|

The progress made in the

improvement of the roads throughout England was exceedingly slow. Though

some of the main throughfares were mended so as to admit of stage-coach

travelling at the rate of from four to six miles an hour, the less

frequented roads continued to be all but impassable. Travelling was still

difficult, tedious, and dangerous. Only those who could not well avoid it

ever thought of undertaking a journey, and travelling for pleasure was out

of the question. A writer in the 'Gentleman's Magazine' in 1752 says that a

Londoner at that time would no more think of travelling into the west of

England for pleasure than of going to Nubia.

But signs of progress were

not awanting. In 1749 Birmingham started a stage-coach, which made the

journey to London in three days.*[1] In 1754 some enterprising Manchester

men advertised a "flying coach" for the conveyance of passengers between

that town and the metropolis; and, lest they should be classed with

projectors of the Munchausen kind, they heralded their enterprise with this

statement: "However incredible it may appear, this coach will actually

(barring accidents) arrive in London in four days and a half after leaving

Manchester!"

Fast coaches were also

established on several of the northern roads, though not with very

extraordinary results as to speed. When John Scott, afterwards Lord

Chancellor Eldon, travelled from Newcastle to Oxford in 1766, he mentions

that he journeyed in what was denominated "a fly," because of its rapid

travelling; yet he was three or four days and nights on the road. There was

no such velocity, however, as to endanger overturning or other mischief. On

the panels of the coach were painted the appropriate motto of Sat cito si

sat bene--quick enough if well enough--a motto which the future Lord

Chancellor made his own.*[2]

The journey by coach between

London and Edinburgh still occupied six days or more, according to the state

of the weather. Between Bath or Birmingham and London occupied between two

and three days as late as 1763. The road across Hounslow Heath was so bad,

that it was stated before a Parliamentary Committee that it was frequently

known to be two feet deep in mud. The rate of travelling was about six and a

half miles an hour; but the work was so heavy that it "tore the horses'

hearts out," as the common saying went, so that they only lasted two or

three years.

When the Bath road became

improved, Burke was enabled, in the summer of 1774, to travel from London to

Bristol, to meet the electors there, in little more than four and twenty

hours; but his biographer takes care to relate that he "travelled with

incredible speed." Glasgow was still ten days' distance from the metropolis,

and the arrival of the mail there was so important an event that a gun was

fired to announce its coming in. Sheffield set up a "flying machine on steel

springs" to London in 1760: it "slept" the first night at the Black Man's

Head Inn, Nottingham; the second at the Angel, Northampton; and arrived at

the Swan with Two Necks, Lad-lane, on the evening of the third day. The fare

was 1L. l7s., and 14 lbs. of luggage was allowed. But the principal part of

the expense of travelling was for living and lodging on the road, not to

mention the fees to guards and drivers.

Though the Dover road was

still one of the best in the kingdom, the Dover flying-machine, carrying

only four passengers, took a long summer's day to perform the journey. It

set out from Dover at four o'clock in the morning, breakfasted at the Red

Lion, Canterbury, and the passengers ate their way up to town at various

inns on the road, arriving in London in time for supper. Smollett complained

of the innkeepers along that route as the greatest set of extortioners in

England. The deliberate style in which journeys were performed may be

inferred from the circumstance that on one occasion, when a quarrel took

place between the guard and a passenger, the coach stopped to see them fight

it out on the road.

Foreigners who visited

England were peculiarly observant of the defective modes of conveyance then

in use. Thus, one Don Manoel Gonzales, a Portuguese merchant, who travelled

through Great Britain, in 1740, speaking of Yarmouth, says, "They have a

comical way of carrying people all over the town and from the seaside, for

six pence. They call it their coach, but it is only a wheel-barrow, drawn by

one horse, without any covering." Another foreigner, Herr Alberti, a

Hanoverian professor of theology, when on a visit to Oxford in 1750,

desiring to proceed to Cambridge, found there was no means of doing so

without returning to London and there taking coach for Cambridge. There was

not even the convenience of a carrier's waggon between the two universities.

