|

Summary of Events from 1848 to 1871.—Building—Hydropathio

Establisbment.—New Cemetery.—Literature, Amusements, and Public Buildings.

—Climate.—Vital Statistics of the Parish—Tabular view of the same.-Sanitary

observances.—Moffat created a Burgh in 1864 under the General Police and

Improve mont Act.—Conclusion.

THE

change which has taken place in the external aspects of the town, even

within recent years, must be matter of no small surprise to those who, for

some years, have kept themselves aloof from the familiar scenes of their

childhood. The town, attractive as it is, has not retained much which

indicates the rudeness of mediaeval ages, though we fancy there are a few

things still existing which could claim their origin from that period, and

altogether it bears the plain architectural peculiarities of modern times.

The suburbs indicate, however, a more pretentious style, and the sometimes

extensive gardens, with their well-assorted plots of flowers which scent the

air with a kindly perfume, show plainly the care which is taken to render

the environments of the town an object of particular admiration. Free from

the restraints and conventionalities of city life, the inhabitants are ever

seen pursuing their daily avocations with earnestness and quietude—a state

of affairs which, harmonizing with the seclusiveness of the scene, stirs up

the suggestive lines of Coleridge—

"O! 'tis a quiet spirit-healing nook!

Which all,

methinks, would love, but chiefly he,

The humble man, who in his

youthful years

Knew just so much of folly as had made

His early

manhood more securely wise!"

It may appear necessary that a retrospective glance should be cast o'er the

path which, in this work, we have pursued. And while noticing its gradual

development, from the time when its church and church lands were part of the

private patrimony of Bruce, and by him subsequently annexed to the Bishopric

of Glasgow; from the time when its inhabitants were skilled in war, as the

turbulent state of the country necessitated, and when their industry and

perseverance were evinced in the manufacture of beverages to satiate their

appetites; or when the town was slightly exalted by its errection into a

Barony and Regality Burgh, and subsequently released from the partially

tyrannical control of a feudal Superior, we cannot but be satisfied with the

peaceful picture which it now presents. Former customs and institutions have

been rejected and abolished, former principles have by the inhabitants been

renounced, and in conformity with the times they zealously attend to their

domestic and agricultural duties. Under the paternal superintendence and

care of a prudent and far-seeing proprietor, the lands of Moffat, with many

in Annandale, have been efficiently taken care of and cultivated; and the

inhabitants of the surrounding district are to him much indebted for proper

systems upon which to work farms, with the same efficiency as formerly, and

with greater economical observance. The town, too, has not been neglected,

and here and there traces of his benevolence and interest in its prosperity

are visible, while the Moffatians readily acknowledge the benefits received

from his liberal hand.

Though

we are capable of enjoying the contemplation of Moffat in its ameliorated

state, we cannot be expected to derive full satisfaction from the prospect,

because we are practically unconscious of the change which has transpired in

its social, religious, and domestic aspects, in common with other towns of

small dimensions, struggling for existence at the same remote period, not

having in those primitive times gone abroad to enjoy the freshness of its

beauty, the sweetness of its solitude, or having conversed with the

associates of "Tam Hulliday of Corehead," the compatriots of William Wallace

in his fight for national independence, or the zealous adherents of the

Scottish Covenant, who dwelt within the precincts of the town, or in some

favoured spot of the surrounding country. To such, the change would by no

means appear an improvement. These octogenarians would doubtless account

with wondrous veracity the doings of their childhood, when the Bruce was a

more familiar sight than even some of our modem idols, who, from the purity

of their imaginings, the depths of their scientific discoveries, or the

number and variety of their philanthropic executions, are daily worshipped;

or the graver duties which in their declining years employed them, when the

caprices of youth had vanished, and when, desirous of keeping themselves

aloof from the wickedness which everywhere abounds, they repaired to

conventicles in secluded glens, where the serenity of the scene caused them

to raise their thoughts above Nature and her beauties, and concentrate them

upon Nature's God. What an ample illustration of these words-

"Oderunt peccare born virtutis amore."

