|

It is now incumbent on us to show the part that

Robert Napier took in the inception of Atlantic steam navigation.

Hitherto what he had undertaken to do had been successfully

accomplished, and his work had been characterised by great

thoroughness; but at the same time it must be remembered that nearly

all the vessels had been built for short - distance runs in

comparatively quiet waters.

When he undertook the contract for the Dundee boats

he said he had a purpose in view, and there can be little doubt that

this object was to build an Atlantic steamer.

Between Britain and America there' was at this time a

regular and increasing trade conducted by sailing-packets.

In 1819 the Savannah, a small sailing-ship of 350

tons, with auxiliary paddles, came across from America to this

country partly under steam, but chiefly under sail. Her performance,

however, was considered so unsatisfactory that her engines were

taken out in the following year, and up to the end of 1832 no

further attempt was made to cross by steam.

In August 1833 the Royal William steamed over from

Quebec, but prior to this date the subject of trans-Atlantic

navigation had been fully dealt with by Napier.

In the beginning of 1833 he was consulted by Mr

Patrick Wallace of London regarding a regular service of

steam-vessels betwixt Liverpool and New York, and his reply, dated

3rd April of that year, is subjoined. The letter is a long one, but

we reproduce it in its entirety as showing how carefully Napier had

studied the problem in all its bearings, and what a clear conception

he had of the whole situation, of the requirements of the trade, and

the size, speed, and strength of the vessels necessary for success.

This forecast is all the more remarkable, as he had nothing to guide

him, and the opinions of professed experts such as Dr Dionysius

Lardner were not encouraging.

“Vulcan Foundry, Glasgow, 3rd April 1833.

“Dear Sir,—I am sorry that it has been out of my

power to write you sooner. I now send you my opinion, with some

remarks about the proposed speculation for establishing

steam-vessels betwixt Liverpool and New York, with an estimate of

the probable cost of fitting out and sailing these vessels. Before

going into details,

I may mention that I have endeavoured to state

everything as fairly and candidly as possible, so as not to mislead

you or your friends, and have rather overestimated the cost and

expense than otherwise. The amount of revenue, I am aware, can only

be an approximation to the truth, for in all new undertakings of any

magnitude many things occur that cannot be foreseen; but judging

from what has taken place in other stations where steam-vessels have

been introduced, it is reasonable to calculate upon a very great

increase of revenue in a short time. But in an undertaking of such

magnitude as the one proposed, it is of the greatest importance that

the whole be reviewed in a broad and liberal manner at the outset,

and everything that can be brought to bear either for or against the

interest of the speculation, fairly weighed and balanced before

anything is decided upon. If your friends are in earnest about

entering upon the speculation, they should make up their minds to

meet with strong opposition and other difficulties for a short time.

But if they enter upon it with a determination to meet opposition

and difficulties spiritedly, and to overcome them, then I have not

the smallest doubt upon my own mind but that in a very short time it

will be one of the best and most lucrative businesses in the

country, provided always that the Company set out right at first by

having first-class vessels fully suited for the trade in every

department. I am aware that in getting up the first of these vessels

great care and attention will be necessary to gain the different

objects in view, and in doing this an extra expense may be incurred,

but which may be avoided in all the other vessels. If the practical

difficulties, &c., are fairly surmounted in the first vessels,—and

which I have no doubt but they may,—the first cost and sailing

expenses of the two first vessels ought not so much to be taken into

account. In fact, I consider it as nothing compared with having them

so efficient as to set all opposition at defiance, and to give

entire confidence to the public in all their arrangements and

appointments, cost what it may at first; for upon this depends

entirely the success, nay, the very existence, of the Company.

“I wish it therefore to be impressed upon the minds

of your friends the great necessity of using every precaution that

can be thought of to guard against accidents on such a long passage,

and if accidents should happen, to be prepared with a remedy to meet

any common one that may occur, as far as possible. By attending to

this you will give confidence to the public and comfort to

yourselves, and in the end I am certain it will more than repay you.

“The plan I would propose with regard to the whole of

the engineer department is: I would endeavour to get a very

respectable man, and one thoroughly conversant with his business as

an engineer; I would appoint this man to be master engineer, his

duty to superintend and direct all the men and operations about the

engines and boilers, &c., to be accountable to the captain for his

conduct—viz., to be under the captain. All the other men for working

the engines should be regular bred tradesmen, and all the firemen

boiler-makers. A workshop, with a complete set of tools and

duplicates of all the parts of the engines that are most likely to

go wrong, should be on board. In a word, I would have everything

connected with the machinery very strong and of the best materials,

it being of the utmost importance to give confidence at first, for

should the slightest accident happen so as to prevent the vessel

making her passage by steam, it would be magnified by the

opposition, and thus, for a time at least, mar the progress of the

Company. But if, on the other hand, the steam-vessels are successful

in making a few quick trips at first, and beating the sailing

vessels very decidedly, then you may consider the battle won and the

field your own.

