|

It has been previously mentioned that there existed

an intimate connection between Robert and his cousin, David Napier,

from whom he had acquired the Camlachie Foundry. Robert was now

carrying on an extensive business in the Vulcan Works, but finding

them too small to overtake the contracts offered him, he again

approached his cousin in a characteristic letter.

“Whitevale, 7th Nov. 1835, 8 p.m.

“Dear Cousin,—I once heard you say that you would

either let or sell your premises at Lancefield. Are you so disposed

still ? If so, the rent for the whole, or the lowest price for the

whole, and the terms of payment ? At present I could not venture to

withdraw cash from my business to pay you cash, but I would pay

part.—I am, yours sincerely,

“R. Napier.”

David seemed desirous of leaving Glasgow, and the

negotiations thus abruptly entered on were concluded at once, as the

following letter shows :—

Lancefield, 7th Nov. 1835.

Dear Cousin, — I hereby become bound to let to you

for twelve years from Whitsunday next, the whole heritable property

belonging to me at Lancefield for £500 a-year, payable in equal

instalments at Martinmas and Whitsunday, you having a right to

purchase it within the first seven years of the lease on paying

£20,000. If a sale takes place, £5000 to be paid down in cash, and

the remainder in equal instalments, including interest; and during

the other five years of the lease I shall not be at liberty to sell

it without first offering it to you. During the course of the lease

you pay all public burdens.—I am, dear Cousin,

David Napier.

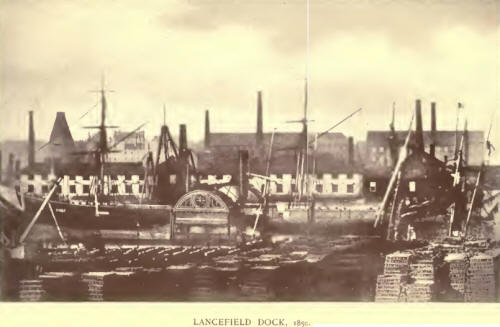

On completion of the agreement, Robert at once

removed his residence from White-vale to Lancefield House, and it

may be noted in passing that he exercised his right of purchase

within the stipulated time, and became proprietor in 1841. The

Lancefield property included a tidal basin; and in after years the

Clyde Trustees, in a very hectoring and bullying manner, endeavoured

to take this away, even threatening force, to which threat Napier

rejoined that he would repel force by force. They then engaged in

litigation, and the upshot of the matter was that Napier succeeded

in thoroughly defeating them, getting a special Act of Parliament,

by. which he remained undisputed master of his dock.

In the closing years of his life it was purchased by

the Trustees at a very large price. In fact, he got twice as much

for the dock as he paid for the whole Lance-field property.

About this time he entered into a new agreement with

his manager, Mr Elder, for a period of seven years. His salary was

to be £250 per annum, and 7s. 6d. for each Nominal Horse-Power his

employer contracted for, which bonus came to a large sum. There was

an unusual clause introduced into the contract—viz., that Elder was

to have the right of making plans for his own private use. When this

engagement expired it was renewed for other five years, and Napier,

in an interesting postscript to a letter written in November 184:2

to his friend Mr Moncrieff, says: “You will perceive Mr Elder and I

have arranged, in the spirit of true friendship, for another lease

of each other’s services for five years, if we are spared together

so long. If all is right with both of us, it should nearly, I think,

terminate the laborious and active part of our lives.” His

prognostications, however, were so far from being fulfilled that he

continued actively engaged in business for nearly thirty-five years

after this date.

In those days it was customary to have engagements

extending over a period of years with leading hands and foremen.