How interesting it would be to hear them narrate in

thoir unostentatious manner their own daring deeds during the many quarrels

in which their country was implicated. To receive a vivid and glowing

description of the eventful battle of Dryfesands, with its attendant

fatalities—the temporary overturn of the ancient house of Nithsdale and the

ignominious death of its noble representative—would prove not the least

worthy of our attention. Or how they, flushed with enthusiasm, when they

beheld the saving and welcome rays which emanated from the fitful beacon

planted on the Gallowhill, which indicated the approach of the usurper, and

caused them to doff their daily habit for that which practically signified

their allegiance to their king and country. Or how, when the discovery of

Moffat Well was universally made known, they indirectly resented the daily

encroachments () made upon them by strangers attracted to the locality to

share its hidden health-restoring influences. Or how they were impressed

with the idea of their own importance when the town was elevated to the

position of a Burgh of Regality, partakers in the privileges of the same,

and under the direct control of the Baron and his bailies.4 To see it now

with its public buildings, its large churches, its baths, its commodious

hotels, its banking establishments, and educational institutions; its gas

and other conveniences peculiar to modem times, would be matter of surprise

and pain, not contented pleasure; and in the extremity of their grief they

would doubtless exclaim-.--

"Timeo

Danaos et dona ferentes."

The

improvements effected within recent years have been numerous, and may here

be briefly enumerated. For many years the impulse gained by the opening of

the Caledonian Railway in 1848 steadily increased, and the enthusiasm which

they manifested in their building projects has been productive of its own

good, as the unique and substantial appearance of the town is the object of

admiration of its numerous visitors, and the pride of its natives. Hartfell

Crescent has an airy and elevated situation facing the south, while its

architecture is tasteful and elegant, and the internal conveniences have by

the proprietor been particularly considered. A Company was recently formed

for the creation of a Hydropathic Establishment, which will add materially

to the attraction of a visit; and several acres of ground have been

purchased at a heavy sum for the erection of a suitable Institution, and

schemes organised for the practical development of the plan. It may also be

observed that the Parochial Board, with the Rev. Dr. M'Vicarat its head as

Chairman, has secured in perpetual fen, from Mr. Hope Johnstone, a lovely

and sequestered spot on the banks of the Aman, for the purpose of forming a

Cemetery, its chief attraction being its remoteness from the town. This will

be a great boon to the inhabitants, as the present burying-ground is already

inconveniently filled "with moes.green'd pediments and tombstones gray." And

although they must henceforth bury their dead in a more remote but still

more lovely spot, they can ever with a saddened pleasure point to the

southern extremity of the town, and in the pathetic words of Gray exclaim:-

"Beneath those rugged elms, the yew-trees' shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell

for ever laid,

The rude

forefathers of the hamlet sleep."

Moffat also possesses a Horticultural Society, whose

indefatigable exertions to have an annual exhibition are signally rewarded,

and the elite of the town during the visiting season favour them with their

presence. But this is but one of the many treats which the Moffatians hold

out to strangers as an inducement to sojourn for a time in the locality.

