steam 12 knots with the stipulated

weight, but she would then have been useless in ordinary sea-going

conditions. However, in his anxiety to please he altered

the Santiago at great expense, so that she might fulfil the literal

terms of the contract and prove a useful steamer. But he did not

think that the directors used him well in claiming to exact

penalties for delay in delivery, and in consequence he was not

desirous of building more vessels for them.

At this juncture John Elder, who as chief draughtsman

had much to do with the Santiago difficulty, desired to leave, and

on 27th August 1852 wrote to his employer in the following terms :—

Dear Sir,—In compliance with the liberty granted me

in your favour of the 18th March and the 16th June, I have arranged

to join Messrs Randolph Elliott & Company. I shall therefore feel

obliged by your informing me what day I might consider myself clear

of my engagement with you, and beg to state that I have done

everything in my power for the last five months to render this

change in the sub-management of your establishment as gradual as

possible; and if there is anything else could be done by me either

before or after my dismissal it will give me much pleasure to avail

myself of the opportunity.

The 1st of September next is my quarter day, and, if

convenient, I should like* to close with you and your sons at that

time.—I am, dear Sir, yours very truly, John Elder.

John Elder’s agreement was entered into in 1846, and

did not expire for some time. There was no question of dismissal, as

Mr Napier was sorry to lose his services; but he reluctantly

assented to his request to depart on four days’ notice.

The Pacific Company found John Elder an eager

competitor for their orders. As is well known, he introduced into

the mercantile marine the compound engine, with its consequent

reduction of coal consumption. To the Pacific Company, with their

South American service, this saving in coal was of enormous

advantage, and they became his chief supporters, ordering many

vessels from his firm, and continuing to do so till the date of Mr

Elder’s death, which took place in 1869.

We may remark on the intimate connection between the

Napier and Elder firms.

Randolph, the founder of the latter, was brought up

in Napier’s works, and started in business for himself in 1834.

After John Elder joined him they began shipbuilding in Napier’s old

yard at Go van. On Mr Elder’s death, Mr (afterwards Sir) William

Pearce, who then acted as manager of Messrs Napier’s ship-yard, was

asked to take the position of shipbuilding partner at Fairfield. He

was under a long engagement with the Napiers, but they readily

acceded to proposals for his advancement, and consented to his

departure. A few years later he became sole partner, and did much to

enhance the reputation of the Clyde as a shipbuilding centre, his

chief triumphs being the Cunard steamers Umbria and Etruria, in the

construction of which he was ably assisted by Mr Shepherd, who

succeeded him at Napier’s establishment, and afterwards followed him

to Fairfield.

When John Elder was leaving, Mr A. C. Kirk was

entering on his apprenticeship at Vulcan Foundry. This most talented

engineer, on completion of his indenture, went to London, where he

occupied a prominent position in Messrs Maudslays’ establishment. On

his return to Scotland he became manager of Messrs Youngs’ Paraffin

Works, where he revolutionised the industry. A few years later he

took charge of Messrs Elders’ Engine-Works, and superintended their

transference from Centre Street to the present premises at

Fairfield.

On the death of Mr Napier he, with others, acquired

the business of R. Napier & Sons, and in his capacity as senior

partner upheld the firm’s reputation. He took an active part in the

introduction of steel into shipbuilding, and built the Parisian, the

first Atlantic mail-steamer constructed of the new material. In 1881

he successfully introduced into the mercantile marine the triple

expansion engine, which has since been universally adopted; and a

few years later was entrusted by the Russian and British Governments

with their first orders for this class of machinery. The last

mail-steamer he engined was the Orient liner Ophir, which was

selected as the vessel best suited for the conveyance of their Royal

Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales in their tour of the

British dominions,—a service which she performed to the satisfaction

of all.

Even at the present day the connection is maintained,

Mr Gracie, the well-known director of engineering at Fairfield,

being an old Napier apprentice.

In 1853 Mr Napier adopted his sons as partners, and

altered the style of his firm to “ Robert Napier & Sons," under

which designation it was henceforth known. This was a preliminary

move, but unfortunately the change was not a success; and within a

few months we find him regretting the step he had taken, and making

up his mind to revert to the old “Robert Napier,” which he did in

deed if not in name.

Mention may here be made of an interesting episode

illustrating the peculiar attitude which the British Government

occasionally adopts towards its subjects.