Thus in 1828 Mr Napier had brought James Thomson from Manchester to

act as leading smith, finisher, and turner for a period of years. He

was to receive the sum of £10 to defray the expense of conveying his

family from Manchester to Glasgow, and a wage of 36s. per week, to

be paid fortnightly; and a formal stamped document was drawn out

embodying this agreement. A new engagement was entered into on 8th

June 1838, reading thus :—

It is hereby agreed between James Thomson and Robert

Napier that the said James Thomson shall give the whole of his

personal services for the term of five years from and after this

date. On the other hand, Robert Napier to pay the said James Thomson

a yearly salary of £120 sterling, with a bonus of £5 for every pair

of engines that are finished and set agoing from the Works of Vulcan

and Lancefield Foundries, commencing with the following engines:

The Victorias, Fire King's, Glow-worm’s, Aberdeen and Arran

Company’s engines; these bonuses to be paid at the end of each year

for all engines set agoing and finished during the preceding year;

and we agree to put this on stamp paper.

Witness R. Napier.

H James Thomson.

About the same time he engaged George, brother of

James Thomson, as foreman of Lancefield Works on somewhat similar

terms. James Thomson by-and-by acquired some capital, and in 1847 he

left Mr Napier’s employment, and, along with his brother, founded

the firm of Messrs James & George Thomson, known afterwards as the

Clydebank Shipbuilding Company. Messrs Thomson removed their works

from Glasgow to Clydebank about 1870, and the firm has now become

incorporated with the Coal, Steel, and Armour-plate Company of John

Brown & Co., Sheffield and Clydebank.

Although helped by able foremen, many of whom

afterwards struck out for themselves, the business depended largely

on Napier’s own personal exertions; and as he was often called away,

his affairs were very apt to get into confusion. His wife’s cousin,

Mr John M‘Intyre (whose son, Mr James M‘Intyre, one of the founders

of the firm of Napier & M‘Intyre, was also at Vulcan Foundry), had

acted as his factotum for many years. His death, which took place in

1840, left his employer in a dilemma, as he had no person in his

establishment whom in his absence he could absolutely trust with the

management of affairs.

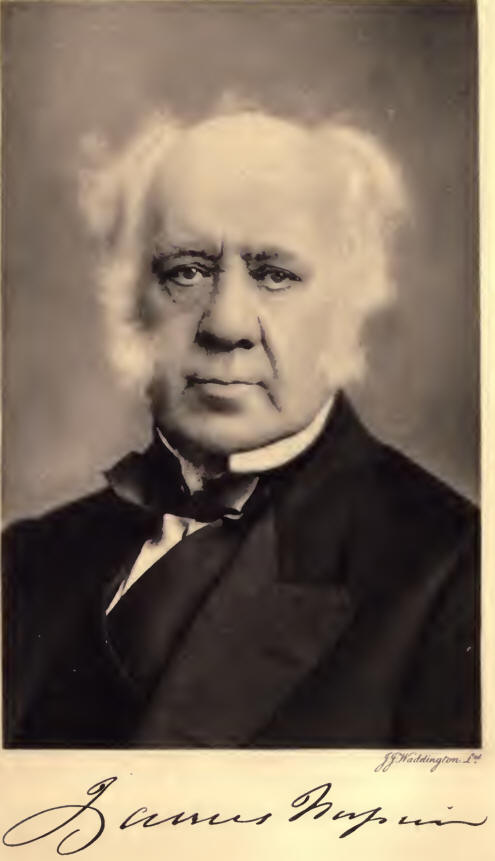

In this extremity he turned to his brother James, who

was then in partnership with his cousin William, under the style

of “ James & William Napier.” This firm owned the Swallow Foundry in

Washington Street, and had a good reputation as engineers and boiler

makers. James Napier was the inventor of the tubular boiler, for

which he took out a patent in 1830, and in the same year introduced

it successfully into steam vessels. At first the introduction was

attended with no small difficulty, and, to use the inventor’s own

words, “his firm had to contend with ignorant and interested

prejudices, and to give guarantees of security, and submit to

penalties and responsibilities in their contracts for these boilers

which no other engineer in the regular course of his business would

ever submit to.” He was a great authority on boilers, and his report

submitted to the Admiralty has already been referred to.

A patent for a steam-carriage was taken out by him in

conjunction with his Inveraray cousin, Mr David Napier of London,

grandfather of the present well known maker of motor-cars. At that

time, however, the difficulty of constructing a light and

satisfactory boiler was insurmountable, and the carriage was not a

success.

