|

Mr. Pulteney, member for

Shrewsbury, was the owner of extensive estates in that neighbourhood by

virtue of his marriage with the niece of the last Earl of Bath. Having

resolved to fit up the Castle there as a residence, he bethought him of the

young Eskdale mason, who had, some years before, advised him as to the

repairs of the Johnstone mansion at Wester Hall. Telford was soon found, and

engaged to go down to Shrewsbury to superintend the necessary alterations.

Their execution occupied his attention for some time, and during their

progress he was so fortunate as to obtain the appointment of Surveyor of

Public Works for the county of Salop, most probably through the influence of

his patron. Indeed, Telford was known to be so great a favourite with Mr.

Pulteney that at Shrewsbury he usually went by the name of "Young Pulteney."

Much of his attention was

from this time occupied with the surveys and repairs of roads, bridges, and

gaols, and the supervision of all public buildings under the control of the

magistrates of the county. He was also frequently called upon by the

corporation of the borough of Shrewsbury to furnish plans for the

improvement of the streets and buildings of that fine old town; and many

alterations were carried out under his direction during the period of his

residence there.

While the Castle repairs were

in course of execution, Telford was called upon by the justices to

superintend the erection of a new gaol, the plans for which had already been

prepared and settled. The benevolent Howard, who devoted himself with such

zeal to gaol improvement, on hearing of the intentions of the magistrates,

made a visit to Shrewsbury for the purpose of examining the plans; and the

circumstance is thus adverted to by Telford in one of his letters to his

Eskdale correspondent:--"About ten days ago I had a visit from the

celebrated John Howard, Esq. I say I, for he was on his tour of gaols and

infirmaries; and those of Shrewsbury being both under my direction, this

was, of course, the cause of my being thus distinguished. I accompanied him

through the infirmary and the gaol. I showed him the plans of the proposed

new buildings, and had much conversation with him on both subjects. In

consequence of his suggestions as to the former, I have revised and amended

the plans, so as to carry out a thorough reformation; and my alterations

having been approved by a general board, they have been referred to a

committee to carry out. Mr. Howard also took objection to the plan of the

proposed gaol, and requested me to inform the magistrates that, in his

opinion, the interior courts were too small, and not sufficiently

ventilated; and the magistrates, having approved his suggestions, ordered

the plans to be amended accordingly. You may easily conceive how I enjoyed

the conversation of this truly good man, and how much I would strive to

possess his good opinion. I regard him as the guardian angel of the

miserable. He travels into all parts of Europe with the sole object of doing

good, merely for its own sake, and not for the sake of men's praise. To give

an instance of his delicacy, and his desire to avoid public notice, I may

mention that, being a Presbyterian, he attended the meeting-house of that

denomination in Shrewsbury on Sunday morning, on which occasion I

accompanied him; but in the afternoon he expressed a wish to attend another

place of worship, his presence in the town having excited considerable

curiosity, though his wish was to avoid public recognition. Nay, more, he

assures me that he hates travelling, and was born to be a domestic man. He

never sees his country-house but he says within himself, 'Oh! might I but

rest here, and never more travel three miles from home; then should I be

happy indeed!' But he has become so committed, and so pledged himself to his

own conscience to carry out his great work, that he says he is doubtful

whether he will ever be able to attain the desire of his heart--life at

home. He never dines out, and scarcely takes time to dine at all: he says he

is growing old, and has no time to lose. His manner is simplicity itself.

Indeed, I have never yet met so noble a being. He is going abroad again

shortly on one of his long tours of mercy."*[1] The journey to which Telford

here refers was Howard's last. In the following year he left England to

return no more; and the great and good man died at Cherson, on the shores of

the Black Sea, less than two years after his interview with the young

engineer at Shrewsbury.

Telford writes to his

Langholm friend at the same time that he is working very hard, and studying

to improve himself in branches of knowledge in which he feels himself

deficient. He is practising very temperate habits: for half a year past he

has taken to drinking water only, avoiding all sweets, and eating no "nick-nacks."

