|

Mr. Telford's extensive

practice as a bridge-builder led his friend Southey to designate him "Pontifex

Maximus." Besides the numerous bridges erected by him in the West of

England, we have found him furnishing designs for about twelve hundred in

the Highlands, of various dimensions, some of stone and others of iron. His

practice in bridge-building had, therefore, been of an unusually extensive

character, and Southey's sobriquet was not ill applied. But besides being a

great bridge-builder, Telford was also a great road-maker. With the progress

of industry and trade, the easy and rapid transit of persons and goods had

come to be regarded as an increasing object of public interest. Fast coaches

now ran regularly between all the principal towns of England; every effort

being made, by straightening and shortening the roads, cutting down hills,

and carrying embankments across valleys and viaducts over rivers, to render

travelling by the main routes as easy and expeditious as possible.

Attention was especially

turned to the improvement of the longer routes, and to perfecting the

connection of London with the chief town's of Scotland and Ireland. Telford

was early called upon to advise as to the repairs of the road between

Carlisle and Glasgow, which had been allowed to fall into a wretched state;

as well as the formation of a new line from Carlisle, across the counties of

Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, and Wigton, to Port Patrick, for the purpose of

ensuring a more rapid communication with Belfast and the northern parts of

Ireland. Although Glasgow had become a place of considerable wealth and

importance, the roads to it, north of Carlisle, continued in a very

unsatisfactory state. It was only in July, 1788, that the first mail-coach

from London had driven into Glasgow by that route, when it was welcomed by a

procession of the citizens on horseback, who went out several miles to meet

it. But the road had been shockingly made, and before long had become almost

impassable. Robert Owen states that, in 1795, it took him two days and three

nights' incessant travelling to get from Manchester to Glasgow, and he

mentions that the coach had to cross a well-known dangerous mountain at

midnight, called Erickstane Brae, which was then always passed with fear and

trembling.*[1] As late as the year 1814 we find a Parliamentary Committee

declaring the road between Carlisle and Glasgow to be in so ruinous a state

as often seriously to delay the mail and endanger the lives of travellers.

The bridge over Evan Water was so much decayed, that one day the coach and

horses fell through it into the river, when "one passenger was killed, the

coachman survived only a few days, and several other persons were dreadfully

maimed; two of the horses being also killed."*[2] The remaining part of the

bridge continued for some time unrepaired, just space enough being left for

a single carriage to pass. The road trustees seemed to be helpless, and did

nothing; a local subscription was tried and failed, the district passed

through being very poor; but as the road was absolutely required for more

than merely local purposes, it was eventually determined to undertake its

reconstruction as a work of national importance, and 50,000L. was granted by

Parliament with this object, under the provisions of the Act passed in 1816.

The works were placed under Mr. Telford's charge; and an admirable road was

very shortly under construction between Carlisle and Glasgow. That part of

it between Hamilton and Glasgow, eleven miles in length, was however left in

the hands of local trustees, as was the diversion of thirteen miles at the

boundary of the counties of Lanark and Dumfries, for which a previous Act

had been obtained. The length of new line constructed by Mr. Telford was

sixty-nine miles, and it was probably the finest piece of road which up to

that time had been made.

His ordinary method of

road-making in the Highlands was, first to level and drain; then, like the

Romans, to lay a solid pavement of large stones, the round or broad end

downwards, as close as they could be set. The points of the latter were then

broken off, and a layer of stones broken to about the size of walnuts, was

laid upon them, and over all a little gravel if at hand. A road thus formed

soon became bound together, and for ordinary purposes was very durable.

