|

Picture of Moffat in 1704-Its

Gradual Development, as shown in 1746—Visitors—Discovery in 1748 of Bartfell

Spa—Notice of the discoverer, John Williamson—Various analyses of the Water,

with remarks thereon—Houses in the Town owned by the Marquis of

Annandale—Building of Moffat House—Picture of Moffat In 1770.—State of the

town in 1791, with reference to the Poor.—Moffat as a Market Town—Increase

of the Revenue of the Burgh by the Markets—Its Trade—Changes effected by it.

FROM external signs we are apt to suppose that the

prosperity of Moffat has ever been fluctuating. At the particular time of

which we speak, one year it stands smiling in its peaceful beauty,—every

external image indicating its completeness and lack of nothing; while in

another, the aeronaut traversing its perfect streets and sunny by-paths may

detect the want of that hopeful smile of future glory formerly depicted on

its exterior, and in its place behold something which has a decided tendency

to impress us with the idea of doubt as to its future power and fame. This

is not owing to a diminution of visitors, "invalids with lameness broke," as

far as can be seen. In fact, no reason can be assigned for this combination

of seeming poverty and prosperity, save that the gossipping chroniclers to

whom we depend for information regarding the aspect of Moffat at such dates,

being of supposed English extraction, had their ..eyes jaundiced with

prejudice to the self-evident beauties of a Scottish town. Judging from a

sketch of Moffat in 1704, now before us, as represented by one of those

in-embryo historians, we fancy the reader will detect the want of sincerity

and truth in the statements of a writer talking of Moffat in 1679,

previously quoted, if we are to give credence to the following:—"On the 17th

of April, 1704, I got to Moffat. This is a small straggling town among high

hills, and is the town of their wells. In sumer time people comme here to

drink waters, but what sort of people they are, or where they get lodgings,

I can't tell, for I did not like their lodgings well enough to go to bed,

but got such as I could to refresh me, and so came away." The Reverend Dr.

Alex. Carlyle gives us something illustrative of the gradual development of

the town. Writing in 1745, and while speaking of dno Dr. Sinclair, he

says—"He (Sinclair) and Dr. John Clerk, the great practising physician, had

found Moffat waters agree with themselves, and frequented it every season in

their turns for a month or six weeks, and by that means drew many of their

patients there, which made it be more frequented than it has been of late

years, when there is much better accommodation." Within the period of

forty-one years Moffat's comforts had been considerably augmented, and its

popularity and prosperity had increased. We have already alluded to the

improbability of its having been in early times a place of fashionable

retreat, and we fancy the preceding remarks of Dr. Carlyle fully exemplify

this. It is absolutely impossible for Moffat to have been resorted to in

1679 by fashionable circles unless desirous of obtaining health and lost

vigour through the medium of the mineral wells. In fact, as far as public

patronage went at this date, it might almost be spoken of as a terra

incognita. Even at the more modern period (1745) we find the well the cause

in chief, the principal attraction, the "mere matter of health" (as a writer

to whom we have casually referred in a former part of this work has been

pleased to denominate it), and faith in the curative power of the water

drawing people to its friendly shelters, who had felt the evils arising from

being "long in populous city pent," or who from other causes needed the

combined beneficial influences of the mineral water and the invigorating air

to render their state more agreeable.