“With regard to the size of the vessels, I am

decidedly of opinion they should not be less than 800 tons,—probably

more,— and propelled by two engines of not less than 150 horse-power

each, or 300 in whole, so as to ensure good passages in almost any

kind of weather. The model of the vessels should be such as is best

adapted for great speed, and carrying a large cargo on a moderate

draught of water ; but upon no account should the model be

sacrificed for the sake of cargo, for the future success of the

Company depends in having fastsailing steamers as well as good ones.

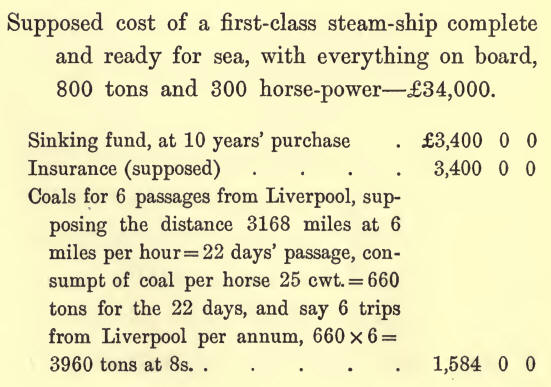

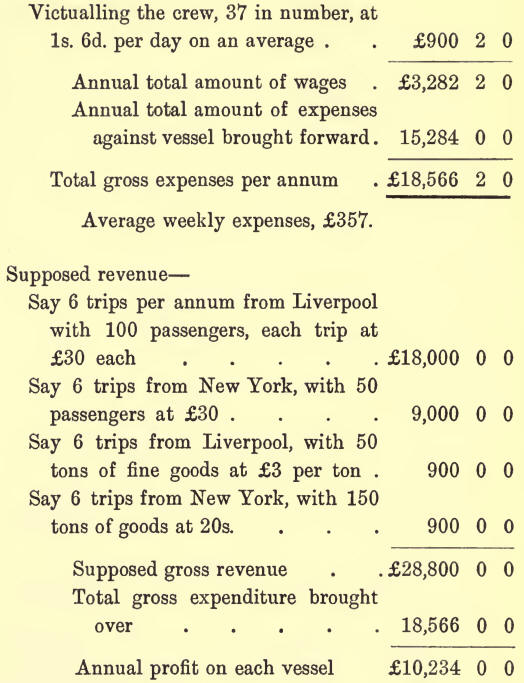

“In the estimate I have made of the probable cost of

such vessels as will suit your purpose, I have thought it prudent to

make a considerable allowance for extras to the two first

vessels—viz., I have considered the vessels completely ready for

sea, with everything on board necessary for the vessel and

machinery—viz., sails, rigging, anchors, cables, cabin furniture

complete, engines and machinery duplicates, tools, iron tanks for

coals, and water to trim the vessel. In a word, everything complete

for the passage.

“From an official document I have, I find that the

number of passengers that have left the Clyde for two years is as

under:

For New York—

In the year 1831, 1336 passengers; and In the year

1832, 1672 passengers.

For the British Colonies in N. America—

In the year 1831, 3062 passengers;

In the year 1832, 3273 passengers.

To the above may be added all that leave this country

for debt, &c. From the North of Ireland—viz., Belfast and

Londonderry —a very great number of passengers go annually to the

States and Colonies. A great proportion of them could not afford to

go by steam; still there would be a number that would go.

“I have mislaid the document I had for the average

number of passengers that regularly sail from Liverpool every week.

I am, however, in daily expectation of a correct list of the number

of the ships, which, if I think of any use to you, I will send it.

You no doubt are aware that the best time for passengers is the

spring and fall of the year. One of the Packet's ships last fall had

£1800 of passage-money from New York. The two last ships that sailed

from Liverpool had about £1000 each of passage - money. Cabin fare,

35 guineas to New York and 30 to Liverpool; fine goods, Is. per

foot. A Packet ship leaves Liverpool every week. Besides the regular

Packet ships, about 170 vessels averaging 400 tons each have left

Liverpool for New York from the 1st March 1832 to the 1st March

1833, and in the same time about 90 vessels about the same burden

have left Liverpool for New Orleans, making a total of 260 ships

from Liverpool, which all carry more or less passengers, a number of

whom I have no doubt would go by steam were it once fairly

established.

“From all I can

judge, I am convinced the number of passengers that are likely to go

regularly are rather under than over stated, but I expect to be able

in a few days to form a more correct estimate of the whole.

“I hope you will excuse me putting you to so much

postage, but really I have not time to write you a short letter.

“I shall be glad to hear from you, and am, dear Sir,

yours very truly,

“Robert Napier.

“To Patrick Wallace, Esq.,

London.”

No business resulted with Mr Wallace and his friends,

and the project fell through from lack of funds.