But where the traffic, as in

the case of the Carlisle and Glasgow road, was expected to be very heavy,

Telford took much greater pains. Here he paid especial attention to two

points: first, to lay it out as nearly as possible upon a level, so as to

reduce the draught to horses dragging heavy vehicles,--one in thirty being

about the severest gradient at any part of the road. The next point was to

make the working, or middle portion of the road, as firm and substantial as

possible, so as to bear, without shrinking, the heaviest weight likely to be

brought over it. With this object he specified that the metal bed was to be

formed in two layers, rising about four inches towards the centre the bottom

course being of stones (whinstone, limestone, or hard freestone), seven

inches in depth. These were to be carefully set by hand, with the broadest

ends downwards, all crossbonded or jointed, no stone being more than three

inches wide on the top. The spaces between them were then to be filled up

with smaller stones, packed by hand, so as to bring the whole to an even and

firm surface. Over this a top course was to be laid, seven inches in depth,

consisting of properly broken hard whinstones, none exceeding six ounces in

weight, and each to be able to pass through a circular ring, two inches and

a half in diameter; a binding of gravel, about an inch in thickness, being

placed over all. A drain crossed under the bed of the bottom layer to the

outside ditch in every hundred yards. The result was an admirably easy,

firm, and dry road, capable of being travelled upon in all weathers, and

standing in comparatively small need of repairs.

A similar practice was

introduced in England about the same time by Mr. Macadam; and, though his

method was not so thorough as that of Telford, it was usefully employed on

most of the high roads throughout the kingdom. Mr. Macadam's notice was

first called to the subject while acting as one of the trustees of a road in

Ayrshire. Afterwards, while employed as Government agent for victualling the

navy in the western parts of England, he continued the study of road-making,

keeping in view the essential conditions of a compact and durable substance

and a smooth surface. At that time the attention of the Legislature was not

so much directed to the proper making and mending of the roads, as to

suiting the vehicles to them such as they were; and they legislated

backwards and forwards for nearly half a century as to the breadth of

wheels. Macadam was, on the other hand, of opinion that the main point was

to attend to the nature of the roads on which the vehicles were to travel.

Most roads were then made with gravel, or flints tumbled upon them in their

natural state, and so rounded that they had no points of contact, and rarely

became consolidated. When a heavy vehicle of any sort passed over them,

their loose structure presented no resistance; the material was thus

completely disturbed, and they often became almost impassable. Macadam's

practice was this: to break the stones into angular fragments, so that a bed

several inches in depth should be formed, the material best adapted for the

purpose being fragments of granite, greenstone, or basalt; to watch the

repairs of the road carefully during the process of consolidation, filling

up the inequalities caused by the traffic passing over it, until a hard and

level surface had been obtained. Thus made, the road would last for years

without further attention. in 1815 Mr. Macadam devoted himself with great

enthusiasm to road-making as a profession, and being appointed

surveyor-general of the Bristol roads, he had full opportunities of

exemplifying his system. It proved so successful that the example set by him

was quickly followed over the entire kingdom. Even the streets of many large

towns were Macadamised. In carrying out his improvements, however, Mr.

Macadam spent several thousand pounds of his own money, and in 1825, having

proved this expenditure before a Committee of the House of Commons, the

amount was reimbursed to him, together with an honorary tribute of two

thousand pounds. Mr. Macadam died poor, but, as he himself said, "a least an

honest man." By his indefatigable exertions and his success as a road-maker,

by greatly saving animal labour, facilitating commercial intercourse, and

rendering travelling easy and expeditious, he entitled himself to the

reputation of a public benefactor.

