|

In an early chapter of this

volume we have given a rapid survey of the state of Scotland about the

middle of last century. We found a country without roads, fields lying

uncultivated, mines unexplored, and all branches of industry languishing, in

the midst of an idle, miserable, and haggard population. Fifty years passed,

and the state of the Lowlands had become completely changed. Roads had been

made, canals dug, coal-mines opened up, ironworks established; manufactures

were extending in all directions; and Scotch agriculture, instead of being

the worst, was admitted to be the best in the island.

"I have been perfectly

astonished," wrote Romilly from Stirling, in 1793, "at the richness and high

cultivation of all the tract of this calumniated country through which I

have passed, and which extends quite from Edinburgh to the mountains where I

now am. It is true, however; that almost everything which one sees to admire

in the way of cultivation is due to modem improvements; and now and then one

observes a few acres of brown moss, contrasting admirably with the corn-fieids

to which they are contiguous, and affording a specimen of the dreariness and

desolation which, only half a century ago, overspread a country now highly

cultivated, and become a most copious source of human happiness."*[1] It

must, however, be admitted that the industrial progress thus described was

confined almost entirely to the Lowlands, and had scarcely penetrated the

mountainous regions lying towards the north-west. The rugged nature of that

part of the country interposed a formidable barrier to improvement, and the

district still remained very imperfectly opened up. The only practicable

roads were those which had been made by the soldiery after the rebellions of

1715 and '45, through counties which before had been inaccessible except by

dangerous footpaths across high and rugged mountains. An old epigram in

vogue at the end of last century ran thus:

"Had you seen these roads

before they were made,

You'd lift up your hands and bless General Wade!"

Being constructed by soldiers

for military purposes, they were first known as "military roads." One was

formed along the Great Glen of Scotland, in the line of the present

Caledonian Canal, connected with the Lowlands by the road through Glencoe by

Tyndrum down the western banks of Loch Lomond; another, more northerly,

connected Fort Augustus with Dunkeld by Blair Athol; while a third, still

further to the north and east, connected Fort George with Cupar-in-Angus by

Badenoch and Braemar.

The military roads were about

eight hundred miles in extent, and maintained at the public expense. But

they were laid out for purposes of military occupation rather than for the

convenience of the districts which they traversed. Hence they were

comparatively little used, and the Highlanders, in passing from one place to

another, for the most part continued to travel by the old cattle tracks

along the mountains. But the population were as yet so poor and so

spiritless, and industry was in so backward a state all over the Highlands,

that the want of more convenient communications was scarcely felt.

Though there was plenty of

good timber in certain districts, the bark was the only part that could be

sent to market, on the backs of ponies, while the timber itself was left to

rot upon the ground. Agriculture was in a surprisingly backward state. In

the remoter districts only a little oats or barley was grown, the chief part

of which was required for the sustenance of the cattle during winter. The

Rev. Mr. Macdougall, minister of the parishes of Lochgoilhead and Kilmorich,

in Argyleshire, described the people of that part of the country, about the

year 1760, as miserable beyond description. He says, "Indolence was almost

the only comfort they enjoyed. There was scarcely any variety of

wretchedness with which they were not obliged to struggle, or rather to

which they were not obliged to submit. They often felt what it was to want

food.... To such an extremity were they frequently reduced, that they were

obliged to bleed their cattle, in order to subsist some time on the blood

(boiled); and even the inhabitants of the glens and valleys repaired in

crowds to the shore, at the distance of three or four miles, to pick up the

scanty provision which the shell-fish afforded them."*[2]

The plough had not yet

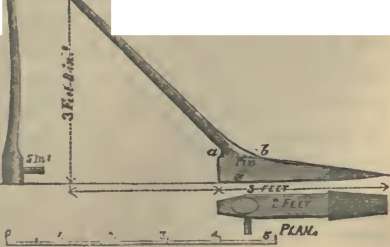

penetrated into the Highlands; an instrument called the cas-chrom*[3]

The Cas-Chrom.

