|

It will have been observed,

from the preceding narrative, how much had already been accomplished by

skill and industry towards opening up the material resources of the kingdom.

The stages of improvement which we have recorded indeed exhibit a measure of

the vital energy which has from time to time existed in the nation. In the

earlier periods of engineering history, the war of man was with nature. The

sea was held back by embankments. The Thames, instead of being allowed to

overspread the wide marshes on either bank, was confined within limited

bounds, by which the navigable depth of its channel was increased, at the

same time that a wide extent of land was rendered available for agriculture.

In those early days, the

great object was to render the land more habitable, comfortable, and

productive. Marshes were reclaimed, and wastes subdued. But so long as the

country remained comparatively closed against communication, and intercourse

was restricted by the want of bridges and roads, improvement was extremely

slow. For, while roads are the consequence of civilisation, they are also

among its most influential causes. We have seen even the blind Metcalf

acting as an effective instrument of progress in the northern counties by

the formation of long lines of road. Brindley and the Duke of Bridgewater

carried on the work in the same districts, and conferred upon the north and

north-west of England the blessings of cheap and effective water

communication. Smeaton followed and carried out similar undertakings in

still remoter places, joining the east and west coasts of Scotland by the

Forth and Clyde Canal, and building bridges in the far north. Rennie made

harbours, built bridges, and hewed out docks for shipping, the increase in

which had kept pace with the growth of our home and foreign trade. He was

followed by Telford, whose long and busy life, as we have seen, was occupied

in building bridges and making roads in all directions, in districts of the

country formerly inaccessible, and therefore comparatively barbarous. At

length the wildest districts of the Highlands and the most rugged mountain

valleys of North Wales were rendered as easy of access as the comparatively

level counties in the immediate neighbourhood of the metropolis.

During all this while, the

wealth and industry of the country had been advancing with rapid strides.

London had grown in population and importance. Many improvements had been

effected in the river, But the dock accommodation was still found

insufficient; and, as the recognised head of his profession, Mr. Telford,

though now grown old and fast becoming infirm, was called upon to supply the

requisite plans. He had been engaged upon great works for upwards of thirty

years, previous to which he had led the life of a working mason. But he had

been a steady, temperate man all his life; and though nearly seventy, when

consulted as to the proposed new docks, his mind was as able to deal with

the subject in all its bearings as it had ever been; and he undertook the

work.

In 1824 a new Company was

formed to provide a dock nearer to the heart of the City than any of the

existing ones. The site selected was the space between the Tower and the

London Docks, which included the property of St. Katherine's Hospital. The

whole extent of land available was only twenty-seven acres of a very

irregular figure, so that when the quays and warehouses were laid out, it

was found that only about ten acres remained for the docks; but these, from

the nature of the ground, presented an unusual amount of quay room. The

necessary Act was obtained in 1825; the works were begun in the following

year; and on the 25th of October, 1828, the new docks were completed and

opened for business.

The St. Katherine Docks

communicate with the river by means of an entrance tide-lock, 180 feet long

and 45 feet wide, with three pairs of gates, admitting either one very large

or two small vessels at a time. The lock-entrance and the sills under the

two middle lock-gates were fixed at the depth of ten feet under the level of

low water of ordinary spring tides. The formation of these dock-entrances

was a work of much difficulty, demanding great skill on the part of the

engineer. It was necessary to excavate the ground to a great depth below low

water for the purpose of getting in the foundations, and the cofferdams were

therefore of great strength, to enable them, when pumped out by the

steam-engine, to resist the lateral pressure of forty feet of water at high

tide. The difficulty was, however, effectually overcome, and the wharf

walls, locks, sills and bridges of the St. Katherine Docks are generally

regarded as a master-piece of harbour construction. Alluding to the rapidity

with which the works were completed, Mr. Telford says: "Seldom, indeed never

within my knowledge, has there been an instance of an undertaking; of this

magnitude, in a very confined situation, having been perfected in so short a

time;.... but, as a practical engineer, responsible for the success of

difficult operations, I must be allowed to protest against such haste,

pregnant as it was, and ever will be, with risks, which, in more instances

than one, severely taxed all my experience and skill, and dangerously

involved the reputation of the directors as well as of their engineer."