But the most amusing account of an actual journey by stage-coach that we

know of, is that given by a Prussian clergyman, Charles H. Moritz, who thus

describes his adventures on the road between Leicester and London in 1782:--

"Being obliged," he says, "to

bestir myself to get back to London, as the time drew near when the Hamburgh

captain with whom I intended to return had fixed his departure, I determined

to take a place as far as Northampton on the outside. But this ride from

Leicester to Northampton I shall remember as long as I live.

"The coach drove from the

yard through a part of the house. The inside passengers got in from the

yard, but we on the outside were obliged to clamber up in the street,

because we should have had no room for our heads to pass under the gateway.

My companions on the top of the coach were a farmer, a young man very

decently dressed, and a black-a-moor. The getting up alone was at the risk

of one's life, and when I was up I was obliged to sit just at the corner of

the coach, with nothing to hold by but a sort of little handle fastened on

the side. I sat nearest the wheel, and the moment that we set off I fancied

that I saw certain death before me. All I could do was to take still tighter

hold of the handle, and to be strictly careful to preserve my balance. The

machine rolled along with prodigious rapidity over the stones through the

town, and every moment we seemed to fly into the air, so much so that it

appeared to me a complete miracle that we stuck to the coach at all. But we

were completely on the wing as often as we passed through a village or went

down a hill.

"This continual fear of death

at last became insupportable to me, and, therefore, no sooner were we

crawling up a rather steep hill, and consequently proceeding slower than

usual, then I carefully crept from the top of the coach, and was lucky

enough to get myself snugly ensconced in the basket behind. "'O,Sir, you

will be shaken to death!' said the black-a-moor; but I heeded him not,

trusting that he was exaggerating the unpleasantness of my new situation.

And truly, as long as we went on slowly up the hill it was easy and pleasant

enough; and I was just on the point of falling asleep among the surrounding

trunks and packages, having had no rest the night before, when on a sudden

the coach proceeded at a rapid rate down the hill. Then all the boxes,

iron-nailed and copper-fastened, began, as it were, to dance around me;

everything in the basket appeared to be alive, and every moment I received

such violent blows that I thought my last hour had come. The black-a-moor

had been right, I now saw clearly; but repentance was useless, and I was

obliged to suffer horrible torture for nearly an hour, which seemed to me an

eternity. At last we came to another hill, when, quite shaken to pieces,

bleeding, and sore, I ruefully crept back to the top of the coach to my

former seat. 'Ah, did I not tell you that you would be shaken to death?'

inquired the black man, when I was creeping along on my stomach. But I gave

him no reply. Indeed, I was ashamed; and I now write this as a warning to

all strangers who are inclined to ride in English stage-coaches, and take an

outside at, or, worse still, horror of horrors, a seat in the basket.

"From Harborough to

Northampton I had a most dreadful journey. It rained incessantly, and as

before we had been covered with dust, so now we were soaked with rain. My

neighbour, the young man who sat next me in the middle, every now and then

fell asleep; and when in this state he perpetually bolted and rolled against

me, with the whole weight of his body, more than once nearly pushing me from

my seat, to which I clung with the last strength of despair. My forces were

nearly giving way, when at last, happily, we reached Northampton, on

the evening of the 14th July, 1782, an ever-memorable day to me.

"On the next morning, I took

an inside place for London. We started early in the morning. The journey

from Northampton to the metropolis, however, I can scarcely call a ride, for

it was a perpetual motion, or endless jolt from one place to another, in a

close wooden box, over what appeared to be a heap of unhewn stones and

trunks of trees scattered by a hurricane. To make my happiness complete, I

had three travelling companions, all farmers, who slept so soundly that even

the hearty knocks with which they hammered their heads against each other

and against mine did not awake them. Their faces, bloated and discoloured by

ale and brandy and the knocks aforesaid, looked, as they lay before me, like

so many lumps of dead flesh.

