|

By the year 1830 Robert Napier was the most prominent

marine engineer in Glasgow, and in order to meet the constant

demands made on him for new steamers, he equipped the Vulcan Works

with heavy tools suitable for making large engines.

In this matter he was ably advised by Mr Elder, who

was far-seeing, and kept well in advance of the times. Almost no

steam-boat line was now started without

consulting Napier, and he took an active part in forming new

companies for running steamers. Among many such undertakings special

mention may be made of the early steamers on the Belfast Trade, the

Londonderry Company, which still exists (dating from 1816, and

claiming to be the oldest Steam-ship Company in the world), and the

City of Glasgow Steam-Packet Company, in which lay the kernel of the

future Cunard Line.

We noticed in a former chapter that the first engine

Napier made at Camlachie Foundry was for Mr Boyack of Dundee, and

that it had given satisfaction.

In the summer of 1832 the Dundee, Perth, and London

Shipping Company, with which Mr Boyack was connected, resolved to

adopt steam vessels. Mr George Duncan, M.P., who took a prominent

part in the affairs of the Company, consulted Napier on the project,

and he gave him a favourable opinion of its chances of success,

basing his estimate on the results of the Liverpool boats with which

he was connected. Plans and offers were asked from prominent

engineers in London, Glasgow, Leith, Aberdeen, and Dundee. A

committee was appointed to consider the tenders, and they

unanimously came to the opinion that “the offer by Mr Robert Napier,

engineer in Glasgow, to furnish two vessels of 604 tons burden and

about 260 horse-power each, combined the greatest advantage to the

Company, and that it would be decidedly for their interest to accept

of it in preference to any of the other offers. They accordingly

contracted with him to build and engine two vessels for the sum of

£36,000 sterling. The Company required security for the implementing

of the contract, and one of the cautioners was Mr David Maclver of

Liverpool, who, hearing of the business, in a very handsome manner

voluntarily offered to become security for his friend. Napier, in a

letter written in 1835, mentions that he lost more money by this

contract than by all the work he had done since he commenced

business. Yet he spared neither trouble nor expense to make these

boats the fastest and most splendid mercantile steamers afloat,

implementing not merely the specification, but giving much more than

the contract stipulated for. They were called the Dundee and Perth,

and were considered very large steamers, their dimensions being 175

feet long and 28 feet beam. The hulls were built by Mr John "Wood of

Port Glasgow, who was then reckoned the best builder on the Clyde.

During their construction they came under the notice of the French

Government, who thought of acquiring them for their Toulon and

Algiers service. The Dundee Company expressed its willingness to

part with them in consideration of a profit of £10,000; but in the

end the negotiations fell through. When the steamers were completed

they gave unqualified satisfaction, and the following is an excerpt

from the minute of the meeting of the Directors of the Company held

on 12th May 1834 :—

The meeting (now that the steam-ship Perth, the last

of the two steam-ships contracted for with the Company by Mr Robert

Napier of Glasgow, has been taken off his hands and arrived safe in

the Tay) unanimously agreed that the Manager shall be instructed to

convey to Mr Napier the expression of their entire satisfaction with

respect to the honourable manner in which he has discharged his

obligations to the Company for building, furnishing, and fitting-out

these vessels, and of their opinion that in so far as they can judge

with reference to the mould and strength of the hull, the power and

finishing of the engines, and the comfort and the elegance of the

cabins, he has in every respect equalled, and in many respects

exceeded, the terms of the contract.

The success of the Dundee boats contributed to the

establishment of Napier’s general reputation more than any work he

ever did. Plying to the Port of London, they came in for a severe

ordeal of criticism, out of which they emerged triumphant and

universally admired. Large numbers of people flocked to see them on

account of the reported sumptuousness and finish of their cabins,

and they became one of the sights of London. The cabins, indeed,

were most luxurious, the panels in the saloons, which were painted

by a rising artist, who afterwards became famous as Sir Horatio

M'Culloch, being especially noteworthy.