--literally the "crooked

foot"--the use of which had been forgotten for hundreds of years in every

other country in Europe, was almost the only tool employed in tillage in

those parts of the Highlands which were separated by almost impassable

mountains from the rest of the United Kingdom.

The native population were by

necessity peaceful. Old feuds were restrained by the strong arm of the law,

if indeed the spirit of the clans had not been completely broken by the

severe repressive measures which followed the rebellion of Forty-five. But

the people had hot yet learnt to bend their backs, like the Sassenach, to

the stubborn soil, and they sat gloomily by their turf-fires at home, or

wandered away to settle in other lands beyond the seas. It even began to be

feared that the country would so on be entirely depopulated; and it became a

matter of national concern to devise methods of opening up the district so

as to develope its industry and afford improved means of sustenance for its

population. The poverty of the inhabitants rendered the attempt to construct

roads--even had they desired them--beyond their scanty means; but the

ministry of the day entertained the opinion that, by contributing a certain

proportion of the necessary expense, the proprietors of Highland estates

might be induced to advance the remainder; and on this principle the

construction of the new roads in those districts was undertaken.

The country lying to the west

of the Great Glen was absolutely without a road of any kind. The only

district through which travellers passed was that penetrated by the great

Highland road by Badenoch, between Perth and Inverness; and for a

considerable time after the suppression of the rebellion of 1745, it was

infested by gangs of desperate robbers. So unsafe was the route across the

Grampians, that persons who had occasion to travel it usually made their

wills before setting out. Garrons, or little Highland ponies, were then used

by the gentry as well as the peasantry. Inns were few and bad; and even when

postchaises were introduced at Inverness, the expense of hiring one was

thought of for weeks, perhaps months, and arrangements were usually made for

sharing it among as many individuals as it would contain. If the harness and

springs of the vehicle held together, travellers thought themselves

fortunate in reaching Edinburgh, jaded and weary, but safe in purse and

limb, on the eighth day after leaving Inverness.*[4] Very few persons then

travelled into the Highlands on foot, though Bewick, the father of

wood-engraving, made such a journey round Loch Lomond in 1775. He relates

that his appearance excited the greatest interest at the Highland huts in

which he lodged, the women curiously examining him from head to foot, having

never seen an Englishman before. The strange part of his story is, that he

set out upon his journey from Cherryburn, near Newcastle, with only three

guineas sewed in his waistband, and when he reached home he had still a few

shillings left in his pocket!

In 1802, Mr. Telford was

called upon by the Government to make a survey of Scotland, and report as to

the measures which were necessary for the improvement of the roads and

bridges of that part of the kingdom, and also on the means of promoting the

fisheries on the east and west coasts, with the object of better opening up

the country and preventing further extensive emigration. Previous to this

time he had been employed by the British Fisheries Society-- of which his

friend Sir William Pulteney was Governor--to inspect the harbours at their

several stations, and to devise a plan for the establishment of a fishery on

the coast of Caithness. He accordingly made an extensive tour of Scotland,

examining, among other harbours, that of Annan; from which he proceeded

northward by Aberdeen to Wick and Thurso, returning to Shrewsbury by

Edinburgh and Dumfries.*[5] He accumulated a large mass of data for his

report, which was sent in to the Fishery Society, with charts and plans, in

the course of the following year.

In July, 1802, he was

requested by the Lords of the Treasury, most probably in consequence of the

preceding report, to make a further survey of the interior of the Highlands,

the result of which he communicated in his report presented to Parliament in

the following year. Although full of important local business, "kept

running," as he says, "from town to country, and from country to town, never

when awake, and perhaps not always when asleep, have my Scotch surveys been

absent from my mind." He had worked very hard at his report, and hoped that

it might be productive of some good.