J. L. Macadam.

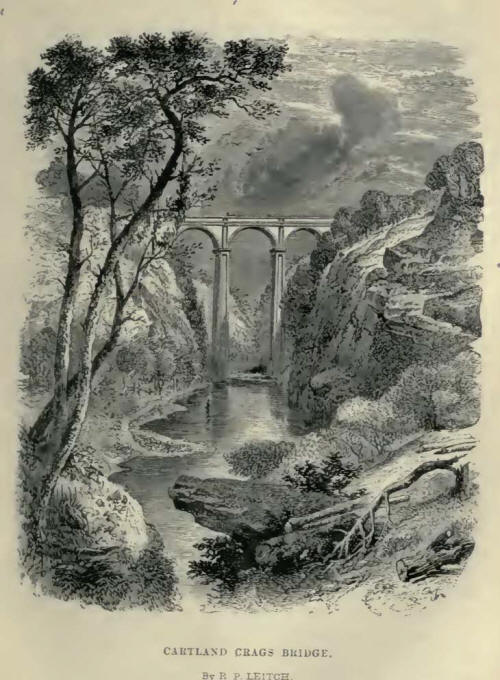

Owing to the mountainous

nature of the country through which Telford's Carlisle and Glasgow road

passes, the bridges are unusually numerous and of large dimensions. Thus,

the Fiddler's Burn Bridge is of three arches, one of 150 and two of 105 feet

span each. There are fourteen other bridges, presenting from one to three

arches, of from 20 to 90 feet span. But the most picturesque and remarkable

bridge constructed by Telford in that district was upon another line of road

subsequently carried out by him, in the upper part of the county of Lanark,

and crossing the main line of the Carlisle and Glasgow road almost at right

angles. Its northern and eastern part formed a direct line of communication

between the great cattle markets of Falkirk, Crief, and Doune, and Carlisle

and the West of England. It was carried over deep ravines by several lofty

bridges, the most formidable of which was that across the Mouse Water at

Cartland Crags, about a mile to the west of Lanark. The stream here flows

through a deep rocky chasm, the sides of which are in some places about four

hundred feet high. At a point where the height of the rocks is considerably

less, but still most formidable, Telford spanned the ravine with the

beautiful bridge represented in the engraving facing this page, its parapet

being 129 feet above the surface of the water beneath.

Cartland Crags Bridge.

The reconstruction of the

western road from Carlisle to Glasgow, which Telford had thus satisfactorily

carried out, shortly led to similar demands from the population on the

eastern side of the kingdom. The spirit of road reform was now fairly on

foot. Fast coaches and wheel-carriages of all kinds had become greatly

improved, so that the usual rate of travelling had advanced from five or six

to nine or ten miles an hour. The desire for the rapid communication of

political and commercial intelligence was found to increase with the

facilities for supplying it; and, urged by the public wants, the Post-Office

authorities were stimulated to unusual efforts in this direction. Numerous

surveys were made and roads laid out, so as to improve the main line of

communication between London and Edinburgh and the intermediate towns. The

first part of this road taken in hand was the worst--that lying to the north

of Catterick Bridge, in Yorkshire. A new line was surveyed by West Auckland

to Hexham, passing over Garter Fell to Jedburgh, and thence to Edinburgh;

but was rejected as too crooked and uneven. Another was tried by Aldstone

Moor and Bewcastle, and rejected for the same reason. The third line

proposed was eventually adopted as the best, passing from Morpeth, by Wooler

and Coldstream, to Edinburgh; saving rather more than fourteen miles between

the two points, and securing a line of road of much more favourable

gradients.

The principal bridge on this

new highway was at Pathhead, over the Tyne, about eleven miles south of

Edinburgh. To maintain the level, so as to avoid the winding of the road

down a steep descent on one side of the valley and up an equally steep

ascent on the other, Telford ran out a lofty embankment from both sides,

connecting their ends by means of a spacious bridge. The structure at

Pathhead is of five arches, each 50 feet span, with 25 feet rise from their

springing, 49 feet above the bed of the river. Bridges of a similar

character were also thrown over the deep ravines of Cranston Dean and Cotty

Burn, in the same neighbourhood. At the same time a useful bridge was built

on the same line of road at Morpeth, in Northumberland, over the river

Wansbeck. It consisted of three arches, of which the centre one was 50 feet

span, and two side-arches 40 feet each; the breadth between the parapets

being 30 feet.

The advantages derived from

the construction of these new roads were found to be so great, that it was

proposed to do the like for the remainder of the line between London and

Edinburgh; and at the instance of the Post-Office authorities, with the

sanction of the Treasury, Mr. Telford proceeded to make detailed surveys of

an entire new post-road between London and Morpeth. In laying it out, the

main points which he endeavoured to secure were directness and flatness; and

100 miles of the proposed new Great North Road, south of York, were laid out

in a perfectly straight line. This survey, which was begun in 1824, extended

over several years; and all the requisite arrangements had been made for

beginning the works, when the result of the locomotive competition at

Rainhill, in 1829, had the effect of directing attention to that new method

of travelling, fortunately in time to prevent what would have proved, for

the most part, an unnecessary expenditure, on works soon to be superseded by

a totally different order of things.