A proposal was made to Mr Napier that he should put

his ideas into practice and build a large steamer on speculation;

but while he gave the matter consideration he came to the conclusion

that the risk attending such a venture would be too great. His view

was that the hull should be about 220 feet long, with 40 feet beam;

and he estimated the cost of such a vessel with large engines to be

about £50 per ton. It may be noted that these dimensions were

approached in the Great Western (the first vessel to cross without

re-coaling), and exceeded in the case of the British Queen, which

measured 245 feet long by 40 feet beam.

An opportunity soon thereafter afforded itself of

showing what he could do on the Atlantic. In 1836 the British and

American Steam Navigation Company was formed, with a capital of

£1,000,000 sterling. Mr Macgregor Laird, with whom Napier was

intimate, took a prominent part in the formation of this Company,

and was appointed secretary. The Company resolved to order a large

steamer, and Mr Laird entered into negotiations with Napier, who

offered to supply the engines, which were of unusual size, at £50

per nominal horse-power, and to look after the building of the hull

for a fee of £1000 sterling. Hall’s condensers were thought to be

desirable ; but at first Napier was not willing to supply them, as

his limited experience with such condensers had cast a doubt in his

mind on their reliability, and he was against introducing a novelty

in a large pair of engines.

In October he made a definite offer to supply the

machinery with Hall's condensers for £20,000 sterling, but his

tender was not accepted, and the order was placed with Messrs Claude

Girdwood & Co. This firm, however, was not able to implement the

contract, and about a year later Napier was asked to undertake the

work, which he did at a price considerably above his original offer.

The engines were much larger than any he had hitherto

made, the cylinders being 77½ inches and the stroke 7 feet. The hull

of the vessel was built by Messrs Curling & Young of London, but

Napier took care to give the builders special directions as to the

strength and fastening of the engine keelsons, paddle-beams, &c., so

that his machinery should be rigid; and it was said that whatever

else might break up, the part connected with the engines would stick

together,—a fact which was brought home to the ultimate purchasers

of the vessel when they dismantled her.

The British Queen, which cost £60,000 sterling, was a

magnificent steamer, and much larger than the early Cunard boats.

There was a very bitter feeling raised that such a fine vessel built

on the Thames should be engined in Scotland, and an acrimonious

correspondence on the subject was carried on for a long time in the

‘Mechanics’ Magazine under the heading

of “London versus Country-made Engines,”—an attempt being made to

decry the Scottish contractor. Napier’s motto was “Deeds, not

Words,” and after the vessel had been running for a year he emerged

triumphant, one of the correspondents writing, “I will only ask

where the engines of the British Queen can be matched, in any

respect whatever, either for strength of material in proportion to

their power, for beauty of design, for smoothness while in motion,

and above all, for the high state of perfection in which the engines

perform their duty?” which challenge was unanswered. Comparison was

instituted between the engines of the British Queen and those of

the Great Western, made by Maudslay, when it transpired that the

framing of the latter had given way and required to be patched with

malleable iron straps.

The speed of the vessel was taken from an average of

the Dundee and Perth boats, and was intended to be a mean of 9 knots

an hour in all weathers, so that she might make the passage from

London to New York in 14 to 15 days. This estimated speed was

accomplished on service with a daily consumption of forty tons of

coal.

She was launched in May 1838, and sent round at once

to the Clyde receive her machinery; but from various causes she did

not make her first voyage till 12th July 1839, sailing on that date

from Spithead with a full complement of goods and passengers. She

made the passage in 151-days, her best day’s steaming being 240

knots.

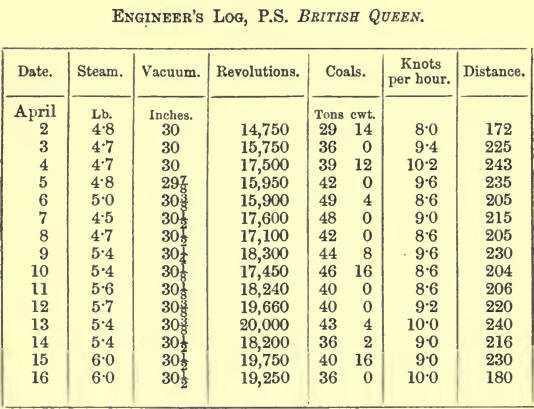

The details of the performance of what was then

considered an Atlantic greyhound, with boilers working at 5 lb.

pressure, are interesting, and we submit an extract from the

engineer’s log, giving particulars of the vessel’s fourth voyage

from New York to London :—

Total number of revolutions from New York to

Portsmouth, 263,400 ; total quantity of coals, 613 tons 16 cwt. Left

New York 1st April 2.30 p.m. ; arrived at Spithead 16th April 1840

at 6p.m.

The British and American Company originally

contemplated building two vessels in America and two in this

country, and they intended to run steamers twice a-month to New

York, starting alternately from London and Liverpool. With this

view they ordered the President and another steamer,

and proposed following with similar large vessels; but the advent of

the subsidised Cunard Line and the loss of the President, which

sailed from New York in 1841 and was never again heard of, caused

the enterprise to end in failure. |