|

March Dust—Moons of Mars— Planetoids—Occultation of Alpha

Leonis—Zodical Light-Snow

Bunting—Old Gaelic Ballad of "Deirdri:" Its Topography.

If for

the first few days March [1878] seemed inclined to emulate the peaceful

calm and sunshine of its predecessor, it very suddenly assumed a more

warlike aspect; a change came over the spirit of its dream; it became

boisterous and rude; snow, and sleet, and rain, and storm battling in

wild comminglement. It still continued what is called " open " weather,

however; there was no frost, no razor-edged and biting winds, and

vegetation was rather temporarily checked than seriously hurt or

hindered. After this wild burst, in vindication, it is to be presumed,

of the month's right to be called after the bellicose Mars, things

slowly but steadily improved, and the weather is now such as permits us

to get on with our spring work uninterruptedly

and pleasantly enough. "We have not yet, however, had a sufficiency of

the "March dust," so proverbially invaluable at seed-time; and nowhere

perhaps so invaluable, so absolutely essential indeed, in its proper

season, as in the "West Highlands. The day, however, is now lengthening

apace, and with a bright warm sun

overhead, and brisk north-easterly breezes, we shall doubtless soon have

dust enough and to spare.

Our reference to Mars the war -god,

reminds us that Mars the planet, with whose fiery effulgence every one

is familiar, has recently had an accession of dignity such as the

old-world star-gazers never dreamt of in connection with the ruddy orb.

It is found to have at least two attendant

moons, small, and so exceedingly difficult of detection even by the aid

of the best instruments, that it is only under the most favourable

circumstances that they can he observed. It is more than suspected that

a third, and even a fourth satellite, exists, and the planet will in

consequence be subjected to the closest possible scrutiny at all the

observatories at home and abroad for some time to come, in order to

determine with certainty the number of its attendant moons, and whether

they be two or more, to decide their sidereal revolutions, their

diameters, masses, and inclinations of orbits. By reason of his retinue

of satellites, Mars is now exalted to equal dignity with Jupiter,

Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; and by the discovery another point is

scored in favour of the nebular hypothesists. It was on the night of the

1st January 1801 that the first of the planetoids, Ceres, was

discovered by Piazzi of Palermo. Next year Olbers of Bremen discovered

the second planetoid, Pallas, and

so constant and searching has been the scrutiny to which the planetoidal

zone, situated between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, has been

subjected, that the number of these minor worlds is now no less than

182, the last three in the series, Nos. 180, 181, and 182, having been

discovered since the beginning of February last. Of these three, two

were discovered by French observers; the third by Professor Peters of

Hamilton College, U.S., America. This last, however, is suspected to be

only a rediscovery, so to speak; to be identical with Antigone, discovered

five years ago by the same indefatigable observer. If this be so, the

asteroidal series amounts at present date to 181. In favour of the

ingenious hypothesis that accounted for the existence of these minor

orbs by suggesting that they might be the fragments of a large disrupted

world—of a large planet rent asunder by some terrible internal

convulsion—a great deal could be said while the number of fragments was

under half a dojcen or even double that number, but when the fleet of

orblets began to be counted by the score, the disrupted world theory was

dropped as no longer tenable in the circumstances. The hypothesis of

Olbers, however—for it originated with the discoverer of Pallas —led

to a great deal of curious research that resulted in no little gain to

astronomical science; and if it had to he given up as insufficient in

the case of a planetoidal zone, it left us a legacy that may yet he

turned to good account, that such a catastrophe, namely, as the

disruption of a planetary world into fragments that in the shape of

minor orbs would continue to revolve in orbits coincident with that of

the parent globe, is not only possible, but, under certain easily enough

conceivable circumstances, a probable enough occurrence.