Concerts are held at stated intervals within the commodious hail in the Bath

buildings, which are well patronised and meet with the universal approbation

of the visitors, and the committee of management merit praise for the

efforts which they make to secure the services of talented arti3tes during

the season. Assemblies, lectures, and evening meetings of various types have

been instituted, all of which are calculated to while the time pleasantly

away, as they offer the privileges of new associations, drawing the visitors

closer to each other, and makes the less homely tendency of our Scottish

watering places much reduced. And, while endeavouring to originate schemes

for the amusement of all, the inhabitants have not forgotten the moral and

intellectual power which, in common with all great or small communities,

they possess. Since 1622, when the first known English newspaper was

published in the form of News of the Present Week, the cry for serial

literature has increased to such an extent that no small provincial town is

now destitute of its "Weekly," with its "Public Voice," through the medium

of which existing evils are assailed, and its leading articles, pregnant

with unvarnished sarcasms, by which parliamentary enactments and public

measures may receive the approval or disapprobation of the editor and his

coadjutors, all of which have a decided tendency to impress their local

readers with the idea of the immensity of their achievements and give an air

of importance even to the most humble. Moffat has long since experienced the

benefits arising from local newspapers, and various series of the Ho/at

Times have been called into existence and suppressed. The present issue,

which may be said to be a better speculation than any of its predecessors,

was originated in May, 1861, and is conducted under the superintendence of

its proprietor, Mr. Muir. Ample means for the amusement and instruction of

the inhabitants is provided in the Public Library, consisting of upwards of

4000 volumes, chiefly the benefactions of eminent natives, and also under

his care and management.

We

deem it necessary to consider the suitability of the climate for invalids.

It has all along been objected that Moffat is anything but desirable winter

quarters, an impression which, though erroneous, has gained ground, and

hence the comparative brevity of the visiting season. Its mountainous

surroundings and elevated situation are apt to impress strangers with the

idea of the severity of its winters, but from personal experience we can

testify to the contrary; and recommend it for the winter residence of all

who are desirous of escaping biting east winds or fogs, for which cities are

famous, as the prevailing winds of Moffat are southerly and westerly, and it

is almost free from the annoyance of fogs. Another advantage is the peculiar

construction of the streets, or the material with which they are formed.

After a heavy shower of rain, the streets are in such a state as to admit of

the most scrupulous invalid taking a walk without deriving the slightest

harm. Though we claim for Moffat during the winter months the title "mild,"

we must confess to a few exceptional cases illustrative of unusual cold. On

Tuesday evening, 30th September, 1817, the thermometer at Moffat was as low

as 27°, and on the following morning at 23°, exactly nine degrees below

freezing point. But there are exceptions to all rules, and this is one. Dr.

M'Vicar, speaking of the temperature, says, "The niininum of this winter

[1870-71], indicated by a trustworthy, self-registering thermometer hung on

the wall of this house [the Manse], at the height of the eye, protected from

the sky and passing influences, by being among the loaves of a cotoncaster

nailed to the wall, is nothing lower than 17° Fahr."

There have been many instances of

longevity in the town and parish, which can be accounted for by the

healthful recreations and pursuits of the inhabitants, and the efforts which

have been made for sanitary reform. The populations have, in a former part

of this work, been noticed—that of the parish 2232, of which number 1600

inhabit the town—and the following statistics are given with the view of

illustrating the remarkable vitality in Moffat and upper Annandale. In 1870,

the deaths of parishioners out of that population were 34, eight being

upwards of seventy years of ago, which is much less than the mortality in

even lees populated towns or rural districts in Scotland, as it is only 152

per 1000; while in 1869, the general mortality rate of small towns was 222

per 1000. And what proves beyond dispute the benefits accruing from the

drinking of the mineral waters, and the invigorating air for which Moffat is

famous; is, that out of 5000 strangers who resided in the town during the

visiting season, as estimated, four deaths only occurred. And this is

particularly striking when we consider that many who constituted the 5000

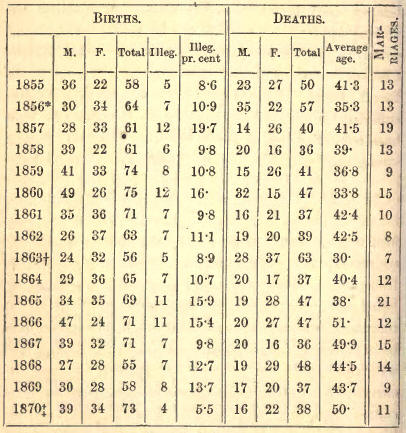

were afflicted with some direful malady. The following tabular view of the

vital statistics of the parish, prepared by Mr. Gibson, M.C., Edinburgh

University, the Local Registrar, and procured through the kindness of Dr.