"I looked, and certainly

felt, like a crazy fool when we arrived at London in the afternoon."*[3]

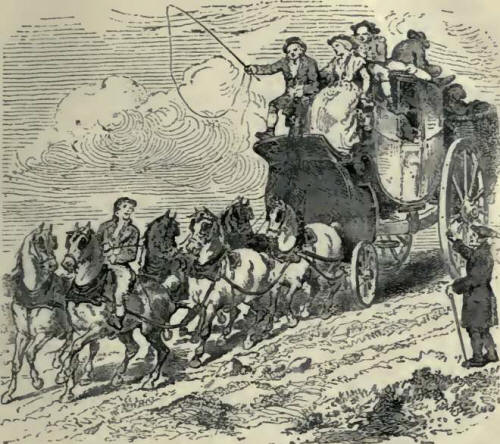

The Basket Coach, 1780.

Arthur Young, in his books,

inveighs strongly against the execrable state of the roads in all parts of

England towards the end of last century. In Essex he found the ruts "of an

incredible depth," and he almost swore at one near Tilbury. "Of all the

cursed roads, "he says, "that ever disgraced this kingdom in the very ages

of barbarism, none ever equalled that from Billericay to the King's

Head at Tilbury. It is for near twelve miles so narrow that a mouse cannot

pass by any carriage. I saw a fellow creep under his waggon to assist me to

lift, if possible, my chaise over a hedge. To add to all the infamous

circumstances which concur to plague a traveller, I must not forget the

eternally meeting with chalk waggons, themselves frequently stuck fast, till

a collection of them are in the same situation, and twenty or thirty horses

may be tacked to each to draw them out one by one!"*[4] Yet will it be

believed, the proposal to form a turnpike-road from Chelmsford to Tilbury

was resisted "by the Bruins of the country, whose horses were worried to

death with bringing chalk through those vile roads!"

Arthur Young did not find the

turnpike any better between Bury and Sudbury, in Suffolk: "I was forced to

move as slow in it," he says, "as in any unmended lane in Wales. For, ponds

of liquid dirt, and a scattering of loose flints just sufficient to lame

every horse that moves near them, with the addition of cutting vile grips

across the road under the pretence of letting the water off, but without

effect, altogether render at least twelve out of these sixteen miles as

infamous a turnpike as ever was beheld." Between Tetsworth and Oxford he

found the so-called turnpike abounding in loose stones as large as one's

head, full of holes, deep ruts, and withal so narrow that with great

difficulty he got his chaise out of the way of the Witney waggons.

"Barbarous" and "execrable" are the words which he constantly employs in

speaking of the roads; parish and turnpike, all seemed to be alike bad. From

Gloucester to Newnham, a distance of twelve miles, he found a "cursed road,"

"infamously stony," with "ruts all the way." From Newnham to Chepstow he

noted another bad feature in the roads, and that was the perpetual hills;

"for," he says, "you will form a clear idea of them if you suppose the

country to represent the roofs of houses joined, and the road to run across

them." It was at one time even matter of grave dispute whether it would not

cost as little money to make that between Leominster and Kington navigable

as to make it hard. Passing still further west, the unfortunate traveller,

who seems scarcely able to find words to express his sufferings,

continues:--

"But, my dear Sir, what am I

to say of the roads in this country! the turnpikes! as they have the

assurance to call them and the hardiness to make one pay for? From Chepstow

to the half-way house between Newport and Cardiff they continue mere rocky

lanes, full of hugeous stones as big as one's horse, and abominable holes.

The first six miles from Newport they were so detestable, and without either

direction-posts or milestones, that I could not well persuade myself I was

on the turnpike, but had mistook the road, and therefore asked every one I

met, who answered me, to my astonishment, 'Ya-as!' Whatever business carries

you into this country, avoid it, at least till they have good roads: if they

were good, travelling would be very pleasant."*[5]

At a subsequent period Arthur

Young visited the northern counties; but his account of the roads in that

quarter is not more satisfactory. Between Richmond and Darlington he found

them like to "dislocate his bones," being broken in many places into deep

holes, and almost impassable; "yet," says he, "the people will drink tea!"

--a decoction against the use of which the traveller is found constantly

declaiming. The roads in Lancashire made him almost frantic, and he gasped

for words to express his rage. Of the road between Proud Preston and Wigan

he says: "I know not in the whole range of language terms sufficiently

expressive to describe this infernal road. Let me most seriously caution all

travellers who may accidentally propose to travel this terrible country, to

avoid it as they would the devil; for a thousand to one they break their

necks or their limbs by overthrows or breakings-down.