In 1748 the prosperity of Moffat was somewhat

augmented by the discovery of another mineral spring —Hartfell Spa. Its

discoverer, John Williamson, was apparently one of the "worthies" of the

place. Members of this sect, humorously denominated "worthies," are seen

everywhere, and nowhere so abundantly as in provincial towns, and Moffat to

all appearance has been inundated by those whose education in deportment and

polite manners has not altogether been neglected, and who scorn at

manifesting frankness and candour by openly soliciting alms, but who, from

their civilities, eccentricities, and little kindnesses done by them, merit

the enviable appellation of "harmless creatures," and assuming the position

of pensioners, become the objects of the visitors' charity. The successors

of John are, however, not of the same species. They are of a less worthy

type. His peculiarities lay in an entirely different direction. At one time

his principal amusement consisted in scouring his native hills in pursuit of

game, but his feelings were evidently of an exceedingly sensitive cast, and

consequently he abandoned the sport for a trick of a more sombre aspect—he

determined to encourage no longer the sale of flesh meat by personal

consumption, and to make his con-elusion worthy of his former and almost

unprecedented conduct, he ultimately gave himself up to the absurd belief in

the transmigration of souls. John (lid not long survive the declaration of

his discovery, but his name has been perpetuated in a monument erected over

his grave in Moffat Churchyard by Sir George Maxwell, the inscription

thereon fully explaining his accomplishments—

"In Memory of Jno. Williamson, who died 1769.

Protector of the Animal Creation,

The Discoverer of Hartfell Spa, 1748:

His life was spent in relieving the distressed.

Erected by his friends,

1775."

This is certainly a

good character, but we scarcely fancy the discovery of the Hartfell Mineral

Spring, if properly viewed, will add much importance to his name. Altogether

it may be said that the respect given him after death exceeded the value of

the discovery he made. And this becomes more decidedly apparent when we

consider that Miss Whitefurde, to whom the prosperity of Moffat is much

owing, has been absolutely neglected. In every respect the value of the

mineral water which proceeds from the Hartfell spring is over-estimated, but

by parties alone who know nothing concerning it, either with regard to its

medicinal properties or the particular cases in which it should be applied.

Some have had the arrogance, in the face of medical reports, to state, that

this water is better than the other, inasmuch as it preserves its medicinal

virtues for a great period. And what makes things still worse is the fact

that, analysts of former times, such as Garnett, have failed in reality to

understand the nature of the waters, for they, too, in a slightly modified

manner, corroborated this statement, shown in 1854 by Dr. Macadam to be

absurd. Garnett says, "The water of this spring may be kept long without

injury to its medicinal powers." This idea having been promulgated by Dr.

Garnett, people were struck by it, and accordingly sent it as far as the

West Indies, in the vain hope that it would retain its curative powers. Dr.

Macadam has, as will presently be shown, proven this statement to be

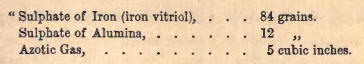

unfounded. The following is Garnott's analysis:-

"The water of this spring may be kept long without

injury to its medicinal powers. It is a powerful tonic of proved utility in

obstinate coughs, stomach complaints affecting the head, gouty ones

disordering the internal system, disorders to which the fair sex are liable,

internal ulcers, &c" It has been hinted that Dr. Garnett was in a measure

indebted to Dr. Johnstone, the then resident physician in Moffat, for his

opinions on the uses and powers of the Hartfell water, as the reader will

doubtless perceive, by our quoting the statement of the latter. Johnstone

says, "I have known many instances of its particular good effects in coughs

proceeding from phlegm, spitting of blood, and sweatings, in stomach

complaints attended with headache; giddiness, heartburn, vomiting,

indigestion, flatulency, &c.; in gouty complaints affecting the stomach and

bowels, and in diseases peculiar to the fair sex. It has likewise been used

with great advantages in tetterous complaints and old obstinate ulcers."