Among the remaining bridges

executed by Mr. Telford, towards the close of his professional career, may

be mentioned those of Tewkesbury and Gloucester. The former town is situated

on the Severn at its confluence with the river Avon, about eleven miles

above Gloucester. The surrounding district was rich and populous; but being

intersected by a large river, without a bridge, the inhabitants applied to

Parliament for powers to provide so necessary a convenience. The design

first proposed by a local architect was a bridge of three arches; but Mr.

Telford, when called upon to advise the trustees, recommended that, in order

to interrupt the navigation as little as possible, the river should be

spanned by a single arch; and he submitted a design of such a character,

which was approved and subsequently erected. It was finished and opened in

April, 1826.

This is one of the largest as

well as most graceful of Mr. Telford's numerous cast iron bridges. It has a

single span of 170 feet, with a rise of only 17 feet, consisting of six ribs

of about three feet three inches deep, the spandrels being filled in with

light diagonal work. The narrow Gothic arches in the masonry of the

abutments give the bridge a very light and graceful appearance, at the same

time that they afford an enlarged passage for the high river floods.

The bridge at Gloucester

consists of one large stone arch of 150 feet span. It replaced a structure

of great antiquity, of eight arches, which had stood for about 600 years.

The roadway over it was very narrow, and the number of piers in the river

and the small dimensions of the arches offered considerable obstruction to

the navigation. To give the largest amount of waterway, and at the same time

reduce the gradient of the road over the bridge to the greatest extent, Mr.

Telford adopted the following expedient. He made the general body of the

arch an ellipse, 150 feet on the chord-line and 35 feet rise, while the

voussoirs, or external archstones, being in the form of a segment, have the

same chord, with only 13 feet rise. "This complex form," says Mr. Telford,

"converts each side of the vault of the arch into the shape of the entrance

of a pipe, to suit the contracted passage of a fluid, thus lessening the

flat surface opposed to the current of the river whenever the tide or upland

flood rises above the springing of the middle of the ellipse, that being at

four feet above low water; whereas the flood of 1770 rose twenty feet above

low water of an ordinary spring-tide, which, when there is no upland flood,

rises only eight or nine feet."*[1] The bridge was finished and opened in

1828.

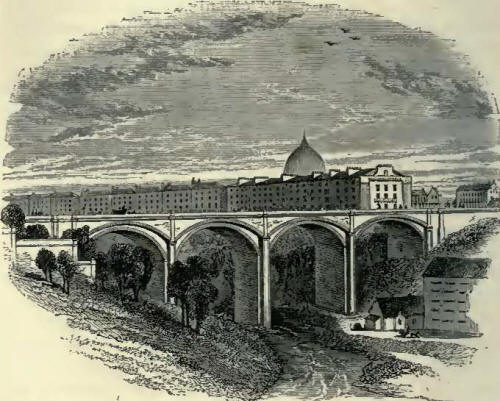

Dean Bridge, Edinburgh.

The last structures erected

after our engineer's designs were at Edinburgh and Glasgow: his Dean Bridge

at the former place, and his Jamaica Street Bridge at the latter, being

regarded as among his most successful works. Since his employment as a

journeyman mason at the building of the houses in Princes Street, Edinburgh,

the New Town had spread in all directions. At each visit to it on his way to

or from the Caledonian Canal or the northern harbours, he had been no less

surprised than delighted at the architectural improvements which he found

going forward. A new quarter had risen up during his lifetime, and had

extended northward and westward in long lines of magnificent buildings of

freestone, until in 1829 its further progress was checked by the deep ravine

running along the back of the New Town, in the bottom of which runs the

little Water of Leith. It was determined to throw a stone bridge across this

stream, and Telford was called upon to supply the design. The point of

crossing the valley was immediately behind Moray Place, which stands almost

upon its verge, the sides being bold, rocky, and finely wooded. The

situation was well adapted for a picturesque structure, such as Telford was

well able to supply. The depth of the ravine to be spanned involved great

height in the piers, the roadway being 106 feet above the level of the

stream. The bridge was of four arches of 90 feet span each, and its total

length 447 feet; the breadth between the parapets for the purposes of the

roadway and footpaths being 39 feet.*[2] It was completed and opened in

December, 1831.

