|

As stated in an earlier chapter, Mr Napier acquired

ground at Shandon in 1833, on which he built a small house, where he

was in the habit of residing during the summer months.

Sunny memories are still called up among the few

survivors who were privileged to enjoy the hospitalities of the

first West Shandon house, memories standing apart from any attaching

to the larger house which took its place. The possession of pictures

and other works of art called for a gallery where they might be

suitably displayed; other additions followed, and the mason was much

in evidence over a period of years. Eventually the first house

disappeared, and the structure presently existing took its place,

the whole, especially the front to the Loch, being one of the

happiest creations of Mr Eochead. The building of West Shandon house

extended over many years, but the great tower erected in 1852

practically fixes the date of the present edifice, and the following

is a copy of the writing deposited under the foundation-stone in the

north-east corner :—

“West Siiandon, 18th February 1852.

“This parchment, along with newspapers and a few

coins, was deposited this day under the Tower of West Shandon House.

Another bottle (containing one specimen of each of

the gold, silver, and copper coins at present in circulation, with

the newspapers and other statistical papers of this date, also a

brass-plate having the names of the family engraved on it) has been

deposited in another part of the building.

“Those bottles, &c., &c., have been deposited by

Robert Napier, Engineer, Glasgow, and feuar of West Shandon, for the

amusement it may be of some future generation, provided that the

means taken to preserve the parchment and paper prove successful.

R. Napier.”

The local stone not being well suited to the style of

architecture, fine white sandstone was brought from Bishopbriggs vid the

Forth and Clyde Canal; and the woodwork of the house, after various

differences with contracting joiners, was completed by men from

Govan shipbuilding yard.

In designing and building the house, special

attention was paid to producing a structure that would give little

trouble in the way of repairs; and to obtain this end expensive

expedients were adopted, which the test of time fully justified.

Mr Napier took the greatest interest in Mr Rochead’s

work, and made so many alterations on the plans that he was said to

have been his own architect.

Reference is made to West Shandon in ‘The English

Gentleman’s House,’ and there is a criticism by Professor Kerr, from

which we quote a few extracts :—

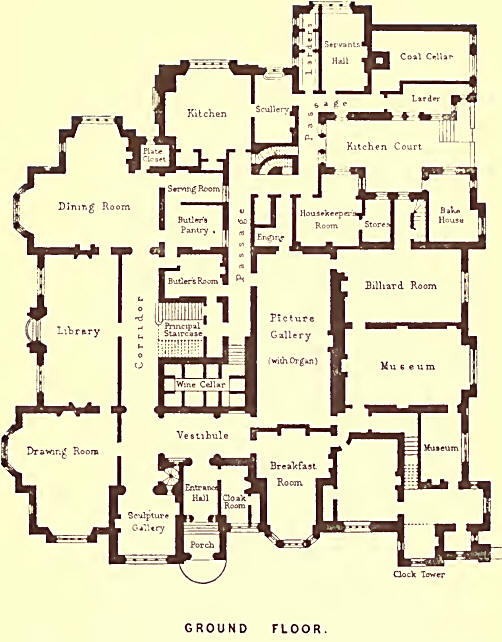

This plan is presented in our series as an extreme

case of intentional irregularity. No doubt there is much of the

merit of convenience obtained by this total want of conventional

regularity. The entrance-hall is much too small, unless we include

with it the interior vestibule, which again, if large enough,

becomes awkward in form. The cloak-room is a good item. . . .

The three public rooms form a good suite of its kind.

The library is very good. . . .

The dining-room must be considered out of rule except

as a sitting-room; the character of form is not that of an

eating-room at all; no doubt considerations of prospect have

governed the case. . . .

The offices generally are very confined, and not

instructive. The same must be said of the museums, picture-gallery,

and billiard-room in their relations to each other and to other

apartments.

To cover over in this way the space which is

generally, in such a plan, an interior court, is not to be

commended; there is too much ceiling light and borrowed light in

consequence, and with these comes stagnation of air and

unwholesomeness, perhaps even on the pleasant shores of the Gareloch

itself.

