|

When Mr. Telford had occasion

to visit London on business during the early period of his career, his

quarters were at the Salopian Coffee House, now the Ship Hotel, at Charing

Cross. It is probable that his Shropshire connections led him in the first

instance to the 'Salopian;' but the situation being near to the Houses of

Parliament, and in many respects convenient for the purposes of his

business, he continued to live there for no less a period than twenty-one

years. During that time the Salopian became a favourite resort of engineers;

and not only Telford's provincial associates, but numerous visitors from

abroad (where his works attracted even more attention than they did in

England) took up their quarters there. Several apartments were specially

reserved for Telford's exclusive use, and he could always readily command

any additional accommodation for purposes of business or hospitality.

The successive landlords of

the Salopian came to regard the engineer as a fixture, and even bought and

sold him from time to time with the goodwill of the business. When he at

length resolved, on the persuasion of his friends, to take a house of his

own, and gave notice of his intention of leaving, the landlord, who had but

recently entered into possession, almost stood aghast. "What! leave the

house!" said he; "Why, Sir, I have just paid 750L. for you!" On explanation

it appeared that this price had actually been paid by him to the outgoing

landlord, on the assumption that Mr. Telford was a fixture of the hotel; the

previous tenant having paid 450L. for him; the increase in the price marking

very significantly the growing importance of the engineer's position. There

was, however, no help for the disconsolate landlord, and Telford left the

Salopian to take possession of his new house at 24, Abingdon Street. Labelye,

the engineer of Westminster Bridge, had formerly occupied the dwelling; and,

at a subsequent period, Sir William Chambers, the architect of Somerset

House, Telford used to take much pleasure in pointing out to his visitors

the painting of Westminster Bridge, impanelled in the wall over the parlour

mantelpiece, made for Labelye by an Italian artist whilst the bridge works

were in progress. In that house Telford continued to live until the close of

his life.

One of the subjects in which

he took much interest during his later years was the establishment of the

Institute of Civil Engineers. In 1818 a Society had been formed, consisting

principally of young men educated to civil and mechanical engineering, who

occasionally met to discuss matters of interest relating to their

profession. As early as the time of Smeaton, a social meeting of engineers

was occasionally held at an inn in Holborn, which was discontinued in 1792,

in consequence of some personal differences amongst the members. It was

revived in the following year, under the auspices of Mr. Jessop, Mr. Naylor,

Mr. Rennie, and Mr. Whitworth, and joined by other gentlemen of scientific

distinction. They were accustomed to dine together every fortnight at the

Crown and Anchor in the Strand, spending the evening in conversation on

engineering subjects. But as the numbers and importance of the profession

increased, the desire began to be felt, especially among the junior members

of the profession, for an institution of a more enlarged character. Hence

the movement above alluded to, which led to an invitation being given to Mr.

Telford to accept the office of President of the proposed Engineers'

Institute. To this he consented, and entered upon the duties of the office

on the 21st of March, 1820.*[1] During the remainder of his life, Mr.

Telford continued to watch over the progress of the Society, which gradually

grew in importance and usefulness. He supplied it with the nucleus of a

reference library, now become of great value to its members. He established

the practice of recording the proceedings,*[2] minutes of discussions, and

substance of the papers read, which has led to the accumulation, in the

printed records of the Institute, of a vast body of information as to

engineering practice. In 1828 he exerted himself strenuously and

successfully in obtaining a Charter of Incorporation for the Society; and

finally, at his death, he left the Institute their first bequest of 2000L.,

together with many valuable books, and a large collection of documents which

had been subservient to his own professional labours.

In the distinguished position

which he occupied, it was natural that Mr. Telford should be called upon, as

he often was, towards the close of his life, to give his opinion and advice

as to projects of public importance. Where strongly conflicting opinions

were entertained on any subject, his help was occasionally found most

valuable; for he possessed great tact and suavity of manner, which often

enabled him to reconcile opposing interests when they stood in the way of

important enterprises.

In 1828 he was appointed one

of the commissioners to investigate the subject of the supply of water to

the metropolis, in conjunction with Dr. Roget and Professor Brande, and the

result was the very able report published in that year. Only a few months

before his death, in 1834, he prepared and sent in an elaborate separate

report, containing many excellent practical suggestions, which had the

effect of stimulating the efforts of the water companies, and eventually

leading, to great improvements.

On the subject of roads,

Telford continued to be the very highest authority, his friend Southey

jocularly styling him the "Colossus of Roads." The Russian Government

frequently consulted him with reference to the new roads with which that

great empire was being opened up. The Polish road from Warsaw to Briesc, on

the Russian frontier, 120 miles in length, was constructed after his plans,

and it remains, we believe, the finest road in the Russian dominions to this

day.