This, we presume, is too palpable to bear further comment. To allow the

reader again to see the difference between the analysis of Drs. Garnett and

Thomson, we subjoin that of the latters:-

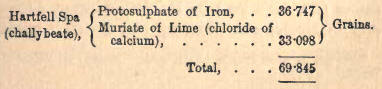

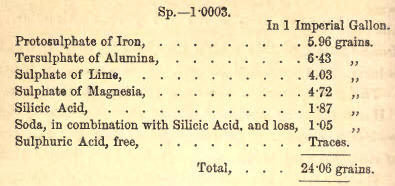

The following is Dr. Macadam's analysis:—

He accounts for the dissimilarity in results by saying

that "it is most likely referable to differences in our processes than to

great alterations in the mineral water." And now to analyse the capabilities

of this water for transmission abroad. Talking of this, Macadam says—"On

testing the contents of two bottles out of many of the Spa water, which had

been carefully corked and scaled at different periods, varying from three

weeks to a month before examination, not a trace of protosulphate of iron

was found present in either. This was decided on by there being no blue

solution formed on adding a solution of red prussiate of potash to the

mineral water. This is a ready method for anyone satisfying himself of the

value of the water. The bottles of water examined, and in which no iron in

the state of protosulphate exists, were handed to Mr. Keddie, and the author

(Dr. Macadam) by Mr. Hetherington, Apothecary in Moffat, and taken by him

from his general stock of the water as kept on sale, and their contents were

tested in his presence. The water was acid to the taste from sulphuric acid,

and somewhat astringent from Ihe sulphate of Alumina which is retained in

solution, but its chalybeate character was gone.....

The permanency of

the chalybeate character of the "Hartfell" has therefore been greatly

over-rated, and we date the period of its deterioration from the moment of

its being collected at the spring."

Though the water of this spring is of little value,

still it tended to increase the reputation of Moffat as a watering place.

The crushing reports of recent analysts regarding its over-estimated

efficacy, and the fact of its extreme distance from the town, caused it to

be seldom resorted to. This neglect, however, only commenced some years

since, for when Garnett and others proclaimed it to be the panacea for all

human ills, it was taken by many, but it failed to effect such "marvellous"

cures as its elder sister the sulphurous spring. The almost unsurpassed

beauty of the district in which the well is situated attracts numerous

visitors, and being in such close proximity to the well, curiosity leads

them personally to investigate the strength of the water. The stretch of

country seen from the heights of the Haxtfell range of mountains is a great

inducement to the tourist, who, while gazing on the varied scene lying below

and around him, the dark and grim gullies, the foaming cataracts, and the

murky and rocky shades of Haxtfell, will instinctively give utterance to the

lines of Words-worth—

"Lot

the fields, the dwindled meadows;

What a vast abyss is there!

Lo, the

clouds, the solemn shadows,

And the gli8tenings, heav'nly fair!

And

the record of commotion

Which a hundred ridges yield—

Rocks, and

gulfs, and distant ocean

Gleaming like a silver shield!"

Let us now look at the position and progress of the

town, more especially in the matter of building. However much a visit from

the inexorable rentcollector may be dreaded by parties frequently faulty in

payment, the visit of the Laird is viewed with almost universal

satisfaction, his tenants never considering that he is the cause of the

actions of the factor, by them denominated "harsh." This excitement prevails

more in provincial towns; and when the presence of the Laird is made known,

many eagerly rush to gain an envied acknowledgment from him. Thus, it is not

to be wondered at that, when in 1751 John, Earl of Hopetoun, then the

possessor of the Annandale Estates, built for himself a mansion within the

town for his occasional residence, the inhabitants were on the qui i,ire, as

they naturally supposed that greater interest would be taken in them, from

the fact of his occasiopally living in their midst. Moffat House—an

old-fashioned building, three storeys in height, and built of the stone

peculiar to the district—is the property of Mr Hope Johnstone, having

descended to him from his mother, Lady Anne, to whom it was bequeathed by

the Earl of Hopetoun, her father, who died without male heirs. Anxious to

add importance to the town, some respected natives have claimed the

existence of a Castle, or peel-house, on the site of Moffat House. These

parties have evidently recognised the danger of meddling with old

manuscripts, and considered investigation unnecessary. They have been

arrogant enough to affirm that. Moffat was at one time 'protected by some

rude fortress, but have failed to prove its existence to the satisfaction of

the public generally, and we can scarcely fancy to the satisfaction of

themselves. Till the building of Moffat House, the ground it occupies was

bare, and a view could be obtained from that point, without the obstruction

of any building whatever, to the river Annan.

