|

Agriculture is pursued in a

most enterprising and enlightened manner, and both in arable farming and in

the excellence of farm stock, the county takes a high position. Along the

coast the soil consists mostly of sand and loam, the latter by far the more

predominant, and these in several districts are blended with a proportion of

clay soil. The arable surface along the coast lies in general upon a free

open bottom, while that of the interior is mostly a light black soil on a

hard bottom, retentive of water, hence one of the causes of the lateness of

the crops in these districts.

Up to the middle of the

eighteenth century improvements in agriculture were few. The arable lands

were divided into outfield and infield. To the infield, which consisted of

the acreage nearest to the farm house, the whole manure was regularly

applied; the only crops cultivated on it were oats, bere and peas, and the

land was kept in tillage as long as it would produce two or three returns of

the seed sown. When the field became so reduced and so full of weeds as not

to yield this return, it was allowed to lie in natural pasture for a few

years, after which it was again brought under cultivation and treated in the

same manner. The outfield lands were wasted by a succession of oats after

oats so long as the crops would pay for seed and labour. They were then

allowed to remain in a state of absolute sterility, producing little else

than thistles and other weeds till, after having been rested for some years,

they were again brought under cultivation and a few scanty crops obtained.

There are authenticated cases of fields in Alvah and Boyndie which carried

respectively 12, 14, and rq crops of oats in succession. The system of

farming pursued was clearly described by Alexander Garden of Troup, writing

in 1686. The land as stated, was divided into "in-field" and "outfield." The

in-field was kept "constantly under corne and bear, the husbandman dunging

it every thrie year, and if he reap the fourth corne, he is satisfied." The

outfield was allowed to grow green with weeds and thistles, and after four

or five years of repose was twice ploughed and sown with corn. Three crops

were generally taken in succession and then, or as soon as the soil was too

exhausted to repay seed and labour, reverted to thistle and weeds. That this

system was regarded as completely satisfactory, is shown by the old proverb:

If the land be thrie year oot

and thrie year in,

'Twill keep in good heart till the Deil gaes blin.

If credit for the change is

to be given to one man more than another, it is due to James, sixth Earl of

Findlater and third Earl of Seafield (d. 1770). He was an enthusiastic

agriculturist, and practically transformed the face of his extensive

territories, a sober eulogist writing that to him appertained "the exclusive

merit of introducing into the North of Scotland those improvements in

agriculture and manufactures, and all kinds of useful industry, which in the

space of a few years raised his country from a state of semi-barbarism to a

degree of civilisation equal to that of the most improved districts of the

south." It was he who, about i 754, introduced in the north the system of

alternate husbandry. He took some of his farms into his own possession, set

about cultivating them in the most approved manner then known in England,

under the oversight of experienced men from the south, and in a few years

improved such farms as Craigherbs in the parish of Boyndie and Colleonard in

the parish of Banff as well as the fields about Cullen House in a manner

then unknown in these districts. He further granted to some of the most

intelligent and substantial tenants leases for two 19 years and a lifetime,

under which they became bound to enclose and subdivide a certain portion of

the farm with stone fences or ditch and hedge during the first 19 years, and

in the course of the second 19 years to enclose the remainder, while they

had to sow grass seeds on a certain number of acres within the first five

years of the lease. He was the first also to introduce turnip husbandry and

thus pave the way for the home-feeding of cattle during winter. Other landed

proprietors acted on a similarly enlightened policy. James, Earl of Fife,

granted leases to improving tenants of from 25 to 30 years, with an ample

allowance for building houses and dykes; and Alexander Garden of Troup

followed a similar practice.

By 1812, on the larger farms

where long leases had been granted, turnips were being laid down with

manure, and grass seeds were being sown with bere or oats. A further

improvement was effected when the broad-cast sowing of turnips gave place to

drill husbandry. In course of time the eight or ten owsen plough was

abandoned for an implement of greater tillage power hauled by horses, while

with the improvement of roads the double carts (carts, that is, with a shaft

and a trace horse to one cart) gave place to single-horse carts.

The system of holding land

under lease for a period of years still prevails. In the uplands the arable

area rises from the valley and ascends the hillside till it abuts on the

heather; and in these high-lying places account has to be taken of losses

through stress of weather and by game, so that in some seasons quantities of

reliable seed have to be imported from more favoured districts, all

circumstances that are, as a rule, reflected in the amount of the rental.