Shortly before the Crimean War the Russian Government

ordered some engines from Napier, and when the war-cloud darkened,

in view of possible hostilities they sold them to a German firm. On

declaration of war the British Government seized this machinery,

although technically it was the property of a neutral, and promptly

despatched an official, who placed the broad arrow on the engines,

and arranged to have them watched day and night.

Owing to the sale effected by the Russians, the

position of matters was complicated, and Napier sought the

protection of his Government, offering to complete the engines, and

deliver them to the Admiralty, provided he was indemnified against

any claims that might arise.

Instead of acceding to this apparently reasonable

proposal, the Government officials coolly made a claim on him for

the expense of watching the property which they had confiscated.

Napier promptly refused their demand, and had

recourse to his friends in the House of Commons, through whom

pressure was brought to bear whereby his position was properly

recognised, and he obtained the desired protection.

The British Government ultimately took the engines in

accordance with Napier’s suggestion, and they were fitted on board

H.M. ships Urgent and Transit. The latter vessel, it may be

observed, had a somewhat unfortunate career, and was finally wrecked

on the coast of China.

The dimensions of vessels were in the meantime still

increasing; so, to meet the growing requirements of shipowners,

Napier purchased more ground at Go van, and laid out a new yard

where he could build vessels up to 400 feet long.

Owing to the conditions of the Government subsidy,

the Cunard company had hitherto built wooden vessels for their mail

service; but now they resolved to adopt iron, and gave out the

contract for the Persia.

This vessel was a great advance on anything hitherto

built on the Clyde, and her design was a long time under

consideration. In the beginning of March 1852 we find Napier writing

Mr C. Maclver that “he was studiously considering the Persia” and in

August of the same year he arranged to make the engines for the sum

of £45,000. It was not till a year later that the contract for the

hull was settled, and there is an interesting letter on this

subject. Writing from West Shandon on 3rd August 1853 to Mr Maclver,

he says :—

“My dear Sir,—Yesterday I arranged with Mr Burns for

the building of your large iron steamer, and recommended she should

be made about fifteen feet longer and from one to two feet lower. Mr

Burns stated nothing could be done in Glasgow on that score, the

whole rested with you. I therefore think it best, after a day's

consideration of the subject, to write you direct, and to state that

my people are to go over the details of the specification with Mr R.

Thomson previous to the same being laid before you for approval. But

as the dimensions are what R. Thomson cannot touch, I have to

request that you give the following your immediate consideration and

attention, as I am most uneasy regarding the success of this vessel

as a whole ; for I am convinced, unless the greatest care,

attention, and judgment are exercised in the getting up of this

large vessel with a limited power, that there is a very great risk

of failure in one thing or another. On the other hand, if care is

taken, and we are not unnecessarily tramelled as to dimensions,

&c., I have no fears but that a good result will be obtained, and I

think from the past experience had of my character in such matters

you may have every confidence that I shall not propose or recommend

anything to you that is at all likely not fully to answer its

purpose.”

Then follow the technical details, and the letter

closes with the remark—

“Excuse my anxiety as to this vessel.— Yours

faithfully, R. Napier.

“C. MacIver, Esq.”

The consideration of dimensions and plans extended

over many months, and it was the summer of 1854 before work was

fairly started.

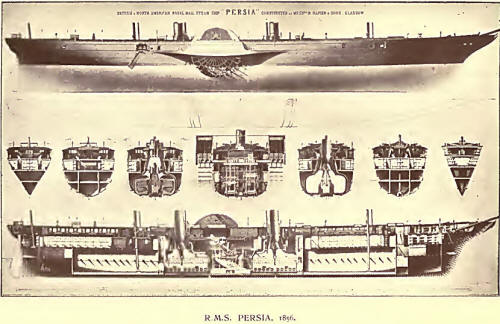

The Persia was 390 feet over all by 45 feet beam,

having a gross tonnage of 3600 tons. She had double side-lever

engines, with cylinders 100J inches in diameter, a stroke of 10

feet, and wheels fully 40 feet in diameter. Everything that care and

skill could devise to make her a strong and a safe ship was done.

Her frames were spaced 18 inches apart, and at the

bow were placed diagonally, with a view to greater strength in the

event of a collision. This arrangement stood her in good stead when

on one occasion she ran into an iceberg stem on, and escaped with

slight damage. Her cabins were of the most sumptuous description,

and accommodation was provided for nearly 300 passengers. Her cost

was about £130,000, and at the time of her launch, which took place

in the presence of 50,000 people, she was the finest and largest

vessel afloat.