The report was duly

presented, printed,*[6] and approved; and it formed the starting-point of a

system of legislation with reference to the Highlands which extended over

many years, and had the effect of completely opening up that romantic but

rugged district of country, and extending to its inhabitants the advantages

of improved intercourse with the other parts of the kingdom. Mr. Telford

pointed out that the military roads were altogether inadequate to the

requirements of the population, and that the use of them was in many places

very much circumscribed by the want of bridges over some of the principal

rivers. For instance, the route from Edinburgh to Inverness, through the

Central Highlands, was seriously interrupted at Dunkeld, where the Tay is

broad and deep, and not always easy to be crossed by means of a boat. The

route to the same place by the east coast was in like manner broken at

Fochabers, where the rapid Spey could only be crossed by a dangerous ferry.

The difficulties encountered

by gentlemen of the Bar, in travelling the north circuit about this time,

are well described by Lord Cockburn in his 'Memorials.' "Those who are born

to modem travelling," he says, "can scarcely be made to understand how the

previous age got on. The state of the roads may be judged of from two or

three facts. There was no bridge over the Tay at Dunkeld, or over the Spey

at Fochabers, or over the Findhorn at Forres. Nothing but wretched pierless

ferries, let to poor cottars, who rowed, or hauled, or pushed a crazy boat

across, or more commonly got their wives to do it. There was no mail-coach

north of Aberdeen till, I think, after the battle of Waterloo. What it must

have been a few years before my time may be judged of from Bozzy's 'Letter

to Lord Braxfield,' published in 1780. He thinks that, besides a carriage

and his own carriage-horses, every judge ought to have his sumpter-horse,

and ought not to travel faster than the waggon which carried the baggage of

the circuit. I understood from Hope that, after 1784, when he came to the

Bar, he and Braxfield rode a whole north circuit; and that, from the

Findhorn being in a flood, they were obliged to go up its banks for about

twenty-eight miles to the bridge of Dulsie before they could cross. I myself

rode circuits when I was Advocate-Depute between 1807 and 1810. The fashion

of every Depute carrying his own shell on his back, in the form of his own

carriage, is a piece of very modern antiquity."*[7] North of Inverness,

matters were, if possible, still worse. There was no bridge over the Beauly

or the Conan. The drovers coming south swam the rivers with their cattle.

There being no roads, there was little use for carts. In the whole county of

Caithness, there was scarcely a farmer who owned a wheel-cart. Burdens were

conveyed usually on the backs of ponies, but quite as often on the backs of

women.*[8] The interior of the county of Sutherland being almost

inaccessible, the only track lay along the shore, among rocks and sand, and

was covered by the sea at every tide. "The people lay scattered in

inaccessible straths and spots among the mountains, where they lived in

family with their pigs and kyloes (cattle), in turf cabins of the most

miserable description; they spoke only Gaelic, and spent the whole of their

time in indolence and sloth. Thus they had gone on from father to son, with

little change, except what the introduction of illicit distillation had

wrought, and making little or no export from the country beyond the few lean

kyloes, which paid the rent and produced wherewithal to pay for the oatmeal

imported."*[9] Telford's first recommendation was, that a bridge should be

thrown across the Tay at Dunkeld, to connect the improved lines of road

proposed to be made on each side of the river. He regarded this measure as

of the first importance to the Central Highlands; and as the Duke of Athol

was willing to pay one-half of the cost of the erection, if the Government

would defray the other--the bridge to be free of toll after a certain

period--it appeared to the engineer that this was a reasonable and just mode

of providing for the contingency. In the next place, he recommended a bridge

over the Spey, which drained a great extent of mountainous country, and,

being liable to sudden inundations, was very dangerous to cross. Yet this

ferry formed the only link of communication between the whole of the

northern counties. The site pointed out for the proposed bridge was adjacent

to the town of Fochabers, and here also the Duke of Gordon and other county

gentlemen were willing to provide one-half of the means for its erection.

