|

While the road communications

of the country remained thus imperfect, the people of one part of England

knew next to nothing of the other. When a shower of rain had the effect of

rendering the highways impassable, even horsemen were cautious in venturing

far from home. But only a very limited number of persons could then afford

to travel on horseback. The labouring people journeyed on foot, while the

middle class used the waggon or the coach. But the amount of intercourse

between the people of different districts --then exceedingly limited at all

times--was, in a country so wet as England, necessarily suspended for all

classes during the greater part of the year.

The imperfect communication

existing between districts had the effect of perpetuating numerous local

dialects, local prejudices, and local customs, which survive to a certain

extent to this day; though they are rapidly disappearing, to the regret of

many, under the influence of improved facilities for travelling. Every

village had its witches, sometimes of different sorts, and there was

scarcely an old house but had its white lady or moaning old man with a long

beard. There were ghosts in the fens which walked on stilts, while the

sprites of the hill country rode on flashes of fire. But the village witches

and local ghosts have long since disappeared, excepting perhaps in a few of

the less penetrable districts, where they may still survive. It is curious

to find that down even to the beginning of the seventeenth century, the

inhabitants of the southern districts of the island regarded those of the

north as a kind of ogres. Lancashire was supposed to be almost

impenetrable-- as indeed it was to a considerable extent,--and inhabited by

a half-savage race. Camden vaguely described it, previous to his visit in

1607, as that part of the country " lying beyond the mountains towards the

Western Ocean." He acknowledged that he approached the Lancashire people

"with a kind of dread," but determined at length "to run the hazard of the

attempt," trusting in the Divine assistance. Camden was exposed to still

greater risks in his survey of Cumberland. When he went into that county for

the purpose of exploring the remains of antiquity it contained for the

purposes of his great work, he travelled along the line of the Roman Wall as

far as Thirlwall castle, near Haltwhistle; but there the limits of

civilization and security ended; for such was the wildness of the country

and of its lawless inhabitants beyond, that he was obliged to desist from

his pilgrimage, and leave the most important and interesting objects of his

journey unexplored.

About a century later, in

1700, the Rev. Mr. Brome, rector of Cheriton in Kent, entered upon a series

of travels in England as if it had been a newly-discovered country. He set

out in spring so soon as the roads had become passable. His friends convoyed

him on the first stage of his journey, and left him, commending him to the

Divine protection. He was, however, careful to employ guides to conduct him

from one place to another, and in the course of his three years' travels he

saw many new and wonderful things. He was under the necessity of suspending

his travels when the winter or wet weather set in, and to lay up, like an

arctic voyager, for several months, until the spring came round again. Mr.

Brome passed through Northumberland into Scotland, then down the

western side of the island towards Devonshire, where he found the farmers

gathering in their corn on horse-back, the roads being so narrow that it was

impossible for them to use waggons. He desired to travel into Cornwall, the

boundaries of which he reached, but was prevented proceeding farther by the

rains, and accordingly he made the best of his way home.*[1] The vicar of

Cheriton was considered a wonderful man in his day,-- almost as as venturous

as we should now regard a traveller in Arabia. Twenty miles of slough, or an

unbridged river between two parishes, were greater impediments to

intercourse than the Atlantic Ocean now is between England and America.

Considerable towns situated in the same county, were then more widely

separated, for practical purposes, than London and Glasgow are at the

present day. There were many districts which travellers never visited, and

where the appearance of a stranger produced as great an excitement as the

arrival of a white man in an African village.*[2]

The author of 'Adam Bede' has

given us a poet's picture of the leisure of last century, which has "gone

where the spinning-wheels are gone, and the pack-horses, and the slow

waggons, and the pedlars who brought bargains to the door on sunny

afternoons. "Old Leisure" lived chiefly in the country, among pleasant seats

and homesteads, and was fond of sauntering by the fruit-tree walls, and

scenting the apricots when they were warmed by the morning sunshine, or

sheltering himself under the orchard boughs at noon, when the summer pears

were falling." But this picture has also its obverse side. Whole generations

then lived a monotonous, ignorant, prejudiced, and humdrum life. They had no

enterprize, no energy, little industry, and were content to die where they

were born. The seclusion in which they were compelled to live, produced a

picturesqueness of manners which is pleasant to look back upon, now that it

is a thing of the past; but it was also accompanied with a degree of

grossness and brutality much less pleasant to regard, and of which the

occasional popular amusements of bull-running, cock-fighting, cock-throwing,

the saturnalia of Plough-Monday, and such like, were the fitting exponents.

