|

We now come to one of the most important events in

Napier’s career — the founding of the celebrated Cunard Company. In

the inception of this enterprise the leading role was taken by him,

and we purpose going into this matter somewhat fully in the light of

the documentary evidence still extant.

In the early ’Thirties, about the time Robert Napier

was expressing his opinions on the practicability of regular steam communication between the two continents, the same

subject was being considered from a different point of view by a

prominent Canadian, Mr Samuel Cunard, whose attention was directed

to the matter by the successful trans-Atlantic passage made by the

small Quebec-built steamer Royal William already referred to. Cunard

was descended from a family of Pilgrim Fathers who had emigrated to

America in the early part of the seventeenth century and settled

in Philadelphia. When the United States declared their independence,

the Cunard family was loyal to its British traditions, and removed

to Halifax, where Samuel was born in 1788.

After serving an apprenticeship in a merchant's

office he obtained a partnership in a Boston shipping firm, which

conducted a service between Halifax and England, employing on the

trade “tublike” vessels widely known as “coffins,” from the fact

that several of them foundered in the stormy waves of the Atlantic.

The good passages made in the beginning of 1838 by

the Sirius and Great Western, and the efforts that were being put

forth by the British and American Steam Navigation Company to

establish regular communication, stimulated Cunard to endeavour to

make his dream of an Atlantic postal service a reality. He was not

unknown to the Admiralty, as he had already conducted a mail service

between Newfoundland and Bermuda in a manner that satisfied the

British Government.

In the end of 1838 he obtained a provisional Atlantic

mail contract, and set out for England to take the necessary steps

for fulfilling it.

Cunard was agent in Halifax for the East India

Company, and on his arrival in London he consulted the secretary of

the Company, Mr James C. Melvill, regarding the building of steamers

for the proposed service. Mr Melvill was on intimate terms with

Robert Napier, who had supplied his Company with the Berenice and

other vessels, and he strongly advised Cunard to put himself in

Napier’s hands.

Accordingly, on 25th February 1839, we find that

Cunard formally opened negotiations through his agents, Messrs

William Kidston & Sons, of Glasgow, writing to them as follows :—

Piccadilly, 25th February 1839.

Dear Sirs,—I shall require one or two steamboats of

300 horse-power and about 800 tons. I am told that Messrs Wood

& Napier are highly respectable builders, and likely to be enabled

to fulfil any engagement they may enter into. Will you be so good as

to ask them the probable sum for which they would engage to furnish

me with these boats in all respects ready for sea in twelve months

from this time? I am told that the London is a fine vessel, and

about the description of vessel that I might require; but I have not

seen her. I shall want these vessels to be of the very best

description, and to pass a thorough inspection and examination of

the Admiralty. I want a plain and comfortable boat, not the least

unnecessary expense for show. I prefer plain work in the cabin, and

it will save a large amount in the cost. If I find these gentlemen

are likely to meet my wishes, I will immediately proceed to Glasgow

and make the necessary arrangements with them. I shall also require

two or three boats of 150 horse-power: perhaps they will say the

probable cost of a boat of this latter size, complete for sea, with

a plain cabin, &c., &c. S. Cunard,

At the General Mining Association, Ludgate Hill.

Messrs W. Kidston & Sons.

Possibly Cunard may have been acquainted with the

nature of Napier’s proposals for Atlantic steamers; at any rate, it

is to be noted that the size and power of the boats he mentions are

exactly those fixed on by Napier in his letter, written in 1833, to

Mr Patrick Wallace as the minimum he would recommend.

To Messrs Kidston’s inquiry Napier replied at once :—

“Vulcan Foundry, 28th February 1839.

“Gentlemen,—In reply to your inquiry as to whether it

is my practice to contract and supply companies with steam-vessels

finished and completed ready for sea, and whether I am at present in

a position to undertake the construction and delivery of two or more

vessels so as to have them ready in twelve months from this date,

and the cost of steam-vessels about 800 tons and 300 horse-power, it

has been for many years past my practice to contract with companies

to supply them with steam-vessels ready for sea.