Mr. Telford further described

in detail the roads necessary to be constructed in the north and west

Highlands, with the object of opening up the western parts of the counties

of Inverness and Ross, and affording a ready communication from the Clyde to

the fishing lochs in the neighbourhood of the Isle of Skye. As to the means

of executing these improvements, he suggested that Government would be

justified in dealing with the Highland roads and bridges as exceptional and

extraordinary works, and extending the public aid towards carrying them into

effect, as, but for such assistance, the country must remain, perhaps for

ages to come, imperfectly opened up. His report further embraced certain

improvements in the harbours of Aberdeen and Wick, and a description of the

country through which the proposed line of the Caledonian Canal would

necessarily pass-- a canal which had long been the subject of inquiry, but

had not as yet emerged from a state of mere speculation.

The new roads, bridges, and

other improvements suggested by the engineer, excited much interest in the

north. The Highland Society voted him their thanks by acclamation; the

counties of Inverness and Ross followed; and he had letters of thanks and

congratulation from many of the Highland chiefs. "If they will persevere,"

says he,"with anything like their present zeal, they will have the

satisfaction of greatly improving a country that has been too long

neglected. Things are greatly changed now in the Highlands. Even were the

chiefs to quarrel, de'il a Highlandman would stir for them. The lairds have

transferred their affections from their people to flocks of sheep, and the

people have lost their veneration for the lairds. It seems to be the natural

progress of society; but it is not an altogether satisfactory change. There

were some fine features in the former patriarchal state of society; but now

clanship is gone, and chiefs and people are hastening into the opposite

extreme. This seems to me to be quite wrong."*[10] In the same year, Telford

was elected a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, on which occasion he

was proposed and supported by three professors; so that the former Edinburgh

mason was rising in the world and receiving due honour in his own country.

The effect of his report was such, that in the session of 1803 a

Parliamentary Commission was appointed, under whose direction a series of

practical improvements was commenced, which issued in the construction of

not less than 920 additional miles of roads and bridges throughout the

Highlands, one-half of the cost of which was defrayed by the Government and

the other half by local assessment. But in addition to these main lines of

communication, numberless county roads were formed by statute labour, under

local road Acts and by other means; the land-owners of Sutherland alone

constructing nearly 300 miles of district roads at their own cost.

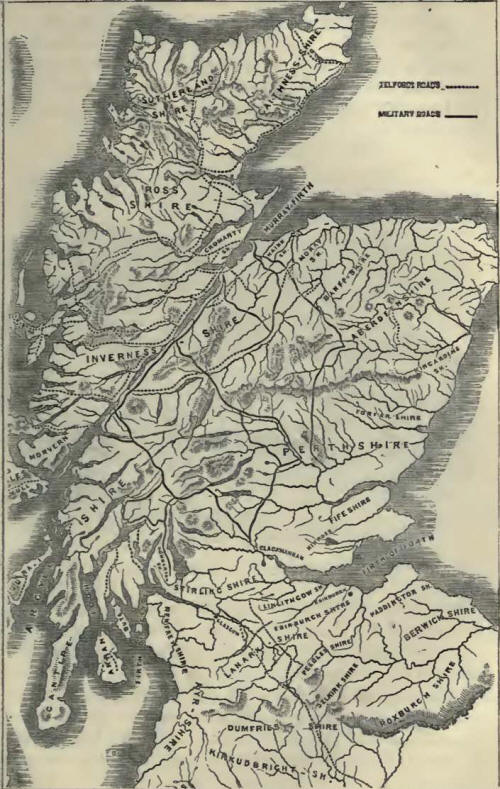

Map of Telford's Roads.

By the end of the session of

1803, Telford received his instructions from Mr. Vansittart as to the

working survey he was forthwith required to enter upon, with a view to

commencing practical operations; and he again proceeded to the Highlands to

lay out the roads and plan the bridges which were most urgently needed. The

district of the Solway was, at his representation, included, with the object

of improving the road from Carlisle to Portpatrick--the nearest point at

which Great Britain meets the Irish coast, and where the sea passage forms

only a sort of wide ferry.

