|

No sooner were the Highland

roads and bridges in full progress, than attention was directed to the

improvement of the harbours round the coast. Very little had as yet been

done for them beyond what nature had effected. Happily, there was a public

fund at disposal--the accumulation of rents and profits derived from the

estates forfeited at the rebellion of 1745--which was available for the

purpose. The suppression of the rebellion did good in many ways. It broke

the feudal spirit, which lingered in the Highlands long after it had ceased

in every other part of Britain; it led to the effectual opening up of the

country by a system of good roads; and now the accumulated rents of the

defeated Jacobite chiefs were about to be applied to the improvement of the

Highland harbours for the benefit of the general population.

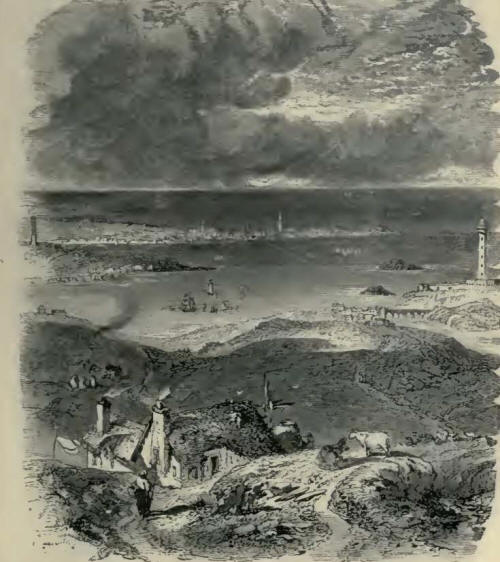

The harbour of Wick was one

of the first to which Mr. Telford's attention was directed. Mr. Rennie had

reported on the subject of its improvement as early as the year 1793, but

his plans were not adopted because their execution was beyond the means of

the locality at that time. The place had now, however, become of

considerable importance. It was largely frequented by Dutch fishermen during

the herring season; and it was hoped that, if they could be induced to form

a settlement at the place, their example might exercise a beneficial

influence upon the population.

Mr. Telford reported that, by

the expenditure of about 5890L., a capacious and well-protected tidal basin

might be formed, capable of containing about two hundred herring-busses. The

Commission adopted his plan, and voted the requisite funds for carrying out

the works, which were begun in 1808. The new station was named Pulteney

Town, in compliment to Sir William Pulteney, the Governor of the Fishery

Society; and the harbour was built at a cost of about 12,000L., of which

8500L. was granted from the Forfeited Estates Fund. A handsome stone bridge,

erected over the River Wick in 1805, after the design of our engineer,

connect's these improvements with the older town: it is formed of three

arches, having a clear waterway of 156 feet.

The money was well expended,

as the result proved; and Wick is now, we believe, the greatest fishing

station in the world. The place has increased from a little poverty-stricken

village to a large and thriving town, which swarms during the fishing season

with lowland Scotchmen, fair Northmen, broad-built Dutchmen, and kilted

Highlanders. The bay is at that time frequented by upwards of a thousand

fishing-boats and the take of herrings in some years amounts to more than a

hundred thousand barrels. The harbour has of late years been considerably

improved to meet the growing requirements of the herring trade, the

principal additions having been carried out, in 1823, by Mr. Bremner,*[1] a

native engineer of great ability.

Folkestone Harbour.

Improvements of a similar

kind were carried out by the Fishery Board at other parts of the coast, and

many snug and convenient harbours were provided at the principal fishing

stations in the Highlands and Western Islands. Where the local proprietors

were themselves found expending money in carrying out piers and harbours,

the Board assisted them with grants to enable the works to be constructed in

the most substantial manner and after the most approved plans. Thus, along

that part of the bold northern coast of the mainland of Scotland which

projects into the German Ocean, many old harbours were improved or new ones

constructed--as at Peterhead, Frazerburgh, Banff, Cullen, Burgh Head, and

Nairn. At Fortrose, in the Murray Frith; at Dingwall, in the Cromarty Frith;

at Portmaholmac, within Tarbet Ness, the remarkable headland of the Frith of

Dornoch; at Kirkwall, the principal town and place of resort in the Orkney

Islands, so well known from Sir Walter Scott's description of it in the

'Pirate;' at Tobermory, in the island of Mull; and at other points of the

coast, piers were erected and other improvements carried out to suit the

convenience of the growing traffic and trade of the country.