People then knew little

except of their own narrow district. The world beyond was as good as closed

against them. Almost the only intelligence of general affairs which reached

them was communicated by pedlars and packmen, who were accustomed to retail

to their customers the news of the day with their wares; or, at most, a

newsletter from London, after it had been read nearly to pieces at the great

house of the district, would find its way to the village, and its driblets

of information would thus become diffused among the little community.

Matters of public interest were long in becoming known in the remoter

districts of the country. Macaulay relates that the death of Queen Elizabeth

was not heard of in some parts of Devon until the courtiers of her successor

had ceased to wear mourning for her. The news of Cromwell's being made

Protector only reached Bridgewater nineteen days after the event, when the

bells were set a-ringing; and the churches in the Orkneys continued to put

up the usual prayers for James II. three months after he had taken up his

abode at St. Germains. There were then no shops in the smaller towns or

villages, and comparatively few in the larger; and these were badly

furnished with articles for general use. The country people were irregularly

supplied by hawkers, who sometimes bore their whole stook upon their back,

or occasionally on that of their pack-horses. Pots, pans, and household

utensils were sold from door to door. Until a comparatively recent period,

the whole of the pottery-ware manufactured in Staffordshire was hawked about

and disposed of in this way. The pedlars carried frames resembling

camp-stools, on which they were accustomed to display their wares when the

opportunity occurred for showing them to advantage. The articles which they

sold were chiefly of a fanciful kind--ribbons, laces, and female finery; the

housewives' great reliance for the supply of general clothing in those days

being on domestic industry.

Every autumn, the mistress of

the household was accustomed to lay in a store of articles sufficient to

serve for the entire winter. It was like laying in a stock of provisions and

clothing for a siege during the time that the roads were closed. The greater

part of the meat required for winter's use was killed and salted down at

Martinmas, while stockfish and baconed herrings were provided for Lent.

Scatcherd says that in his district the clothiers united in groups of three

or four, and at the Leeds winter fair they would purchase an ox, which,

having divided, they salted and hung the pieces for their winter's food.*[3]

There was also the winter's stock of firewood to be provided, and the rushes

with which to strew the floors--carpets being a comparatively modern

invention; besides, there was the store of wheat and barley for bread, the

malt for ale, the honey for sweetening (then used for sugar), the salt, the

spiceries, and the savoury herbs so much employed in the ancient cookery.

When the stores were laid in, the housewife was in a position to bid

defiance to bad roads for six months to come. This was the case of the

well-to-do; but the poorer classes, who could not lay in a store for winter,

were often very badly off both for food and firing, and in many hard seasons

they literally starved. But charity was active in those days, and many a

poor man's store was eked out by his wealthier neighbour.

When the household supply was

thus laid in, the mistress, with her daughters and servants, sat down to

their distaffs and spinning-wheels; for the manufacture of the family

clothing was usually the work of the winter months. The fabrics then worn

were almost entirely of wool, silk and cotton being scarcely known. The

wool, when not grown on the farm, was purchased in a raw state, and was

carded, spun, dyed, and in many cases woven at home: so also with the linen

clothing, which, until quite a recent date, was entirely the produce of

female fingers and household spinning-wheels. This kind of work occupied the

winter months, occasionally alternated with knitting, embroidery, and

tapestry work. Many of our country houses continue to bear witness to the

steady industry of the ladies of even the highest ranks in those times, in

the fine tapestry hangings with which the walls of many of the older rooms

in such mansions are covered.

Among the humbler classes,

the same winter's work went on. The women sat round log fires knitting,

plaiting, and spinning by fire-light, even in the daytime. Glass had not yet

come into general use, and the openings in the wall which in summer-time

served for windows, had necessarily to be shut close with boards to keep out

the cold, though at the same time they shut out the light. The chimney,

usually of lath and plaster, ending overhead in a cone and funnel for the

smoke, was so roomy in old cottages as to accommodate almost the whole

family sitting around the fire of logs piled in the reredosse in the middle,

and there they carried on their winter's work.