Mr Napier evidently did not think the criticism

complimentary, so he wrote the author on the subject, and the

Professor replied, saying—

The mediaeval type of arrangement is characterised by

what you quote as “disorderly convenience”: the classical type rests

upon orderly (in too many cases) inconvenience. Between the two, I

prefer the want of order to the want of convenience; and so

evidently do you. As for bad plans, I could have selected them by

the dozen; but a .plan which is not bad, but the contrary, and at

the same time unusually characteristic, was the object of my careful

search, and I thought your house a most striking one in this

respect, and well worthy of study. A passing jest or two in speaking

of it appears to catch the eye of some people, but this is nothing.

I think I may presume that you desire to have an unconventional

unembarrassed house, and your success is complete. That such success

must be paid for by the acceptance of a few drawbacks is but a

truism that one scarcely needs to suggest.

Those who can recall Robert Napier as a capable

business man are now but few, as it is more than forty years since

he personally negotiated a contract; but in his capacity as owner of

West Shandon, making friends of young and old by his geniality, he

lives in the memory of many.

The most attractive part of the house was the museum

and picture-gallery, where was to be found one of the finest amateur

collections in Scotland, of which an elaborate catalogue was

compiled by Mr J. C. Robinson of the South Kensington Museum. There

were many typical examples of the early Italian, Dutch, and Flemish

masters. Raffaelle was represented by a Holy Trinity, which once

formed part of the collection of David, the eminent French painter;

Titian, by a portrait of his daughter; Guido, by a Magdalen from

Lord Chesterfield’s collection; Paul Veronese, Tintoretto, and Da

Vinci, by Scripture subjects. The landscape art of Italy was

illustrated in the works of Pannini, Salvator Rosa, and other

well-known artists. There were numerous examples from the brush of

Rembrandt, Rubens, and Vandyck, and some of the masterpieces of

Quentin Matsys and Teniers, such as the Rent-Day, the Card-Players,

&c. There were also specimens of the art of Verboeck-hoven, Van

Schendel, Cuyp, Jan Steen, Haghe, and other Dutch painters.

Pictures by Claude, Greuze, and Murillo adorned the

walls ; and the school of British art was represented by Reynolds,

Wilkie, Raeburn, and contemporary artists.

In the museum were to be found inlaid ecritoirs,

marqueterie bureaus, buhl cabinets, screens covered with Gobelins

tapestry, and many fine pieces of decorative furniture.

Valuable selections of Dresden, Vienna, and other

European porcelain found a home in cases set around the rooms.

Naturally the French art of the eighteenth century

was well represented, the Sevres porcelain specimens being of

special interest, and including parts of sets of which the other

pieces were scattered over Europe. Five pieces of great beauty

belonged to a set of which the remainder was the property of her

late Majesty Queen Victoria, and these formed one of his special

treasures.

The collection of miniatures, snuff-boxes,

bijouterie, clocks, and watches was most extensive and unique, and

the whole was set out exquisitely.

His taste for ornamental smith-work, as became a

descendant of Tubal-Cain, was displayed in curious old locks and

keys, metal-work, guns, swords, armour, and accoutrements of all

kinds.

Numerous pieces of sculpture by Fillans and others

stood in prominent positions in the hall and elsewhere, but special

attention was always directed to a statue of a veiled lady executed

by the famous Thorwaldsen.

The gathering together of so . tine a collection of

articles of vertu, though a task of no small difficulty, was a

source of the greatest pleasure to their owner. He was justly proud

of it, and at all times he was delighted to show the house and its

treasures to his friends. The majority of his visitors had no

special knowledge of art, but all, even the children, had beauties

pointed out to them, and went away with memories that did not easily

fade.

The grounds, which were laid out with great artistic

taste, were a distinguishing feature of West Shandon. The winter

climate on the Gareloch permits the growth of various foreign trees

and shrubs too tender to succeed elsewhere, and conifers and

rhododendrons were freely planted, whereby beauty was conferred upon

the spot as noticeable in winter as in summer.

Mr Napier’s hospitality was boundless, and is well

illustrated by his offer to place his establishment at the disposal

of Lord Dalhousie, Governor of India, who happened to be staying in

a hotel at Arrochar. To this offer the Marquis replied as follows :—

Arrochar, September 15, 1856.