Section of Polish Road

He was consulted by the

Austrian Government on the subject of bridges as well as roads. Count

Szechenyi recounts the very agreeable and instructive interview which he had

with Telford when he called to consult him as to the bridge proposed to be

erected across the Danube, between the towns of Buda and Pesth. On a

suspension bridge being suggested by the English engineer, the Count, with

surprise, asked if such an erection was possible under the circumstances he

had described? "We do not consider anything to be impossible," replied

Telford; "impossibilities exist chiefly in the prejudices of mankind, to

which some are slaves, and from which few are able to emancipate themselves

and enter on the path of truth." But supposing a suspension bridge were not

deemed advisable under the circumstances, and it were considered necessary

altogether to avoid motion, "then," said he, "I should recommend you to

erect a cast iron bridge of three spans, each 400 feet; such a bridge will

have no motion, and though half the world lay a wreck, it would still

stand."*[3] A suspension bridge was eventually resolved upon. It was

constructed by one of Mr. Telford's ablest pupils, Mr. Tierney Clark,

between the years 1839 and 1850, and is justly regarded as one of the

greatest triumphs of English engineering, the Buda-Pesth people proudly

declaring it to be "the eighth wonder of the world."

At a time when speculation

was very rife--in the year 1825-- Mr. Telford was consulted respecting a

grand scheme for cutting a canal across the Isthmus of Darien; and about the

same time he was employed to resurvey the line for a ship canal--which had

before occupied the attention of Whitworth and Rennie--between Bristol and

the English Channel. But although he gave great attention to this latter

project, and prepared numerous plans and reports upon it, and although an

Act was actually passed enabling it to be carried out, the scheme was

eventually abandoned, like the preceding ones with the same object, for want

of the requisite funds.

Our engineer had a perfect

detestation of speculative jobbing in all its forms, though on one occasion

he could not help being used as an instrument by schemers. A public company

was got up at Liverpool, in 1827, to form a broad and deep ship canal, of

about seven miles in length, from opposite Liverpool to near Helbre Isle, in

the estuary of the Dee; its object being to enable the shipping of the port

to avoid the variable shoals and sand-banks which obstruct the entrance to

the Mersey. Mr. Telford entered on the project with great zeal, and his name

was widely quoted in its support. It appeared, however, that one of its

principal promoters, who had secured the right of pre-emption of the land on

which the only possible entrance to the canal could be formed on the

northern side, suddenly closed with the corporation of Liverpool, who were

opposed to the plan, and "sold", his partners as well as the engineer for a

large sum of money. Telford, disgusted at being made the instrument of an

apparent fraud upon the public, destroyed all the documents relating to the

scheme, and never afterwards spoke of it except in terms of extreme

indignation.

About the same time, the

formation of locomotive railways was extensively discussed, and schemes were

set on foot to construct them between several of the larger towns. But Mr.

Telford was now about seventy years old; and, desirous of limiting the range

of his business rather than extending it, he declined to enter upon this new

branch of engineering. Yet, in his younger days, he had surveyed numerous

lines of railway--amongst others, one as early as the year 1805, from

Glasgow to Berwick, down the vale of the Tweed. A line from

Newcastle-on-Tyne to Carlisle was also surveyed and reported on by him some

years later; and the Stratford and Moreton Railway was actually constructed

under his direction. He made use of railways in all his large works of

masonry, for the purpose of facilitating the haulage of materials to the

points at which they were required to be deposited or used. There is a paper

of his on the Inland Navigation of the County of Salop, contained in 'The

Agricultural Survey of Shropshire,' in which he speaks of the judicious use

of railways, and recommends that in all future surveys "it be an instruction

to the engineers that they do examine the county with a view of introducing

iron railways wherever difficulties may occur with regard to the making of

navigable canals." When the project of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

was started, we are informed that he was offered the appointment of

engineer; but he declined, partly because of his advanced age, but also out

of a feeling of duty to his employers, the Canal Companies, stating that he

could not lend his name to a scheme which, if carried out, must so

materially affect their interests.

Towards the close of his

life, he was afflicted by deafness, which made him feel exceedingly

uncomfortable in mixed society. Thanks to a healthy constitution, unimpaired

by excess and invigorated by active occupation, his working powers had

lasted longer than those of most men. He was still cheerful, clear-headed,

and skilful in the arts of his profession, and felt the same pleasure in

useful work that he had ever done. It was, therefore, with difficulty that

he could reconcile himself to the idea of retiring from the field of

honourable labour, which he had so long occupied, into a state of

comparative inactivity. But he was not a man who could be idle, and he

determined, like his great predecessor Smeaton, to occupy the remaining

years of his life in arranging his engineering papers for publication.