The most important

road-improvements actually carried out under Mr. Telford's immediate

superintendence were those on the western side of the island, with the

object of shortening the distance and facilitating the communication between

London and Dublin by way of Holyhead, as well as between London and

Liverpool. At the time of the Union, the mode of transit between the capital

of Ireland and the metropolis of the United Kingdom was tedious, difficult,

and full of peril. In crossing the Irish Sea to Liverpool, the packets were

frequently tossed about for days together. On the Irish side, there was

scarcely the pretence of a port, the landing-place being within the bar of

the river Liffey, inconvenient at all times, and in rough weather extremely

dangerous. To avoid the long voyage to Liverpool, the passage began to be

made from Dublin to Holyhead, the nearest point of the Welsh coast. Arrived

there, the passengers were landed upon rugged, unprotected rocks, without a

pier or landing convenience of any kind.*[3] But the traveller's perils were

not at an end,--comparatively speaking they had only begun. From Holyhead,

across the island of Anglesea, there was no made road, but only a miserable

track, circuitous and craggy, full of terrible jolts, round bogs and over

rocks, for a distance of twenty-four miles. Having reached the Menai Strait,

the passengers had again to take to an open ferry-boat before they could

gain the mainland. The tide ran with great rapidity through the Strait, and,

when the wind blew strong, the boat was liable to be driven far up or down

the channel, and was sometimes swamped altogether. The perils of the Welsh

roads had next to be encountered, and these were in as bad a condition at

the beginning of the present century as those of the Highlands above

described. Through North Wales they were rough, narrow, steep, and

unprotected, mostly unfenced, and in winter almost impassable. The whole

traffic on the road between Shrewsbury and Bangor was conveyed by a small

cart, which passed between the two places once a week in summer. As an

illustration of the state of the roads in South Wales, which were quite as

bad as those in the North, we may state that, in 1803, when the late Lord

Sudeley took home his bride from the neighbourhood of Welshpool to his

residence only thirteen miles distant, the carriage in which the newly

married pair rode stuck in a quagmire, and the occupants, having extricated

themselves from their perilous situation, performed the rest of their

journey on foot.

The first step taken was to

improve the landing-places on both the Irish and Welsh sides of St. George's

Channel, and for this purpose Mr. Rennie was employed in 1801. The result

was, that Howth on the one coast, and Holyhead on the other, were fixed upon

as the most eligible sites for packet stations. Improvements, however,

proceeded slowly, and it was not until 1810 that a sum of 10,000L. was

granted by Parliament to enable the necessary works to be begun. Attention

was then turned to the state of the roads, and here Mr. Telford's services

were called into requisition. As early as 1808 it had been determined by the

Post-Office authorities to put on a mail-coach between Shrewsbury and

Holyhead; but it was pointed out that the roads in North Wales were so rough

and dangerous that it was doubtful whether the service could be conducted

with safety. Attempts were made to enforce the law with reference to their

repair, and no less than twenty-one townships were indicted by the

Postmaster-General. The route was found too perilous even for a riding post,

the legs of three horses having been broken in one week.*[4] The road across

Anglesea was quite as bad. Sir Henry Parnell mentioned, in 1819, that the

coach had been overturned beyond Gwynder, going down one of the hills, when

a friend of his was thrown a considerable distance from the roof into a pool

of water. Near the post-office of Gwynder, the coachman had been thrown from

his seat by a violent jolt, and broken his leg. The post-coach, and also the

mail, had been overturned at the bottom of Penmyndd Hill; and the route was

so dangerous that the London coachmen, who had been brought down to "work"

the country, refused to continue the duty because of its excessive dangers.

Of course, anything like a regular mail-service through such a district was

altogether impracticable.