“In this way I supplied the Dundee Shipping Company

(George Duncan, Esq., Chairman) with three steam-vessels — the

Dundee, Perth, and London; the Inverness Shipping Company (Thomas

Davidson, Esq., Findhorn, Manager) with the Duchess of

Sutherland; the Aberdeen & Leith Shipping Company (Robert Mitchell,

Esq., Manager) with two vessels, the Sovereign and Duke of

Richmond; the East India Company (James Melvill, Esq., Secretary)

with one vessel, the Berenice ; the Isle of Man Steam-Packet Company

with three vessels; the Londonderry Steam-Packet Company with three;

the Belfast Company, Glasgow, with three; the City of Glasgow

Steam-Packet Company with the John Wood, Vulcan, City of

Glasgow, and a new vessel at present building for them. I also

supplied Thomas Assheton Smith, Esq., with three vessels—the Menai,

Glow-worm, and Fire King. To any of these parties you are at full

liberty to apply in order to ascertain the manner I fulfilled my

contracts for these vessels.

“From the great accommodation I have for doing work,

I could at present undertake to build and finish in twelve months

two or more steam-vessels, were I favoured with the order soon. The

cost of these vessels depends on so many different things that it is

hardly possible to name a price for them without knowing more about

them than you have communicated to me. I have done them as low as

£35 per ton of total measurement of the vessel, and I have got above

£50 per ton for some others. I may, however, state that good

vessels, warranted to stand any inspection and give entire

satisfaction both as to the vessel and machinery, cannot be done for

less than from £40 to £42 per ton,—this for the vessel ready for

sea, with cabins, sails, rigging, anchors, cables, &c.

“If your friend is really in want of vessels I shall

be happy to go to London and meet him, and I have no doubt but that

we would in a very short time understand one another.—Your most

obedient servant, R. Napier.

“Messrs W. Kidston & Sons.”

Cunard, on receipt of this letter, thought his best

course was to go to Glasgow to see Napier with the intention of

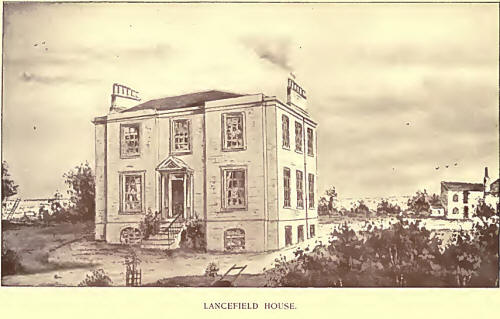

arranging the contract; and accordingly early in March a meeting

took place at Lance-field House. What then transpired can be best

told in Napier’s own words, in a letter written on 28th January 1841

to Messrs J. & G. Burns, as Messrs Burns’ firm was then styled.

“As there are some things connected with these

vessels that may not be known to you and the other owners so well as

to the Honourable S. Cunard and myself, I hope you will excuse me

making a few explanations — viz. : The first application that was

made to me about these vessels was through Messrs William Kidston

& Sons, and on the 28th February 1839 I wrote them a letter for the

information of Mr Cunard, and stated that vessels warranted to stand

inspection cannot be done for less than £40 to £42 per ton. Some

short time after this Mr Cunard came to Glasgow and waited upon me

at my house with specifications, &c., for vessels of 800 tons and

300 horse-power, for which he wished an offer from me, to be

finished in a plain substantial manner; and seeing that he was

prepared at once to give me an order if my terms pleased him, I at

once said at the rate of £40 per ton. His reply was that he

considered it fair and reasonable, but as he had three vessels all

of one size (and that similar to what I had in hands for the City of

Glasgow Steam-Packet Company), he said if I took £30,000 for each of

the vessels, he would give me the order before he left me. This I

agreed to as per the missive letter sent you, accepted and signed by

Mr Cunard.”

This was the first arrangement for the Halifax

steamers, and it will be observed that it was completed at the first

meeting that took place between Mr Cunard and Napier.

Business requiring his attention in London, Mr Cunard

at once went south, leaving instructions to get copies of plans and

specifications ready for his approval. He returned to Glasgow for

this purpose about the 12th March. During his absence, however,

Napier had been reflecting on the whole problem, and had come to the

conclusion that unless the vessels were made larger they would not

be successful. He urged Cunard very strongly to increase the

dimensions, but he was most reluctant to give his consent, as the

expense alarmed him. Napier, on the other hand, dreaded failure ;

and the course he adopted to avert this can best be told in his own

words, taken from the letter we have already-quoted.