They will here meet with

ruts, which I actually measured, four feet deep, and floating with mud only

from a wet summer. What, therefore, must it be after a winter? The only

mending it receives is tumbling in some loose stones, which serve no other

purpose than jolting a carriage in the most intolerable manner. These are

not merely opinions, but facts; for I actually passed three carts broken

down in those eighteen miles of execrable memory."*[6]

It would even appear that the

bad state of the roads in the Midland counties, about the same time, had

nearly caused the death of the heir to the throne. On the 2nd of September,

1789, the Prince of Wales left Wentworth Hall, where he had been on a visit

to Earl Fitzwilliam, and took the road for London in his carriage. When

about two miles from Newark the Prince's coach was overturned by a cart in a

narrow part of the road; it rolled down a slope, turning over three times,

and landed at the bottom, shivered to pieces. Fortunately the Prince escaped

with only a few bruises and a sprain; but the incident had no effect in

stirring up the local authorities to make any improvement in the road, which

remained in the same wretched state until a comparatively recent period.

When Palmer's new

mail-coaches were introduced, an attempt was made to diminish the jolting of

the passengers by having the carriages hung upon new patent springs, but

with very indifferent results. Mathew Boulton, the engineer, thus described

their effect upon himself in a journey he made in one of them from London

into Devonshire, in 1787:--

"I had the most disagreeable

journey I ever experienced the night after I left you, owing to the new

improved patent coach, a vehicle loaded with iron trappings and the greatest

complication of unmechanical contrivances jumbled together, that I have ever

witnessed. The coach swings sideways, with a sickly sway without any

vertical spring; the point of suspense bearing upon an arch called a spring,

though it is nothing of the sort, The severity of the jolting occasioned me

such disorder, that I was obliged to stop at Axminster and go to bed very

ill. However, I was able next day to proceed in a post-chaise. The landlady

in the London Inn, at Exeter, assured me that the passengers who arrived

every night were in general so ill that they were obliged to go supperless

to bed; and, unless they go back to the old-fashioned coach, hung a little

lower, the mail-coaches will lose all their custom."*[7]

We may briefly refer to the

several stages of improvement --if improvement it could be called--in the

most frequented highways of the kingdom, and to the action of the

legislature with reference to the extension of turnpikes. The trade and

industry of the country had been steadily improving; but the greatest

obstacle to their further progress was always felt to be the disgraceful

state of the roads. As long ago as the year 1663 an Act was passed*[8]

authorising the first toll-gates or turnpikes to be erected, at which

collectors were stationed to levy small sums from those using the road, for

the purpose of defraying the needful expenses of their maintenance. This

Act, however, only applied to a portion of the Great North Road between

London and York, and it authorised the new toll-bars to be erected at Wade's

Mill in Hertfordshire, at Caxton in Cambridgeshire, and at Stilton in

Huntingdonshire.*[9] The Act was not followed by any others for a quarter of

a century, and even after that lapse of time such Acts as were passed of a

similar character were very few and far between.

For nearly a century more,

travellers from Edinburgh to London met with no turnpikes until within about

110 miles of the metropolis. North of that point there was only a narrow

causeway fit for pack-horses, flanked with clay sloughs on either side. It

is, however, stated that the Duke of Cumberland and the Earl of Albemarle,

when on their way to Scotland in pursuit of the rebels in 1746, did contrive

to reach Durham in a coach and six; but there the roads were found so

wretched, that they were under the necessity of taking to horse, and Mr.

George Bowes, the county member, made His Royal Highness a present of his

nag to enable him to proceed on his journey. The roads west of Newcastle

were so bad, that in the previous year the royal forces under General Wade,

which left Newcastle for Carlisle to intercept the Pretender and his army,

halted the first night at Ovingham, and the second at Hexham, being able to

travel only twenty miles in two days.*[10]

The rebellion of 1745 gave a

great impulse to the construction of roads for military as well as civil

purposes. The nimble Highlanders, without baggage or waggons, had been able

to cross the border and penetrate almost to the centre of England before any

definite knowledge of their proceedings had reached the rest of the kingdom.