Occultations by the moon of planets and first magnitude

stars are always interesting phenomena, and for many years we have

rarely missed observing such conjunctions as they became due, even if

the hour was otherwise inconvenient, if only the weather chanced to be

favourable. Last week there were two occultations, which for particular

reasons we were very anxious to observe, and as the weather was clear

and bright we had but little fear of disappointment. The stars to be

occulted were Alpha and Delta Leonis,

the one on the night of the 16th, the other on the night succeeding. Alpha Leonis

is of the first magnitude, distinguished, like some others of its class,

from the mere alphabetical order of stars by its proper name of Regulus. Up

to within a quarter of an hour of the computed moment of occultation or

disappearance of the star behind the moon's disc, the sky was clear; and

as we stood at our post everything promised a highly satisfactory and

successful observation; but alas, as the moon and star, in nautical

phrase, were close aboard each other, a huge bank of cloud, driven by a

north-westerly breeze, swept over the scene, effectually occulting moon

and stars alike from the most penetrating gaze. It was provoking enough,

but there was no help for it. An observer in our climate must make up

his mind to frequent disappointments of this kind. We were still in

hopes that although the immersion was thus hidden from us we might he

more fortunate in the case of the emersion—the reappearance, that is—of

the star on the moon's western limb. But it was no use. Two or three

times, indeed, the moon shone forth for a minute or two together from

through an old cathedral porch-like rent in the intervening wall of

cloud, but only to be agam obscured; and thus it continued so

tantalisingly promising, that we stood to our post until a glance at the

clock showed that the moment of emersion was already past, and it was

useless waiting or watching any longer. The great object in closely

watching these occultations is to observe, with all possible certainty,

if there is any distortion or momentary projection on the moon's disc of

the planet or star occulted at the instant of immersion and emersion, in

order to decide if the moon has an atmosphere or not. We have seen

enough, we think, from our own observations during the last five and

twenty years, to lead us to the couclusion that such distortion and

projection is occasionally to be seen, and that therefore, contrary to

the general belief of astronomers, a lunar atmosphere very probably

exists, though it may be of greatly less weight and density than our

own. Looking over our astonomical note-book, we find that the winter

just past— let us hope that at this date we may so speak of it—was

remarkable for two things—the almost total absence, namely, of auroral

displays, and the exceeding brilliancy of the zodiacal light. We have

only two recorded instances of the occurrence of the aurora borealis,

both in December, and both but partial, faint, and ill-defined. The

zodiacal light, on the contrary, was remarkably bright and noticeable on

almost every evening in February and early March, its apex reaching up

to and beyond the Pleiades, and with an outline clear and sharply

defined as ever was sheaf of the brightest auroral light. So noticeable

was it on several occasions, that all the people of the hamlet began to

speak about it, and inquire what it could mean, for its perfect

quiescence, its appearance night after night in the same quarter of the

heavens, and the absence of anything like accompanying storms or aerial

disturbance, satisfied even them that it was not the fir-chlisor

" merry-dancers " as they used to know them. Let us assure our Celtic

readers that an attempt on our part to explain the nature of the

zodiacal light in Gaelic was

no easy task; and if the truth were known, we fear onr prelection quoad

hoc was

a sad failure.

We have received the following note from "A Constant

Reader:"—

"Sir—Would you kindly let us know, through the columns of

the Inverness

Courier, the

proper name of the accompanying little bird, and what part of this

country it is properly a native of. It is never seen in Ross-shire but

during very heavy snow, and then they fly about in large flocks, and

disappear again as soon as the snow is gone.—I am, yours respectfully,

"A Constant Reader."

Neatly packed in a couple of lucifer match-boxes

ingeniously conjoined, the bird reached us, and the locale of

its being shot or captured we can only approximately indicate by the

fact that the package bore the post-mark "Garve" There was no difficulty

in at once recognising the bird as the snow-fleck or snow hunting, the Emberiza

nivalis of

Linnaeus, a common enough bird in early winter over the whole of

Scotland. Although it has been known to breed in Scotland, a few being

found all the year round along the summits of the Grampians, and other

mountain ranges to the north and north-west, it is probably a bird of

considerably higher latitudes than ours; visiting our shores as a

migrant in October or November, according as the winter is early and

severe or otherwise, and leaving us again in March or April. It is a

hardy little bird, of plain and rather sombre plumage, prettiest in the

act of flight, when the white on the edges and tips of the

tail-feathers, and quills, and secondaries, comes out in pretty bars,

contrasting pleasantly with the dark and chestnut brown, which may be

said to be the prevailing colour. The snow-fleck has hardly any song

beyond a tremulous twittering, and a few call-notes so loud and shrill

that in the strange and solemn calm that sometimes precedes a

snow-storm, they may be heard at a great distance. Our correspondent

should have stated where, when, and how the bird was got, a knowledge of

such matters vastly enhancing the interest and value of a specimen,

especially if it has any claims to be accounted a rara

avis.

