|

THERE are two factors

which must be considered when the time comes to fit the cabin to the

situation. First, the fixed meteorological conditions, such as sunshine,

the prevailing summer breezes, etc., and next the outlook. These may

present conflicting claims. It is hard to generalize about unknown

sites, but a few essentials must be kept in mind for any situation.

Give the prospect first

place, for your wood home is to be regarded rather as a shelter into

which you have brought all the great out-doors possible, and to which

you may turn when the real out-doors shall make you seek it. Sunlight

you must have, for part of the day at least, especially during the early

morning hours. It is universally conceded to be more hygienic the more

the camp is exposed to the sunlight. For this reason, when the time for

clearing away the trees comes, thin them out around the camp more than

you have ever intended to do with a wood home. Thus the sunlight and

aromatic odors of the forest will rush in upon you, and the cabin will

take on an added charm.

Of course, you will not

build in a marshy or low situation. In the woods it is well to look for

indications of what occurs during or after a protracted period of rain.

Otherwise you may build in a spot which seems ideal, only to find that

your cabin is directly in the path of all the rushing surface water of

your vicinity. Therefore, seek an elevation so as to have good drainage.

Naturally one of the

first considerations you will give to your future site will be that of

the water supply and its purity, for much depends upon this.

If a spring be at hand it

will more than repay considerable care on your part. Bank up the earth

about it for a considerable distance to discourage surface water from

working its way in, then dig down a short distance and wall the spring

up with either stones or brick laid in Portland cement, the whole

smoothed off as neatly as possible to facilitate the cleansing which

must be done from time to time. A covering of some sort that will permit

active ventilation should now be erected over the spring to keep out

falling leaves and refuse. Care should be taken to keep all rubbish,

etc., as far from the spring as possible. Slop water of any kind should

never be thrown near the spring. To keep the earth clean in the vicinity

of the water supply is of the greatest importance and requires constant

watchfulness.

Should it chance that the

spring is upon an elevation, it would be a simple matter to pipe it into

the house, thus securing running water. The pipes may be laid on the

surface of the ground and disconnected in the winter after having the

water drained from them. It is not advisable to have drinking water

stand. If it is necessary, however, to store it for a time, an

earthenware crock or vessel is the proper thing. This should be well

washed and scalded at frequent intervals.

Ponds and streams are not

desirable sources of supply for drinking water because of the vast

surface drainage they receive.

Should you be fortunate

enough to have a small brook running near, by all means endeavor to dam

it, and thus secure a miniature pond and waterfall. The banks of the

pond may be made glorious with suitable plants, cardinal flowers, etc.,

and such an opportunity to build a curving rustic bridge is not to be

neglected. Cover up your traces, however.

Now, an important feature

of your wood home is proper sewage, and this demands attention. The

outhouse should be built to accommodate, under the seat, a movable box

lined with zinc or, better still, a galvanized iron pail, not too large,

and made to fit close under the seat. This should be supplied with a

layer of dry earth or wood ashes and the contents removed at frequent

intervals, to be buried and covered with earth. Soil near the surface

(if not too sandy) is in a large degree able to destroy organic matter;

the waste should not, therefore, be buried deeply. One foot is quite

sufficient.

Garbage is best disposed

of by burning. If this is not possible, dig a hole for it and cover it

over with earth. A sprinkling of chloride of lime is recommended before

covering. This will lessen materially the number of house-flies.

Look carefully after the

overhanging branches of trees near the camp and trim the dead ones off

to forestall any accidents to your roof or window glass.

Whenever a branch is

removed, whether a dead or a live one, it must be cut off close to and

even with the trunk, no matter how large the wound. The new wood and

bark will then in time cover the denuded space. If the branch is not cut

off close to the tree the projecting stub soon decays, the bark falls

off and the rot penetrates quickly to the heart of the tree.

In removing a large

branch, enough of the outer portion should be first sawed off to prevent

its weight from splitting the wood downward. All wounds should be

covered with white lead, coal tar, or creosote. No pruning should be

done, however, until the fall, if possible.

Occasionally it may be

necessary to remove a rock, and while this looks like a great task, if

the rock is large, yet after all the matter is comparatively simple.

Slaty rocks may be easily separated by starting a wedge in the different

strata and with a few sharp blows an entire slab will loosen and may be

disposed of.