About the year 1768, a number of the dwelling houses

in the town, estimated at above a hundred, belonged in property to George,

last Marquis of Annandale, and were rented by the inhabitants from him.

Those houses for the most part were taken down, while the position they

occupied was indicated by its being fenced in, and subsequently built upon,

allowing it almost to bear the exact general aspect the town has at present,

as far as the principal street (High Street) is concerned. Had a sketch been

taken of Moffat exactly a hundred years ago (1771), it would have presented

the same features, as regards the main street, as it has at present, with

the exception of a bowling green, situated in the centre of the street,

which is now non-eat, having been removed in the year 1827, to make room for

the erection of the present set of Baths, opposite which it stood. In 1791,

although slight building operations were commenced, all the houses were

inhabited, and it was with difficulty that the necessities of its population

regarding accommodation were met, far loss the demands of strangers who

signified a desire to dwell within its peaceful bowers for a specified

period. At this date, however, there were few who could with impunity be

termed "poverty stricken," all appeared to have enough, and to spare, and

consequently there were only ten persons who were actually "living on the

parish," or in other words receiving alms from the parish funds.

Irrespective of its pastoral beauties, Moffat was well

adapted for a market town from its convenient situation, and the amble land

of vast dimensions which surrounds it. Hence, shortly after the Charter of

1662 conferred on it the privilege of regality and right of markets to be

held within its bounds, we find markets springing into considerable size and

repute, and the amount realized from such of no insignificant value. The

Charter, in all its aspects, was well planned, inasmuch as every privilege

conferred upon the town ultimately became of triple value, not only in the

matter of external importance and authority, but likewise in the matter of

pecuniary aid. Moffat is emphatically termed the market town of Upper

Annandale, the district containing the parishes of Moffat, Wamphray,

Kirkpatrick-Juxta, and Johnstone, indicating a population of upwards of

5000. The numbers attracted to the town on agricultural business, of

necessity caused hotel accommodation to be provided, thus supplying proper

comforts for visitors. This was a long existing and palpable defect, as,

prior to the date we allude to, it had only the small and incommodious Black

Bull Inn, rendered famous by Burns inscribing on the window pane of the same

the well-known epigram on Miss Davies—

"Ask why God made the gem so email,

An' why so huge

the granite?

Because God meant mankind should set

The greater value

on it."

The reports of

customs received from the markets vary, but always to the side which is

indicative of increasing prosperity. In 1747 the amount raised by the

Marquis of Annandale was £3 3s 6d. Although this, by denizens of a more

important burgh, may be deemed insignificant; still it must be remembered

that this ever accumulating fund was bound to prove of service to the

administrator of justice within its bounds, or in more modern times the

representatives of the inhabitants in raising some existing pecuniary drag

upon its welfare.

Trade used

its elevating power with regard to Moffat, in this the period of its first

speculation and commercial achievement. It was what a Scotchman might term

comparatively "brisk," fifty weavers ever spinning and exporting their

manufactures as a fair example of Moffatian industry; while the other

branches of trade were nobly represented. The prosperity of Moffat was at

this time chiefly owing to the exertions of strangers, in the common

acceptation of the word. Those strangers with labour and capital introduced

right systems upon which to work, and then

"Succeeded next

The birthday of invention; weak at

first,

Dull in design, and clumsy to perform."

which was destined to put the cope-stone of success on

the fabric which they had raised. Though strangers more particularly merit

the praise, still the Moffatianz deserve great credit for their share in the

concern. But we shall take more special notice of this in the chapter

bearing on the opening of the Caledonian Railway. [Moffat, at the period of

which we have been writing, consisted of about ten streets, with many lanes

running at stated intervals from them. It must be, however, remembered that

those streets were not of the size we generally see, else Moffat would truly

have been insignificant. The High Street (then existing as shown), a

cheerful and healthy one, measures three hundred yards in length, and forty

or fifty in breadth, while the number of lanes and byways have considerably

increased. The change since then, as will be shown, has indeed been

marvellous. The suburbs of the town constitute almost the largest part of

Moffat, being perhaps twice or three times as large as Moffat proper.