The steamers ordered in 1832 were originally intended

to begin the service in 1833, but owing to difficulties with workmen

and other causes they were not ready in time for the summer season,

and the Dundee did not make her maiden voyage till April 1834. Mr

Duncan, the Chairman of the Company, wrote to Mr Napier, who was

also a shareholder, giving him the following particulars :—

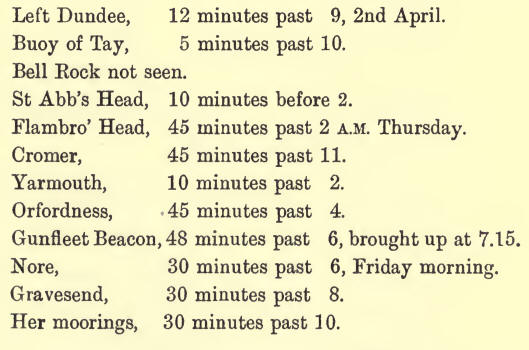

Dundee, Monday, 11th April 1834.

My dear Sir,—I have only time to quote to you part of

our agent’s letter received this morning :—

“I have great pleasure in saying the Dundee steamer

is safely up this morning, Captain Wishart highly pleased with her

operations. I give you copy from his log-book for your information,

that you may judge of her speed.

“There was a head-wind all the way to Cromer. We

consider she has made her voyage, fair steaming, in thirty-eight

hours. The ‘Pool’ was full, but she came through without touching so

much as a barge. I had an opportunity of seeing the passengers as I

met her at Gravesend, and all seemed delighted with their voyage and

arrangements.”

I have no time to say a word myself, only believe me,

yours always, George Duncan.

The Company ordered a third steamer, called

the London, which was equally successful, and, as we shall see at a

later stage, she was specially mentioned by Mr Cunard “as the

description of vessel he required.” Napier took the Dundee contract

at a very low price, as it afforded him an opportunity of showing

what he could do in the case of vessels steaming continuously for

over twenty-four hours, and he took enormous trouble to ensure

success.

Although much burdened with business, which he had to

conduct single-handed, necessitating (among other labours) journeys

to London and elsewhere, which in those days were very tedious and

exhausting, he was now finding time for a little leisure. In the end

of 1833 he feued about eighteen acres of ground at Shandon, and here

he built a modest cottage, where he proposed spending the summer

months. It was only two or three hours’ journey from Glasgow by

river, and he was interested in the steam-boats which plied on the

Gareloch. It took him some time to get his house ready, and there is

a very interesting letter to Mr Duncan, with whom he had formed an

intimate friendship, from which we will make a few extracts. It is

dated White vale, Wednesday, 10 p.m., 15th May 1835 :—

“I should be very happy that your arrangements for

going to London were such that we could meet there, as I propose

going up to Liverpool with the new City of Glasgow, which starts

next week on her first passage; and from that I go to London to see

Mr Smith about a new steamer he wants me to make nearly as large as

the Dundee. I want also to see the India and Government people about

their steamers. I have had different letters from them, and sent

them three models. I learn £60,000 has been voted for two vessels,

and I have been advised by my friends in London to go up. I should

like to have a letter from you to Sir H. Parnell by way of

introduction, and probably you will take the trouble of writing him

before I go as to the object of my visiting London.

“My cottage at Shandon is getting nearly ready for

its inmates. The painter is papering and painting one or two of the

rooms, and the woodwork of one of them I am varnishing instead of

painting, the wood being so very clean that I thought it a pity to

conceal it. . . .

“My business, as you are aware, is mostly confined at

the Yulcan Foundry to the fitting up of engines and machinery for

steam-packet companies, who, I may say, are in almost every case as

good and secure as the Bank of England; and any other work I do in

general is for people who are as good as the generality of banks. I

am also connected with a coal-work, which till lately has certainly

been a sinking fund; but no other losses that I am aware of have

risen from it, but, on the contrary, within the last twelve months

it has begun to pay a little of the sunk funds. I hold one-fourth of

the Muirkirk Iron Works. This also has been a sinking fund but is

now beginning to do some good, and in less than two months I hope to

be able to inform you that it is not only doing some good, but much

good, as by that time I fully expect we will have another large

furnace in operation, and the rolling mill for bars and

boiler-plates also in play. I am interested in another work at Port

Glasgow, &c., &c. . . .