“I said to Mr Cunard that if he paid for the

alteration of the vessel and work connected therewith, which I

thought, if properly gone about, might be done for the above sum

(£2000), that I would then make him a present of all my part of the

work for the enlarged size of vessels. He at once saw the great

benefit to be derived to him from this arrangement, and accordingly

the contract of 18th March 1839 was drawn out.”

This contract stipulated for steamers of 960 tons,

with engines of 375 N.H.P., and the price was fixed at £32,000 for

each vessel.

The second arrangement was not such a favourable one

for the engineer as the first one. Napier, however, was always very

jealous of his reputation, and was prepared to make sacrifices to

maintain it, and hence his proposal to Cunard. To quote his own

words, “ He felt that if these small vessels did not succeed they

would do him more injury in character than any money he could gain

would benefit him.” A formal contract was now entered into and

signed on the 18th March 1839, the sole contracting parties being

Samuel Cunard and Robert Napier. The same day Cunard left for

London, and the first stage of the negotiations was reached. Napier

next day wrote a letter of thanks to his friend Melvill.

“Glasgow, 19£A March 1839.

“My dear Sir,—Yesterday, after signing the contract

in a formal manner, Mr Cunard left this per mail for London.

“It being customary in our Scotch contracts to name

arbiters to settle any differences that may arise between the

contracting parties, I took the liberty of naming you to Mr Cunard.

To this he agreed at once.

“I hope you will excuse this liberty on the faith you

are not to be troubled further than coming down, I trust, and taking

a sail up in one of the vessels to London.

“I am of opinion Mr Cunard has got a good contract,

and that he will make a good thing of it. From the frank offhand

manner in which he contracted with me, I have given him the vessels

cheap, and I am certain they will be good and very strong ships.

“I can only again repeat my obligations to you for

your kindness, and am, dear Sir, yours faithfully, R. Napier.

“James C. Melvill, Esq.,

Secretary, The Honourable East India Company.”

When Cunard arrived in London he at once put himself

in communication with the Government, and informed them what he had

arranged. On the 21st March he wrote to Napier—

The Admiralty and Treasury are highly pleased with

the size of the boats. I have given credit where it is due to you

and Mr Wood. I have pledged myself that they shall be the finest and

best boats ever built in this country.

You have no idea of the prejudice of some of our

English builders. I have had several offers from Liverpool and this

place; and when I have replied that I have contracted in Scotland

they invariably say, “ You will neither have substantial work nor

completed in time.” The Admiralty agree with me in opinion that the

boats will be as good as if built in this country, and I have

assured them you will keep to time.

Again on the 25th March he wrote :—

Am I not right in saying you are to give me

everything upon the best and most improved plan.

On 27th March Napier replied to Cunard :—

“I am in receipt of your esteemed letters of 21st and

25th current. I was quite prepared for your being beset with all the

schemers of every description in the country and in this stage of

the business, and think it right to state that I cannot and will not

admit of anything being done or introduced into these engines but

what I am satisfied with is sound and good. In a word, I shall not

pay the least attention to any scheme but that I have fixed

on—viz., ‘your engines will be made similar in construction to those

I am at present making to the Admiralty.’

“Hall’s condensers cannot be allowed if it was on no

other ground but that of time, as it would be actually impossible

for me to meet your time and adopt his plan. Every solid and known

improvement that I am made acquainted with shall be adopted by me,

but no patent plans.

“I am sorry that some of the English tradesmen should

indulge in speaking ill of their competitors in Scotland. I shall

not follow their example, having hitherto made it my practice to let

deeds, and not words, prove who is right or wrong. At present I

shall not say more than court comparison of my work with any other

in the kingdom, only let it be done by honest and competent men.”