The principal works were

those connected with the harbours situated upon the line of coast extending

from the harbour of Peterhead, in the county of Aberdeen, round to the head

of the Murray Frith. The shores there are exposed to the full force of the

seas rolling in from the Northern Ocean; and safe harbours were especially

needed for the protection of the shipping passing from north to south.

Wrecks had become increasingly frequent, and harbours of refuge were loudly

called for. At one part of the coast, as many as thirty wrecks had occurred

within a very short time, chiefly for want of shelter.

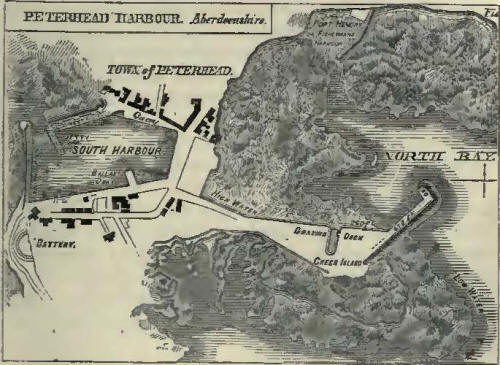

The situation of Peterhead

peculiarly well adapted it for a haven of refuge, and the improvement of the

port was early regarded as a matter of national importance. Not far from it,

on the south, are the famous Bullars or Boilers of Buchan--bold rugged

rocks, some 200 feet high, against which the sea beats with great fury,

boiling and churning in the deep caves and recesses with which they are

perforated. Peterhead stands on the most easterly part of the mainland of

Scotland, occupying the north-east side of the bay, and being connected with

the country on the northwest by an isthmus only 800 yards broad. In

Cromwell's time, the port possessed only twenty tons of boat tonnage, and

its only harbour was a small basin dug out of the rock. Even down to the

close of the sixteenth century the place was but an insignificant fishing

village. It is now a town bustling with trade, having long been the

principal seat of the whale fishery, 1500 men of the port being engaged in

that pursuit alone; and it sends out ships of its own building to all parts

of the world, its handsome and commodious harbours being accessible at all

winds to vessels of almost the largest burden.

Peterhead

It may be mentioned that

about sixty years since, the port was formed by the island called Keith

Island, situated a small distance eastward from the shore, between which and

the mainland an arm of the sea formerly passed. A causeway had, however,

been formed across this channel, thus dividing it into two small bays; after

which the southern one had been converted in to a harbour by means of two

rude piers erected along either side of it. The north inlet remained without

any pier, and being very inconvenient and exposed to the north-easterly

winds, it was little used.

Peterhead Harbour.

The first works carried out

at Peterhead were of a comparatively limited character, the old piers of the

south harbour having been built by Smeaton; but improvements proceeded apace

with the enterprise and wealth of the inhabitants. Mr. Rennie, and after him

Mr. Telford, fully reported as to the capabilities of the port and the best

means of improving it. Mr. Rennie recommended the deepening of the south

harbour and the extension of the jetty of the west pier, at the same time

cutting off all projections of rock from Keith Island on the eastward, so as

to render the access more easy. The harbour, when thus finished, would, he

estimated, give about 17 feet depth at high water of spring tides. He also

proposed to open a communication across the causeway between the north and

south harbours, and form a wet dock between them, 580 feet long and 225 feet

wide, the water being kept in by gates at each end. He further proposed to

provide an entirely new harbour, by constructing two extensive piers for the

effectual protection of the northern part of the channel, running out one

from a rock north of the Green Island, about 680 feet long, and another from

the Roan Head, 450 feet long, leaving an opening between them of 70 yards.

This comprehensive plan unhappily could not be carried out at the time for

want of funds; but it may be said to have formed the groundwork of all that

has been subsequently done for the improvement of the port of Peterhead.

It was resolved, in the first

place, to commence operations by improving the south harbour, and protecting

it more effectually from south-easterly winds. The bottom of the harbour was

accordingly deepened by cutting out 30,000 cubic yards of rocky ground; and

part of Mr. Rennie's design was carried out by extending the jetty of the

west pier, though only for a distance of twenty yards. These works were

executed under Mr. Telford's directions; they were completed by the end of

the year 1811, and proved to be of great public convenience.