“I have four new steamers at the Broomielaw finishing

for public companies, and I have other two on the stocks, and the

whole of these vessels are from 15 to 20 per cent higher priced than

the Dundee and Perth.

“I certainly lost a good deal of money by your two

vessels, owing to the scandalous, I had almost said villainous,

conduct of the workmen, and the very low prices I had for your

vessels.

“I have indeed always had plenty of 'Sinking-Funds'

and the last two years has not decreased them—viz., the improvements

at Vulcan Foundry, in houses and machinery, and purchase of new

ground there; Muirkirk Iron Works, Barrowfield Coal Works, the

giving up of Camlachie Foundry to one of my brothers, purchase of

Shandon grounds, making do. and building cottages there, &c., but

notwithstanding all these—call them what you

please, goods or evils — I have hitherto (without entering any

further into particulars) always had 20s. in the pound for all

honest creditors, and a beefsteak and a bottle of wine over and

above for all friends such as you; and I trust the next time you

manage to come west that you will fulfil your promise of domiciling

with us at the coast eight days at least, and put us to the test. If

we cannot offer you wine, we may probably collect a little

mountain-dew for the benefit of your health; and if we cannot manage

that, there is some fine spring water not far off which may probably

do you as much good as any of the former. At all events you shall

have a share of whatever we can afford, and a hearty welcome, and I

know that is all you want. Mrs N. fully expects you, but not till

the good weather comes in. She probably may not go down till the

school vacation in June. I hope to have a short respite about that

time also, and should like above all things to spend a few days with

you among the Highland hills. . . .

“I hope you will be able to make some sense out of

this long letter, which has grown upon my hand. I have never said so

much to any person before about the different businesses I am

concerned with; but from the friendly interest you have taken in

writing me as you have done, I think it due to you to detail a

little.—Yours most sincerely,

“R. Napier.

“P.S.—Do not forget Sir H. Parnell’s letter of

introduction to me.”

This postscript was a most important injunction, and

a few months later he writes Mr Duncan informing him that he has got

the yacht from Mr Smith, and also that he has succeeded in obtaining

the contract for one of the two steamers the East India Company

ordered. He adds: “What is more, they have given me my own way with

the vessel, trusting to my honour in everything. The surveyor has

been thrown overboard along with his specification, so that if we do

not make a good vessel we will have ourselves to blame.”

The India Company’s vessel was called the Berenice, and

she was the first ocean steamer Napier engined. While costing nearly

£30,000, her dimensions were only slightly larger than those of

the Dundee, which she resembled in many respects, being a

paddle-boat with double side-lever engines, having three copper

boilers worked at low pressure. She was also fitted with expansion

valves, which gave very satisfactory results. In one of his letters

Napier says: “From the generous and kind manner in which Mr Peacock

acted towards me in giving me a carte blanche, as it were, about the

vessel, trusting to my honour to bear him out in the preference

bestowed on me by building and finishing the vessel in the best

style and with the best and most fitting material, so as to ensure

to the Company a first-rate seagoing steamer of a good model,

combining great strength and durability, for encountering and

standing the strong navigation of the Indian and Red seas, and of

carrying her cargo on a light draught of water and her guns on deck

without being crank, it has been my anxious study to make the vessel

in every respect such as would be creditable to Mr Peacock and

profitable to the Company.” The other vessel, called the Atalanta, was

built in London, and there was keen rivalry between the English and

Scottish constructors.

The Berenice left for India in the spring of 1837,

and Napier was much gratified at receiving the following letters

from her commander, Captain Grant.

Bombay, 24th June 1837.

My dear Napier,—This is a copy of my report to

Government of our arrival in Bombay. I have no time to write more. I

hope it will please you. Your noble ship has behaved well, and beat

the Atalanta by eighteen days.—Yours sincerely, G. Grant.

Captain Grant's Report.

Hear-Admiral Sir C. Malcolm, Bt.,

Superintendent Indian Navy.