Wheat used to be grown to

some extent, but in this northern climate the quality was often indifferent

and the produce variable; and that, together with low prices and the poor

feeding qualities of the straw, has led to its practical disappearance. Oats

of the potato variety are chiefly grown; Sandwich oats, and more recently,

black oats, are also cultivated, while of late years the large American

varieties have been introduced. The standard weight is 42 lbs. per bushel. A

large part of the oat crop is manufactured locally into oat meal, but much

of it goes also to Newcastle and Leith, a considerable part for consumption

in the hunting districts. The barley grown in the county is not often of the

bright and attractive colour that is desired by brewers, but it finds a

large and remunerative market at local malt distilleries. The turnip crop is

vital to the industry of a county that is essentially a stock-rearing and

feeding area. During the long northern winter, cattle kept for breeding

purposes and young stock get little save turnips and oat straw, thriving

magnificently upon such a diet, while cattle that are in course of finishing

have supplies of feeding cake and second qualities of grain. Hay is for the

most part grown only for local needs. Flax, raised. in small quantities in

every quarter of the county a century ago, is now seldom seen.

There are in the county 3418

agricultural holdings of an average size of 46.8 acres. Of that number 2333,

or 68.26, have an area of from 1 to 50 acres; there are 1059 holdings of

between 5o and 300 acres, and 26 farms of over 300 acres.

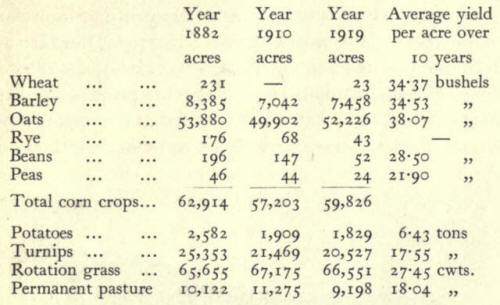

The area of the county,

excluding water, is 403,053 acres; and in the year 1919 there were under

corn crops and rotation grass 126,377 acres. The following figures show the

cultivation of crops at different periods, and the average yearly yield over

a period of ten years:

The county is very wealthy in

its pure-bred farm-stock. Of the native Aberdeen-Angus breed (indigenous to

the north of Scotland and now found, by its own great beefing merits, in

every agricultural country), Banffshire possesses the most famous collection

in the world—that of Sir George Macpherson Grant, Bart., of Ballindalloch,

one of the oldest herds of the variety and as famous on American ranches, on

the estancias of the Argentine, on the veldt of South Africa and in the New

Zealand bush, as it has for many years been in this country. All the world

over this great collection at the confluence of the Spey and the Aven is

regarded as the fountain-head of the breed. There are other Aberdeen-Angus

herds of great excellence in the county. The "great intruder," the

Shorthorn, has also found a favoured home. Eden and Rettie were among the

earliest seats of the breed in the north of Scotland, and in the case of

this as of the other great cattle breed, many of the local herds are well

known in national showyards and in the foreign trade. The commercial cross

cattle of the county are of a high standard, and in the most discriminating

meat market of the world, that of Smithfield, they are included in the

number of select cattle classed as "Prime Scots," and uniformly bring the

extreme price of the day. On several occasions cattle bred and fed in the

county have won the blue ribbon of the fat stock world—the championship of

the London Smithfield Show. At the Scottish Fat Stock Show and at the show

of the Smithfield Club in 1919, the champion and reserve champion of both

came from Banffshire herds on Speyside, a circumstance unexampled in the

agricultural annals of any county in the Kingdom.

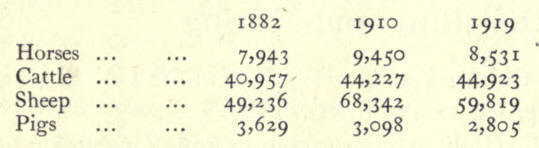

Of late years an increased

amount of attention has been devoted to Clydesdale breeding, and in the

production of strong active geldings for city use, the county enjoys a high

reputation. Sheep, too, are a valuable farming asset. There are some select

flocks of Leicesters and Cheviots, but there are larger numbers of

black-faced and cross-breds, which spend the summer months on the hills and

in the hard weather are wintered in the pastures and surplus turnips of the

low country. The possessions of the county in farm live-stock at different

periods have been:

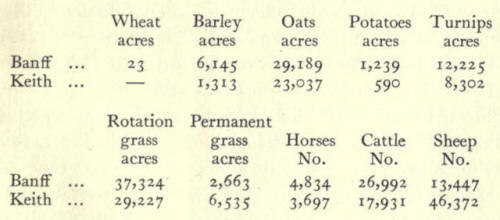

The difference in the

physical character of the two local government districts in the county is

well illustrated by figures of cultivation and live-stock. In the level and

fertile Banff district there are i 25,645 acres and in the more mountainous

Keith district there are 277,408 acres, while the principal figures of crops

and stock in 1919 were:

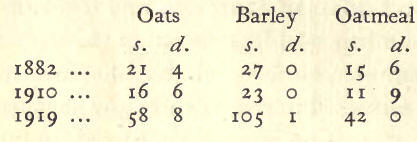

The value of the crops grown

in the county in the years mentioned is of interest. In the case of the

principal field produce the fiars prices struck were as follows, barley and

oats being both first quality and the price per imperial quarter, while the

oatmeal is per boll of 140lbs.:

|