Now at this time the British Queen was being finished

by Napier. This vessel, and her sister ship the President^ were very

much larger and finer steamers than those Mr Cunard had ordered; and

in view of this fact and the letters he was receiving from his

customer, Napier suggested the desirability of still further

increasing the vessels. To this proposal Cunard turned a deaf ear,

as he was unwilling to incur further expense, more especially as the

Admiralty and Treasury had expressed themselves satisfied.

Mentioning the matter to Mr Melvill, and recounting

his Glasgow experience, Cunard stated incidentally that the

Admiralty were pleased with the ships, but that Napier considered

them still too small, and was always proposing larger boats. Mr

Melvill expressed the opinion that to ensure success the adoption of

Napier’s views was imperative, as he was the great authority on

steam navigation, and knew much more about the subject than the

Admiralty.

Cunard rejoined that while he valued Napier’s advice,

larger boats meant more money, which he could not afford, as he had

been disappointed in getting his stock taken up ; and even the offer

of the agency to his correspondents, Messrs Kidston, had not induced

them to participate in his enterprise.

Melvill strongly advised him to go north again and

place the matter fully before Napier, as he thought he would be able

to assist him in his difficulties, and Cunard at once adopted this

suggestion.

Another meeting took place at Lance-field House, at

which Mr Cunard explained the position, and Napier, after

consideration, said he thought he could help him in his difficulty.

As already mentioned, he was one of the founders of

the City of Glasgow Steam-Packet Company, whose steamers plied to

Liverpool. The Company was managed in Glasgow by Messrs Thomson

& Mac-Connell, and in Liverpool by Napier’s friend Mr David Maclver.

Thinking that those interested in local shipping

would risk something in an ocean venture, he sounded his friends and

other co-shareholders, including Mr James Donaldson, a wealthy

cotton broker. They responded enthusiastically, Donaldson personally

undertaking to subscribe £16,000.

Having succeeded so far, he now approached Mr George

Burns, who had fallen heir to the Belfast trade which the Napiers

originated, and who, along with Mr Martin, was agent for a line of

steamers trading to Liverpool.

Napier knew Mr Burns as an excellent business man and

capable agent, and he suggested that he mio;ht obtain for him the

agency of Cunard’s steamers if he could assist in raising a part of

the capital.

Burns, after due consideration, fell in with the

proposal, and as prospective agent he propounded the scheme to

Napier’s friends and his own shareholders.

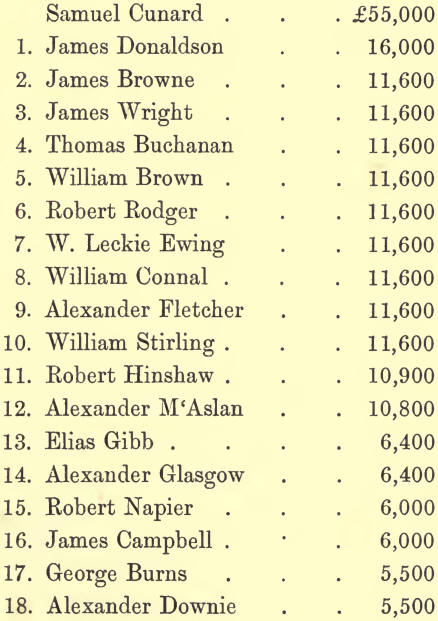

As stated in the life of Sir George Burns, the amount

aimed at (£270,000) was at once subscribed, and the new copartnery

was called the British & North American Royal Mail Steam-Packet

Company.

The original subscribers were as under:—

It will be observed Mr Cunard had by far the largest

holding in the Company, and the other shares were divided pretty

equally between Mr Napier and his friends and Mr Burns and those

whom he induced to join the enterprise. Though Mr Burns personally

did not subscribe a great amount, he obtained through

Mr Napier the agency, which was by far the most

lucrative position in the venture. Napier, however, recommended

Burns not for his wealth, but for his commercial ability, and the

future history of the Company justified his selection.

The management of the steamers, including the

appointment of officers and crew, was entrusted to Napier's old

friends, Messrs Maclver of Liverpool, who performed their part in

the most efficient manner.

The newly constituted Company adopted Mr Cunard’s

contract as a basis. The number of the vessels was increased to

four, and they were made larger and more efficient in the way Napier

desired ; in fact, everything was left to him, and his mark is still

to be seen in the red funnel, which had hitherto distinguished the

steamers he was interested in.