In the metropolis itself little information could be obtained of the

movements of the rebel army for several days after they had left Edinburgh.

Light of foot, they outstripped the cavalry and artillery of the royal army,

which were delayed at all points by impassable roads. No sooner, however,

was the rebellion put down, than Government directed its attention to the

best means of securing the permanent subordination of the Highlands, and

with this object the construction of good highways was declared to be

indispensable. The expediency of opening up the communication between the

capital and the principal towns of Scotland was also generally admitted; and

from that time, though slowly, the construction of the main high routes

between north and south made steady progress.

The extension of the turnpike

system, however, encountered violent opposition from the people, being

regarded as a grievous tax upon their freedom of movement from place to

place. Armed bodies of men assembled to destroy the turnpikes; and they

burnt down the toll-houses and blew up the posts with gunpowder. The

resistance was the greatest in Yorkshire, along the line of the Great North

Road towards Scotland, though riots also took place in Somersetshire and

Gloucestershire, and even in the immediate neighbourhood of London. One fine

May morning, at Selby, in Yorkshire, the public bellman summoned the

inhabitants to assemble with their hatchets and axes that night at midnight,

and cut down the turnpikes erected by Act of Parliament; nor were they slow

to act upon his summons. Soldiers were then sent into the district to

protect the toll-bars and the toll-takers; but this was a difficult matter,

for the toll-gates were numerous, and wherever a "pike" was left unprotected

at night, it was found destroyed in the morning. The Yeadon and Otley mobs,

near Leeds, were especially violent. On the 18th of June, 1753, they made

quite a raid upon the turnpikes, burning or destroying about a dozen in one

week. A score of the rioters were apprehended, and while on their way to

York Castle a rescue was attempted, when the soldiers were under the

necessity of firing, and many persons were killed and wounded. The

prejudices entertained against the turnpikes were so strong, that in some

places the country people would not even use the improved roads after they

were made.*[11] For instance, the driver of the Marlborough coach

obstinately refused to use the New Bath road, but stuck to the old waggon-track,

called "Ramsbury." He was an old man, he said: his grandfather and father

had driven the aforesaid way before him, and he would continue in the old

track till death.*[12] Petitions were also presented to Parliament against

the extension of turnpikes; but the opposition represented by the

petitioners was of a much less honest character than that of the misguided

and prejudiced country folks, who burnt down the toll-houses. It was

principally got up by the agriculturists in the neighbourhood of the

metropolis, who, having secured the advantages which the turnpike-roads

first constructed had conferred upon them, desired to retain a monopoly of

the improved means of communication. They alleged that if turnpike-roads

were extended into the remoter counties, the greater cheapness of labour

there would enable the distant farmers to sell their grass and corn cheaper

in the London market than themselves, and that thus they would be

ruined.*[13]

This opposition, however, did

not prevent the progress of turnpike and highway legislation; and we find

that, from l760 to l774, no fewer than four hundred and fifty-two Acts were

passed for making and repairing highways. Nevertheless the roads of the

kingdom long continued in a very unsatisfactory state, chiefly arising from

the extremely imperfect manner in which they were made.

Road-making as a profession

was as yet unknown. Deviations were made in the old roads to make them more

easy and straight; but the deep ruts were merely filled up with any

materials that lay nearest at hand, and stones taken from the quarry,

instead of being broken and laid on carefully to a proper depth, were

tumbled down and roughly spread, the country road-maker trusting to the

operation of cart-wheels and waggons to crush them into a proper shape. Men

of eminence as engineers--and there were very few such at the time--

considered road-making beneath their consideration; and it was even thought

singular that, in 1768, the distinguished Smeaton should have condescended

to make a road across the valley of the Trent, between Markham and Newark.