He has "sowens and milk,' (oatmeal flummery) every night for his supper. His

friend having asked his opinion of politics, he says he really knows nothing

about them; he had been so completely engrossed by his own business that he

has not had time to read even a newspaper. But, though an ignoramus in

politics, he has been studying lime, which is more to his purpose. If his

friend can give him any information about that, he will promise to read a

newspaper now and then in the ensuing session of Parliament, for the purpose

of forming some opinion of politics: he adds, however, "not if it interfere

with my business--mind that!', His friend told him that he proposed

translating a system of chemistry. "Now you know," wrote Telford, "that I am

chemistry mad; and if I were near you, I would make you promise to

communicate any information on the subject that you thought would be of

service to your friend, especially about calcareous matters and the mode of

forming the best composition for building with, as well above as below

water. But not to be confined to that alone, for you must know I have a book

for the pocket,*[2] which I always carry with me, into which I have

extracted the essence of Fourcroy's Lectures, Black on Quicklime, Scheele's

Essays, Watson's Essays, and various points from the letters of my respected

friend Dr. Irving.*[3] So much for chemistry. But I have also crammed into

it facts relating to mechanics, hydrostatics, pneumatics, and all manner of

stuff, to which I keep continually adding, and it will be a charity to me if

you will kindly contribute your mite."*[4] He says it has been, and will

continue to be, his aim to endeavour to unite those "two frequently jarring

pursuits, literature and business;" and he does not see why a man should be

less efficient in the latter capacity because he has well informed, stored,

and humanized his mind by the cultivation of letters. There was both good

sense and sound practical wisdom in this view of Telford.

While the gaol was in course

of erection, after the improved plans suggested by Howard, a variety of

important matters occupied the county surveyor's attention. During the

summer of 1788 he says he is very much occupied, having about ten different

jobs on hand: roads, bridges, streets, drainage-works, gaol, and infirmary.

Yet he had time to write verses, copies of which he forwarded to his Eskdale

correspondent, inviting his criticism. Several of these were elegiac lines,

somewhat exaggerated in their praises of the deceased, though doubtless

sincere. One poem was in memory of George Johnstone, Esq., a member of the

Wester Hall family, and another on the death of William Telford, an Eskdale

farmer's son, an intimate friend and schoolfellow of our engineer.*[5]

These, however, were but the votive offerings of private friendship, persons

more immediately about him knowing nothing of his stolen pleasures in

versemaking. He continued to be shy of strangers, and was very "nice," as he

calls it, as to those whom he admitted to his bosom.

Two circumstances of

considerable interest occurred in the course of the same year (1788), which

are worthy of passing notice. The one was the fall of the church of St.

Chad's, at Shrewsbury; the other was the discovery of the ruins of the Roman

city of Uriconium, in the immediate neighbourhood. The church of St. Chad's

was about four centuries old, and stood greatly in need of repairs. The roof

let in the rain upon the congregation, and the parish vestry met to settle

the plans for mending it; but they could not agree about the mode of

procedure. In this emergency Telford was sent for, and requested to advise

what was best to he done. After a rapid glance at the interior, which was in

an exceedingly dangerous state, he said to the churchwardens, "Gentlemen,

we'll consult together on the outside, if you please." He found that not

only the roof but the walls of the church were in a most decayed state. It

appeared that, in consequence of graves having been dug in the loose soil

close to the shallow foundation of the north-west pillar of the tower, it

had sunk so as to endanger the whole structure. "I discovered," says he,

"that there were large fractures in the walls, on tracing which I found that

the old building was in a most shattered and decrepit condition, though

until then it had been scarcely noticed. Upon this I declined giving any

recommendation as to the repairs of the roof unless they would come to the

resolution to secure the more essential parts, as the fabric appeared to me

to be in a very alarming condition. I sent in a written report to the same

effect." *[6]

