|

Overland from Balluchulish to Oban on a

'Pet

Day' in February—Story of Clack

Ruric— Castle

Stalker: an Old Stronghold of the Stewarts of Appin—James IV.—Charles

II.— Magpies—Dun-Mac-Uisneachan.

With all

their tendency, in their every reference to the past, to become laudatores

temporis acti, the

sturdy upholders of the superiority of all that was, in

comparison with anything and everything that is, our

weather-wise octogenarian friends "here are all agreed that so

summer-like a February [1878] month they never knew before. It is true

that in making this admission they shake their heads sapiently, and hint

that no good can come of such an unnatural commingling of the times and

seasons. It will be well, they add, if before cuckoo day (mun

d'tliig latlia na cuaig) we

haven't to pay for it all in the shape of storm and cold at a time when

these are as unseasonable and out of place as is summer calm and summer

sunshine now. It

was amusing to see these honest old croakers selecting the coziest nooks air

chid gaoitlie's air aodain greine, as

the Fingalian tale has it,—that is, at the back of the wind and in the

face of the sun—and thoroughly enjoying the calm and sunshine at the

very moment that they would impress upon us the unnaturalness and

unseasonableness of it all. The first fortnight of February was, indeed,

wonderfully fine; from the beginning of the month up to the evening of

St. Valentine's Day, more like the close of April or early May than

anything usually looked for while the sun is still in Aquarius. Driving

overland to Oban on the 11th, and, by the ferries of Ballachulish, Shian,

and Connel, a very beautiful drive it is, hardly to be equalled

elsewhere even in the West Highlands; the day was so bright, and calm,

and clear, that while mavis and merle, and hedge-accentor and chaffinch

greeted us from copse and hedgerow with their rich and mellow song, the

driver, sitting heside us, couldn't help observing as we passed by Appin

House, "Na 'n robh chuag again a nis, bha 'n samhradh fhein ann!" "If we

had but the cuckoo now, it would be summer its very self!" On the beach,

a little above high-water mark, just under Appin House, and within an

easy stone's cast of the public road, there is an immense spherical

boulder of granite, to which there is attached a curious old story,

which invests with additional interest an object deserving enough of

attention for its own sake—for the sake, that is, of its huge size and

almost perfect spherical form, this latter peculiarity, in the huge

solid mass, making it the most remarkable thing of the kind on the

mainland, at least of the West Highlands. The story of the Appin House

boulder, or Clach

Ruric as

it is called, is, dropping minor and unessential details, to the

following effect:—Long, long ago a Prince of Lochlin or Scandinavia,

with a formidable fleet of war galleys, made a descent upon the

Hebrides, killing and plundering everywhere with a ruthlessness known

only, even in those days of rude lawlessness, to the Yikings of the

north. Having thoroughly devastated the islands, Ruric—for such was the

Prince's name— steered for the mainland of Morven, and took up his

residence in the castle of Mearnaig, in Glensanda. In this stronghold,

the ruins of which still exist, he resolved to pass the winter, with the

intention of over-running and plundering the adjoining districts in the

spring, and afterwards sailing homewards in the calm of summer seas, for

his galleys were so deeply laden with booty that he feared to encounter

the turbulence of the North Sea at any other season. In the early spring

the cruel Northman was betimes astir, killing and plundering with but

little opposition throughout the districts of Kingerloch, Sunart, and

Ardgour, to the head of Lochiel. While of his numerous fleet a single

galley showed more than a foot and a span (troidh

agus reis were

the words of the narrator) of gunwale unsuhmerged, Euric was

unsatisfied, and to complete his ill-gotten freight he resolved on the

plunder of the opposite district of Appin, the smoke of whose dwellings

could he seen, and the lowing of whose numerous herds could he heard

(when the summer morning was still and the Linnhe Loch was calm) hy the

pirate prince from the battlements of the castle of Mearnaig. One

morning Euric anchored his galleys in the Sound of Shuna, and landing,

erected his tents on the green knoll now occupied by Appin House. "With

this spot as his head-quarters, it was his intention to plunder the

district north and south of him at his leisure, believing that he would

meet with as little opposition here as he had already met with

elsewhere. The inhabitants of Appin, however, were partly on their

guard, and determined to resist, and if possible chastise, the invader.