Such was the domestic

occupation of women in the rural districts in olden times; and it may

perhaps be questioned whether the revolution in our social system, which has

taken out of their hands so many branches of household manufacture and

useful domestic employment, be an altogether unmixed blessing.

Winter at an end, and the

roads once more available for travelling, the Fair of the locality was

looked forward to with interest. Fairs were among the most important

institutions of past times, and were rendered necessary by the imperfect

road communications. The right of holding them was regarded as a valuable

privilege, conceded by the sovereign to the lords of the manors, who adopted

all manner of devices to draw crowds to their markets. They were usually

held at the entrances to valleys closed against locomotion during winter, or

in the middle of rich grazing districts, or, more frequently, in the

neighbourhood of famous cathedrals or churches frequented by flocks of

pilgrims. The devotion of the people being turned to account, many of the

fairs were held on Sundays in the churchyards; and almost in every parish a

market was instituted on the day on which the parishioners were called

together to do honour to their patron saint.

The local fair, which was

usually held at the beginning or end of winter, often at both times, became

the great festival as well as market of the district; and the business as

well as the gaiety of the neighbourhood usually centred on such occasions.

High courts were held by the Bishop or Lord of the Manor, to accommodate

which special buildings were erected, used only at fair time. Among the

fairs of the first class in England were Winchester, St. Botolph's Town

(Boston), and St. Ives. We find the great London merchants travelling

thither in caravans, bearing with them all manner of goods, and bringing

back the wool purchased by them in exchange.

Winchester Great Fair

attracted merchants from all parts of Europe. It was held on the hill of St.

Giles, and was divided into streets of booths, named after the merchants of

the different countries who exposed their wares in them. "The passes through

the great woody districts, which English merchants coming from London and

the West would be compelled to traverse, were on this occasion carefully

guarded by mounted 'serjeants-at-arms,' since the wealth which was being

conveyed to St. Giles's-hill attracted bands of outlaws from all parts of

the country."*[4] Weyhill Fair, near Andover, was another of the great fairs

in the same district, which was to the West country agriculturists and

clothiers what Winchester St. Giles's Fair was to the general merchants.

The principal fair in the

northern districts was that of St. Botolph's Town (Boston), which was

resorted to by people from great distances to buy and sell commodities of

various kinds. Thus we find, from the 'Compotus' of Bolton Priory,*[5] that

the monks of that house sent their wool to St. Botolph's Fair to be sold,

though it was a good hundred miles distant; buying in return their winter

supply of groceries, spiceries, and other necessary articles. That fair,

too, was often beset by robbers, and on one occasion a strong party of them,

under the disguise of monks, attacked and robbed certain booths, setting

fire to the rest; and such was the amount of destroyed wealth, that it is

said the veins of molten gold and silver ran along the streets.

The concourse of persons

attending these fairs was immense. The nobility and gentry, the heads of the

religions houses, the yeomanry and the commons, resorted to them to buy and

sell all manner of agricultural produce. The farmers there sold their wool

and cattle, and hired their servants; while their wives disposed of the

surplus produce of their winter's industry, and bought their cutlery,

bijouterie, and more tasteful articles of apparel. There were caterers there

for all customers; and stuffs and wares were offered for sale from all

countries. And in the wake of this business part of the fair there

invariably followed a crowd of ministers to the popular tastes-- quack

doctors and merry andrews, jugglers and minstrels, singlestick players,

grinners through horse-collars, and sportmakers of every kind.