Vigorous though he had been, he felt that the time was shortly approaching

when the wheels of life must stand still altogether. Writing to a friend at

Langholm, he said, "Having now being occupied for about seventy-five years

in incessant exertion, I have for some time past arranged to decline the

contest; but the numerous works in which I am engaged have hitherto

prevented my succeeding. In the mean time I occasionally amuse myself with

setting down in what manner a long life has been laboriously, and I hope

usefully, employed." And again, a little later, he writes: "During the last

twelve months I have had several rubs; at seventy-seven they tell more

seriously than formerly, and call for less exertion and require greater

precautions. I fancy that few of my age belonging to the valley of the Esk

remain in the land of the living."*[4]

One of the last works on

which Mr. Telford was professionally consulted was at the instance of the

Duke of Wellington--not many years younger than himself, but of equally

vigorous intellectual powers--as to the improvement of Dover Harbour, then

falling rapidly to decay. The long-continued south-westerly gales of 1833-4

had the effect of rolling an immense quantity of shingle up Channel towards

that port, at the entrance to which it became deposited in unusual

quantities, so as to render it at times altogether inaccessible. The Duke,

as a military man, took a more than ordinary interest in the improvement of

Dover, as the military and naval station nearest to the French coast; and it

fell to him as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports to watch over the

preservation of the harbour, situated at a point in the English Channel

which he regarded as of great strategic importance in the event of a

continental war. He therefore desired Mr. Telford to visit the place and

give his opinion as to the most advisable mode of procedure with a view to

improving the harbour. The result was a report, in which the engineer

recommended a plan of sluicing, similar to that adopted by Mr. Smeaton at

Ramsgate, which was afterwards carried out with considerable success by Mr.

James Walker, C.E.

This was his last piece of

professional work. A few months later he was laid up by bilious derangement

of a serious character, which recurred with increased violence towards the

close of the year; and on the 2nd of September, 1834, Thomas Telford closed

his useful and honoured career, at the advanced age of seventy-seven. With

that absence of ostentation which characterised him through life, he

directed that his remains should be laid, without ceremony, in the burial

ground of the parish church of St. Margaret's, Westminster. But the members

of the Institute of Civil Engineers, who justly deemed him their benefactor

and chief ornament, urged upon his executors the propriety of interring him

in Westminster Abbey.

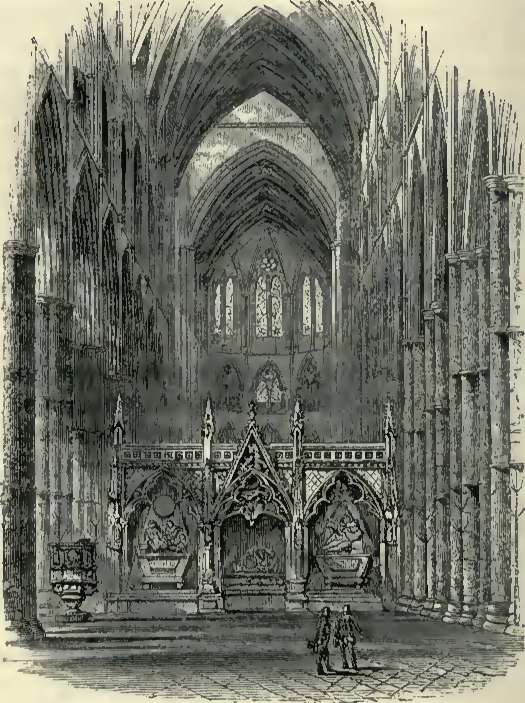

Telford's Burial Place in Westminster Abbey

He was buried there

accordingly, near the middle of the nave; where the letters, "Thomas

Telford, 1834, mark the place beneath which he lies.*[5] The adjoining stone

bears the inscription, "Robert Stephenson, 1859," that engineer having

during his life expressed the wish that his body should be laid near that of

Telford; and the son of the Killingworth engineman thus sleeps by the side

of the son of the Eskdale shepherd.

It was a long, a successful,

and a useful life which thus ended. Every step in his upward career, from

the poor peasant's hut in Eskdale to Westminster Abbey, was nobly and

valorously won. The man was diligent and conscientious; whether as a working

mason hewing stone blocks at Somerset House, as a foreman of builders at

Portsmouth, as a road surveyor at Shrewsbury, or as an engineer of bridges,

canals, docks, and harbours. The success which followed his efforts was

thoroughly well-deserved. He was laborious, pains-taking, and skilful; but,

what was better, he was honest and upright. He was a most reliable man; and

hence he came to be extensively trusted. Whatever he undertook, he

endeavoured to excel in. He would be a first-rate hewer, and he became one.

He was himself accustomed to attribute much of his success to the thorough

way in which he had mastered the humble beginnings of this trade. He was

even of opinion that the course of manual training he had undergone, and the

drudgery, as some would call it, of daily labour --first as an apprentice,

and afterwards as a journeyman mason-- had been of greater service to him

than if he had passed through the curriculum of a University.