The parish vestry again met,

and the report was read; but the meeting exclaimed against so extensive a

proposal, imputing mere motives of self-interest to the surveyor. "Popular

clamour," says Telford, "overcame my report. 'These fractures,' exclaimed

the vestrymen, 'have been there from time immemorial;' and there were some

otherwise sensible persons, who remarked that professional men always wanted

to carve out employment for themselves, and that the whole of the necessary

repairs could be done at a comparatively small expense."*[7] The vestry then

called in another person, a mason of the town, and directed him to cut away

the injured part of a particular pillar, in order to underbuild it. On the

second evening after the commencement of the operations, the sexton was

alarmed by a fail of lime-dust and mortar when he attempted to toll the

great bell, on which he immediately desisted and left the church. Early next

morning (on the 9th of July), while the workmen were waiting at the church

door for the key, the bell struck four, and the vibration at once brought

down the tower, which overwhelmed the nave, demolishing all the pillars

along the north side, and shattering the rest. "The very parts I had pointed

out," says Telford, "were those which gave way, and down tumbled the tower,

forming a very remarkable ruin, which astonished and surprised the vestry,

and roused them from their infatuation, though they have not yet recovered

from the shock."*[8]

The other circumstance to

which we have above referred was the discovery of the Roman city of

Uriconium, near Wroxeter, about five miles from Shrewsbury, in the year

1788. The situation of the place is extremely beautiful, the river Severn

flowing along its western margin, and forming a barrier against what were

once the hostile districts of West Britain. For many centuries the dead city

had slept under the irregular mounds of earth which covered it, like those

of Mossul and Nineveh. Farmers raised heavy crops of turnips and grain from

the surface and they scarcely ever ploughed or harrowed the ground without

turning up Roman coins or pieces of pottery. They also observed that in

certain places the corn was more apt to be scorched in dry weather than in

others--a sure sign to them that there were ruins underneath; and their

practice, when they wished to find stones for building, was to set a mark

upon the scorched places when the corn was on the ground, and after harvest

to dig down, sure of finding the store of stones which they wanted for

walls, cottages, or farm-houses. In fact, the place came to be regarded in

the light of a quarry, rich in ready-worked materials for building purposes.

A quantity of stone being wanted for the purpose of erecting a blacksmith's

shop, on digging down upon one of the marked places, the labourers came upon

some ancient works of a more perfect appearance than usual. Curiosity was

excited --antiquarians made their way to the spot--and lo! they pronounced

the ruins to be neither more nor less than a Roman bath, in a remarkably

perfect state of preservation. Mr. Telford was requested to apply to Mr.

Pulteney, the lord of the manor, to prevent the destruction of these

interesting remains, and also to permit the excavations to proceed, with a

view to the buildings being completely explored. This was readily granted,

and Mr. Pulteney authorised Telford himself to conduct the necessary

excavations at his expense. This he promptly proceeded to do, and the result

was, that an extensive hypocaust apartment was brought to light, with baths,

sudatorium, dressing-room, and a number of tile pillars --all forming parts

of a Roman floor--sufficiently perfect to show the manner in which the

building had been constructed and used.*[9] Among Telford's less agreeable

duties about the same time was that of keeping the felons at work. He had to

devise the ways and means of employing them without risk of their escaping,

which gave him much trouble and anxiety. "Really," he said, "my felons are a

very troublesome family. I have had a great deal of plague from them, and I

have not yet got things quite in the train that I could wish. I have had a

dress made for them of white and brown cloth, in such a way that they are

pye-bald. They have each a light chain about one leg. Their allowance in

food is a penny loaf and a halfpenny worth of cheese for breakfast; a penny

loaf, a quart of soup, and half a pound of meat for dinner; and a penny loaf

and a halfpenny worth of cheese for supper; so that they have meat and

clothes at all events. I employ them in removing earth, serving masons or

bricklayers, or in any common labouring work on which they can be employed;

during which time, of course, I have them strictly watched."

