|

As surveyor for the county,

Telford was frequently called upon by the magistrates to advise them as to

the improvement of roads and the building or repair of bridges. His early

experience of bridge-building in his native district now proved of much

service to him, and he used often to congratulate himself, even when he had

reached the highest rank in his profession, upon the circumstances which had

compelled him to begin his career by working with his own hands. To be a

thorough judge of work, he held that a man must himself have been

practically engaged in it.

"Not only," he said, "are the

natural senses of seeing and feeling requisite in the examination of

materials, but also the practised eye, and the hand which has had experience

of the kind and qualities of stone, of lime, of iron, of timber, and even of

earth, and of the effects of human ingenuity in applying and combining all

these substances, are necessary for arriving at mastery in the profession;

for, how can a man give judicious directions unless he possesses personal

knowledge of the details requisite to effect his ultimate purpose in the

best and cheapest manner? It has happened to me more than once, when taking

opportunities of being useful to a young man of merit, that I have

experienced opposition in taking him from his books and drawings, and

placing a mallet, chisel, or trowel in his hand, till, rendered confident by

the solid knowledge which experience only can bestow, he was qualified to

insist on the due performance of workmanship, and to judge of merit in the

lower as well as the higher departments of a profession in which no kind or

degree of practical knowledge is superfluous."

The first bridge designed and

built under Telford's superintendence was one of no great magnitude, across

the river Severn at Montford, about four miles west of Shrewsbury. It was a

stone bridge of three elliptical arches, one of 58 feet and two of 55 feet

span each. The Severn at that point is deep and narrow, and its bed and

banks are of alluvial earth. It was necessary to make the foundations very

secure, as the river is subject to high floods; and this was effectuality

accomplished by means of coffer-dams. The building was substantially

executed in red sandstone, and proved a very serviceable bridge, forming

part of the great high road from Shrewsbury into Wales. It was finished in

the year 1792.

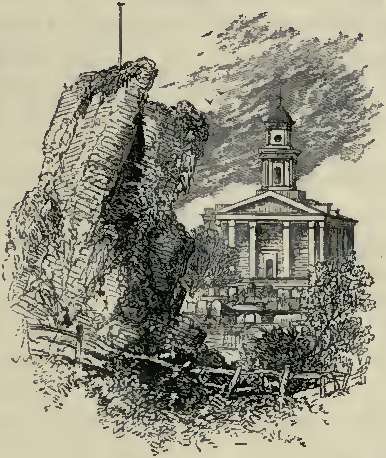

In the same year, we find

Telford engaged as an architect in preparing the designs and superintending

the construction of the new parish church of St. Mary Magdalen at

Bridgenorth. It stands at the end of Castle Street, near to the old ruined

fortress perched upon the bold red sandstone bluff on which the upper part

of the town is built. The situation of the church is very fine, and an

extensive view of the beautiful vale of the Severn is obtained from it.

Telford's design is by no means striking; "being," as he said, "a regular

Tuscan elevation; the inside is as regularly Ionic: its only merit is

simplicity and uniformity; it is surmounted by a Doric tower, which contains

the bells and a clock." A graceful Gothic church would have been more

appropriate to the situation, and a much finer object in the landscape; but

Gothic was not then in fashion--only a mongrel mixture of many styles,

without regard to either purity or gracefulness. The church, however, proved

comfortable and commodious, and these were doubtless the points to which the

architect paid most attention.

St. Mary Magdalen, Bridgenorth.

His completion of the church

at Bridgenorth to the satisfaction of the inhabitants, brought Telford a

commission, in the following year, to erect a similar edifice at

Coalbrookdale. But in the mean time, to enlarge his knowledge and increase

his acquaintance with the best forms of architecture, he determined to make

a journey to London and through some of the principal towns of the south of

England. He accordingly visited Gloucester, Worcester, and Bath, remaining

several days in the last-mentioned city. He was charmed beyond expression by

his journey through the manufacturing districts of Gloucestershire, more

particularly by the fine scenery of the Vale of Stroud. The whole seemed to

him a smiling scene of prosperous industry and middle-class comfort.