Granite, etc., is a

little more difficult, though if tools are lacking a hot fire may be

built on and around the bowlder. This should be kept going for some

time. Then cold water thrown on the rock will cause it to split and

crack as though a charge of powder had been under it. A good blasting

powder is perhaps the quickest and most efficient, and if you should

decide to use this, get the brand known as Hercules, made by the du Pont

Company, who will send you simple directions for its use.

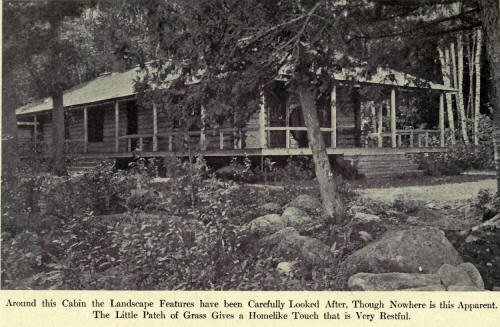

This brings us to the

question of what is best to be done with the landscape features about

us. With some this means a general clearing up. All the rocks, bushes,

etc., must go. But there are times when the big boulders, which are

never easy to remove, may be made most attractive. Virginia creeper or

honeysuckle will twine lovingly about it if you give them a start, and

doubtless the moss and lichens have already done their work in the

beautifying. At its base the woody plants and ferns may be gathered.

Ferns may be used to advantage in many places, and they will repay the

care you take in setting them in the situations where you desire their

mossy soft green effect. They are best transplanted in the spring or

early summer. Some of the stronger growing may be moved at almost any

time during the growing season. Care should be taken to secure a

good-sized ball of earth with the roots, and then in planting they

should not be buried too deeply, and have the sod pressed firmly about

the roots.

An occasional note of

color may be had in the sunnier situations with either the creeping or

dwarf nasturtiums.

Whatever is done,

however, with plants, should in no sense suggest the city or country

gardens.

Roadways into the camp

are oftentimes desirable, but the building of a road through the forest

is a question of men and teams. Lumbermen estimate that the cost is

about one dollar a rod.

You will be surprised,

however, how much one or two men can accomplish in a day in the matter

of building paths or trails. Prospect over the ground carefully and

decide upon the smoothest and most practical route, then with your ax

blaze the trail. Now commence in the underbrush and small stuff. Some

will have to be cut. Cedar, etc., may be uprooted and dragged out with a

little effort. Throw the rocks and pieces of stumps into the holes;

knock the tops off the hummocks into the low places. Whole sheets of

earth and moss may be stripped from the rocks and used to fill in and

cover with. Thus, with comparatively little effort, a smooth trail

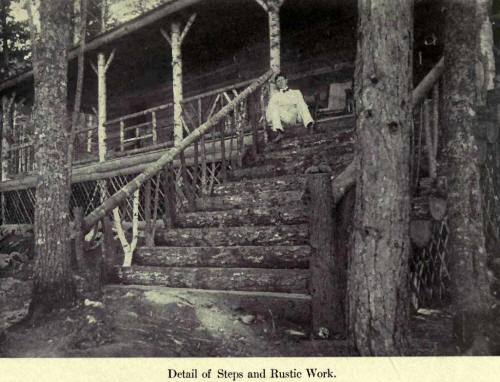

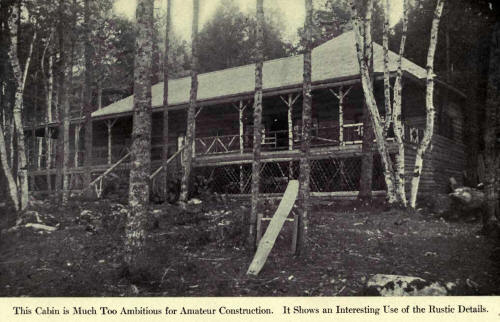

through the woods is made. Should the trail take you over any sudden

depression, build a rustic bridge. Two or three logs laid side by side

will make it, and handrails may as easily be put in place. A little

rustic bridge or flight of stone steps at some unlooked-for point gives

a note of pleasant surprise that is well worth while.

Take extraordinary care

that no fires get started. In the forest it is a common thing for a fire

to work its way underground without a sign, until suddenly it will burst

into a waving flame, terrible and inexorable. Even when you have

apparently stamped out the last spark and flooded the ground with water

the fire may reappear in the next twenty-four hours, burning as

determinedly as before.

If you have brush to

burn, pile it upon the shore as far from the trees as possible, then

wait for a favorable day. This will be immediately after a rain, either

in a calm or with a slight breeze blowing toward the lake.