The trade of the town,

however, so much increased, and the port was found of such importance as a

place of refuge for vessels frequenting the north seas, that in 1816 it was

determined to proceed with the formation of a harbour on the northern part

of the old channel; and the inhabitants having agreed among themselves to

contribute to the extent of 10,000L. towards carrying out the necessary

works, they applied for the grant of a like sum from the Forfeited Estates

Fund, which was eventually voted for the purpose. The plan adopted was on a

more limited scale than that Proposed by Mr. Rennie; but in the same

direction and contrived with the same object,--so that, when completed,

vessels of the largest burden employed in the Greenland fishery might be

able to enter one or other of the two harbours and find safe shelter, from

whatever quarter the wind might blow.

The works were vigorously

proceeded with, and had made considerable progress, when, in October, 1819,

a violent hurricane from the north-east, which raged along the coast for

several days, and inflicted heavy damage on many of the northern harbours,

destroyed a large part of the unfinished masonry and hurled the heaviest

blocks into the sea, tossing them about as if they had been pebbles. The

finished work had, however, stood well, and the foundations of the piers

under low water were ascertained to have remained comparatively uninjured.

There was no help for it but to repair the damaged work, though it involved

a heavy additional cost, one-half of which was borne by the Forfeited

Estates Fund and the remainder by the inhabitants. Increased strength was

also given to the more exposed parts of the pierwork, and the slope at the

sea side of the breakwater was considerably extended.*[2] Those alterations

in the design were carried out, together with a spacious graving-dock, as

shown in the preceding plan, and they proved completely successful, enabling

Peterhead to offer an amount of accommodation for shipping of a more

effectual kind than was at that time to be met with along the whole eastern

coast of Scotland.

The old harbour of

Frazerburgh, situated on a projecting point of the coast at the foot of

Mount Kennaird, about twenty miles north of Peterhead, had become so ruinous

that vessels lying within it received almost as little shelter as if they

had been exposed in the open sea. Mr. Rennie had prepared a plan for its

improvement by running out a substantial north-eastern pier; and this was

eventually carried out by Mr. Telford in a modified form, proving of

substantial service to the trade of the port. Since then a large and

commodious new harbour has been formed at the place, partly at the public

expense and partly at that of the inhabitants, rendering Frazerburgh a safe

retreat for vessels of war as well as merchantmen.

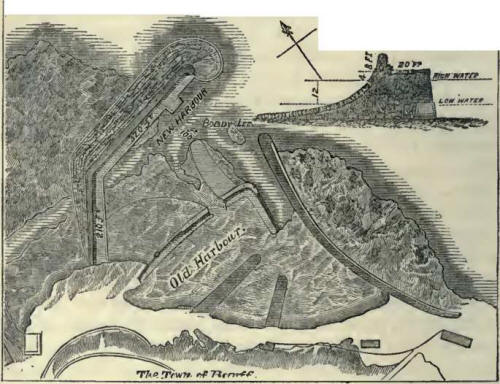

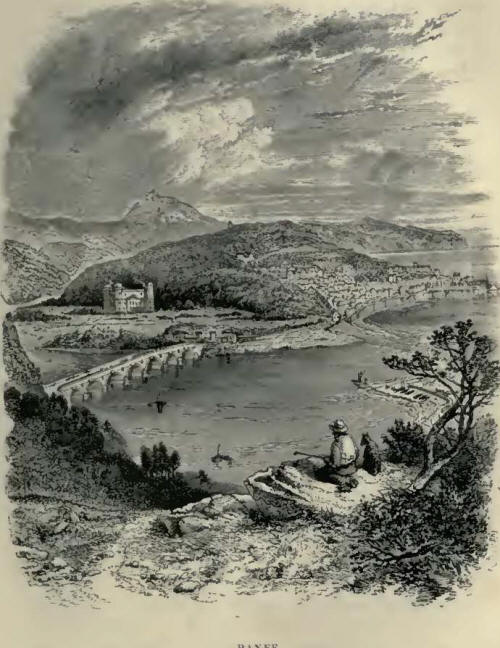

Banff.

Among the other important

harbour works on the northeast coast carried out by Mr. Telford under the

Commissioners appointed to administer the funds of the Forfeited Estates,

were those at Banff, the execution of which extended over many years; but,

though costly, they did not prove of anything like the same convenience as

those executed at Peterhead. The old harbour at the end of the ridge running

north and south, on which what is called the "sea town" of Banff is

situated, was completed in 1775, when the place was already considered of

some importance as a fishing station.