The indictments of the

townships proved of no use; the localities were too poor to provide the

means required to construct a line of road sufficient for the conveyance of

mails and passengers between England and Ireland. The work was really a

national one, to be carried out at the national cost. How was this best to

be done? Telford recommended that the old road between Shrewsbury and

Holyhead (109 miles long) should be shortened by about four miles, and made

as nearly as possible on a level; the new line proceeding from Shrewsbury by

Llangollen, Corwen, Bettws-y-Coed, Capel-Curig, and Bangor, to Holyhead. Mr.

Telford also proposed to cross the Menai Strait by means of a cast iron

bridge, hereafter to be described.

Although a complete survey

was made in 1811, nothing was done for several years. The mail-coaches

continued to be overturned, and stage-coaches, in the tourist season, to

break down as before.*[5] The Irish mail-coach took forty one hours to reach

Holyhead from the time of its setting out from St. Martin's-le-Grand; the

journey was performed at the rate of only 6 3/4 miles an hour, the mail

arriving in Dublin on the third day. The Irish members made many complaints

of the delay and dangers to which they were exposed in travelling up to

town. But, although there was much discussion, no money was voted until the

year 1815, when Sir Henry Parnell vigorously took the question in hand and

successfully carried it through. A Board of Parliamentary Commissioners was

appointed, of which he was chairman, and, under their direction, the new

Shrewsbury and Holyhead road was at length commenced and carried to

completion, the works extending over a period of about fifteen years. The

same Commissioners excrcised an authority over the roads between London and

Shrewsbury; and numerous improvements were also made in the main line at

various points, with the object of facilitating communication between London

and Liverpool as well as between London and Dublin.

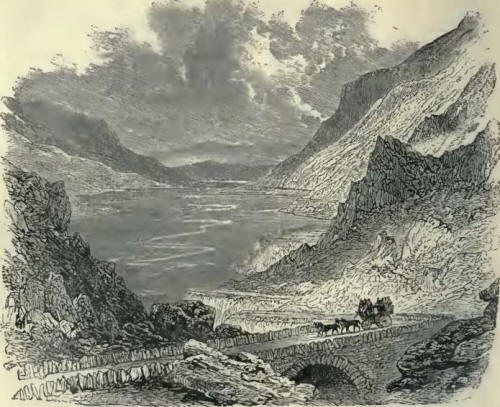

The rugged nature of the

country through which the new road passed, along the slopes of rocky

precipices and across inlets of the sea, rendered it necessary to build many

bridges, to form many embankments, and cut away long stretches of rock, in

order to secure an easy and commodious route. The line of the valley of the

Dee, to the west of Llangollen, was selected, the road proceeding along the

scarped sides of the mountains, crossing from point to point by lofty

embankments where necessary; and, taking into account the character of the

country, it must be acknowledged that a wonderfully level road was secured.

While the gradients on the old road had in some cases been as steep as 1 in

6 1/2, passing along the edge of unprotected precipices, the new one was so

laid out as to be no more than 1 in 20 at any part, while it was wide and

well protected along its whole extent. Mr. Telford pursued the same system

that he had adopted in the formation of the Carlisle and Glasgow road, as

regards metalling, cross-draining, and fence-walling; for the latter purpose

using schistus, or slate rubble-work, instead of sandstone. The largest

bridges were of iron; that at Bettws-y-Coed, over the Conway--called the

Waterloo Bridge, constructed in 1815--being a very fine specimen of

Telford's iron bridge-work.