Formerly the houses outside of the town were exceedingly few, and at such

distances from it, that one could scarcely claim for them any consistent

connection with Moffat, a distinction probably not envied by their

respective proprietors, as no doubt they fancied seclusion, and were anxious

to keep aloof even from the infantile bustle of the pretty watering place.]

When we commenced the present work we viewed, as a

subject which would give us infinite satisfaction, that which constitutes

the remainder of the present chapter—the ecclesiastical establishment of the

town. But it was a subject which was destined to give slight remuneration

for untiring exertions to gain definite ideas of Moffat's position thus

viewed. Though unwilling to anathematize the worthy enstodiers of those

documents which we were anxious to secure and eagerly scrutinize, still we

can scarcely refrain from raising our feeble voice against the apparent

injustice of consigning documents, important to particular individuals such

as ourselves, to rot and ruin, without their services being obtained to

unravel the complicated mass of mysteries which are the frequent possessions

of the historian. The greatest portion of those documents, which would have

materially assisted us in the consideration of such a subject as this, is

buried (for such we may truly denominate it) in the hidden recesses of

venerable and scholastic institutions, to which access is not readily gained

in the prosecution of antiquarian research and inquiry. While —infandum

renovare dolorem --- some years since many valuable documents, bearing

specially on this subject, were in a somewhat serious conflagration totally

destroyed. These annoyances did not, however, prevent us from gaining

information sufficient to give us an idea of the condition of the town,

viewed ecclesiastically, though the succeeding pages referring to its

religious denominations may more properly be viewed as a summary of events,

rather than a continuous narrative from the time we last incidentally

referred to its church history, which was during the reign of Charles II,

when, with other privileges, he conferred upon the Earl of Annandale the

right of patronage of the church situated within the town, and the "chaplanries"

connected with it, as formerly shown. We now purpose tracing the descent of

this right down to the' present time. The case of George, the last Marquis

of Annandale, as hinted in a preceding chapter, had become worthy of the

gravest apprehensions. "Can'st thou not minister to a mind diseased V' was a

question which doubtless fell from the lips of disconsolate Mends, with

eagerness as intense as the ideal of Shakespere is supposed to manifest, but

was one, alas! which ever received a negative reply. Their grave suspicions

were at last sadly realized, and in 1792 George breathed his last. Upon his

death the advowson of the Parish Church became the property of the Earl of

Hopetoun; and by his death in 1816 the right of presentation was invested in

the hands of J. J. Hope Johnstone, Esq. Era George, the Marquis, "shuffled

off this mortal coil," and left his titles to be matter of dispute for his

successors in property, his eyes might have fallen on a fabric erected for

the worship of God, a substantial ornament to the town, without the high

pretensions to architectural beauty which its predecessor possessed, and

given as a heritage to the inhabitants of the surrounding district. In 1790

the present Parish Church of Moffat was built, with accommodation for 1000

people. It was not, as might be supposed, erected on the site of the former

church; but through the liberality of James, Earl of Hopetoun, it was put

down on a piece of his own property 'midst old trees, which materially

intensify the solemnity of the scene. One would be apt to regret this were

it not for the fact that a remnant of the sacred edifice, which reared aloft

its head in ages passed away, is still visible, an ample illustration of the

words of "Delta "-

"How like

an image of repose it looks,

That ancient, holy, and sequestered pile;

Silence abides in each tree-shaded aisle.

* * * * *

On moss green'd pediments and tombstones gray,

And spectral silence

pointeth to decay."