M'Vicar, may more fully illustrate the preceding remarks:-

The reader, by perusal of the foregoing statistics,

will readily perceive that Moffat has an exceedingly insignificant mortality

rate, and with a continuance of the care which is taken to free the town

from bad or imperfect sewerage ;* and other sanitary observances, it may in

time coming merit the appellation which it has in time past received. There

is no known local distemper, and it has even providentially escaped the

violent epidemics which have frequently ravaged the country. In the

memorable year 1832, when Asiatic Cholera visited it; and when the

inhabitants of the Royal Burgh of Dumfries (21 miles distant) were suffering

from the Pestilence which ruthlessly slew hundreds of them, so much so that

the words of Armstrong can best illustrate the direfulness of the malady,

In heaps they left, and oft one bed, they say, The

sickening, dying, and the dead contained,"

Moffat was spared. And the wonder is increased when we

consider that daily communication was made to and from the "town of the

plague," in the form of parties being conveyed to a purer atmosphere, and

yet Moffat remained uncontaminated. Although this may justly be attributed

to a special provision of Providence, still we cannot shut our eyes to the

palpable fact that the cleanliness of the people, and the care taken by

their rulers, rendered the possibility of a similar attack less likely. The

cleanliness of the town and inhabitants of Moffat is nowhere surpassed. But

Dumfries was, at the time of which we speak, unfortunately differently

situated. The condition of the lower classes had long been sadly deplored,

and called for immediate action; the state of their homes was of such a

filthy character that a like visitation had been sincerely dreaded; sanitary

reform amidst much disease had been Unheeded till the reaper Death, with his

"sickle keen," had in towns not far distant been vigorously plying his

vocation. Then, and not till then, schemes were organised for the practical

development of sanitary plans, which had hitherto remained unheeded, and so

when the plague entered the town their feeble efforts could not allay the

virulence of the disease. Moffat, however, had long recognised the strict

necessity for instant and constant action for the relief of the destitute,

and the systematic cleansing of the town. A sufficient supply of pure water

was always possessed, and the houses were in such a state as would in all

probability ward off the attacks of such an unmerciful foe.

The most fortunate move Moffat ever made was the

adoption of the General Police and Improvement Act, which formerly the

inhabitants had made strenuous efforts to acquire, as this may be regarded

the parent of all subsequent improvements and the cause of the numerous

changes made in the external arrangements of the town, for when efforts were

made to obtain a new Cemetery, somewhere about 1856, the Burgh's boundaries

had first to be specified, and power procured ere they could more at all.

And after the lapse of eight years their darling object was realized, for in

1864 the town was created a Burgh under this Act, making all the

improvements since effected a matter of comparative ease, seeing the power

of acting freely had been acquired.

It is with considerable reluctance we tear ourselves

from the self-imposed task which has for the past two years employed us.

Conscious, however, of the size which it at present assumes, we cannot

confidently enter into a more detailed account of the present position and

growing importance of the town. Though self-imposed, the task latterly

became burdensome when the time was limited for its completion, and this in

some measure accounts for the abrupt conclusion which we are bound to make

of a somewhat lengthy story. Strangers necessarily ignorant of Moffat's

beauty may consider the statements herein made exaggerated, and attribute

them to the over-heated imagination of the writer, but to them we

Particularly recommend a visit, so that experience may prove the falsity of

such a supposition. The number of visitors is yearly increasing, and well

may we say with Cowper, in support of our former assertion

"Scenes must be beautiful which daily viewed

Please daily; and whose novelties survive

Long knowledge and the

scrutiny of years

Praise justly due to such as I describe."

We affectionately bid our readers farewell, wishing

fir Moffat a continuance of that prosperity and public favour which hitherto

it has received: trusting, too, that the object of the author's heart has

been realised —to bring it prominently before the public, and in every

respect make his results worthy of the subject handled.

|