Writing to his friend, Miss

Malcolm, respecting a young man who desired to enter the engineering

profession, he in the first place endeavoured to dissuade the lady from

encouraging the ambition of her protege, the profession being overstocked,

and offering very few prizes in proportion to the large number of blanks.

"But," he added, "if civil engineering, notwithstanding these

discouragements, is still preferred, I may point out that the way in which

both Mr. Rennie and myself proceeded, was to serve a regular apprenticeship

to some practical employment--he to a millwright, and I to a general

house-builder. In this way we secured the means, by hard labour, of earning

a subsistence; and, in time, we obtained by good conduct the confidence of

our employers and the public; eventually rising into the rank of what is

called Civil Engineering. This is the true way of acquiring practical skill,

a thorough knowledge of the materials employed in construction, and last,

but not least, a perfect knowledge of the habits and dispositions of the

workmen who carry out our designs. This course, although forbidding to many

a young person, who believes it possible to find a short and rapid path to

distinction, is proved to be otherwise by the two examples I have cited. For

my own part, I may truly aver that 'steep is the ascent, and slippery is the

way.'"*[6] That Mr. Telford was enabled to continue to so advanced an age

employed on laborious and anxious work, was no doubt attributable in a great

measure to the cheerfulness of his nature. He was, indeed, a most

happy-minded man. It will be remembered that, when a boy, he had been known

in his valley as "Laughing Tam." The same disposition continued to

characterise him in his old age. He was playful and jocular, and rejoiced in

the society of children and young people, especially when well-informed and

modest. But when they pretended to acquirements they did not possess, he was

quick to detect and see through them. One day a youth expatiated to him in

very large terms about a friend of his, who had done this and that, and made

so and so, and could do all manner of wonderful things. Telford listened

with great attention, and when the youth had done - he quietly asked, with a

twinkle in his eye, "Pray, can your friend lay eggs?"

When in society he gave

himself up to it, and thoroughly enjoyed it. He did not sit apart, a moody

and abstracted "lion;" nor desire to be regarded as "the great engineer,"

pondering new Menai Bridges; But he appeared in his natural character of a

simple, intelligent, cheerful companion; as ready to laugh at his own jokes

as at other people's; and he was as communicative to a child as to any

philosopher of the party.

Robert Southey, than whom

there was no better judge of a loveable man, said of him, "I would go a long

way for the sake of seeing Telford and spending a few days in his company."

Southey, as we have seen, had the best opportunities of knowing him well;

for a long journey together extending over many weeks, is, probably, better

than anything else, calculated to bring out the weak as well as the strong

points of a friend: indeed, many friendships have completely broken down

under the severe test of a single week's tour. But Southey on that occasion

firmly cemented a friendship which lasted until Telford's death. On one

occasion the latter called at the poet's house, in company with Sir Henry

Parnell, when engaged upon the survey of one of his northern roads.

Unhappily Southey was absent at the time; and, writing about the

circumstance to a correspondent, he said, "This was a mortification to me,

in as much as I owe Telford every kind of friendly attention, and like him

heartily."

Campbell, the poet, was

another early friend of our engineer; and the attachment seems to have been

mutual. Writing to Dr. Currie, of Liverpool, in 1802, Campbell says: "I have

become acquainted with Telford the engineer, 'a fellow of infinite humour,'

and of strong enterprising mind. He has almost made me a bridge-builder

already; at least he has inspired me with new sensations of interest in the

improvement and ornament of our country. Have you seen his plan of London

Bridge? or his scheme for a new canal in the North Highlands, which will

unite, if put in effect, our Eastern and Atlantic commerce, and render

Scotland the very emporium of navigation? Telford is a most useful cicerone

in London. He is so universally acquainted, and so popular in his manners,

that he can introduce one to all kinds of novelty, and all descriptions of

interesting society." Shortly after, Campbell named his first son after

Telford, who stood godfather for the boy. Indeed, for many years, Telford

played the part of Mentor to the young and impulsive poet, advising him

about his course in life, trying to keep him steady, and holding him aloof

as much as possible from the seductive allurements of the capital. But it

was a difficult task, and Telford's numerous engagements necessarily left

the poet at many seasons very much to himself. It appears that they were

living together at the Salopian when Campbell composed the first draft of

his poem of Hohenlinden; and several important emendations made in it by

Telford were adopted by Campbell. Although the two friends pursued different

roads in life, and for many years saw little of each other, they often met

again, especially after Telford took up his abode at his house in Abingdon

Street, where Campbell was a frequent and always a welcome guest.