It would occupy too much

space, and indeed it is altogether unnecessary, to describe in detail the

operations of the Commission and of their engineer in opening up the

communications of the Highlands. Suffice it to say, that one of the first

things taken in hand was the connection of the existing lines of road by

means of bridges at the more important points; such as at Dunkeld over the

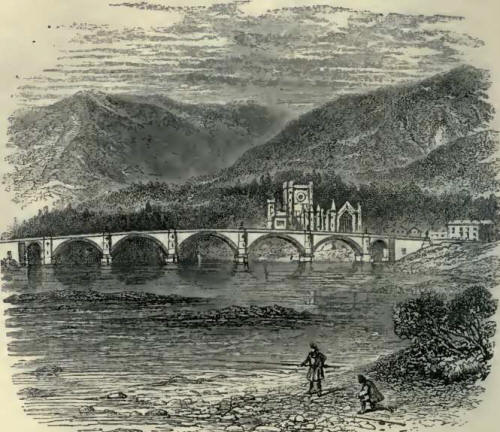

Tay, and near Dingwall over the Conan and Orrin. That of Dunkeld was the

most important, as being situated at the entrance to the Central Highlands;

and at the second meeting of the Commissioners Mr. Telford submitted his

plan and estimates of the proposed bridge. In consequence of some difference

with the Duke of Athol as to his share of the expense--which proved to be

greater than he had estimated--some delay occurred in beginning the work;

but at length it was fairly started, and, after being about three years in

hand, the structure was finished and opened for traffic in 1809.

Dunkeld Bridge.

The bridge is a handsome one

of five river and two land arches.The span of the centre arch is 90 feet, of

the two adjoining it 84 feet, and of the two side arches 74 feet; affording

a clear waterway of 446 feet. The total breadth of the roadway and foot

paths is 28 feet 6 inches. The cost of the structure was about 14,000L.,

one-half of which was defrayed by the Duke of Athol. Dunkeld bridge now

forms a fine feature in a landscape not often surpassed, and which presents

within a comparatively small compass a great variety of character and

beauty.

The communication by road

north of Inverness was also perfected by the construction of a bridge of

five arches over the Beauly, and another of the same number over the Conan,

the central arch being 65 feet span; and the formerly wretched bit of road

between these points having been put in good repair, the town of Dingwall

was thenceforward rendered easily approachable from the south. At the same

time, a beginning was made with the construction of new roads through the

districts most in need of them. The first contracted for, was the Loch-na-Gaul

road, from Fort William to Arasaig, on the western coast, nearly opposite

the island of Egg.

Another was begun from Loch

Oich, on the line of the Caledonian Canal, across the middle of the

Highlands, through Glengarry, to Loch Hourn on the western sea. Other roads

were opened north and south; through Morvern to Loch Moidart; through Glen

Morrison and Glen Sheil, and through the entire Isle of Skye; from Dingwall,

eastward, to Lochcarron and Loch Torridon, quite through the county of Ross;

and from Dingwall, northward, through the county of Sutherland as far as

Tongue on the Pentland Frith; while another line, striking off at the head

of the Dornoch Frith, proceeded along the coast in a north-easterly

direction to Wick and Thurso, in the immediate neighbourhood of John o'

Groats.

There were numerous other

subordinate lines of road which it is unnecessary to specify in detail; but

some idea may be formed of their extent, as well as of the rugged character

of the country through which they were carried, when we state that they

involved the construction of no fewer than twelve hundred bridges. Several

important bridges were also erected at other points to connect existing

roads, such as those at Ballater and Potarch over the Dee; at Alford over

the Don: and at Craig-Ellachie over the Spey.