Those parts of the road which

had been the most dangerous were taken in hand first, and, by the year 1819,

the route had been rendered comparatively commodious and safe. Angles were

cut off, the sides of hills were blasted away, and several heavy embankments

run out across formidable arms of the sea. Thus, at Stanley Sands, near

Holyhead, an embankment was formed 1300 yards long and 16 feet high, with a

width of 34 feet at the top, along which the road was laid. Its breadth at

the base was 114 feet, and both sides were coated with rubble stones, as a

protection against storms. By the adoption of this expedient, a mile and a

half was saved in a distance of six miles. Heavy embankments were also run

out, where bridges were thrown across chasms and ravines, to maintain the

general level. From Ty-Gwynn to Lake Ogwen, the road along the face of the

rugged hill and across the river Ogwen was entirely new made, of a uniform

width of 28 feet between the parapets, with an inclination of only 1 in 22

in the steepest place. A bridge was thrown over the deep chasm forming the

channel of the Ogwen, the embankment being carried forward from the rook

cutting, protected by high breastworks. From Capel-Curig to near the great

waterfall over the river Lugwy, about a mile of new road was cut; and a

still greater length from Bettws across the river Conway and along the face

of Dinas Hill to Rhyddlanfair, a distance of 3 miles; its steepest descent

being 1 in 22, diminishing to 1 in 45. By this improvement, the most

difficult and dangerous pass along the route through North Wales was

rendered safe and commodious.

Road Descent near Betws-y-Coed.

Another point of almost equal

difficulty occurred near Ty-Nant, through the rocky pass of Glynn Duffrws,

where the road was confined between steep rocks and rugged precipices: there

the way was widened and flattened by blasting, and thus reduced to the

general level; and so on eastward to Llangollen and Chirk, where the main

Shrewsbury road to London was joined.*[6]

Road above Nant Frrancon, North Wales.

By means of these admirable

roads the traffic of North Wales continues to be mainly carried on to this

day. Although railways have superseded coach-roads in the more level

districts, the hilly nature of Wales precludes their formation in that

quarter to any considerable extent; and even in the event of railways being

constructed, a large part of the traffic of every country must necessarily

continue to pass over the old high roads. Without them even railways would

be of comparatively little value; for a railway station is of use chiefly

because of its easy accessibility, and thus, both for passengers and

merchandise, the common roads of the country are as useful as ever they

were, though the main post-roads have in a great measure ceased to be

employed for the purposes for which they were originally designed.

The excellence of the roads

constructed by Mr. Telford through the formerly inaccessible counties of

North Wales was the theme of general praise; and their superiority, compared

with those of the richer and more level districts in the midland and western

English counties, becoming the subject of public comment, he was called upon

to execute like improvements upon that part of the post-road which extended

between Shrewsbury and the metropolis. A careful survey was made of the

several routes from London northward by Shrewsbury as far as Liverpool; and

the short line by Coventry, being 153 miles from London to Shrewsbury, was

selected as the one to be improved to the utmost.

Down to 1819, the road

between London and Coventry was in a very bad state, being so laid as to

become a heavy slough in wet weather. There were many steep hills which

required to be cut down, in some parts of deep clay, in others of deep sand.

A mail-coach had been tried to Banbury; but the road below Aylesbury was so

bad, that the Post-office authorities were obliged to give it up. The twelve

miles from Towcester to Daventry were still worse. The line of way was

covered with banks of dirt; in winter it was a puddle of from four to six

inches deep--quite as bad as it had been in Arthur Young's time; and when

horses passed along the road, they came out of it a mass of mud and

mire.*[7] There were also several steep and dangerous hills to be crossed;

and the loss of horses by fatigue in travelling by that route at the time

was very great.

Even the roads in the

immediate neighbourhood of the metropolis were little better, those under

the Highgate and Hampstead trust being pronounced in a wretched state. They

were badly formed, on a clay bottom, and being undrained, were almost always

wet and sloppy. The gravel was usually tumbled on and spread unbroken, so

that the materials, instead of becoming consolidated, were only rolled about

by the wheels of the carriages passing over them.

Mr. Telford applied the same

methods in the reconstruction of these roads that he had already adopted in

Scotland and Wales, and the same improvement was shortly felt in the more

easy passage over them of vehicles of all sorts, and in the great

acceleration of the mail service. At the same time, the line along the coast

from Bangor, by Conway, Abergele, St. Asaph, and Holywell, to Chester, was

greatly improved. As forming the mail road from Dublin to Liverpool, it was

considered of importance to render it as safe and level as possible. The

principal new cuts on this line were those along the rugged skirts of the

huge Penmaen-Mawr; around the base of Penmaen-Bach to the town of Conway;

and between St. Asaph and Holywell, to ease the ascent of Rhyall Hill.