But the most important, as it

was the last, of Mr. Telford's stone bridges was that erected across the

Clyde at the Broomielaw, Glasgow. Little more than fifty years since, the

banks of the river at that place were literally covered with broom--and

hence its name--while the stream was scarcely deep enough to float a

herring-buss. Now, the Broomielaw is a quay frequented by ships of the

largest burden, and bustling with trade and commerce. Skill and enterprise

have deepened the Clyde, dredged away its shoals, built quays and wharves

along its banks, and rendered it one of the busiest streams in the world,

It has become a great river

thoroughfare, worked by steam. On its waters the first steamboat ever

constructed for purposes of traffic in Europe was launched by Henry Bell in

1812; and the Clyde boats to this day enjoy the highest prestige.

The deepening of the river at

the Broomielaw had led to a gradual undermining of the foundations of the

old bridge, which was situated close to the principal landing-place. A

little above it, was an ancient overfall weir, which had also contributed to

scour away the foundations of the piers. Besides, the bridge was felt to be

narrow, inconvenient, and ill-adapted for accommodating the immense traffic

passing across the Clyde at that point. It was, therefore, determined to

take down the old structure, and Build a new one; and Mr. Telford was called

upon to supply the design. The foundation was laid with great ceremony on

the 18th of March, 1833, and the new bridge was completed and opened on the

1st of January, 1836, rather more than a year after the engineer's death. It

is a very fine work, consisting of seven arches, segments of circles, the

central arch being 58 feet 6 inches; the span of the adjoining arches

diminishing to 57 feet 9 inches, 55 feet 6 inches, and 52 feet respectively.

It is 560 feet in length, with an open waterway of 389 feet, and its total

width of carriageway and footpath is 60 feet, or wider, at the time it was

built, than any river bridge in the kingdom.

Glasgow Bridge

Like most previous engineers

of eminence--like Perry, Brindley, Smeaton, and Rennie--Mr. Telford was in

the course of his life extensively employed in the drainage of the Fen

districts. He had been jointly concerned with Mr. Rennie in carrying out the

important works of the Eau Brink Cut, and at Mr. Rennie's death he succeeded

to much of his practice as consulting engineer.

It was principally in

designing and carrying out the drainage of the North Level that Mr. Telford

distinguished himself in Fen drainage. The North Level includes all that

part of the Great Bedford Level situated between Morton's Leam and the river

Welland, comprising about 48,000 acres of land. The river Nene, which brings

down from the interior the rainfall of almost the entire county of

Northampton, flows through nearly the centre of the district. In some places

the stream is confined by embankments, in others it flows along artificial

outs, until it enters the great estuary of the Wash, about five miles below

Wisbeach. This town is situated on another river which flows through the

Level, called the Old Nene. Below the point of junction of these rivers with

the Wash, and still more to seaward, was South Holland Sluice, through which

the waters of the South Holland Drain entered the estuary. At that point a

great mass of silt had accumulated, which tended to choke up the mouths of

the rivers further inland, rendering their navigation difficult and

precarious, and seriously interrupting the drainage of the whole lowland

district traversed by both the Old and New Nene. Indeed the sands were

accumulating at such a rate, that the outfall of the Wisbeach River

threatened to become completely destroyed.