Smaller fairs were held in

most districts for similar purposes of exchange. At these the staples of the

locality were sold and servants usually hired. Many were for special

purposes--cattle fairs, leather fairs, cloth fairs, bonnet fairs, fruit

fairs. Scatcherd says that less than a century ago a large fair was held

between Huddersfield and Leeds, in a field still called Fairstead, near

Birstal, which used to be a great mart for fruit, onions, and such like; and

that the clothiers resorted thither from all the country round to purchase

the articles, which were stowed away in barns, and sold at booths by

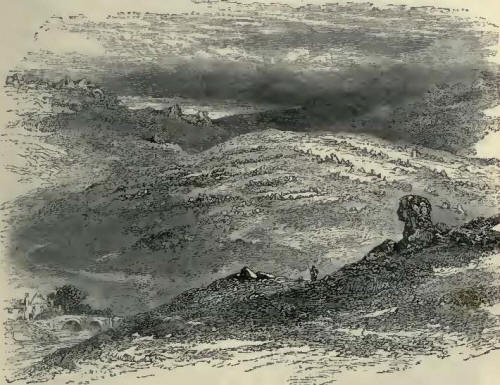

lamplight in the morning.*[6] Even Dartmoor had its fair, on the site of an

ancient British village or temple near Merivale Bridge, testifying to its

great antiquity; for it is surprising how an ancient fair lingers about the

place on which it has been accustomed to be held, long after the necessity

for it has ceased. The site of this old fair at Merivale Bridge is the more

curious, as in its immediate neighbourhood, on the road between Two Bridges

and Tavistock, is found the singular-looking granite rock, bearing so

remarkable a resemblance to the Egyptian sphynx, in a mutilated state. It is

of similarly colossal proportions, and stands in a district almost as lonely

as that in which the Egyptian sphynx looks forth over the sands of the

Memphean Desert.*[7]

Site of an ancient British village and fair on Dartmoor.

The last occasion on which

the fair was held in this secluded spot was in the year 1625, when the

plague raged at Tavistock; and there is a part of the ground, situated

amidst a line of pillars marking a stone avenue--a characteristic feature of

the ancient aboriginal worship--which is to this day pointed out and called

by the name of the "Potatoe market."

But the glory of the great

fairs has long since departed. They declined with the extension of

turnpikes, and railroads gave them their death-blow. Shops now exist in

every little town and village, drawing their supplies regularly by road and

canal from the most distant parts. St. Bartholomew, the great fair of

London,*[8] and Donnybrook, the great fair of Dublin, have been suppressed

as nuisances; and nearly all that remains of the dead but long potent

institution of the Fair, is the occasional exhibition at periodic times in

country places, of pig-faced ladies, dwarfs, giants, double-bodied calves,

and such-like wonders, amidst a blatant clangour of drums, gongs, and

cymbals. Like the sign of the Pack-Horse over the village inn door, the

modern village fair, of which the principal article of merchandise is

gingerbread-nuts, is but the vestige of a state of things that has long

since passed away.

There were, however, remote

and almost impenetrable districts which long resisted modern inroads. Of

such was Dartmoor, which we have already more than once referred to. The

difficulties of road-engineering in that quarter, as well as the sterility

of a large proportion of the moor, had the effect of preventing its becoming

opened up to modern traffic; and it is accordingly curious to find how much

of its old manners, customs, traditions, and language has been preserved. It

looks like a piece of England of the Middle Ages, left behind on the march.

Witches still hold their sway on Dartmoor, where there exist no less than

three distinct kinds-- white, black, and grey,*[9]--and there are still

professors of witchcraft, male as well as female, in most of the villages.