But passing out of this

"Paradise," as he styled it, another stage brought him into a region the

very opposite. "We stopped," says he, "at a little alehouse on the side of a

rough hill to water the horses, and lo! the place was full of drunken

blackguards, bellowing out 'Church and King!' A poor ragged German Jew

happened to come up, whom those furious loyalists had set upon and accused

of being a Frenchman in disguise. He protested that he was only a poor

German who 'cut de corns,' and that all he wanted was to buy a little bread

and cheese. Nothing would serve them but they must carry him before the

Justice. The great brawny fellow of a landlord swore he should have nothing

in his house, and, being a, constable, told him that he would carry him to

gaol. I interfered, and endeavoured to pacify the assailants of the poor

man; when suddenly the landlord, snatching up a long knife, sliced off about

a pound of raw bacon from a ham which hung overhead, and, presenting it to

the Jew, swore that if he did not swallow it down at once he should not be

allowed to go. The man was in a worse plight than ever. He said he was a

'poor Shoe,' and durst not eat that. In the midst of the uproar, Church and

King were forgotten, and eventually I prevailed upon the landlord to accept

from me as much as enabled poor little Moses to get his meal of bread and

cheese; and by the time the coach started they all seemed perfectly

reconciled." *[1] Telford was much gratified by his visit to Bath, and

inspected its fine buildings with admiration. But he thought that Mr. Wood,

who, he says, "created modern Bath," had left no worthy successor. In the

buildings then in progress he saw clumsy designers at work, "blundering

round about a meaning"--if, indeed, there was any meaning at all in their

designs, which he confessed he failed to see. From Bath he went to London by

coach, making the journey in safety, "although," he says, the collectors had

been doing duty on Hounslow Heath." During his stay in London he carefully

examined the principal public buildings by the light of the experience which

he had gained since he last saw them. He also spent a good deal of his time

in studying rare and expensive works on architecture--the use of which he

could not elsewhere procure-- at the libraries of the Antiquarian Society

and the British Museum. There he perused the various editions of Vitruvius

and Palladio, as well as Wren's 'Parentalia.' He found a rich store of

ancient architectural remains in the British Museum, which he studied with

great care: antiquities from Athens, Baalbec, Palmyra, and Herculaneum; "so

that," he says, "what with the information I was before possessed of, and

that which I have now accumulated, I think I have obtained a tolerably good

general notion of architecture."

From London he proceeded to

Oxford, where he carefully inspected its colleges and churches, afterwards

expressing the great delight and profit which he had derived from his visit.

He was entertained while there by Mr. Robertson, an eminent mathematician,

then superintending the publication of an edition of the works of

Archimedes. The architectural designs of buildings that most pleased him

were those of Dr. Aldrich, Dean of Christchurch about the time of Sir

Christopher Wren. He tore himself from Oxford with great regret, proceeding

by Birmingham on his way home to Shrewsbury: "Birmingham," he says, "famous

for its buttons and locks, its ignorance and barbarism--its prosperity

increases with the corruption of taste and morals. Its nicknacks, hardware,

and gilt gimcracks are proofs of the former; and its locks and bars, and the

recent barbarous conduct of its populace,*[2] are evidences of the

latter." His principal object in visiting the place was to call upon a

stained glass-maker respecting a window for the new church at Bridgenorth.

On his return to Shrewsbury,

Telford proposed to proceed with his favourite study of architecture; but

this, said he, "will probably be very slowly, as I must attend to my every

day employment," namely, the superintendence of the county road and bridge

repairs, and the direction of the convicts' labour. "If I keep my health,

however," he added, "and have no unforeseen hindrance, it shall not be

forgotten, but will be creeping on by degrees." An unforeseen circumstance,

though not a hindrance, did very shortly occur, which launched Telford upon

a new career, for which his unremitting study, as well as his carefully

improved experience, eminently fitted him: we refer to his appointment as

engineer to the Ellesmere Canal Company.

The conscientious carefulness

with which Telford performed the duties entrusted to him, and the skill with

which he directed the works placed under his charge, had secured the general

approbation of the gentlemen of the county. His straightforward and

outspoken manner had further obtained for him the friendship of many of

them. At the meetings of quarter-sessions his plans had often to encounter

considerable opposition, and, when called upon to defend them, he did so

with such firmness, persuasiveness, and good temper, that he usually carried

his point. "Some of the magistrates are ignorant," he wrote in 1789, "and

some are obstinate: though I must say that on the whole there is a very

respectable bench, and with the sensible part I believe I am on good terms."

This was amply proved some four years later, when it became necessary to

appoint an engineer to the Ellesmere Canal, on which occasion the

magistrates, who were mainly the promoters of the undertaking, almost

unanimously solicited their Surveyor to accept the office.

Indeed, Telford had become a

general favourite in the county. He was cheerful and cordial in his manner,

though somewhat brusque. Though now thirty-five years old, he had not lost

the humorousness which had procured for him the sobriquet of "Laughing Tam."