Banff Harbour.

This harbour occupies the

triangular space at the north-eastern extremity of the projecting point of

land, at the opposite side of which, fronting the north-west, is the little

town and harbour of Macduff. In 1816, Mr. Telford furnished the plan of a

new pier and breakwater, covering the old entrance, which presented an

opening to the N.N.E., with a basin occupying the intermediate space. The

inhabitants agreed to defray one half of the necessary cost, and the

Commissioners the other; and the plans having been approved, the works were

commenced in 1818. They were in full progress when, unhappily, the same

hurricane which in 1819 did so much injury to the works at Peterhead, also

fell upon those at Banff, and carried away a large part of the unfinished

pier. This accident had the effect of interrupting the work, as well as

increasing its cost; but the whole was successfully completed by the year

1822. Although the new harbour did not prove very safe, and exhibited a

tendency to become silted up with sand, it proved of use in many respects,

more particularly in preventing all swell and agitation in the old harbour,

which was thereby rendered the safest artificial haven in the Murray Firth.

It is unnecessary to specify

the alterations and improvements of a similar character, adapted to the

respective localities, which were carried out by our engineer at Burgh Head,

Nairn, Kirkwall, Tarbet, Tobermory, Portmaholmac, Dingwall (with its canal

two thousand yards long, connecting the town in a complete manner with the

Frith of Cromarty), Cullen, Fortrose, Ballintraed, Portree, Jura, Gourdon,

Invergordon, and other places. Down to the year 1823, the Commissioners had

expended 108,530L. on the improvements of these several ports, in aid of the

local contributions of the inhabitants and adjoining proprietors to a

considerably greater extent; the result of which was a great increase in the

shipping accommodation of the coast towns, to the benefit of the local

population, and of ship-owners and navigators generally.