Much more pleasant was his

first sight of Mrs. Jordan at the Shrewsbury theatre, where he seems to have

been worked up to a pitch of rapturous enjoyment. She played for six nights

there at the race time, during which there were various other'

entertainments. On the second day there was what was called an Infirmary

Meeting, or an assemblage of the principal county gentlemen in the

infirmary, at which, as county surveyor, Telford was present. They proceeded

thence to church to hear a sermon preached for the occasion; after which

there was a dinner, followed by a concert. He attended all. The sermon was

preached in the new pulpit, which had just been finished after his design,

in the Gothic style; and he confidentially informed his Langholm

correspondent that he believed the pulpit secured greater admiration than

the sermon, With the concert he was completely disappointed, and he then

became convinced that he had no ear for music. Other people seemed very much

pleased; but for the life of him he could make nothing of it. The only

difference that he recognised between one tune and another was that there

was a difference in the noise. "It was all very fine," he said, "I have no

doubt; but I would not give a song of Jock Stewart *[10] for the whole of

them. The melody of sound is thrown away upon me. One look, one word of Mrs.

Jordan, has more effect upon me than all the fiddlers in England. Yet I sat

down and tried to be as attentive as any mortal could be. I endeavoured, if

possible, to get up an interest in what was going on; but it was all of no

use. I felt no emotion whatever, excepting only a strong inclination to go

to sleep. It must be a defect; but it is a fact, and I cannot help it. I

suppose my ignorance of the subject, and the want of musical experience in

my youth, may be the cause of it."*[11] Telford's mother was still living in

her old cottage at The Crooks. Since he had parted from her, he had written

many printed letters to keep her informed of his progress; and he never

wrote to any of his friends in the dale without including some message or

other to his mother. Like a good and dutiful son, he had taken care out of

his means to provide for her comfort in her declining years. "She has been a

good mother to me," he said, "and I will try and be a good son to her." In a

letter written from Shrewsbury about this time, enclosing a ten pound note,

seven pounds of which were to be given to his mother, he said, "I have from

time to time written William Jackson [his cousin] and told him to furnish

her with whatever she wants to make her comfortable; but there may be many

little things she may wish to have, and yet not like to ask him for. You

will therefore agree with me that it is right she should have a little cash

to dispose of in her own way.... I am not rich yet; but it will ease my mind

to set my mother above the fear of want. That has always been my first

object; and next to that, to be the somebody which you have always

encouraged me to believe I might aspire to become. Perhaps after all there

may be something in it!" *[12] He now seems to have occupied much of his

leisure hours in miscellaneous reading. Among the numerous books which he

read, he expressed the highest admiration for Sheridan's 'Life of Swift.'

But his Langholm friend, who was a great politician, having invited his

attention to politics, Telford's reading gradually extended in that

direction. Indeed the exciting events of the French Revolution then tended

to make all men more or less politicians. The capture of the Bastille by the

people of Paris in 1789 passed like an electric thrill through Europe. Then

followed the Declaration of Rights; after which, in the course of six

months, all the institutions which had before existed in France were swept

away, and the reign of justice was fairly inaugurated upon earth!

In the spring of 1791 the

first part of Paine's 'Rights of Man' appeared, and Telford, like many

others, read it, and was at once carried away by it. Only a short time

before, he had admitted with truth that he knew nothing of politics; but no

sooner had he read Paine than he felt completely enlightened. He now

suddenly discovered how much reason he and everybody else in England had for

being miserable. While residing at Portsmouth, he had quoted to his Langholm

friend the lines from Cowper's 'Task,' then just published, beginning

"Slaves cannot breathe in England;" but lo! Mr. Paine had filled his

imagination with the idea that England was nothing but a nation of bondmen

and aristocrats. To his natural mind, the kingdom had appeared to be one in

which a man had pretty fair play, could think and speak, and do the thing he

would,-- tolerably happy, tolerably prosperous, and enjoying many blessings.