When engaged upon his

surveys, our engineer was the same simple, cheerful, laborious man. While at

work, he gave his whole mind to the subject in hand, thinking of nothing

else for the time; dismissing it at the close of each day's work, but ready

to take it up afresh with the next day's duties. This was a great advantage

to him as respected the prolongation of his working faculty. He did not take

his anxieties to bed with him, as many do, and rise up with them in the

morning; but he laid down the load at the end of each day, and resumed it

all the more cheerfully when refreshed and invigorated by natural rest, It

was only while the engrossing anxieties connected with the suspension of the

chains of Menai Bridge were weighing heavily upon his mind, that he could

not sleep; and then, age having stolen upon him, he felt the strain almost

more than he could bear. But that great anxiety once fairly over, his

spirits speedily resumed their wonted elasticity.

When engaged upon the

construction of the Carlisle and Glasgow road, he was very fond of getting a

few of the "navvy men," as he called them, to join him at an ordinary at the

Hamilton Arms Hotel, Lanarkshire, each paying his own expenses. On such

occasions Telford would say that, though he could not drink, yet he would

carve and draw corks for them. One of the rules he laid down was that no

business was to be introduced from the moment they sat down to dinner. All

at once, from being the plodding, hard-working engineer, with responsibility

and thought in every feature, Telford unbended and relaxed, and became the

merriest and drollest of the party. He possessed a great fund of anecdote

available for such occasions, had an extraordinary memory for facts relating

to persons and families, and the wonder to many of his auditors was, how in

all the world a man living in London should know so much better about their

locality and many of its oddities than they did themselves.

In his leisure hours at home,

which were but few, he occupied himself a good deal in the perusal of

miscellaneous literature, never losing his taste for poetry. He continued to

indulge in the occasional composition of verses until a comparatively late

period of his life; one of his most successful efforts being a translation

of the 'Ode to May,' from Buchanan's Latin poems, executed in a very tender

and graceful manner. That he might be enabled to peruse engineering works in

French and German, he prosecuted the study of those languages, and with such

success that he was shortly able to read them with comparative ease. He

occasionally occupied himself in literary composition on subjects connected

with his profession. Thus he wrote for the Edinburgh Encyclopedia, conducted

by his friend Sir David (then Dr.) Brewster, the elaborate and able articles

on Architecture, Bridge-building, and Canal-making. Besides his

contributions to that work, he advanced a considerable sum of money to aid

in its publication, which remained a debt due to his estate at the period of

his death.

Notwithstanding the pains

that Telford took in the course of his life to acquire a knowledge of the

elements of natural science, it is somewhat remarkable to find him holding;

acquirements in mathematics so cheap. But probably this is to be accounted

for by the circumstance of his education being entirely practical, and

mainly self-acquired. When a young man was on one occasion recommended to

him as a pupil because of his proficiency in mathematics, the engineer

expressed the opinion that such acquirements were no recommendation. Like

Smeaton, he held that deductions drawn from theory were never to be trusted;

and he placed his reliance mainly on observation, experience, and

carefully-conducted experiments. He was also, like most men of strong

practical sagacity, quick in mother wit, and arrived rapidly at conclusions,

guided by a sort of intellectual instinct which can neither be defined nor

described.*[7] Although occupied as a leading engineer for nearly forty

years-- having certified contractors' bills during that time amounting to

several millions sterling--he died in comparatively moderate circumstances.

Eminent constructive ability was not very highly remunerated in Telford's

time, and he was satisfied with a rate of pay which even the smallest "M. I.

C. E." would now refuse to accept. Telford's charges were, however, perhaps

too low; and a deputation of members of the profession on one occasion

formally expostulated with him on the subject.

Although he could not be said

to have an indifference for money, he yet estimated it as a thing worth

infinitely less than character; and every penny that he earned was honestly

come by. He had no wife, *[8] nor family, nor near relations to provide

for,--only himself in his old age. Not being thought rich, he was saved the

annoyance of being haunted by toadies or pestered by parasites. His wants

were few, and his household expenses small; and though he entertained many

visitors and friends, it was in a quiet way and on a moderate scale. The

small regard he had for personal dignity may be inferred from the fact, that

to the last he continued the practice, which he had learnt when a working

mason, of darning his own stockings.*[9]

Telford nevertheless had the

highest idea of the dignity of his profession; not because of the money it

would produce, but of the great things it was calculated to accomplish. In

his most confidential letters we find him often expatiating on the noble

works he was engaged in designing or constructing, and the national good

they were calculated to produce, but never on the pecuniary advantages he

himself was to derive from them. He doubtless prized, and prized highly, the

reputation they would bring him; and, above all, there seemed to be

uppermost in his mind, especially in the earlier part of his career, while

many of his schoolfellows were still alive, the thought of "What will they

say of this in Eskdale?" but as for the money results to himself, Telford

seemed, to the close of his life, to regard them as of comparatively small

moment.