Mr. Telford's principal

harbour works in Scotland, however, were those of Aberdeen and Dundee,

which, next to Leith (the port of Edinburgh), formed the principal havens

along the east coast. The neighbourhood of Aberdeen was originally so wild

and barren that Telford expressed his surprise that any class of men should

ever have settled there. An immense shoulder of the Grampian mountains

extends down to the sea-coast, where it terminates in a bold, rude

promontory. The country on either side of the Dee, which flows past the

town, was originally covered with innumerable granite blocks; one, called

Craig Metellan, lying right in the river's mouth, and forming, with the

sand, an almost effectual bar to its navigation. Although, in ancient times,

a little cultivable land lay immediately outside the town, the region beyond

was as sterile as it is possible for land to be in such a latitude. "Any

wher," says an ancient writer, "after yow pass a myll without the tonne, the

countrey is barren lyke, the hills craigy, the plaines full of marishes and

mosses, the feilds are covered with heather or peeble stons, the come feilds

mixt with thes bot few. The air is temperat and healthful about it, and it

may be that the citizens owe the acuteness of their wits thereunto and their

civill inclinations; the lyke not easie to be found under northerlie climats,

damped for the most pairt with air of a grosse consistence."*[3] But the old

inhabitants of Aberdeen and its neighbourhood were really as rough as their

soil. Judged by their records, they must have been dreadfully haunted by

witches and sorcerers down to a comparatively recent period; witch-burning

having been common in the town until the end of the sixteenth century. We

find that, in one year, no fewer than twenty-three women and one man were

burnt; the Dean of Guild Records containing the detailed accounts of the

"loads of peattis, tar barrellis," and other combustibles used in burning

them. The lairds of the Garioch, a district in the immediate neighbourhood,

seem to have been still more terrible than the witches, being accustomed to

enter the place and make an onslaught upon the citizens, according as local

rage and thirst for spoil might incline them. On one of such occasions,

eighty of the inhabitants were killed and wounded.*[4] Down even to the

middle of last century the Aberdonian notions of personal liberty seem to

have been very restricted; for between 1740 and 1746 we find that persons of

both sexes were kidnapped, put on board ships, and despatched to the

American plantations, where they were sold for slaves. Strangest of all, the

men who carried on this slave trade were local dignitaries, one of them

being a town's baillie, another the town-clerk depute. Those kidnapped were

openly "driven in flocks through the town, like herds of sheep, under the

care of a keeper armed with a whip."*[5] So open was the traffic that the

public workhouse was used for their reception until the ships sailed, and

when that was filled, the tolbooth or common prison was made use of. The

vessels which sailed from the harbour for America in 1743 contained no fewer

than sixty-nine persons; and it is supposed that, in the six years during

which the Aberdeen slave trade was at its height, about six hundred were

transported for sale, very few of whom ever returned.*[6] This slave traffic

was doubtless stimulated by the foreign ships beginning to frequent the

port; for the inhabitants were industrious, and their plaiding, linen, and

worsted stockings were in much request as articles of merchandise. Cured

salmon were also exported in large quantities. As early as 1659, a quay was

formed along the Dee towards the village of Foot Dee. "Beyond Futty," says

an old writer, "lyes the fisher-boat heavne; and after that, towards the

promontorie called Sandenesse, ther is to be seen a grosse bulk of a

building, vaulted and flatted above (the Blockhous they call it), begun to

be builded anno 1513, for guarding the entree of the harboree from pirats

and algarads; and cannon wer planted ther for that purpose, or, at least,

that from thence the motions of pirats might be tymouslie foreseen. This

rough piece of work was finished anno 1542, in which yer lykewayes the mouth

of the river Dee was locked with cheans of iron and masts of ships crossing

the river, not to be opened bot at the citizens' pleasure."*[7] After the

Union, but more especially after the rebellion of 1745, the trade of

Aberdeen made considerable progress. Although Burns, in 1787, briefly

described the place as a "lazy toun," the inhabitants were displaying much

energy in carrying out improvements in their port.*[8] In 1775 the

foundation-stone of the new pier designed by Mr. Smeaton was laid with great

ceremony, and, the works proceeding to completion, a new pier, twelve

hundred feet long, terminating in a round head, was finished in less than

six years. The trade of the place was, however, as yet too small to justify

anything beyond a tidal harbour, and the engineer's views were limited to

that object. He found the river meandering over an irregular space about

five hundred yards in breadth; and he applied the only practicable remedy,

by confining the channel as much as the limited means placed at his disposal

enabled him to do, and directing the land floods so as to act upon and

diminish the bar. Opposite the north pier, on the south side of the river,

Smeaton constructed a breast-wall about half the length of the Pier. Owing,

however, to a departure from that engineer's plans, by which the pier was

placed too far to the north, it was found that a heavy swell entered the

harbour, and, to obviate this formidable inconvenience, a bulwark was

projected from it, so as to occupy about one third of the channel entrance.

The trade of the place

continuing to increase, Mr. Rennie was called upon, in 1797, to examine and

report upon the best means of improving the harbour, when he recommended the

construction of floating docks upon the sandy flats called Foot Dee. Nothing

was done at the time, as the scheme was very costly and considered beyond

the available means of the locality. But the magistrates kept the subject in

mind; and when Mr. Telford made his report on the best means of improving

the harbour in 1801, he intimated that the inhabitants were ready to

cooperate with the Government in rendering it capable of accommodating ships

of war, as far as their circumstances would permit.

In 1807, the south pier-head,

built by Smeaton, was destroyed by a storm, and the time had arrived when

something must be done, not only to improve but even to preserve the port.

The magistrates accordingly proceeded, in 1809, to rebuild the pier-head of

cut granite, and at the same time they applied to Parliament for authority

to carry out further improvements after the plan recommended by Mr. Telford;

and the necessary powers were conferred in the following year. The new works

comprehended a large extension of the wharfage accommodation, the

construction of floating and graving docks, increased means of scouring the

harbour and ensuring greater depth of water on the bar across the river's

mouth, and the provision of a navigable communication between the

Aberdeenshire Canal and the new harbour.

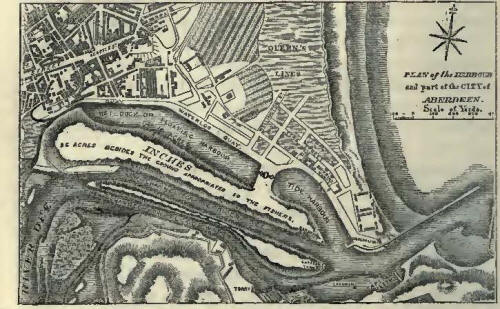

Plan of Aberdeen Harbour

The extension of the north

pier was first proceeded with, under the superintendence of John Gibb, the

resident engineer; and by the year 1811 the whole length of 300 additional

feet had been completed. The beneficial effects of this extension were so

apparent, that a general wish was expressed that it should be carried

further; and it was eventually determined to extend the pier 780 feet beyond

Smeaton's head, by which not only was much deeper water secured, but vessels

were better enabled to clear the Girdleness Point. This extension was

successfully carried out by the end of the year 1812. A strong breakwater,

about 800 feet long, was also run out from the south shore, leaving a space

of about 250 feet as an entrance, thereby giving greater protection to the

shipping in the harbour, while the contraction of the channel, by increasing

the "scour," tended to give a much greater depth of water on the bar.