He himself had felt free to labour, to prosper, and to rise from manual to

head work. No one had hindered him; his personal liberty had never been

interfered with; and he had freely employed his earnings as he thought

proper. But now the whole thing appeared a delusion. Those rosy-cheeked old

country gentlemen who came riding into Shrewsbury to quarter sessions, and

were so fond of their young Scotch surveyor occupying themselves in building

bridges, maintaining infirmaries, making roads, and regulating gaols-- those

county magistrates and members of parliament, aristocrats all, were the very

men who, according to Paine, were carrying the country headlong to ruin!

If Telford could not offer an

opinion on politics before, because he "knew nothing about them," he had now

no such difficulty. Had his advice been asked about the foundations of a

bridge, or the security of an arch, he would have read and studied much

before giving it; he would have carefully inquired into the chemical

qualities of different kinds of lime--into the mechanical principles of

weight and resistance, and such like; but he had no such hesitation in

giving an opinion about the foundations of a constitution of more than a

thousand years' growth. Here, like other young politicians, with Paine's

book before him, he felt competent to pronounce a decisive judgment at once.

"I am convinced," said he, writing to his Langholm friend, "that the

situation of Great Britain is such, that nothing short of some signal

revolution can prevent her from sinking into bankruptcy, slavery, and

insignificancy." He held that the national expenditure was so enormous,*[13]

arising from the corrupt administration of the country, that it was

impossible the "bloated mass" could hold together any longer; and as he

could not expect that "a hundred Pulteneys," such as his employer, could be

found to restore it to health, the conclusion he arrived at was that ruin

was "inevitable."*[14] Notwithstanding the theoretical ruin of England which

pressed so heavy on his mind at this time, we find Telford strongly

recommending his correspondent to send any good wrights he could find in his

neighbourhood to Bath, where they would be enabled to earn twenty shillings

or a guinea a week at piece-work-- the wages paid at Langholm for similar

work being only about half those amounts.

In the same letter in which

these observations occur, Telford alluded to the disgraceful riots at

Birmingham, in the course of which Dr. Priestley's house and library were

destroyed. As the outrages were the work of the mob, Telford could not

charge the aristocracy with them; but with equal injustice he laid the blame

at the door of "the clergy," who had still less to do with them, winding up

with the prayer, "May the Lord mend their hearts and lessen their incomes!"

Fortunately for Telford, his

intercourse with the townspeople of Shrewsbury was so small that his views

on these subjects were never known; and we very shortly find him employed by

the clergy themselves in building for them a new church in the town of

Bridgenorth. His patron and employer, Mr. Pulteney, however, knew of his

extreme views, and the knowledge came to him quite accidentally. He found

that Telford had made use of his frank to send through the post a copy of

Paine's 'Rights of Man' to his Langholm correspondent,*[15] where the

pamphlet excited as much fury in the minds of some of the people of that

town as it had done in that of Telford himself. The "Langholm patriots

"broke out into drinking revolutionary toasts at the Cross, and so disturbed

the peace of the little town that some of them were confined for six weeks

in the county gaol.

Mr. Pulteney was very

indignant at the liberty Telford had taken with his frank, and a rupture

between them seemed likely to ensue; but the former was forgiving, and the

matter went no further. It is only right to add, that as Telford grew older

and wiser, he became more careful in jumping at conclusions on political

topics. The events which shortly occurred in France tended in a great

measure to heal his mental distresses as to the future of England. When the

"liberty" won by the Parisians ran into riot, and the "Friends of Man"

occupied themselves in taking off the heads of those who differed from them,

he became wonderfully reconciled to the enjoyment of the substantial freedom

which, after all, was secured to him by the English Constitution. At the

same time, he was so much occupied in carrying out his important works, that

he found but little time to devote either to political speculation or to

versemaking.

While living at Shrewsbury,

he had his poem of 'Eskdale' reprinted for private circulation. We have also

seen several MS. verses by him, written about the same period, which do not

appear ever to have been printed. One of these--the best--is entitled

'Verses to the Memory of James Thomson, author of "Liberty, a poem;"'

another is a translation from Buchanan, 'On the Spheres;' and a third,

written in April, 1792, is entitled 'To Robin Burns, being a postscript to

some verses addressed to him on the establishment of an Agricultural Chair

in Edinburgh.' It would unnecessarily occupy our space to print these

effusions; and, to tell the truth, they exhibit few if any indications of

poetic power. No amount of perseverance will make a poet of a man in whom

the divine gift is not born. The true line of Telford's genius lay in

building and engineering, in which direction we now propose to follow him.