The living of

the Parish may be thus stated-19 lialders equal parts of meal and barley,

and which includes £8 6s. 8d., to meet the expenses necessitated during the

communion season, and £89 59. in money. The Glebe comprises fifteen imperial

acres, at present let at £40 per annum, and this, in terms of the lease,

will continue for eleven years, but there is reserved for other purposes one

acre which surrounds the Manse. When, in 1843, Dr. Archibald Stewart was

appointed assistant and successor to the then minister of the parish—Mr.

Johnstone—the church was in a comparatively good condition. On the

translation of Dr. Stewart to a parish in Galloway, the now respected

minister of St. Andrew's, Edinburgh, succeeded him, and by his zeal and

Christian efforts kept the church in a flourishing state. The present

minister, the Rev. John Gibson M'Vicar, D.D., LLD., known not only in the

ecclesiastical world as an earnest and able expounder of the truth, but also

in the field of literature as a philosophical writer, which entitled him to

the honours which have been profusely showered upon him, succeeded to the

benefice in 1853, rendered vacant by the appointment of Mr. Stewart to St.

Andrew's, Edinburgh. * The efforts of Dr. M'Vicar have been signally

rewarded, and the crowded state of the church during the summer months

testifies to the high estimation in which he is hold alike by his own

parishioners and by those who, to gain ease and relaxation, make the town

their Bummer quarters. Byron has said of Time that it "But drags or drives

us on to die I" and although it is asserting its influence on the physical

condition of the worthy doctor, his present state does not render him

incapable of attending to his parochial duties and the fulfilment of the

more essential acts of a Christian minister. Our wish and prayer is, that he

may be long spared to occupy the position which hitherto he has filled with

efficiency.

The United

Presbyterian congregation was called into existence somewhere about the end

of last century, though the present church, remarkable for its tasteful and

elegant architecture and the prominent position which it occupies, was not

erected till 1862, causing an expenditure of about £4000. The following are

the names of the respective clergymen who have possessed the living:-

Rev. H. CAMERON.

JNO. MONTEITH.

JNO. RIDDELL.

WM. HUTTON, present minister.

In all the departments of Christian enterprise, the

congregation is nobly represented, and through the efforts of the present

pastor the church has not only retained the flushes of prosperity on its

countenance, brought into life through the instrumentality of his

predecessors, but it has visibly increased year by year; and he deserves

much merit for his indefatigable exertions to put the church even in a more

prosperous condition, and for his unremitting attention to the interests of

his flock.

The Free Church of

Moffat was erected immediately after the Secession of 1843, on a site gifted

by Peter Tod, Esq. of Riddings. The cost of the church, including all

expenditure for necessary alterations on the fabric, has been estimated at

between eight and nine hundred pounds. The Rev. Robert Kinnear, previously

minister of Tothorwald, was inducted first minister to the charge in August,

1843; and still holds the benefice in conjunction with the Rev. Kenneth

Moody Stewart, A. M., ordained colleague and successor in December, 1868.

"In addition to the equal dividend from the Sustentation Fund, there has

always been what is called a 'Supplement.' " Like the United Presbyterian

Church, however, the stipend has varied from year to year. The number of

communicants is between 360 and 380, and besides this there is a large

number of adherents, but there being no seat rents there is no known seat

holders. From March, 1870, to March, 1871, the total sum raised for various

purposes was the handsome one of £501 19s. 4d. In 185, a Manse was erected

at a cost of £600. At no period of her history was the church in a more

flourishing condition. It has two zealous Christian ministers to superintend

the administration of affairs; it has its complement of elders to assist

them; it has a large number of church members to stand by and encourage them

in their labours of love and works of faith; and a large, stedfast, and

united congregation, who for any good object readily give their pecuniary

aid. In concluding this chapter, we wish for the various religious

denominations, a continuance of that prosperity which they have hitherto

merited and received.

|