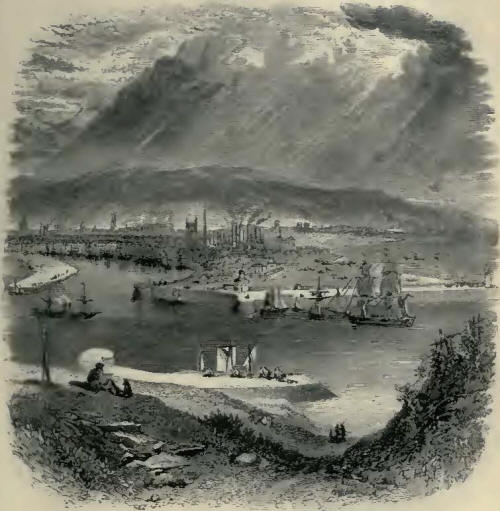

Aberdeen Harbour.

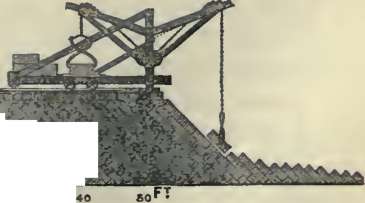

The outer head of the pier

was seriously injured by the heavy storms of the two succeeding winters,

which rendered it necessary to alter its formation to a very flat slope of

about five to one all round the head.*[9]

Section of pier-head work.

New wharves were at the same

time constructed inside the harbour; a new channel for the river was

excavated, which further enlarged the floating space and wharf

accommodation; wet and dry docks were added; until at length the quay

berthage amounted to not less than 6290 feet, or nearly a mile and a quarter

in length. By these combined improvements an additional extent of quay room

was obtained of about 4000 feet; an excellent tidal harbour was formed, in

which, at spring tides, the depth of water is about 15 feet; while on the

bar it was increased to about 19 feet. The prosperity of Aberdeen had

meanwhile been advancing apace. The city had been greatly beautified and

enlarged: shipbuilding had made rapid progress; Aberdeen clippers became

famous, and Aberdeen merchants carried on a trade with all parts of the

world; manufactures of wool, cotton, flax, and iron were carried on with

great success; its population rapidly increased; and, as a maritime city,

Aberdeen took rank as the third in Scotland, the tonnage entering the port

having increased from 50,000 tons in 1800 to about 300,000 in 1860.

Improvements of an equally

important character were carried out by Mr. Telford in the port of Dundee,

also situated on the east coast of Scotland, at the entrance to the Frith of

Tay. There are those still living at the place who remember its former

haven, consisting of a crooked wall, affording shelter to only a few

fishing-boats or smuggling vessels--its trade being then altogether paltry,

scarcely deserving the name, and its population not one fifth of what it now

is. Helped by its commodious and capacious harbour, it has become one of the

most populous and thriving towns on the east coast.

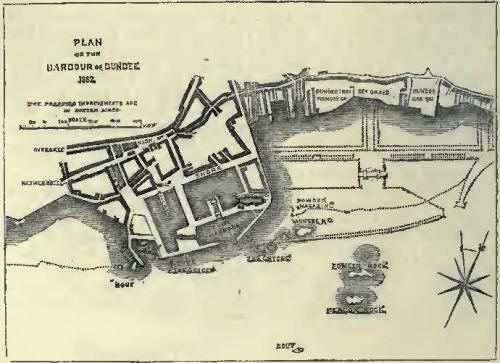

Plan of Dundee Harbour.

The trade of the place took a

great start forward at the close of the war, and Mr. Telford was called upon

to supply the plans of a new harbour. His first design, which he submitted

in 1814, was of a comparatively limited character; but it was greatly

enlarged during the progress of the works. Floating docks were added, as

well as graving docks for large vessels. The necessary powers were obtained

in 1815; the works proceeded vigorously under the Harbour Commissioners, who

superseded the old obstructive corporation; and in 1825 the splendid new

floating dock--750 feet long by 450 broad, having an entrance-lock 170 feet

long and 40 feet wide--was opened to the shipping of all countries.