Sir,—I have the honour to report the arrival of H.C.

steam-ship Berenice, under my command from England, having left

Falmouth on the 16th March at 11 p.m. and touched at Santa Cruz in

Teneriffe, Mayo, one of the Cape de Verd Islands, Fernando Po, Table

Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and Port Louis, Isle of France. At each of

these ports we took in coal, and were detained altogether twenty -

five days. We have been steaming sixty-three days, and run in that

time upwards of 12,000 miles, having averaged eight miles per hour

the whole voyage.

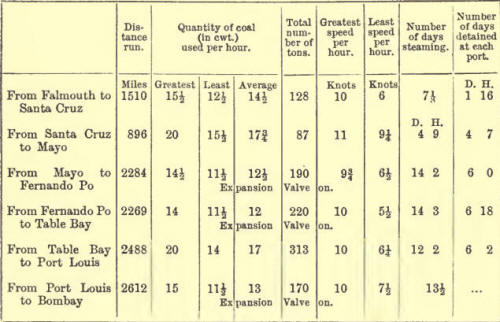

The following statement will show the distance run

betwixt each port we touched at, the quantity of coal consumed, our

greatest and least speed per hour, &c.The greatest and most

oppressive heat we felt during the voyage was soon after leaving

Fernando Po; the thermometer in the engine-room stood at 120

degrees, and in the coal-bunkers, where the men were working, it was

at 136. Our greatest run in twenty-four hours was 252 miles. I have

much pleasure in stating that the ship has performed her voyage in a

most satisfactory manner. She is an excellent sea-boat, and carries

her sail well in the worst of weather. We have not lost a spar with

the exception of a jibboom since we left England, and the masts,

yards, sails, and rigging are in good order. The engines and

boilers, with everything connected with them, are in the most

efficient state, and reflect great credit upon my chief engineer, Mr

David M‘Laren, who has proved himself to be a most excellent officer

and engineer,—his attention to his duty, and the good order he has

kept his men in, merits my warmest praise. The ship I consider to be

at this moment in almost as efficient a state as when we left

Falmouth, and perfectly capable of undertaking as long a voyage as

that she has just now so satisfactorily finished.

The ship’s log-book, with a copy of the steam-log,

shall be sent to you as soon as they are completed. The latter has

been kept by the purser and chief engineer, and the original was

sent regularly to the Hon. the Court of Directors by their orders

from each port we touched at. Mr Spear, the purser, was originally

engaged as 2nd officer of this ship, being well acquainted with

steam; but in consequence of a defect of vision I was under the

necessity of relieving him from that duty and appointing him purser,

and to appoint Mr Bennett, the then purser, to be 2nd officer. Mr

Spear has ably assisted at keeping the steam-log, and in all other

respects performed his duty to my satisfaction. The ship expenses

for fresh provisions, water, port charges, &c., amount to £217, 10s.

8d. since we left Falmouth.

Before concluding the report, I must beg leave to

bring to your notice the very meritorious conduct of my surgeon, Mr

Morrison, for his humane and kind attention to the sick, and having

voluntarily given up his own cabin for their accommodation for

nearly the whole voyage when I had no place fit for them.

Five boxes of the Hon. Company’s despatches accompany

this letter. They are directed to the Right Hon. the Governor in

Council of Bombay. I beg to enclose a copy of our muster-roll, and

have the honour to be, Sir, your most obedient humble servant,

G. Grant, Captain R.N.,

Commanding the Berenice.

Steam-ship Berenice,

Bombay Harbour, 13fA June 1837.

The success of the Berenice was one of Napier’s first

triumphs over his English rivals. It helped to dissipate the

prejudice against Scottish engineers, and establish the reputation

of the Clyde as an engineering centre. In proof of this it may be

said that the connection then made with the East India Company and

their successors lasted uninterruptedly till Mr Napier’s death.

As a result of the satisfactory execution of this

contract a most intimate friendship was established with the

secretary, Mr James C. Melvill, who had unbounded influence in the

direction of the Company’s affairs, and, as we shall see, it was

through his direct agency that Mr Cunard sought out Napier a few

years later. |