The making of the new roads

was thus left to such persons as might choose to take up the trade, special

skill not being thought at all necessary on the part of a road-maker. It is

only in this way that we can account for the remarkable fact, that the first

extensive maker of roads who pursued it as a business, was not an engineer,

nor even a mechanic, but a Blind Man, bred to no trade, and possessing no

experience whatever in the arts of surveying or bridge-building, yet a man

possessed of extraordinary natural gifts, and unquestionably most successful

as a road-maker. We allude to John Metcalf, commonly known as "Blind Jack of

Knaresborough," to whose biography, as the constructor of nearly two hundred

miles of capital roads--as, indeed, the first great English road-maker--we

propose to devote the next chapter.

Footnotes for Chapter V.

*[1] Lady Luxborough, in a

letter to Shenstone the poet, in 1749, says,--"A Birmingham coach is newly

established to our great emolument. Would it not be a good scheme (this

dirty weather, when riding is no more a pleasure) for you to come some

Monday in the said stage-coach from Birmingham to breakfast at Barrells,

(for they always breakfast at Henley); and on the Saturday following it

would convey you back to Birmingham, unless you would stay longer, which

would be better still, and equally easy; for the stage goes every week the

same road. It breakfasts at Henley, and lies at Chipping Horton; goes early

next day to Oxford, stays there all day and night, and gets on the third day

to London; which from Birmingham at this season is pretty well, considering

how long they are at Oxford; and it is much more agreeable as to the country

than the Warwick way was."

*[2] We may incidentally

mention three other journeys south by future Lords Chancellors. Mansfield

rode up from Scotland to London when a boy, taking two months to make the

journey on his pony. Wedderburn's journey by coach from Edinburgh to London,

in 1757, occupied him six days. "When I first reached London," said the late

Lord Campbell, "I performed the same journey in three nights and two days,

Mr. Palmer's mail-coaches being then established; but this swift travelling

was considered dangerous as well as wonderful, and I was gravely advised to

stay a day at York, as several passengers who had gone through without

stopping had died of apoplexy from the rapidity of the motion!"

*[3] C. H. Moritz: 'Reise

eines Deutschen in England im Jahre 1782.' Berlin, 1783.

*[4] Arthur Young's 'Six

Weeks' Tour in the Southern Counties of England and Wales,' 2nd ed., 1769,

pp. 88-9.

*[5] 'Six Weeks Tour' in the

Southern Counties of England and Wales,' pp. 153-5. The roads all over South

Wales were equally bad down to the beginning of the present century. At

Halfway, near Trecastle, in Breconshire, South Wales, a small obelisk is

still to be seen, which was erected to commemorate the turn over and

destruction of the mail coach over a steep of 130 feet; the driver and

passengers escaping unhurt.

*[6] 'A Six Months' Tour

through the North of England,' vol. iv., p. 431.

*[7] Letter to Wyatt, October

5th, 1787, MS.

*[8] Act 15 Car. II., c. 1.

*[9] The preamble of the Act

recites that "The ancient highway and post-road leading from London to York,

and so into Scotland, and likewise from London into Lincolnshire, lieth for

many miles in the counties of Hertford, Cambridge, and Huntingdon, in many

of which places the road, by reason of the great and many loads which are

weekly drawn in waggons through the said places, as well as by reason of the

great trade of barley and malt that cometh to Ware, and so is conveyed by

water to the city of London, as well as other carriages, both from the north

parts as also from the city of Norwich, St. Edmondsbury, and the town of

Cambridge, to London, is very ruinous, and become almost impassable,

insomuch that it is become very dangerous to all his Majesty's liege people

that pass that way," &c.

*[10] Down to the year 1756,

Newcastle and Carlisle were only connected by a bridle way. In that year,

Marshal Wade employed his army to construct a road by way of Harlaw and

Cholterford, following for thirty miles the line of the old Roman Wall, the

materials of which he used to construct his "agger" and culverts. This was

long after known as "the military road."

*[11] The Blandford waggoner

said, "Roads had but one object--for waggon-driving. He required but

four-foot width in a lane, and all the rest might go to the devil." He

added, "The gentry ought to stay at home, and be d----d, and not run

gossiping up and down the country."--Roberts's 'Social History of the

Southern Counties.'

*[12] 'Gentleman's Magazine'

for December, 1752.

*[13] Adam Smith's 'Wealth of

Nations,' book i., chap. xi., part i. |