Such being the state of

things, it was determined to take the opinion of some eminent engineer, and

Mr. Rennie was employed to survey the district and recommend a measure for

the remedy of these great evils. He performed this service in his usually

careful and masterly manner; but as the method which he proposed, complete

though it was, would have seriously interfered with the trade of Wisbeach,

by leaving it out of the line of navigation and drainage which he proposed

to open up, the corporation of that town determined to employ another

engineer; and Mr Telford was selected to examine and report upon the whole

subject, keeping in view the improvement of the river immediately adjacent

to the town of Wisbeach.

Mr. Telford confirmed Mr.

Rennie's views to a large extent, more especially with reference to the

construction of an entirely new outfall, by making an artificial channel

from Kindersleys Cut to Crab-Hole Eye anchorage, by which a level lower by

nearly twelve feet would be secured for the outfall waters; but he preferred

leaving the river open to the tide as high as Wisbeach, rather than place a

lock with draw-doors at Lutton Leam Sluice, as had been proposed by Mr.

Rennie. He also suggested that the acute angle at the Horseshoe be cut off

and the river deepened up to the bridge at Wisbeach, making a new cut along

the bank on the south side of the town, which should join the river again

immediately above it, thereby converting the intermediate space, by

draw-doors and the usual contrivances, into a floating dock. Though this

plan was approved by the parties interested in the drainage, to Telford's

great mortification it was opposed by the corporation of Wisbeach, and like

so many other excellent schemes for the improvement of the Fen districts, it

eventually fell to the ground.

The cutting of a new outfall

for the river Nene, however, could not much longer be delayed without great

danger to the reclaimed lands of the North Level, which, but for some relief

of the kind, must shortly have become submerged and reduced to their

original waste condition. The subject was revived in 1822, and Mr. Telford

was again called upon, in conjunction with Sir John Rennie, whose father had

died in the preceding year, to submit a plan of a new Nene Outfall; but it

was not until the year 1827 that the necessary Act was obtained, and then

only with great difficulty and cost, in consequence of the opposition of the

town of Wisbeach. The works consisted principally of a deep cut or canal,

about six miles in length, penetrating far through the sand banks into the

deep waters of the Wash. They were begun in 1828, and brought to completion

in 1830, with the most satisfactory results. A greatly improved outfall was

secured by thus carrying. the mouths of the rivers out to sea, and the

drainage of the important agricultural districts through which the Nene

flows was greatly benefited; while at the same time nearly 6000 acres of

valuable corn-growing land were added to the county of Lincoln.

But the opening of the Nene

Outfall was only the first of a series of improvements which eventually

included the whole of the valuable lands of the North Level, in the district

situated between the Nene and the Welland. The opening at Gunthorpe Sluice,

which was the outfall for the waters of the Holland Drain, was not less than

eleven feet three inches above low water at Crab-Hole; and it was therefore

obvious that by lowering this opening a vastly improved drainage of the

whole of the level district, extending from twenty to thirty miles inland,

for which that sluice was the artificial outlet, would immediately be

secured. Urged by Mr. Telford, an Act for the purpose of carrying out the

requisite improvement was obtained in 1830, and the excavations having been

begun shortly after, were completed in 1834.

A new cut was made from

Clow's Cross to Gunthorpe Sluice, in place of the winding course of the old

Shire Drain; besides which, a bridge was erected at Cross Keys, or Sutton

Wash, and an embankment was made across the Salt Marshes, forming a high

road, which, with the bridges previously erected at Fossdyke and Lynn,

effectually connected the counties of Norfolk and Lincoln. The result of the

improved outfall was what the engineer had predicted. A thorough natural

drainage was secured for an extensive district, embracing nearly a hundred

thousand acres of fertile land, which had before been very ineffectually

though expensively cleared of the surplus water by means of windmills and

steam-engines. The productiveness of the soil was greatly increased, and the

health and comfort of the inhabitants promoted to an extent that surpassed

all previous expectation.

The whole of the new cuts

were easily navigable, being from 140 to 200 feet wide at bottom, whereas

the old outlets had been variable and were often choked with shifting sand.