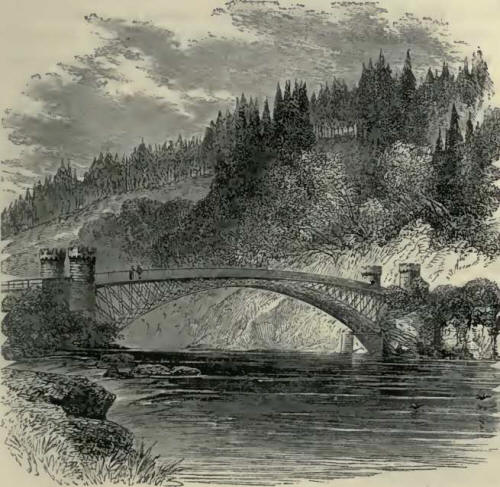

The last-named bridge is a

remarkably elegant structure, thrown over the Spey at a point where the

river, rushing obliquely against the lofty rock of Craig-Ellachie,*[11] has

formed for itself a deep channel not exceeding fifty yards in breadth. Only

a few years before, there had not been any provision for crossing this river

at its lower parts except the very dangerous ferry at Fochabers. The Duke of

Gordon had, however, erected a suspension bridge at that town, and the

inconvenience was in a great measure removed. Its utility was so generally

felt, that the demand arose for a second bridge across the river; for there

was not another by which it could be crossed for a distance of nearly fifty

miles up Strath Spey.

It was a difficult stream to

span by a bridge at any place, in consequence of the violence with which the

floods descended at particular seasons. Sometimes, even in summer, when not

a drop of rain had fallen, the flood would come down the Strath in great

fury, sweeping everything before it; this remarkable phenomenon being

accounted for by the prevalence of a strong south-westerly wind, which blew

the loch waters from their beds into the Strath, and thus suddenly filled

the valley of the Spey.*[12] The same phenomenon, similarly caused, is also

frequently observed in the neighbouring river, the Findhorn, cooped up in

its deep rocky bed, where the water sometimes comes down in a wave six feet

high, like a liquid wall, sweeping everything before it.

To meet such a contingency,

it was deemed necessary to provide abundant waterway, and to build a bridge

offering as little resistance as possible to the passage of the Highland

floods. Telford accordingly designed for the passage of the river at

Craig-Ellachie a light cast-iron arch of 150 feet span, with a rise of 20

feet, the arch being composed of four ribs, each consisting of two

concentric arcs forming panels, which are filled in with diagonal bars.

The roadway is 15 feet wide,

and is formed of another arc of greater radius, attached to which is the

iron railing; the spandrels being filled by diagonal ties, forming

trelliswork. Mr. Robert Stephenson took objection to the two dissimilar

arches, as liable to subject the structure, from variations of temperature,

to very unequal strains. Nevertheless this bridge, as well as many others

constructed by Mr. Telford after a similar plan, has stood perfectly well,

and to this day remains a very serviceable structure.

Craig-Ellachie Bridge.

Its appearance is highly

picturesque. The scattered pines and beech trees on the side of the

impending mountain, the meadows along the valley of the Spey, and the

western approach road to the bridge cut deeply into the face of the rock,

combine, with the slender appearance of the iron arch, in rendering this

spot one of the most remarkable in Scotland.*[13] An iron bridge of a

similar span to that at Craig-Ellachie had previously been constructed

across the head of the Dornoch Frith at Bonar, near the point where the

waters of the Shin join the sea. The very severe trial which this structure

sustained from the tremendous blow of an irregular mass of fir-tree logs,

consolidated by ice, as well as, shortly after, from the blow of a schooner

which drifted against it on the opposite side, and had her two masts knocked

off by the collision, gave him every confidence in the strength of this form

of construction, and he accordingly repeated it in several of his subsequent

bridges, though none of them are comparable in beauty with that of

Craig-Ellachie.

Thus, in the course of

eighteen years, 920 miles of capital roads, connected together by no fewer

than 1200 bridges, were added to the road communications of the Highlands,

at an expense defrayed partly by the localities immediately benefited, and

partly by the nation. The effects of these twenty years' operations were

such as follow the making of roads everywhere--development of industry and

increase of civilization. In no districts were the benefits derived from

them more marked than in the remote northern counties of Sutherland and

Caithness. The first stage-coaches that ran northward from Perth to

Inverness were tried in 1806, and became regularly established in 1811; and

by the year 1820 no fewer than forty arrived at the latter town in the

course of every week, and the same number departed from it. Others were

established in various directions through the highlands, which were rendered

as accessible as any English county.