We are indebted to our excellent Celtic friend, Mr.

William Mackay, Inverness, for a copy of his exceedingly interesting

monograph on The

Glen and Castle of Urquhart, one

of the most interesting spots in the Highlands. Mr. Mackay attempts to

make Glen Urquhart classic ground by associating the story of Dearduil

and Clann-Uisneachean, as related in the mediaeval Gaelic ballads, with

the locality, by pointing out that there is a Dun Dearduil in

the neighbourhood—a place so called after the hapless heroine of the

ballad story. But in the old and unquestionably authentic ballads her

name is not Dearduil but Deirdri

; Deirdir and Daordir. Dearduil

is a much later form of the name, not older, Mr. J. F. Campbell hints,

than the Darthula of "Ossian" Macpherson. But there are other Dun

Dearduils besides that referred to by Mr. Mackay; one, for instance,

near us in Glenevis; and it is to be observed that all the places so

called are vitrified forts. An old man in our neighbourhood, one of our

best seannachies, always

speaks of the Glenevis vitrified fort as Dun Dearsail or Dearsuil, and

this is probably the correct form of the term, closely connecting it

with dears and dtarsadh,

to shine, a shining; to beam and be etfulgently aglow like flame of fire. Remembering

that all the

places so called present more or less marked traces of vitrifaction, in

the formation of which fire and flame, on

a large scale, must have been the chief and most remarkable agents, the

name comes to have a fitting and appropriate enough meeting, without the

necessity of taking in the name of Deirdri or Dearduil at all. Mr.

Mackay next gives a translation of a couple of quatrains from the oldest

known version of the Clann-Uisneachan ballad; that, namely, of the

vellum manuscript in the Advocates' Library, bearing the date 1238, and

quoted in the Highland Society's Eeport on Ossian

:—

"Beloved land, that eastern land,

Alba, with its lakes;

Oh, that I might not depart from it;

But I go with Naois.

Glen Urchain, O Glen Urchain,

It was the straight glen of smooth ridges:

Not more joyful was a man of his age

Than Naois in Glen Urchain."

Mr. Mackay will have it, of course, that this " Glen-Urchain

" is his Glen TJrquhart. The Gaelic name of Urquhart, however, is

invariably a trisyllable; but this apart, the Glen-Urchain of

Mr. Mackay has no existence in the ballad from which he professes to

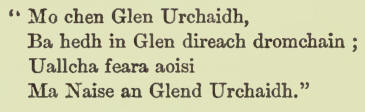

translate. The quatrain stands thus in the original :—

It is Glen Urchaidh, observe,

not Urchain; the

Glenurchay of Argyllshire, in short, not the Glen Urquhart or Urchadan

of Inverness-shire. This is further proved by the context, the

immediately preceding and succeeding stanzas, which speak of Glen Mason

and Glendaruel in Cowal; of Duntroon; of Innisstry-nich on Loch Awe; of

Eite or Etive, &c. In so far, in short, as this story of

Clann-Uisneachan of Ireland has to do with Scotland, we find it

connected with Argyllshire, where indeed we should most naturally look

for it; and chiefly with Glen Etive and Loch Etive, where we have Dun-Mhac-Uisneachan;

Grianan Dheirdir; Caoille Naois; Eilean Uisneachan, &c. &c. In

Argyllshire, too, it was that the Clann-Uisneachan hallads were

preserved till discovered and taken down from oral recitation hy the

collectors. And if Dun-Dearduil and "Glen-Urchain" must he given up as

having no connection with the ballads in question, so would it seem to

follow that some other etymology than any connection with the name of Naois, must

be found for Loch Ness, Inverness,

&c. |