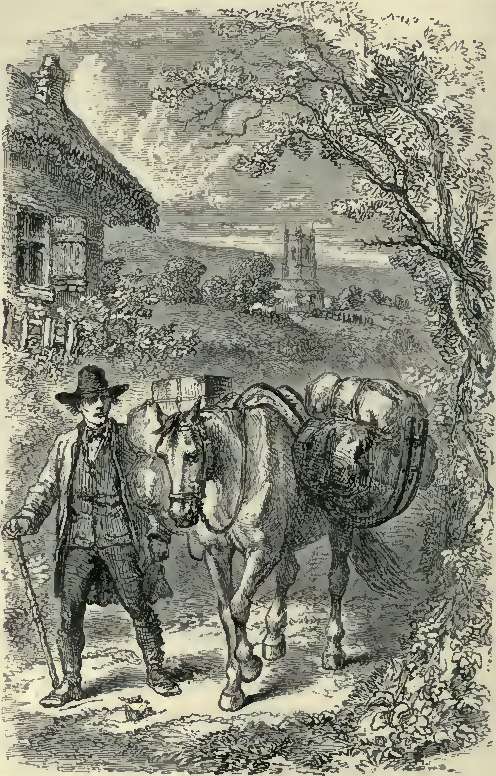

As might be expected, the

pack-horses held their ground in Dartmoor the longest, and in some parts of

North Devon they are not yet extinct. When our artist was in the

neighbourhood, sketching the ancient bridge on the moor and the site of the

old fair, a farmer said to him, "I well remember the train of pack-horses

and the effect of their jingling bells on the silence of Dartmoor. My

grandfather, a respectable farmer in the north of Devon, was the first to

use a 'butt' (a square box without wheels, dragged by a horse) to carry

manure to field; he was also the first man in the district to use an

umbrella, which on Sundays he hung in the church-porch, an object of

curiosity to the villagers." We are also informed by a gentleman who resided

for some time at South Brent', on the borders of the Moor, that the

introduction of the first cart in that district is remembered by many now

living, the bridges having been shortly afterwards widened to accommodate

the wheeled vehicles.

The primitive features of

this secluded district are perhaps best represented by the interesting

little town of Chagford, situated in the valley of the North Teign, an

ancient stannary and market town backed by a wide stretch of moor. The

houses of the place are built of moor stone--grey, venerable-looking, and

substantial--some with projecting porch and parvise room over, and

granite-mullioned windows; the ancient church, built of granite, with a

stout old steeple of the same material, its embattled porch and

granite-groined vault springing from low columns with Norman-looking

capitals, forming the sturdy centre of this ancient town clump.

A post-chaise is still a

phenomenon in Chagford, the roads and lanes leading to it being so steep and

rugged as to be ill adapted for springed vehicles of any sort. The upland

road or track to Tavistock scales an almost precipitous hill, and though

well enough adapted for the pack-horse of the last century, it is quite

unfitted for the cart and waggon traffic of this. Hence the horse with

panniers maintains its ground in the Chagford district; and the

double-horse, furnished with a pillion for the lady riding behind, is still

to be met with in the country roads.

Among the patriarchs of the

hills, the straight-breasted blue coat may yet be seen, with the shoe

fastened with buckle and strap as in the days when George III. was king; and

old women are still found retaining the cloak and hood of their youth. Old

agricultural implements continue in use. The slide or sledge is seen in the

fields; the flail, with its monotonous strokes, resounds from the

barn-floors; the corn is sifted by the windstow--the wind merely blowing

away the chaff from the grain when shaken out of sieves by the motion of the

hand on some elevated spot; the old wooden plough is still at work, and the

goad is still used to urge the yoke of oxen in dragging it along.

The Devonshire Crooks

"In such a place as Chagford,"

says Mr. Rowe, "the cooper or rough carpenter will still find a demand for

the pack-saddle, with its accompanying furniture of crooks, crubs, or

dung-pots. Before the general introduction of carts, these rough and ready

contrivances were found of great utility in the various operations of

husbandry, and still prove exceedingly convenient in situations almost, or

altogether, inaccessible to wheel-carriages. The long crooks are used for

the carriage of corn in sheaf from the harvest-field to the mowstead or

barn, for the removal of furze, browse, faggot-wood, and other light

materials. The writer of one of the happiest effusions of the local

muse,*[10] with fidelity to nature equal to Cowper or Crabbe, has introduced

the figure of a Devonshire pack-horse bending under the 'swagging load' of

the high-piled crooks as an emblem of care toiling along the narrow and

rugged path of life. The force and point of the imagery must be lost to

those who have never seen (and, as in an instance which came under my own

knowledge, never heard of) this unique specimen of provincial agricultural

machinery. The crooks are formed of two poles,*[11] about ten feet long,

bent, when green, into the required curve, and when dried in that shape are

connected by horizontal bars. A pair of crooks, thus completed, is slung

over the pack-saddle--one 'swinging on each side to make the balance true.'

The short crooks, or crubs, are slung in a similar manner. These are of

stouter fabric, and angular shape, and are used for carrying logs of wood

and other heavy materials. The dung-pots, as the name implies, were also

much in use in past times, for the removal of dung and other manure from the

farmyard to the fallow or plough lands. The slide, or sledge, may also still

occasionally be seen in the hay or corn fields, sometimes without, and in

other cases mounted on low wheels, rudely but substantially formed of thick

plank, such as might have brought the ancient Roman's harvest load to the

barn some twenty centuries ago."

