|

In 1821 Robert Napier entered into a lease of his

cousin’s premises at Camlachie, and removed his dwelling-place to

White-vale. The rent of the foundry was £300 a-year, including the

use of tools; but as this sum was more than ten times what he had

been paying for his old shop, and as there was considerable risk in

the venture, he had the option of giving up the lease at the end of

the first year. Though a great advance on what he had hitherto been

working with, the plant at Camlachie was of the most modest

description. There were a few 10-inch and 12-inch lathes, a rude

horizontal boring-mill, a vertical machine, and the necessary

appliances for making castings; but even with these tools he

succeeded in turning out first-class work.

One of his first steps was to fix upon a good works

manager. In making this selection, he was most fortunate in securing

the services of Mr David Elder, who continued with him for forty

years. Mr Elder came from the east country, and was a very sterling

upright man. He was a millwright to trade, and would turn out

nothing but the most solid work, on which he put the most accurate

finish. He was nearing forty years of age when Mr Napier engaged

him, and a good deal of millwright work had previously passed

through his hands.

Established in his new premises, Napier undertook a

contract for large water-pipes for the City of Glasgow, which he

executed satisfactorily. The first order for machinery came from Mr

Boyack, of Dundee. It was for an engine of 12 H.P., to be used in

driving a mill; and so well and substantially was this made that it

was running at the date of Mr Napier’s death, fully fifty years

afterwards. Orders of a similar nature followed, and he also made

numerous land engines. Robert Napier, however, perceiving that there

was a great future in steam navigation, desired more especially to

construct marine engines like those with which his cousin David had

been so successful.

Failures were then more frequent than successes, and

as he was an untried man as a marine engineer, he had great

difficulty in attaining his wishes.

Through his Dumbarton connection he was acquainted

with the Langs, and from them he ultimately, in 1823, succeeded in

getting an order for the engine of a luggage-boat they were about to

build.

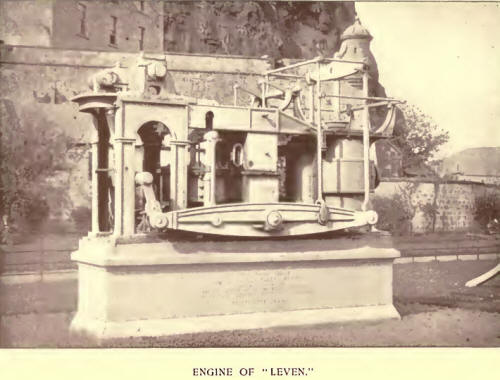

As so much hung on the satisfactory carrying out of

this contract, he bestowed on his first marine engine his best skill

and finish, introducing improvements on the condenser, air-pump,

slide-valves, &c., and taking special care to have the framework

strong and rigid. The Leven succeeded beyond his most sanguine

hopes, and her engine, after lasting out three hulls, finally found

a resting-place on a pedestal at Dumbarton Castle as a monument to

the constructor.

This order was speedily followed by others, and he

was now constantly employed as a marine engineer, constructing

machinery for river boats and larger vessels, such as the Belfast

steamers Aim-well and St Andrew, in the running of which he appears

to have been interested.

It may be noted that in the early days of steam

navigation the builder was frequently the owner of the vessel, and

it was generally owing to his initiation that new routes were

started. Thus in 1818 David Napier began the Belfast trade with his

steamer Rob Roy, and in 1826 Robert Napier made a further forward

stride in the same trade with the Eclipse, which he in great part

owned. At the time she was described as “the most complete vessel of

her size ever built on the Clyde; in point of sailing unequalled by

any vessel; built of the best British oak, copper-sheathed and

fastened, with double side-lever engines, having cylinders 35 inches

in diameter, warranted equal in construction and workmanship to the

best engines made.”

Being desirous of selling this vessel, and hearing

that some of the London companies wanted crack steamers, he went to

London in the spring of 1827, and stayed with his Inveraray cousin,

David Napier, who was then becoming known as a skilled mechanic,

especially in connection with the invention of the rotary

printing-presses, so much used in later years in the production of

the ‘ Illustrated London News’ and other papers.

Messrs Maudslay were then reckoned the most famous

engineers in London, and being desirous of seeing their works,

Napier approached them through his cousin, who had at one time been

in their employment. He received a most gratifying reply to his

request for permission to visit their premises :—

Mr Maudslay’s respectful compliments to Mr Napier,

and begs to say he always feels more gratification in meeting or

seeing any gentleman who has a knowledge of the business he is

engaged in than the thousands who go about taking up the time

without gaining any information. . . . Mr M. will therefore be glad

to see Mr N. either on the receipt of this or at 4 o’clock, or

to-morrow morning, Friday.

Lambeth, March 1, 1827.

This letter was specially complimentary, as the

London engineers did not then throw open their works readily for

inspection.

He was at this time living quietly at 31 White vale,

and there are few letters of general interest extant. There is,

however, one from his friend Dr Chalmers, who had just resigned the

charge of St John’s in Glasgow, on his appointment to the Chair of

Moral Philosophy in St Andrews University.

Kirkcaldy, November 13, 1823.

Dear Sir,—Having had no time in Glasgow, I wish to

thank you (now on my way to St Andrews) for the use that you so

kindly allowed us of a child’s coach, from which our little daughter

derived a great deal of enjoyment, and also of substantial benefit.

May I beg my most affectionate regards to Mrs Napier

and your brother.

I should have called along with Mr Sommerville upon

you for the purpose of introducing him to your acquaintance. This I

was not able to accomplish, but I hope that you will soon meet, and

that he will prove a blessing in the highest sense of the word to

your family.

It is my great wish that the chapel shall prove a

blessing to your immediate neighbourhood.

Give my compliments when you see him to your cousin,

David Napier, Esq.—I am, dear Sir, yours truly, Thomas Chalmers.

The brother Dr Chalmers referred to was the Rev.

Peter Napier, who was then assistant minister in the High Church, in

Glasgow, from which in the following year he was presented to the

church of St Georges-in-the-Fields, a charge then newly created. In

later years Dr Napier became minister of the Blackfriars, or what

was more commonly known as the College Church of Glasgow, a position

which he occupied till his death, which took place in 1865.

Robert Napier was now no longer an unknown engineer,

and his reputation as the best engineer on the Clyde was established

in 1827.

The Northern Yacht Club, at their regatta in August

of that year, offered a cup, valued at twenty guineas, for the

swiftest steam-boat. The course was from Rothesay Bay round boats

moored at the north end of the Great Cumbrae, and back to Rothesay.

Several steamers entered for the race. The contest was an exciting

one, occupying nearly three hours, but in the end victory lay with

Napier’s steamers, the Clarence winning the cup, and the Helensburgh coming

in a good second. This apparently trivial incident was one of the

most important events in his life, and had a material bearing on his

subsequent career.

Up to this point his life had been a laborious

struggle to obtain a subsistence, and his position little more than

that of an industrious master mechanic.

His success changed the situation. Orders, not only

from Glasgow but from other quarters, flowed in on him, and he began

to find himself in affluent circumstances.

He now entered into negotiations with his cousin for

the purchase of Camlachie Works which he had hitherto leased; and to

meet the growing requirements of his business he resolved to obtain

premises near the Clyde. A favourable opportunity presented itself

of acquiring the works at the foot of Washington Street, where Mr

M'Arthur had carried on business as a marine engineer, and he

availed himself of it. |