Dundee Harbour.

Footnotes for Chapter IX.

*[1] Hugh Millar, in his 'Cruise of the Betsy,' attributes the invention of

columnar pier-work to Mr. Bremner, whom he terms "the Brindley of Scotland."

He has acquired great fame for his skill in raising sunken ships, having

warped the Great Britain steamer off the shores of Dundrum Bay. But we

believe Mr. Telford had adopted the practice of columnar pier-work before

Mr. Bremner, in forming the little harbour of Folkestone in 1808, where the

work is still to be seen quite perfect. The most solid mode of laying stone

on land is in flat courses; but in open pier work the reverse process is

adopted. The blocks are laid on end in columns, like upright beams jammed

together. Thus laid, the wave which dashes against them is broken, and

spends itself on the interstices; where as, if it struck the broad solid

blocks, the tendency would be to lift them from their beds and set the work

afloat; and in a furious storm such blocks would be driven about almost like

pebbles. The rebound from flat surfaces is also very heavy, and produces

violent commotion; where as these broken, upright, columnar-looking piers

seem to absorb the fury of the sea, and render its wildest waves

comparatively innocuous.

*[2] 'Memorials from

Peterhead and Banff, concerning Damage occasioned by a Storm.' Ordered by

the House of Commons to be printed, 5th July, 1820. [242.]

*[3] 'A Description of Bothe

Touns of Aberdeene.' By James Gordon, Parson of Rothiemay. Reprinted in

Gavin Turreff's 'Antiquarian Gleanings from Aberdeenshire Records.'

Aberdeen, 1889.

*[4] Robertson's 'Book of

Bon-Accord.'

*[5] Ibid., quoted in

Turreff's 'Antiquarian Gleanings,' p. 222.

*[6] One of them, however,

did return--Peter Williamson, a native of the town, sold for a slave in

Pennsylvania, "a rough, ragged, humle-headed, long, stowie, clever boy,"

who, reaching York, published an account of the infamous traffic, in a

pamphlet which excited extraordinary interest at the time, and met with a

rapid and extensive circulation. But his exposure of kidnapping gave very

great offence to the magistrates, who dragged him before their tribunal as

having "published a scurrilous and infamous libel on the corporation," and

he was sentenced to be imprisoned until he should sign a denial of the truth

of his statements. He brought an action against the corporation for their

proceedings, and obtained a verdict and damages; and he further proceeded

against Baillie Fordyce (one of his kidnappers, and others, from whom he

obtained 200L. damages, with costs. The system was thus effectually put a

stop to.

*[8] 'A Description of Bothe

Touns of Aberdeene.' By James Gordon, Parson of Rothiemay. Quoted by Turreff,

p. 109.

*[8] Communication with

London was as yet by no means frequent, and far from expeditious, as the

following advertisement of 1778 will show:--"For London: To sail positively

on Saturday next, the 7th November, wind and weather permitting, the

Aberdeen smack. Will lie a short time at London, and, if no convoy is

appointed, will sail under care of a fleet of colliers the best convoy of

any. For particulars apply," &c., &c.

*[9] "The bottom under the

foundations," says Mr. Gibb, in his description of the work, "is nothing

better than loose sand and gravel, constantly thrown up by the sea on that

stormy coast, so that it was necessary to consolidate the work under low

water by dropping large stones from lighters, and filling the interstices

with smaller ones, until it was brought within about a foot of the level of

low water, when the ashlar work was commenced; but in place of laying the

stones horizontally in their beds, each course was laid at an angle of 45

degrees, to within about 18 inches of the top, when a level coping was

added. This mode of building enabled the work to be carried on

expeditiously, and rendered it while in progress less liable to temporary

damage, likewise affording three points of bearing; for while the ashlar

walling was carrying up on both sides, the middle or body of the pier was

carried up at the same time by a careful backing throughout of large

rubble-stone, to within 18 inches of the top, when the whole was covered

with granite coping and paving 18 inches deep, with a cut granite parapet

wall on the north side of the whole length of the pier, thus protected for

the convenience of those who might have occasion to frequent it."--Mr.

Gibb's 'Narrative of Aberdeen Harbour Works.' |