In addition to increasing the dimensions, the ships

were filled up solid in the bows between the timbers with strong

beams and knees, and water-tight bulkheads were fitted to prevent

accident should the vessels strike ice. They also were doubled all

over with hardwood planks, and strong iron straps were fitted to

prevent straining. The cabin accommodation was made much more

luxurious than originally contemplated, and perhaps this was

necessary, as the fare was 38 guineas.

The names of the four vessels

werethe Acadia, Britannia, Caledonia, and Columbia, — the Acadia,

built by Wood, being the “pattern card.” The first to sail was

the Britannia, commanded by Captain Woodruff, which started from

Liverpool on 4th July 1840, and arrived in Boston a fortnight later.

On her outward passage she was retarded by westerly winds, but

sailing' for home in the ensuing month, she made the return voyage

in a little over ten days, her best day’s steaming being 280 knots.

Such was the part played by Napier at the start of

this celebrated Company; and from the preceding narrative it will be

apparent that it was mainly through his co - operation with Mr

Cunard, first in enabling the latter to get his plans into practical

shape, and then in providing a series of steamships unrivalled in

their time, that immediate success was attained.

It was the confidence reposed in Robert Napier, in

the man and in his work, that secured most of the capital necessary

(outside of Mr Cunard’s contribution) to found the Company on an

adequate basis, and it was undoubtedly the excellence and uniform

success of the machinery and vessels he supplied that gained for the

British and North American Company that support from the commercial

world which led to its remarkable prosperity, and enabled it to

emerge triumphant from its memorable contest with the Collins Line.

“Napier was the practical head and hand of the Cunard

Company in its early days, without which it might have proved a less

successful venture in the vast field of enterprise it so long

monopolised.”

By those possessed of the requisite knowledge, Mr

Napier’s energy, organising skill, and engineering ability have been

cordially recognised as the foundation from which the Cunard Company

took its beginning, but by no one was the importance of his services

acknowledged with greater freedom than by Mr Cunard himself. Between

Cunard and Napier there existed a lifelong friendship. At the

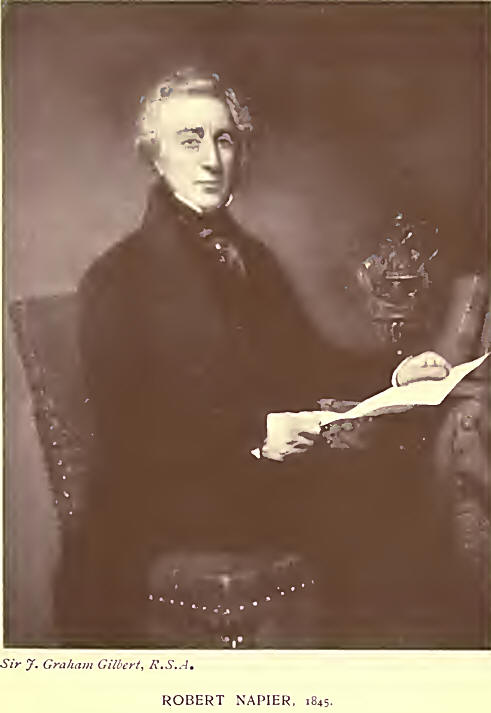

latter’s request he sat for his portrait, which was presented to his

daughter, Miss Cunard, with whose letter of thanks as reflecting

these sentiments we conclude.

Bush Hill, Edmonton, Jan. 17,1860. My dear Sir,—The

portrait of my father that you have been so very kind as to present

to me

has now been hung up in the dining-room at Bush Hill,

and, although personally a stranger to you, I hope you will allow me

to express my sincere thanks for a gift that must be valuable to me

for its own sake, as well as for the sake of the donor, whose name

has been familiar to me from early childhood in connection with much

that I have heard of science and natural energy and talent.

Your present will always silently remind me of your

generosity, which will at all times be remembered with pleasant

gratitude.—Believe me, my dear Sir, yours truly and obliged,

Elizabeth Cunard.

R. Napier, Esq. |