Agriculture made rapid

progress. The use of carts became practicable, and manure was no longer

carried to the field on women's backs. Sloth and idleness gradually

disappeared before the energy, activity, and industry which were called into

life by the improved communications. Better built cottages took the place of

the old mud biggins with holes in their roofs to let out the smoke. The pigs

and cattle were treated to a separate table. The dunghill was turned to the

outside of the house. Tartan tatters gave place to the produce of Manchester

and Glasgow looms; and very soon few young persons were to be found who

could not both read and write English.

But not less remarkable were

the effects of the road-making upon the industrial habits of the people.

Before Telford went into the Highlands, they did not know how to work,

having never been accustomed to labour continuously and systematically. Let

our engineer himself describe the moral influences of his Highland

contracts:--"In these works," says he, "and in the Caledonian Canal, about

three thousand two hundred men have been annually employed. At first, they

could scarcely work at all: they were totally unacquainted with labour; they

could not use the tools. They have since become excellent labourers, and of

the above number we consider about one-fourth left us annually, taught to

work. These undertakings may, indeed, be regarded in the light of a working

academy; from which eight hundred men have annually gone forth improved

workmen. They have either returned to their native districts with the

advantage of having used the most perfect sort of tools and utensils (which

alone cannot be estimated at less than ten per cent. on any sort of labour),

or they have been usefully distributed through the other parts of the

country. Since these roads were made accessible, wheelwrights and

cartwrights have been established, the plough has been introduced, and

improved tools and utensils are generally used. The plough was not

previously employed; in the interior and mountainous parts they used crooked

sticks, with iron on them, drawn or pushed along. The moral habits of the

great masses of the working classes are changed; they see that they may

depend on their own exertions for support: this goes on silently, and is

scarcely perceived until apparent by the results. I consider these

improvements among the greatest blessings ever conferred on any country.

About two hundred thousand pounds has been granted in fifteen years. It has

been the means of advancing the country at least a century."

The progress made in the

Lowland districts of Scotland since the same period has been no less

remarkable. If the state of the country, as we have above described it from

authentic documents, be compared with what it is now, it will be found that

there are few countries which have accomplished so much within so short a

period. It is usual to cite the United States as furnishing the most

extraordinary instance of social progress in modem times. But America has

had the advantage of importing its civilization for the most part ready

made, whereas that of Scotland has been entirely her own creation. By nature

America is rich, and of boundless extent; whereas Scotland is by nature

poor, the greater part of her limited area consisting of sterile heath and

mountain. Little more than a century ago Scotland was considerably in the

rear of Ireland. It was a country almost without agriculture, without mines,

without fisheries, without shipping, without money, without roads. The

people were ill-fed, half barbarous, and habitually indolent. The colliers

and salters were veritable slaves, and were subject to be sold together with

the estates to which they belonged.

What do we find now? Praedial

slavery completely abolished; heritable jurisdictions at an end; the face of

the country entirely changed; its agriculture acknowledged to be the first

in the world; its mines and fisheries productive in the highest degree; its

banking a model of efficiency and public usefulness; its roads equal to the

best roads in England or in Europe. The people are active and energetic,

alike in education, in trade, in manufactures, in construction, in

invention. Watt's invention of the steam engine, and Symington's invention

of the steam-boat, proved a source of wealth and power, not only to their

own country, but to the world at large; while Telford, by his roads, bound

England and Scotland, before separated, firmly into one, and rendered the

union a source of wealth and strength to both.

At the same time, active and

powerful minds were occupied in extending the domain of knowledge,--Adam

Smith in Political Economy, Reid and Dugald Stewart in Moral Philosophy, and

Black and Robison in Physical Science. And thus Scotland, instead of being

one of the idlest and most backward countries in Europe, has, within the

compass of little more than a lifetime, issued in one of the most active,

contented, and prosperous,--exercising an amount of influence upon the

literature, science, political economy, and industry of modern times, out of

all proportion to the natural resources of its soil or the amount of its

population.