While there are

innumerable advantages in living in the woods and also many delights,

the mosquito is not to be classed among them. I am told there are two

kinds, one with and one without "a sing." The latter is said to do the

dastardly and deadly work, but all mosquitoes look alike to me. Where

you are unaided in an effort to exterminate these pests you have almost

as much hope of success as a fly on sticky paper. Yet if you will cruise

around the camp for a few rods you will find many breeding places that

might as well not exist. One day's work with these places convinced me

that I could earn a considerable amount of peace for the season by

carefully filling up every hole where water collected, even for a short

period; in hollow stumps, depressions in the rocks, etc. When it was

impossible to fill these up, a small quantity of crude oil was allowed

to spread across the surface. A gallon will spread over acres in swamp

land, and if the dose is repeated every three weeks it proves most

discouraging to the mosquito. A neglected tin can with an inch of water

in it will become the hatchery of some millions. Water is absolutely

necessary to the hatching of mosquito eggs.

If you wish to induce the

ducks to make longer stays with you, and to invite their friends also,

plant wild rice in the shallow water along the shores of the coves or

nearby stretches of still water. Perhaps you have tried planting this in

the past, at no little expense and trouble, and have not yet had the

satisfaction of seeing the first spear appear. The secret is this: the

seeds should never be allowed to dry. There are places where this seed

can be purchased which has been kept in water from the moment of

gathering, and which will be sent you packed in damp moss. This seed

will almost invariably grow. To any one practically interested, who will

write me, I shall be glad to give the address.

Upon request, the United

States Department of Agriculture, through its Forestry Bureau, will send

you pamphlets, etc., that will be of the utmost importance if you own

more than an acre or two of wooded land. Wood lots to which the

principles of forestry have never been applied very commonly offer a

good chance for "improvement cuttings." The purpose of such cutting is

to secure heeded material, utilize timber which would otherwise go to

waste, and make room for other trees to grow. In making improvement

cuttings, look especially for two classes of trees in addition to those

already indicated as desirable for removal. These are (1) over-mature

trees which are beginning to decay and will rapidly lose their value,

and (2) "suppressed" trees—that is, those whose crowns have been

overtopped by their neighbors so that they can no longer compete for

room. A few years of careful cutting in your lot will greatly increase

the beauty of your stand of trees. Meantime you will be abundantly

supplied with firewood.

An ice house is almost

necessary where the camp is occupied during the warmer months, and where

you are compelled to rely on a private supply of ice you will do well to

erect a place for its storage.

Ice may be readily kept

in a structure of logs that has been thoroughly chinked or calked,

digging down into the earth if you desire, though a building on the

surface does quite as well, particularly in a woody position, where the

trees give almost continual shade. The door should be made hollow and

the space between filled with sawdust. Ten by twelve feet square and

seven feet to the eaves would be about the right size. A floor should be

made of poles set not too tightly together, to allow a free outlet for

the melting ice. At the peak a small hole should be left for

ventilation, and this should be covered with a screen to prevent

insects, birds and vermin from getting inside.

A neighbor will fill this

house with ice in a day, so that aside from the sawdust and the hauling

of the same the cost is trifling and the advantage great.

In storing the ice the

cakes should be kept six or eight inches from the walls all around and

the space between well packed with sawdust. Then, besides, the cakes

should all be thoroughly packed on every side with sawdust to prevent

their freezing together and also to assist in preserving them.

A boathouse is part of

the equipment of the camp, and may be made an attractive feature, for

with it may be combined dressing rooms for the bathers, to say nothing

of an outlook from a balcony. The height of the water even on lakes is

constantly changing, and this demands a float to make the landing of

canoes or the embarking into launches easy. The raft idea may be

employed, though it should be remembered that the float must be drawn

out of the water during the winter, and logs are much too heavy to

handle. Casks are the thing, and with a little ingenuity they may be

framed in such a manner that the whole float may be readily taken apart

and drawn ashore.

Put a roller on the end

of the float, so that canoes or rowboats may be drawn up on it with as

little damage as possible, and it would not be amiss to pad a portion of

the edge of the float with cushions of burlap or canvas stuffed with

soft material, to act as fenders and save the paint and varnish. A

gangway will lead from the float to the boathouse, and a small padded

truck will facilitate the matter of getting the floating stock under

cover away from the weather. |