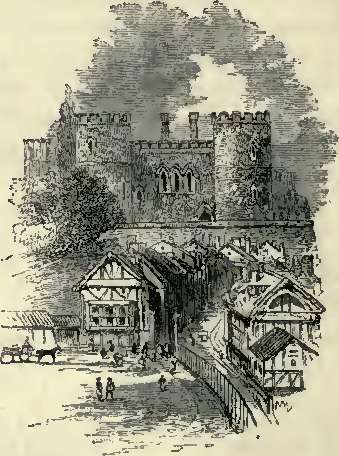

Shrewsbury Castle

Footnotes for Chapter IV.

*[1] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Shrewsbury Castle, 21st Feb., 1788.

*[2] This practice of noting

down information, the result of reading and observation, was continued by

Mr. Telford until the close of his life; his last pocket memorandum book,

containing a large amount of valuable information on mechanical subjects--a

sort of engineer's vade mecum--being printed in the appendix to the 4to.

'Life of Telford' published by his executors in 1838, pp. 663-90.

*[3] A medical man, a native

of Eskdale, of great promise, who died comparatively young.

*[4] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm.

*[5] It would occupy

unnecessary space to cite these poems. The following, from the verses in

memory of William Telford, relates to schoolboy days, After alluding to the

lofty Fell Hills, which formed part of the sheep farm of his deceased

friend's father, the poet goes on to say:

"There 'mongst those rocks

I'll form a rural seat,

And plant some ivy with its moss compleat;

I'll benches form of fragments from the stone,

Which, nicely pois'd, was by our hands o'erthrown,--

A simple frolic, but now dear to me,

Because, my Telford, 'twas performed with thee.

There, in the centre, sacred to his name,

I'll place an altar, where the lambent flame

Shall yearly rise, and every youth shall join

The willing voice, and sing the enraptured line.

But we, my friend, will often steal away

To this lone seat, and quiet pass the day;

Here oft recall the pleasing scenes we knew

In early youth, when every scene was new,

When rural happiness our moments blest,

And joys untainted rose in every breast."

*[6] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated 16th July, 1788.

*[7] Ibid.

*[8] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated 16th July, 1788.

*[9] The discovery formed the

subject of a paper read before the Society of Antiquaries in London on the

7th of May, 1789, published in the 'Archaeologia,' together with a drawing

of the remains supplied by Mr. Telford.

*[10] An Eskdale crony. His

son, Colonel Josias Stewart, rose to eminence in the East India Company's

service, having been for many years Resident at Gwalior and Indore.

*[11] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated 3rd Sept. 1788.

*[12] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated Shrewsbury, 8th October, 1789.

*[13] It was then under

seventeen millions sterling, or about a fourth of what it is now.

*[14] Letter to Mr. Andrew

Little, Langholm, dated 28th July, 1791.

*[15] The writer of a memoir

of Telford, in the 'Encyclopedia Britannica,' says:--"Andrew Little kept a

private and very small school at Langholm. Telford did not neglect to send

him a copy of Paine's 'Rights of Man;' and as he was totally blind, he

employed one of his scholars to read it in the evenings. Mr. Little had

received an academical education before he lost his sight; and, aided by a

memory of uncommon powers, he taught the classics, and particularly Greek,

with much higher reputation than any other schoolmaster within a pretty

extensive circuit. Two of his pupils read all the Iliad, and all or the

greater part of Sophocles. After hearing a long sentence of Greek or Latin

distinctly recited, he could generally construe and translate it with little

or no hesitation. He was always much gratified by Telford's visits, which

were not infrequent, to his native district." |