It may also be mentioned that James and William

Napier were among the first to build steamers of iron, a material

then only beginning to be used for shipbuilding.

No great inducement was offered to James to give up

his own business, where he had overcome the initial difficulties,

and in which he had good prospect of success; but being very loyal

to his eldest brother, who had a personal ascendancy over all the

members of his family, he was persuaded to dissolve partnership with

his cousin and come to Vulcan Foundry to take charge of Robert's

commercial affairs. The oversight of financial concerns was hardly

his role, as his bent was mechanical; and though overshadowed by his

brother, he was perhaps the more able engineer of the two.

While he endeavoured to confine himself to general

business, his engineering instincts occasionally asserted

themselves. Thus at the time when the side-levers in some of the

Cunard vessels cracked, and Elder, the manager, attributed the cause

to defective iron, suggesting as the only remedy that these

ponderous pieces should be made entirely of brass, thereby making

the cost of this type of engine prohibitive, James Kapier pointed

out that the fault lay in bad design, due allowance not having been

made for expansion. He predicted further failures, which actually

took place, and in the end his suggestions for remedying the defects

were adopted.

At a later date, when in London, viewing the Great

Eastern while she was on the stocks, he gave an opinion that the

launch would not be successful, as he personally had experienced

trouble with launching vessels broadside. The secretary of the

company, who did not happen to know him, derided his remarks as the

views of an ignorant man, and he was somewhat surprised at Mr

Napier’s acquaintance with Mr Scott Russell when the latter

cordially welcomed him. As is well known the launch was

unsuccessful, trouble arising exactly in the way Napier had

anticipated. While regretting the accident, he could not forget the

secretary’s incivility, and the paragraph announcing it was promptly

cut out of the newspaper and sent him, with the grim remark, “From

Mr James Napier, the result of his experience.”

James Napier's connection with his brother's business

lasted from 1841 till a short time before his death, which took

place in 1873. During this period he kept a sharp control over the

financial arrangements, and there is no doubt that his brother was

much indebted to him for the supervision of his commercial affairs,

which were left entirely in his hands. He was a fearless man, of

sterling upright character, a great favourite with all, and

familiarly known by the workmen and others as “Uncle James."

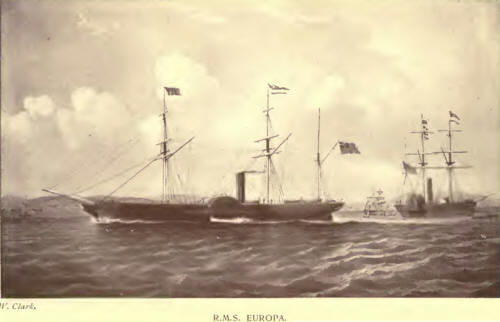

Outside of his immediate establishment the person

with whom Mr Napier came into closest business connection was his

much esteemed friend Mr Wood, who built the hulls of most of the

wooden steamers which he engined. John Wood was born in 1788, and

learnt the elements of his profession from his father, who was a

shipbuilder in Port-Glasgow. With a view to acquiring the best

knowledge of his trade he went to Lancaster, then a shipbuilding

centre, and served under a Mr Brocklebank for two years. There was

an interesting parallel between his early days and those of David

Napier, as, owing to his father’s death in 1811, he had to undertake

the task of constructing the Comet, which his father had contracted

to build. He subsequently built a great number of river-steamers

engined by David Napier, and afterwards steamers for deep-sea

navigation engined by Robert Napier, the largest of these being the

Cunard steamer Europa.

Mr Wood, while possessing the most eminent

attainments, was of a very modest and retiring disposition. He was

the most celebrated builder of wooden ships of his time, his vessels

being specially strong,and having a reputation for beauty and

symmetry of form. Mr Napier was so satisfied with his work that he

wished him to construct all the first steamers Mr Cunard ordered ;

but he would only undertake one, the Acadia. Writing to Mr Wood in

1841, he says : “I have uniformly in England and Scotland held you

and your work up as a pattern of all that was excellent, and I have

never yet had it proved to me that I was mistaken."