She was tried in January 1856, and steamed from the

Cloch Lighthouse to Bell Buoy, a distance of 175 knots, in 10 hours

43 minutes, this speed working out at the rate of over 16 knots an

hour.

At the trial trip, in proposing the health of the

builder, Mr Burns said, “Mr Napier had built forty large vessels for

the Company’s lines, and there never had been a fault or a mistake

from the starting to the carrying out of any one of them. This was

saying a vast deal, but they were so indebted to him.”

The Persia may be considered the first of the

Atlantic greyhounds. She added much to the prestige of the Cunard

Company, it being humorously observed in reference to her builder,

“She has nae peer on the Atlantic.” Even the English papers wrote,

“It must be confessed she is the finest ship afloat. What can be

done by others is one thing, what has been done by Mr Napier is

another.” Mr Kirkcaldy drew a sectional plan of her, which had the

unique distinction of being the only mechanical drawing ever

exhibited at the Royal Academy.

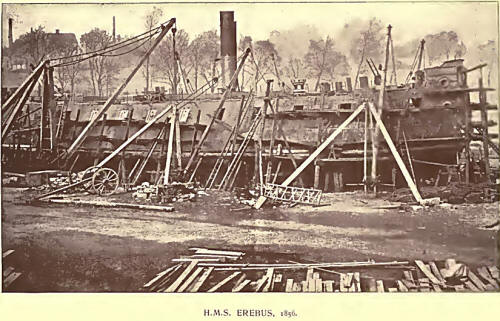

During the Crimean War the Government ordered from

London and elsewhere wooden ships cased with iron plates; but as

these were not a success, they commissioned Napier to build an iron

vessel of a similar description. She was called the Erebus, and the

most extraordinary exertions were put forth to construct her

rapidly, as the contract was taken with a penalty of £1000 a-day.

She was 186 feet long by 48½ feet broad, and was cased with 4½-inch

armour plates placed on 6-inch teak backing. The work was pushed on

night and day, no fewer than 1200 men being employed on her

construction. Laid down in the beginning of the year, she was

launched, with her machinery on board, on 19th April 1856, having

been only three and a half months in hand. She left next day for

Portsmouth, and reached Spithead at the close of the naval review

held then on 23rd April. The credit for this exploit was largely due

to Mr James R. Napier, but the strain told severely on his health,

and soon afterwards he retired from the firm.

James R. Napier, while not a practical business man,

was possessed of high scientific attainments. Educated at Glasgow

University, where he took a high place in the mathematical classes

taught by Professor Thomson, the father of Lord Kelvin, he applied

his knowledge to marine architecture, and was one of the first to

investigate theoretically the intricate question of strains in iron

vessels. He was an intimate friend of Professor Rankine, who joined

with him and others in writing a treatise on shipbuilding, which was

recognised as a standard work.

He also instituted elaborate measured mile trials

(now so universal) for the purpose of acquiring accurate data

regarding the performances of vessels. He was an advocate of hollow

water-lines, and had strong views on this subject which were

exemplified in a steamer called the Atlmnasian, built by him to

illustrate them.

After retiral from business he devoted his time to

scientific pursuits, and his society was much cultivated by Lord

Kelvin, in conjunction with whom many abstruse problems were

investigated.

He made several long sea voyages, and devoted special

attention to matters connected with navigation, such as perfecting

compasses and methods of obtaining rapidly deep sea soundings, ideas

which his friend Lord Kelvin afterwards brought to perfection.

He built a fishing steamer called the Islesman, in

which were embodied most of the ideas to be found in the modern

well-trawler.

For ordinary domestic wants he patented stoves, and

an apparatus for making coffee which is still unsurpassed, and known

by the familiar name of “The Napier Coffee-pot".

An active member of the Glasgow Philosophical

Society, he took a great interest in similar institutions, including

the British Association and the Royal Society of London, which

recognised his attainments by electing him a Fellow.

On the retiral of his eldest son the business was

carried on by Mr Napier and his second son John, who attended most

diligently to the affairs of the concern, assisted by able managers

whom he selected, such as Mr Walter Brock, now of Messrs Denny

& Co., Mr Pearce, Mr Shanks, and others.

Advances were made to Mr James S. Napier to resume

his connection with the firm, but though the relationship was most

intimate and cordial he preferred to remain outside. No partnership

was offered to any others, and Mr Napier and his son remained the

sole partners till the date of the former’s death.