During the twenty-one years

that he acted as principal engineer for the Caledonian Canal, we find from

the Parliamentary returns that the amount paid to him for his reports,

detailed plans, and superintendence, was exactly 237L. a year. Where he

conceived any works to be of great public importance, and he found them to

be promoted by public-spirited persons at their own expense, he refused to

receive any payment for his labour, or even repayment of the expenses

incurred by him. Thus, while employed by the Government in the improvement

of the Highland roads, he persuaded himself that he ought at the same time

to promote the similar patriotic objects of the British Fisheries Society,

which were carried out by voluntary subscription; and for many years he

acted as their engineer, refusing to accept any remuneration whatever for

his trouble.*[10]

Telford held the sordid

money-grubber in perfect detestation. He was of opinion that the adulation

paid to mere money was one of the greatest dangers with which modern society

was threatened. "I admire commercial enterprise," he would say; "it is the

vigorous outgrowth of our industrial life: I admire everything that gives it

free scope:, as, wherever it goes, activity, energy, intelligence-- all that

we call civilization--accompany it; but I hold that the aim and end of all

ought not to be a mere bag, of money, but something far higher and far

better."

Writing once to his Langholm

correspondent about an old schoolfellow, who had grown rich by scraping,

Telford said: "Poor Bob L---- His industry and sagacity were more than

counterbalanced by his childish vanity and silly avarice, which rendered his

friendship dangerous, and his conversation tiresome. He was like a man in

London, whose lips, while walking by himself along the streets, were

constantly ejaculating 'Money! Money!' But peace to Bob's memory: I need

scarcely add, confusion to his thousands!" Telford was himself most careful

in resisting the temptations to which men in his position are frequently

exposed; but he was preserved by his honest pride, not less than by the

purity of his character. He invariably refused to receive anything in the

shape of presents or testimonials from persons employed under him. He would

not have even the shadow of an obligation stand in the way of his duty to

those who employed him to watch over and protect their interests. During the

many years that he was employed on public works, no one could ever charge

him in the remotest degree with entering into a collusion with contractors.

He looked upon such arrangements as degrading and infamous, and considered

that they meant nothing less than an inducement to "scamping," which he

would never tolerate.

His inspection of work was

most rigid. The security of his structures was not a question of money, but

of character. As human life depended upon their stability, not a point was

neglected that could ensure it. Hence, in his selection of resident

engineers and inspectors of works, he exercised the greatest possible

precautions; and here his observation of character proved of essential

value. Mr. Hughes says he never allowed any but his most experienced and

confidential assistants to have anything to do with exploring the

foundations of buildings he was about to erect. His scrutiny into the

qualifications of those employed about such structures extended to the

subordinate overseers, and even to the workmen, insomuch that men whose

general habits had before passed unnoticed, and whose characters had never

been inquired into, did not escape his observation when set to work in

operations connected with foundations.*[11] If he detected a man who gave

evidences of unsteadiness, inaccuracy, or carelessness, he would reprimand

the overseer for employing such a person, and order him to be removed to

some other part of the undertaking where his negligence could do no harm.

And thus it was that Telford put his own character, through those whom he

employed, into the various buildings which he was employed to construct.

But though Telford was

comparatively indifferent about money, he was not without a proper regard

for it, as a means of conferring benefits on others, and especially as a

means of being independent. At the close of his life he had accumulated as

much as, invested at interest, brought him in about 800L. a year, and

enabled him to occupy the house in Abingdon Street in which he died. This

was amply sufficient for his wants, and more than enough for his

independence. It enabled him also to continue those secret acts of

benevolence which constituted perhaps the most genuine pleasure of his life.

It is one of the most delightful traits in this excellent man's career to

find him so constantly occupied in works of spontaneous charity, in quarters

so remote and unknown that it is impossible the slightest feeling of

ostentation could have sullied the purity of the acts. Among the large mass

of Telford's private letters which have been submitted to us, we find

frequent reference to sums of money transmitted for the support of poor

people in his native valley. At new year's time he regularly sent

remittances of from 30L. to 50L., to be distributed by the kind Miss Malcolm

of Burnfoot, and, after her death, by Mr. Little, the postmaster at Langholm;

and the contributions thus so kindly made, did much to fend off the winter's

cold, and surround with many small comforts those who most needed help, but

were perhaps too modest to ask it.*[12]

Many of those in the valley

of the Esk had known of Telford in his younger years as a poor barefooted

boy; though now become a man of distinction, he had too much good sense to

be ashamed of his humble origin; perhaps he even felt proud that, by dint of

his own valorous and persevering efforts, he had been able to rise so much

above it. Throughout his long life, his heart always warmed at the thought

of Eskdale. He rejoiced at the honourable rise of Eskdale men as reflecting

credit upon his "beloved valley." Thus, writing to his Langholm

correspondent with reference to the honours conferred on the different

members of the family of Malcolm, he said: "The distinctions so deservedly

bestowed upon the Burnfoot family, establish a splendid era in Eskdale; and

almost tempt your correspondent to sport his Swedish honours, which that

grateful country has repeatedly, in spite of refusal, transmitted."