Mr Napier’s only sister was married to Mr Archibald

Reid, and on his death in 1837 his business was taken up by Mr Wood,

Mr Napier, Mr M'Intyre, and Mr John Reid, who carried it on under

the style of Messrs John Reid & Co.

With the advent of iron shipbuilding Mr Wood’s trade

was gone, and he practically retired, his business being merged in

Messrs Reid’s firm. In his latter years he resided at Port -

Glasgow, where he died in 1860 in the seventy-third year of his age.

One of the few enterprises outside his own business

with which Eobert Napier was connected was the Muirkirk Iron

Company, which he joined in 1834, Mr Ewing of Strathleven being then

the chief proprietor of the works.

Lord George Bentinck was manorial lord of the

Muirkirk estate, and being on intimate terms with Mr Assheton Smith,

he took a special interest in his friend’s acquisition of shares in

the Company, and wrote him several letters on the subject. His views

on the purchase were expressed in the following letter :—

Harcourt House, March 5, 1834.

Sir,—I have to apologise to you for not having sooner

acknowledged the honour of your last letter. The fact is I have been

so much engaged with the business of Parliament and of my

constituents that I really have had no time to attend to my own.

Since I received your letter I have spoken with Mr

Ewing, who agrees to postpone all further discussion of the subject

till we can all meet in town at the end of April or beginning of

May.

I hear from Kilmarnock that you and Mr Hamilton have

met, and that you have absolutely purchased Mr Yuill’s share for a

price equivalent to £11,500 for the whole. I sincerely trust you may

not find that you have paid too dearly. My valuer estimated the

materials of the work at £6812, 18s. 2d., and the Company’s estimate

did not exceed £7089, 16s. 2d. The stone, mortar, brick, and

wood-work of course are worth nothing to sell, whatever they may

have cost in the original erection. Of course, therefore, had the

works been abandoned, £7089, 16s. 2d. would have been the outside

price that the Company could have obtained for the works; and it is

therefore all that you should have paid for them. It is true that

when I stated this to Mr Ewing that gentleman threw out a hint that

he would batter down the walls with a park of artillery rather than

sell them standing for the breaking-up price ; but I need not say

that he must have been in joke and could not have been in earnest,

for considering the fatal effects of such a course of conduct upon

the existence of his old servants the Company’s workmen, he must

have been worse than an African savage or a Muscovite barbarian, —in

fact, he must have been a devil incarnate to have entertained

seriously for one moment so monstrous a thought. But Mr Ewing is

proverbially a warm-hearted man, with a polished mind, and of

course, therefore, as I said before, he was merely in joke.

Now in reference to my mention to you in a former

letter that Mr Ewing had represented the profits of the Muirkirk

Iron Works to have been in two separate years once £17,000 and the

other time £30,000, you will recollect that I did not guarantee the

fact, I only guaranteed the statement by Mr Ewing of such being the

fact. With respect to the fact itself, of course, as I was not at

that time manorial lord of those works, I could of my own knowledge

know nothing. And it is fair to say that I am inclined to be of

opinion that Mr Ewing is apt to think his geese swans, and

especially on that particular occasion when, in trying to persuade

me to give £20,000 for the works to the real intrinsic and bona

fide value of which I have above referred, I really do believe he

talked and wrote not me but himself into believing that the whole

concern had been much more profitable, and was altogether a much

finer thing than the reality could warrant.

I have troubled you at too great length, and in

having done so I beg to apologise, whilst I have the honour to

remain, Sir, your obedt. humble servant, Gr Bentinck.

To R Napier, Esq.

Napier’s connection with Muirkirk extended over a

period of ten years, during which time he acted as the Company’s

engineer. He gave great attention to the business, and made frequent

journeys to the works, which were managed by his friend Mr Carswell,

through whom he had been induced to join the enterprise.

Lord George Bentinck was a shrewd man, and his views

regarding Muirkirk were in the main correct. The business was far

from lucrative, and on the expiry of the contract of copartnery

Napier was glad to terminate his connection with it. |