Mrs. Bray says the crooks are

called by the country people "Devil's tooth-picks." A correspondent informs

us that the queer old crook-packs represented in our illustration are still

in use in North Devon. He adds: "The pack-horses were so accustomed to their

position when travelling in line (going in double file) and so jealous of

their respective places, that if one got wrong and took another's place, the

animal interfered with would strike at the offender with his crooks."

Footnotes for Chapter III.

*[1] 'Three Years' Travels in

England, Scotland, and Wales.' By James Brome, M.A., Rector of Cheriton,

Kent. London, 1726.

*[2] The treatment the

stranger received was often very rude. When William Hutton, of Birmingham,

accompanied by another gentleman, went to view the field of Bosworth, in

1770, "the inhabitants," he says, "set their dogs at us in the street,

merely because we were strangers. Human figures not their own are seldom

seen in these inhospitable regions. Surrounded with impassable roads, no

intercourse with man to humanise the mind. nor commerce to smooth their

rugged manners, they continue the boors of Nature." In certain villages in

Lancashire and Yorkshire, not very remote from large towns, the appearance

of a stranger, down to a comparatively recent period, excited a similar

commotion amongst the villagers, and the word would pass from door to door,

"Dost knaw'im?" "Naya." "Is 'e straunger?" "Ey, for sewer." "Then paus' 'im--

'Eave a duck [stone] at 'im-- Fettle 'im!" And the "straunger" would

straightway find the "ducks" flying about his head, and be glad to make his

escape from the village with his life.

*[3] Scatcherd, 'History of

Morley.'

*[4] Murray's ' Handbook of

Surrey, Hants, and Isle of Wight,' 168.

*[5] Whitaker's 'History of

Craven.'

*[6] Scatcherd's 'History of

Morley,' 226.

*[7] Vixen Tor is the name of

this singular-looking rock. But it is proper to add, that its appearance is

probably accidental, the head of the Sphynx being produced by the three

angular blocks of rock seen in profile. Mr. Borlase, however, in his '

Antiquities of Cornwall,' expresses the opinion that the rock-basins on the

summit of the rock were used by the Druids for purposes connected with their

religious ceremonies.

*[8] The provisioning of

London, now grown so populous, would be almost impossible but for the

perfect system of roads now converging on it from all parts. In early times,

London, like country places, had to lay in its stock of salt-provisions

against winter, drawing its supplies of vegetables from the country within

easy reach of the capital. Hence the London market-gardeners petitioned

against the extension of tumpike-roads about a century ago, as they

afterwards petitioned against the extension of railways, fearing lest their

trade should be destroyed by the competition of country-grown cabbages. But

the extension of the roads had become a matter of absolute necessity, in

order to feed the huge and ever-increasing mouth of the Great Metropolis,

the population of which has grown in about two centuries from four hundred

thousand to three millions. This enormous population has, perhaps, never at

any time more than a fortnight's supply of food in stock, and most families

not more than a few days; yet no one ever entertains the slightest

apprehension of a failure in the supply, or even of a variation in the price

from day to day in consequence of any possible shortcoming. That this should

be so, would be one of the most surprising things in the history of modern

London, but that it is sufficiently accounted for by the magnificent system

of roads, canals, and railways, which connect it with the remotest corners

of the kingdom. Modern London is mainly fed by steam. The Express

Meat-Train, which runs nightly from Aberdeen to London, drawn by two engines

and makes the journey in twenty-four hours, is but a single illustration of

the rapid and certain method by which modem London is fed. The north

Highlands of Scotland have thus, by means of railways, become

grazing-grounds for the metropolis. Express fish trains from Dunbar and

Eyemouth (Smeaton's harbours), augmented by fish-trucks from Cullercoats and

Tynemouth on the Northumberland coast, and from Redcar, Whitby, and

Scarborough on the Yorkshire coast, also arrive in London every morning. And

what with steam-vessels bearing cattle, and meat and fish arriving by sea,

and canal-boats laden with potatoes from inland, and railway-vans laden with

butter and milk drawn from a wide circuit of country, and road-vans piled

high with vegetables within easy drive of Covent Garden, the Great Mouth is

thus from day to day regularly, satisfactorily, and expeditiously filled.

*[9] The white witches are

kindly disposed, the black cast the "evil eye," and the grey are consulted

for the discovery of theft, &c.

*[10] See 'The Devonshire

Lane', above quoted

*[11] Willow saplings,

crooked and dried in the required form. |