It might be said that there

was narrowness and provincialism in this; But when young men are thrown into

the world, with all its temptations and snares, it is well that the

recollections of home and kindred should survive to hold them in the path of

rectitude, and cheer them in their onward and upward course in life. And

there is no doubt that Telford was borne up on many occasions by the thought

of what the folks in the valley would say about him and his progress in

life, when they met together at market, or at the Westerkirk porch on

Sabbath mornings. In this light, provincialism or local patriotism is a

prolific source of good, and may be regarded as among the most valuable and

beautiful emanations of the parish life of our country. Although Telford was

honoured with the titles and orders of merit conferred upon him by foreign

monarchs, what he esteemed beyond them all was the respect and gratitude of

his own countrymen; and, not least, the honour which his really noble and

beneficent career was calculated to reflect upon "the folks of the nook,"

the remote inhabitants of his native Eskdale.

When the engineer proceeded

to dispose of his savings by will, which he did a few months before his

death, the distribution was a comparatively easy matter. The total amount of

his bequeathments was 16,600L.*[13] About one-fourth of the whole he set

apart for educational purposes, --2000L. to the Civil Engineers' Institute,

and 1000L. each to the ministers of Langholm and Westerkirk, in trust for

the parish libraries. The rest was bequeathed, in sums of from 200L. to

500L., to different persons who had acted as clerks, assistants, and

surveyors, in his various public works; and to his intimate personal

friends. Amongst these latter were Colonel Pasley, the nephew of his early

benefactor; Mr. Rickman, Mr. Milne, and Mr. Hope, his three executors; and

Robert Southey and Thomas Campbell, the poets. To both of these last the

gift was most welcome. Southey said of his: "Mr. Telford has most kindly and

unexpectedly left me 500L., with a share of his residuary property, which I

am told will make it amount in all to 850L. This is truly a godsend, and I

am most grateful for it. It gives me the comfortable knowledge that, if it

should please God soon to take me from this world, my family would have

resources fully sufficient for their support till such time as their affairs

could be put in order, and the proceeds of my books, remains, &c., be

rendered available. I have never been anxious overmuch, nor ever taken more

thought for the morrow than it is the duty of every one to take who has to

earn his livelihood; but to be thus provided for at this time I feel to be

an especial blessing.'"*[14] Among the most valuable results of Telford's

bequests in his own district, was the establishment of the popular libraries

at Langholm and Westerkirk, each of which now contains about 4000 volumes.

That at Westerkirk had been originally instituted in the year 1792, by the

miners employed to work an antimony mine (since abandoned) on the farm of

Glendinning, within sight of the place where Telford was born. On the

dissolution of the mining company, in 1800, the little collection of books

was removed to Kirkton Hill; but on receipt of Telford's bequest, a special

building was erected for their reception at Old Bentpath near the village of

Westerkirk. The annual income derived from the Telford fund enabled

additions of new volumes to be made to it from time to time; and its uses as

a public institution were thus greatly increased. The books are exchanged

once a month, on the day of the full moon; on which occasion readers of all

ages and conditions,--farmers, shepherds, ploughmen, labourers, and their

children,--resort to it from far and near, taking away with them as many

volumes as they desire for the month's readings.

Thus there is scarcely a

cottage in the valley in which good books are not to be found under perusal;

and we are told that it is a common thing for the Eskdale shepherd to take a

book in his plaid to the hill-side--a volume of Shakespeare, Prescott, or

Macaulay-- and read it there, under the blue sky, with his sheep and the

green hills before him. And thus, so long as the bequest lasts, the good,

great engineer will not cease to be remembered with gratitude in his beloved

Eskdale.

Footnotes for Chapter XV.

*[1] In his inaugural address

to the members on taking the chair, the President pointed out that the

principles of the Institution rested on the practical efforts and unceasing

perseverance of the members themselves. "In foreign countries," he said,

"similar establishments are instituted by government, and their members and

proceedings are under their control; but here, a different course being

adopted, it becomes incumbent on each individual member to feel that the

very existence and prosperity of the Institution depend, in no small degree,

on his personal conduct and exertions; and my merely mentioning the

circumstance will, I am convinced, be sufficient to command the best efforts

of the present and future members."