He laughed at his own jokes as well as at others. He was spoken of as

jolly--a word then much more rarely as well as more choicely used than it is

now. Yet he had a manly spirit, and was very jealous of his independence.

All this made him none the less liked by free-minded men. Speaking of the

friendly support which he had throughout received from Mr. Pulteney, he

said, "His good opinion has always been a great satisfaction to me; and the

more so, as it has neither been obtained nor preserved by deceit, cringing,

nor flattery. On the contrary, I believe I am almost the only man that

speaks out fairly to him, and who contradicts him the most. In fact, between

us, we sometimes quarrel like tinkers; but I hold my ground, and when he

sees I am right he quietly gives in."

Although Mr. Pulteney's

influence had no doubt assisted Telford in obtaining the appointment of

surveyor, it had nothing to do with the unsolicited invitation which now

emanated from the county gentlemen. Telford was not even a candidate for the

engineership, and had not dreamt of offering himself, so that the proposal

came upon him entirely by surprise. Though he admitted he had

self-confidence, he frankly confessed that he had not a sufficient amount of

it to justify him in aspiring to the office of engineer to one of the most

important undertakings of the day. The following is his own account of the

circumstance:--

"My literary project*[3] is

at present at a stand, and may be retarded for some time to come, as I was

last Monday appointed sole agent, architect, and engineer to the canal which

is projected to join the Mersey, the Dee, and the Severn. It is the greatest

work, I believe, now in hand in this kingdom, and will not be completed for

many years to come. You will be surprised that I have not mentioned this to

you before; but the fact is that I had no idea of any such appointment until

an application was made to me by some of the leading gentlemen, and I was

appointed, though many others had made much interest for the place. This

will be a great and laborious undertaking, but the line which it opens is

vast and noble; and coming as the appointment does in this honourable way, I

thought it too great a opportunity to be neglected, especially as I have

stipulated for, and been allowed, the privilege of carrying on my

architectural profession. The work will require great labour and exertions,

but it is worthy of them all."*[4] Telford's appointment was duly confirmed

by the next general meeting of the shareholders of the Ellesmere Canal. An

attempt was made to get up a party against him, but it failed. "I am

fortunate," he said, "in being on good terms with most of the leading men,

both of property and abilities; and on this occasion I had the decided

support of the great John Wilkinson, king of the ironmasters, himself a

host. I travelled in his carriage to the meeting, and found him much

disposed to be friendly."*[5] The salary at which Telford was engaged was

500L. a year, out of which he had to pay one clerk and one confidential

foreman, besides defraying his own travelling expenses. It would not appear

that after making these disbursements much would remain for Telford's own

labour; but in those days engineers were satisfied with comparatively small

pay, and did not dream of making large fortunes.

Though Telford intended to

continue his architectural business, he decided to give up his county

surveyorship and other minor matters, which, he said, "give a great deal of

very unpleasant labour for very little profit; in short they are like the

calls of a country surgeon." One part of his former business which he did

not give up was what related to the affairs of Mr. Pulteney and Lady Bath,

with whom he continued on intimate and friendly terms. He incidentally

mentions in one of his letters a graceful and charming act of her Ladyship.

On going into his room one day he found that, before setting out for Buxton,

she had left upon his table a copy of Ferguson's 'Roman Republic,' in three

quarto volumes, superbly bound and gilt.

He now looked forward with

anxiety to the commencement of the canal, the execution of which would

necessarily call for great exertion on his part, as well as unremitting

attention and industry; "for," said he, "besides the actual labour which

necessarily attends so extensive a public work, there are contentions,

jealousies, and prejudices, stationed like gloomy sentinels from one

extremity of the line to the other. But, as I have heard my mother say that

an honest man might look the Devil in the face without being afraid, so we

must just trudge along in the old way."*[6]

Footnotes for Chapter V.

*[1] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Shrewsbury, 10th March, 1793

*[2] Referring to the burning

of Dr. Priestley's library.

*[3] The preparation of some

translations from Buchanan which he had contemplated.

*[4] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Shrewsbury, 29th September, 1793.

*[5] John Wilkinson and his

brother William were the first of the great class of ironmasters. They

possessed iron forges at Bersham near Chester, at Bradley, Brimbo, Merthyr

Tydvil, and other places; and became by far the largest iron manufacturers

of their day. For notice of them see 'Lives of Boulton and Watt,' p. 212.

*[6] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Shrewsbury, 3rd November, 1793. |