Mr Napier took a warm interest in the affairs of the

City of Glasgow, but he never aspired to municipal honours, though

his son-in-law Mr Alexander Hastie was Lord Provost, and represented

the City in Parliament.

In 1857, at the time of the disasters to the Western

and City of Glasgow Banks, there was great distress, and Mr Burns,

who had been interested in the Western Bank, wrote Mr Napier as

follows :—

Glasgow, 27th November 1857.

My dear Sir,—A deputation is going to Government on

the present state of money matters here, and I have been requested

to beg most urgently that you will join it. You will not be asked to

do anything more than show face; but that is considered of

consequence, and I am sure you will be willing to lend a helping

hand.—Yours very truly, G. Burns.

To Robert Napier, Esq.,

Golden Cross, London.

The deputation was to consist of the Lord Provost and

some leading men; and in the letter intimating to Mr Napier that he

had been nominated, Mr Crichton says: “You have been selected as

being the employer of a very large number of mechanics, and as being

perhaps better known to the Government than any other private

citizen of Glasgow.”

Mr Napier, however, while sympathising with the

distress, did not see his way to join in the movement, which came to

nothing.

One outcome of the visit which her Majesty Queen

Victoria paid to Glasgow in 1849 was a revival of interest in the

Cathedral; and a movement was set on foot to improve the edifice,

and introduce stained glass windows in the aisle to give a dim

religious light. In this scheme Mr Napier took a great interest, and

he wrote Sir Andrew Orr, who was then Lord Provost, expressing his

views.

“West Shandon, 21s£ Ap'il 1857.

“My dear Lord Provost,—I am favoured with your note

of yesterday requesting me to attend a meeting of Committee on

Friday next to consider the Report upon Cathedral Windows.

“I am sorry that a previous engagement for that day

(and which I cannot get off from) will prevent me from being

present.

“I have, however, much pleasure in stating that I

consider Mr Stirling and the gentlemen who drew up the report

deserve the best thanks of the subscribers for the careful, clear,

and concise manner in which they have placed the whole subject

connected with this painted glass movement before all who are

interested in it.

"I notice that the feeling of the Committee is

decidedly in favour of employing foreign artists. Seeing such is the

case, I will not dissent, although I would have liked that native

artists had had a chance. But I do dissent from giving the order to

the royal factory at Munich, or to any other party, without a more

careful examination of the matter than has yet been done. I

do not object to the high price of the Munich glass if it really is

so much better than other painted glass. I have, however, my doubts

on this subject; and in this I am strengthened by the enclosed

letter received from Mr M‘George, and also by the opinion of others.

I quite agree with the Committee that quality more than price should

be attended to; but if an equally good or better quality can be got

at a much lower price, this is a matter of great importance for all

concerned, and ought not to be overlooked.

“I know the subject from its novelty has many

apparent difficulties; still, they are not insurmountable.

“If Mr Stirling or any of the Committee could spare

time, and could get a gentleman such as Digby Wyatt, or any other

neutral person acquainted with art, to go along with him to the

Continent, and see what has been done and doing in stained glass,

and report, the time and money would be well spent, I think.—I am,

my dear Lord Provost, yours faithfully,

“R. Napier.”

Mr Napier and his son John are each represented by a

window in the south-east corner of the choir of the Cathedral, the

subjects being Simon and Matthias the apostles.

He also took part in the movement for transferring

the University to a more suitable site; and his firm subscribed

£2000 towards the fund for erecting the new buildings at Gilmorehill.

In the midst of multitudinous correspondence Napier

still kept in touch with old friends, such as Duncan and Melvill,

the latter of whom was now a K.C.B. This chapter may therefore be

fittingly closed with a letter showing that the opinion Sir James

had expressed to Cunard in former years as to Napiers capability had

only intensified with years..

East India House, 24th December 1856.

My dear Mr Napier, — Very many thanks for the

memorial so well told and illustrated of that great man Watt.

Were he alive he would designate my friend Robert

Napier as the man who, above all other living men, has given

practical effect to the inventions of Watt, and has passed to the

world the great blessing of steam navigation. I in my conscience

believe that the best vessels afloat are those with which you have

had to do.

Many happy Christmases to you, my dear friend, and to

dear Mrs Napier, and to all your family, to each of whom pray

present our united regards and best wishes. — Ever affectionately

yours, James C. Melvill. |