The district was thus effectually opened up for navigation, and a convenient

transit afforded for coals and other articles of consumption. Wisbeach

became accessible to vessels of much larger burden, and in the course of a

few years after the construction of the Nene Outfall, the trade of the port

had more than doubled. Mr. Telford himself, towards the close of his life,

spoke with natural pride of the improvements which he had thus been in so

great a measure instrumental in carrying out, and which had so materially

promoted the comfort, prosperity, and welfare of a very extensive

district.*[3]

We may mention, as a

remarkable effect of the opening of the new outfall, that in a few hours the

lowering of the waters was felt throughout the whole of the Fen level. The

sluggish and stagnant drains, cuts, and leams in far distant places, began

actually to flow; and the sensation created was such, that at Thorney, near

Peterborough, some fifteen miles from the sea, the intelligence penetrated

even to the congregation then sitting in church--for it was Sunday

morning--that "the waters were running!" when immediately the whole flocked

out, parson and all, to see the great sight, and acknowledge the

lessings of science. A humble Fen poet of the last century thus quaintly

predicted the moral results likely to arise from the improved drainage of

his native district:-

"With a change of elements

suddenly

There shall a change of men and manners be;

Hearts thick and tough as hides shall feel remorse,

And souls of sedge shall understand discourse;

New hands shall learn to work, forget to steal,

New legs shall go to church, new knees to kneel."

The prophecy has indeed been

fulfilled. The barbarous race of Fen-men has disappeared before the skill of

the engineer. As the land has been drained, the half-starved fowlers and

fen-roamers have subsided into the ranks of steady industry--become farmers,

traders, and labourers. The plough has passed over the bed of Holland Fen,

and the agriculturist reaps his increase more than a hundred fold.. Wide

watery wastes, formerly abounding in fish, are now covered with waving crops

of corn every summer. Sheep graze on the dry bottom of Whittlesea Mere, and

kine low where not many years since the silence of the waste was only

disturbed by the croaking of frogs and the screaming of wild fowl. All this

has been the result of the science of the engineer, the enterprise of the

landowner, and the industry of our peaceful army of skilled labourers.*[4]

Footnotes for Chapter XIII.

*[1] Telford's Life, p261

*[2] The piers are built

internally with hollow compartments, as at the Menai Bridge, the side walls

being 3 feet thick and the cross walls 2 feet. Projecting from the piers and

abutments are pilasters of solid masonry. The main arches have their

springing 70 feet from the foundations and rise 30 feet; and at 20 feet

higher, other arches, of 96 feet span and 10 feet rise, are constructed; the

face of these, projecting before the main arches and spandrels, producing a

distinct external soffit of 5 feet in breadth. This, with the peculiar

piers, constitutes the principal distinctive feature in the, bridge.

*[3] "The Nene Outfall

channel," says Mr. Tycho Wing, "was projected by the late Mr. Rennie in

1814, and executed jointly by Mr. Telford and the present Sir John Rennie.

But the scheme of the North Level Drainage was eminently the work of Mr.

Telford, and was undertaken upon his advice and responsibility, when only a

few persons engaged in the Nene Outfall believed that the latter could be

made, or if made, that it could be maintained. Mr. Telford distinguished

himself by his foresight and judicious counsels at the most critical periods

of that great measure, by his unfailing confidence in its success, and by

the boldness and sagacity which prompted him to advise the making of the

North Level drainage, in full expectation of the results for the sake of

which the Nene Outfall was undertaken, and which are now realised to the

extent of the most sanguine hopes."

*[4] Now that the land

actually won has been made so richly productive, the engineer is at work

with magnificent schemes of reclamation of lands at present submerged by the

sea. The Norfolk Estuary Company have a scheme for reclaiming 50,000 acres;

the Lincolnshire Estuary Company, 30,000 acres; and the Victoria Level

Company, 150,000 acres--all from the estuary of the Wash. By the process

called warping, the land is steadily advancing upon the ocean, and before

many years have passed, thousands of acres of the Victoria Level will have

been reclaimed for purposes of agriculture. |