Sir,—I am unable to thank you sufficiently for your

most kind and courteous letter. Its kindness is so spontaneous and

so manifestly genuine, that I should accept your proposed

hospitality with the greatest pleasure were it not that my movements

are necessarily so uncertain that I should not be justified in

putting you to the inconvenience which my acceptance of your

proposal would inflict upon you.

I trust, however, that you will so far permit me to

profit by your courtesy, as to consider your letter the commencement

of a personal acquaintance with you, and that you will allow me,

when I shall have put away—if ever I do put away— my crutches, to

take some opportunity of presenting myself to you, and of personally

thanking you and Mrs Napier for the very gratifying instance you

have afforded me of real Scottish hospitality. —I beg to remain, my

dear Sir, with many thanks, your very faithful servant,

Dalhousie.

R. Napier, Esq.

As bearing on this subject, we may subjoin a

characteristic letter from his intimate friend Mr Lorne Campbell,

who was factor to the Duke of Argyle, and resided at Poil-na-kill.

Rosneath, Thursday.

My dear Eobert Napier,—Of course you know we have

Lord John Russell here, and you will be glad to know they have seen

the Loch on Tuesday afternoon for the first time in the perfection

of beauty. Among the first objects that attracted his quick eye was

your chateau: and on my telling him whose it was, and what a

terrible fellow you are, he launched forth at once on the Duke, the Cunarders, and

all you have done for them, and said he would like to go and see you

some time while they were here.

They go to-morrow to Lord Minto’s for a few days. He

will likely tell me when he proposes to see you; and I will be sure

to give you notice, that you may be at home.

They are most agreeable, easy people; so when

they do go, don’t make too great an ado about them. A glass of

sherry will serve them ; and if I act as their coxswain, you can, if

you like, give me a glass of champagne.—Yours very truly, Lorne

Campbell.

Not only to private individuals but also to public

bodies lie extended a hearty welcome; and lie took a prominent part

in entertaining the British Association when they visited Glasgow in

1855.

Professor Pillans, writing him at that time, says :—

As one of those who availed themselves of your

kindness in placing the Vulcan steamer at the disposal of the

British Association, I am deputed by them to convey to you, in their

name and, I think I may venture to add, in the name of all the

members of the Association now assembled here from every part of the

United Kingdom, the expression of their cordial thanks and sense of

obligation for the opportunity you afforded them in the “land of the

mountain and the flood” of renewing old friendships and forming new

acquaintances which to some may prove an era in their lives, and to

all will be a day of agreeable recollections.

They regard this act of considerate liberality on

your part as one of a series which promises ere long to extend a

designation, hitherto reserved for the East India Company, to the

yearly increasing number of the “Merchant Princes” of Glasgow.

While entertaining so freely, Mr Napier never forgot

that he had also responsibilities; and social needs came in for a

full share of his bounty. He took a great interest in the church at

Row, which he attended regularly. He was on very friendly terms with

the Argyll family, and in connection with the rebuilding of the

church the Dowager Duchess thus wrote him :—

St Leonards-on-the-Sea,

28th Jan. 1850.

Dear Sir,—I should have replied to your letter, dated

the 12th, much sooner, but my health is often my excuse for

deferring letter-writing, and I shall therefore hope you will excuse

my delay.

I have asked Mr Davidson to address you on the

subject of the Row church, &c., &c. He manages for me all these

matters, as I am myself quite unfit to do so.

I am sure the parish generally are much indebted to

you for the great interest and liberality with which you deal with

them.

I trust all will be well and pleasantly arranged

regarding the new church to please all parties, and to be conducive

above all things to the comfort of our worthy minister.

I hope Mrs Napier and the other members of your

family are quite well.

With kindest remembrances to Mrs Napier and yourself,

I am, dear Sir, yours very sincerely,

A. Argyll.

Robert Napier, Esq.

of West Shandon.

The Rev. Laurie Fogo, who succeeded the saintly John

Macleod Campbell, was minister of Row parish, and during his

incumbency the present handsome church was built. To its erection Mr

Napier contributed liberally, and lie also placed in the churchyard

an elaborate monument, in the form of a statue, to mark the

resting-place of Mr Henry Bell, the pioneer of steam navigation. |