*[2] We are informed by

Joseph Mitchell, Esq., C.E., of the origin of this practice. Mr. Mitchell

was a pupil of Mr. Telford's, living with him in his house at 24, Abingdon

Street. It was the engineer's custom to have a dinner party every Tuesday,

after which his engineering friends were invited to accompany him to the

Institution, the meetings of which were then held on Tuesday evenings in a

house in Buckingham Street, Strand. The meetings did not usually consist of

more than from twenty to thirty persons. Mr. Mitchell took notes of the

conversations which followed the reading of the papers. Mr. Telford

afterwards found his pupil extending the notes, on which he asked permission

to read them, and was so much pleased that he took them to the next meeting

and read them to the members. Mr. Mitchell was then formally appointed

reporter of conversations to the Institute; and the custom having been

continued, a large mass of valuable practical information has thus been

placed on record.

*[3] Supplement to Weale's

'Bridges,' Count Szechenyi's Report, p. 18.

*[4] Letter to Mrs. Little,

Langholm, 28th August, 1833.

*[5] A statue of him, by

Bailey, has since been placed in the east aisle of the north transept, known

as the Islip Chapel. It is considered a fine work, but its effect is quite

lost in consequence of the crowded state of the aisle, which has very much

the look of a sculptor's workshop. The subscription raised for the purpose

of erecting the statue was 1000L., of which 200L. was paid to the Dean for

permission to place it within the Abbey.

*[6] Letter to Miss Malcolm,

Burnfoot, Langholm, dated 7th October, 1830.

*[7] Sir David Brewster,

observes on this point: "It is difficult to analyse that peculiar faculty of

mind which directs a successful engineer who is not guided by the deductions

of the exact sciences; but it must consist mainly in the power of observing

the effects of natural causes acting in a variety of circumstances; and in

the judicious application of this knowledge to cases when the same causes

come into operation. But while this sagacity is a prominent feature in the

designs of Mr. Telford, it appears no less distinctly in the choice of the

men by whom they were to be practically executed. His quick perception of

character, his honesty of purpose, and his contempt for all

otheracquirements,-- save that practical knowledge and experience which was

best fitted to accomplish, in the best manner, the object he had in

view,--have enables him to leave behind him works of inestimable value, and

monuments of professional celebrity which have not been surpassed either in

Britain or in Europe."--'Edinburgh Review,' vol. lxx. p. 46.

*[8] It seems singular that

with Telford's great natural powers of pleasing, his warm social

temperament, and his capability of forming ardent attachments for friends,

many of them women, he should never have formed an attachment of the heart.

Even in his youthful and poetical days, the subject of love, so frequently

the theme of boyish song, is never alluded to; while his school friendships

are often recalled to mind and, indeed, made the special subject of his

verse. It seems odd to find him, when at Shrewsbury--a handsome fellow, with

a good position, and many beautiful women about him--addressing his friend,

the blind schoolmaster at Langholm, as his "Stella"!

*[9] Mr. Mitchell says: "He

lived at the rate of about 1200L. a year. He kept a carriage, but no horses,

and used his carriage principally for making his journeys through the

country on business. I once accompanied him to Bath and Cornwall, when he

made me keep an accurate journal of all I saw. He used to lecture us on

being independent, even in little matters, and not ask servants to do for us

what we might easily do for ourselves. He carried in his pocket a small book

containing needles, thread, and buttons, and on an emergency was always

ready to put in a stitch. A curious habit he had of mending his stockings,

which I suppose he acquired when a working mason. He would not permit his

housekeeper to touch them, but after his work at night, about nine or half

past, he would go up stairs, and take down a lot, and sit mending them with

great apparent delight in his own room till bed-time. I have frequently gone

in to him with some message, and found him occupied with this work."

*[10] "The British Fisheries

Society," adds Mr. Rickman, "did not suffer themselves to be entirely

outdone in liberality, and shortly before his death they pressed upon Mr.

Telford a very handsome gift of plate, which, being inscribed with

expressions of their thankfulness and gratitude towards him, he could not

possibly refuse to accept."--'Life of Telford,' p. 283.

*[11] Weale's 'Theory.

Practice, and Architecture of Bridges,' vol.i.: 'Essay on Foundations of

Bridges,' by T. Hughes, C.E., p. 33.

*[12] Letter to Mr. William

Little, Langholm, 24th January, 1815.

*[13] Telford thought so

little about money, that he did not even know the amount he died possessed

of. It turned out that instead of 16,600L. it was about 30,000L.; so that

his legatees had their bequests nearly doubled. For many years he had

abstained from drawing the dividends on the shares which he held in the

canals and other public companies in which he was concerned. At the money

panic of 1825, it was found that he had a considerable sum lying in the

hands of his London bankers at little or no interest, and it was only on the

urgent recommendation of his friend, Sir P. Malcolm, that he invested it in

government securities, then very low.

*[14] 'Selections from the

Letters of Robert Southey,' vol. iv., p. 391. We may here mention that the

last article which Southey wrote for the 'Quarterly' was his review of the '

Life of Telford.' |