But more important than all,

as a means of completing the main line of communication between England and

Ireland, there were the great bridges over the Conway and the Menai Straits

to be constructed. The dangerous ferries at those places had still to be

crossed in open boats, sometimes in the night, when the luggage and mails

were exposed to great risks. Sometimes, indeed, they were wholly lost and

passengers were lost with them. It was therefore determined, after long

consideration, to erect bridges over these formidable straits, and Mr.

Telford was employed to execute the works,--in what manner, we propose to

describe in the next chapter.

Footnotes for Chapter XI.

*[1] 'Life of Robert Owen,'

by himself.

*[2] 'Report from the Select

Committee on the Carlisle and Glasgow Road,' 28th June, 1815.

*[3 A diary is preserved of a

journey to Dublin from Grosvenor Square London, 12th June, 1787, in a coach

and four, accompanied by a post-chaise and pair, and five outriders. The

party reached Holyhead in four days, at a cost of 75L. 11s. 3d. The state of

intercourse between this country and the sister island at this part of the

account is strikingly set forth in the following entries:-- "Ferry at

Bangor, 1L. 10s.; expenses of the yacht hired to carry the party across the

channel, 28L. 7s. 9d.; duty on the coach, 7L. 13s. 4d.; boats on shore, 1L.

1s.; total, 114L. 3s. 4d." --Roberts's 'Social History of the Southern

Counties,' p. 504.

*[4] 'Second Report from

Committee on Holyhead Roads and Harbours,' 1810. (Parliamentary paper.)

*[5] "Many parts of the road

are extremely dangerous for a coach to travel upon. At several places

between Bangor and Capel-Curig there are a number of dangerous precipices

without fences, exclusive of various hills that want taking down. At Ogwen

Pool there is a very dangerous place where the water runs over the road,

extremely difficult to pass at flooded times. Then there is Dinas Hill, that

needs a side fence against a deep precipice. The width of the road is not

above twelve feet in the steepest part of the hill, and two carriages cannot

pass without the greatest danger. Between this hill and Rhyddlanfair there

are a number of dangerous precipices, steep hills, and difficult narrow

turnings. From Corwen to Llangollen the road is very narrow, long, and

steep; has no side fence, except about a foot and a half of mould or dirt,

which is thrown up to prevent carriages falling down three or four hundred

feet into the river Dee. Stage-coaches have been frequently overturned and

broken down from the badness of the road, and the mails have been

overturned; but I wonder that more and worse accidents have not happened,

the roads are so bad."--Evidence of Mr. William Akers, of the Post-office,

before Committee of the House of Commons, 1st June, 1815.

*[6] The Select Committee of

the House of Commons, in reporting as to the manner in which these works

were carried out, stated as follows:-- "The professional execution of the

new works upon this road greatly surpasses anything of the same kind in

these countries. The science which has been displayed in giving the general

line of the road a proper inclination through a country whose whole surface

consists of a succession of rocks, bogs, ravines, rivers, and precipices,

reflects the greatest credit upon the engineer who has planned them; but

perhaps a still greater degree of professional skill has been shown in the

construction, or rather the building, of the road itself. The great

attention which Mr. Telford has devoted, to give to the surface of the road

one uniform and moderately convex shape, free from the smallest inequality

throughout its whole breadth; the numerous land drains, and, when necessary,

shores and tunnels of substantial masonry, with which all the water arising

from springs or falling in rain is instantly carried off; the great care

with which a sufficient foundation is established for the road, and the

quality, solidity, and disposition of the materials that are put upon it,

are matters quite new in the system of road-making in these countries."--

'Report from the Select Committee on the Road from London to Holyhead in the

year 1819.'

*[7] Evidence of William

Waterhouse before the Select Committee, 10th March, 1819. |