If we look for the causes of

this extraordinary social progress, we shall probably find the principal to

consist in the fact that Scotland, though originally poor as a country, was

rich in Parish schools, founded under the provisions of an Act passed by the

Scottish Parliament in the year 1696. It was there ordained "that there be a

school settled and established, and a schoolmaster appointed, in every

parish not already provided, by advice of the heritors and minister of the

parish." Common day-schools were accordingly provided and maintained

throughout the country for the education of children of all ranks and

conditions. The consequence was, that in the course of a few generations,

these schools, working steadily upon the minds of the young, all of whom

passed under the hands of the teachers, educated the population into a state

of intelligence and aptitude greatly in advance of their material

well-being; and it is in this circumstance, we apprehend, that the

explanation is to be found of the rapid start forward which the whole

country took, dating more particularly from the year 1745. Agriculture was

naturally the first branch of industry to exhibit signs of decided

improvement; to be speedily followed by like advances in trade, commerce,

and manufactures. Indeed, from that time the country never looked back, but

her progress went on at a constantly accelerated rate, issuing in results as

marvellous as they have probably been unprecedented.

Footnotes for Chapter VIII.

*[1] Romilly's

Autobiography,' ii. 22.

*[2] Statistical Account of

Scotland,' iii. 185.

*[3] The cas-chrom was a rude

combination of a lever for the removal of rocks, a spade to cut the earth,

and a foot-plough to turn it. We annex an illustration of this curious and

now obsolete instrument. It weighed about eighteen pounds. In working it,

the" upper part of the handle, to which the left hand was applied, reached

the workman's shoulder, and being slightly elevated, the point, shod with

iron, was pushed into the ground horizontally; the soil being turned over by

inclining the handle to the furrow side, at the same time making the heel

act as a fulcrum to raise the point of the instrument. In turning up

unbroken ground, it was first employed with the heel uppermost, with pushing

strokes to cut the breadth of the sward to be turned over; after which, it

was used horizontally as above described. We are indebted to a Parliamentary

Blue Book for the following representation of this interesting relic of

ancient agriculture. It is given in the appendix to the 'Ninth Report of the

Commissioners for Highland Roads and Bridges,' ordered by the House of

Commons to be printed, 19th April, 1821.

*[4] Anderson's 'Guide to the

Highlands and Islands of Scotland,' 3rd ed. p.48.

*[5] He was accompanied on

this tour by Colonel Dirom, with whom he returned to his house at Mount

Annan, in Dumfries. Telford says of him: "The Colonel seems to have roused

the county of Dumfries from the lethargy in which it has slumbered for

centuries. The map of the county, the mineralogical survey, the new roads,

the opening of lime works, the competition of ploughing, the improving

harbours, the building of bridges, are works which bespeak the exertions of

no common man."--Letter to Mr. Andrew. Little, dated Shrewsbury, 30th

November, 1801.

*[6] Ordered to be printed

5th of April, 1803.

*[7] 'Memorials of his Time,"

by Henry Cockburn, pp. 341-3.

*[8] 'Memoirs of the Life and

Writings of Sir John Sinclair, Barb,' vol. i., p. 339.

*[9] Extract of a letter from

a gentleman residing in Sunderland, quoted in 'Life of Telford,' p. 465.

*[10] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Salop, 18th February, 1803.

*[11] The names of Celtic

places are highly descriptive. Thus Craig-Ellachie literally means, the rock

of separation; Badenoch, bushy or woody; Cairngorm, the blue cairn; Lochinet,

the lake of nests; Balknockan, the town of knolls; Dalnasealg, the hunting

dale; Alt'n dater, the burn of the horn-blower; and so on.

*[12] Sir Thomas Dick Lauder

has vividly described the destructive character of the Spey-side inundations

in his capital book on the 'Morayshire Floods.'

*[13] 'Report of the

Commissioners on Highland Roads and Bridges.' Appendix to 'Life of Telford,'

p. 400. |