And first conveying their old men, women, and children, with their

flocks and herds, into the fastnesses of the upland glens, they resolved

to watch the movements of the Norsemen, ready to fall upon them whenever

a favourable opportunity should offer. That same night, as some cattle

herds, acting as scouts, were on the hill immediately above the tents of

the invaders, one of them directed the attention of his companions to a

huge granite boulder with so slight a hold of the hill crest, that, with

some little labour, it might be let loose at any time—a terrible

messenger of wrath—amongst the tents of the enemy below, whose shouts of

laughter at that moment, and snatches of rude song, proved that they had

feasted plentifully and had no apprehenson of immediate death or danger

in any form. After much labour, the herdsmen managed so to dig about and

undermine and loosen the boulder in its bed on the hill-face, that, on a

given signal, their united strength sufficed to tilt it headlong over

the steep, leaping and thundering on its terrible path. The largest

trees in its course snapped before the boulder like reeds: when it came

into momentary contact with a rock, the sparks flew heavenward as if

from an exploded meteor ! In a dozen of bounds it reached the tents of

the Norsemen, crushing, mangling, grinding into pulp or powder (a pronnadh

agus a bruanadh, are

the Gaelic words) everything it touched, and finally stopping where it

now stands, to be long regarded by the people of the district with a

feeling akin to superstitious awe, and to he known by the name of Clach

Ruric. In

the morning, the Norsemen could only know by the mangled fragments of

their bodies that their Prince, with his two sons, and many of those

next to him in power, had met with a terrible death. Before the Appin

men could gather in sufficient force to attack them, the Norsemen

unmoored their galleys, chanting the death-song of their chief as they

unmoored, and set sail for Lochlin, never more to trouble the mainland

of the West Highlands with their invasions. The venerable seanachie from

whom we picked up this tradition, added that Castle Coefin, or

Cyffin, in Lismore, is so called after a Danish prince of that name, who

also was connected with Ruric's expedition, though in what manner he was

unable to say.

Not far from Clach Ruric, on an island rock in the

entrance to the Sound of Shuna, are the ruins of another castle, of a

later date, however, and more recent interest than can be attached to

the many strongholds of the Viking period perched on the rocks and

promontories of this part of the West Highlands. This is Castle Stalker,

or, in the language of the district itself, Caisteal-an-Stalcairc, the

Castle of the Falconer or Fowler. The small rock-island on which it is

built is Sgeir-an-Sgairbh (the

sea-rock, or skerry of the cormorant), from very early times the

gathering cry at once and rendevous of the Stewarts of Appin in all

their maritime expeditions. Castle Stalker dates from about the

beginning of the reign of James IV., for whose convenience and

accommodation, when, as frequently happened, he extended his hunting

expeditions to this district, it was built. Stewart of Appin, who was a

great favourite with the king, was appointed hereditary keeper, and the

castle continued in the possession of the family until, about the year

1645, the Mac Ian Stewart of that date, in a moment of drunken folly,

made it over to his wily neighbour, Donald Campbell of the Airds,

receiving in return the handsome and adequate equivalent of an

eight-oared birlinn, or

small wherry! Stewart, when sober, would have gladly cancelled so

manifestly one-sided a barter-bargain at any sacrifice, but Campbell,

having got possession, kept it; while the disgraceful transaction so

stung the pride of the Stewarts that they practically deposed the Baotliaire (the

silly one), as they nicknamed the chief, from his chieftainship, by

unanimously electing his cousins of Invernahyle and Ardsheal to be their

leaders in the subsequent wars of Montrose. For a short time during

Montrose's ascendancy in the Highlands, and for a longer period towards

the close of the reign of Charles II., Castle Stalker was again in the

possession of the Stewarts; but at the Revolution the Campbells had it

all their own way; they repossessed themselves of the castle, and it has

remained theirs ever since. About forty years ago a gentleman of the

family of A-ilein

'Ic Rob of

Appin, who had amassed a considerable fortune in the West Indies,

offered the then proprietor a largo sum for the bare rock and ruins of

Castle Stalker, but the offer was refused.

From the wooded knoll to the left, as we entered the

village of Portnacroish, we heard some notes that,' harsh as they were,

delighted us, for we had not heard them for many years; and the reader

will perhaps smile when we confess delight in association with what was

neither more nor less than the chattering of a pair of magpies! Knowing

that it must be magpie chattering and nothing else, though the lively

confabulators were for the moment invisible, we got out of our

conveyance, and on reaching an open glade we got sight of a pair of

these beautiful birds perched on the topmost bough of an old ash tree;

and so busy were they in the discussion of what must have been a matter

of grave and immediate importance, that the usually shy and wary birds

did not notice our approach till we were quite close upon them, when,

with a scream of alarm and an indignant flirt of their tails, they

glided in graceful curve, rather than flew, over the tree tops and

disappeared. So rare has the magpie become in Lochaber and the

immediately surrounding districts, that a sight of a pair of these

handsome and sagacious birds delighted us exceedingly. We had little

difficulty in concluding that their lively chattering on that bright and

beautiful morning was about no less important a matter than the

propriety of at once putting their house in order and setting about the

labours of incubation. If there were any truth in popular superstition,

that particular day ought to have afterwards turned out a disagreeable

one to us; for had we not seen two magpies

together, and what is more, did we not go out of our way to see them,

when we might have easily passed on unseen of them, as they were

invisible to us? In the south of Scotland the old pyet rhyme is

something like this—

"One's joy,

Two's grief,

Three a wedding,

Four death.'

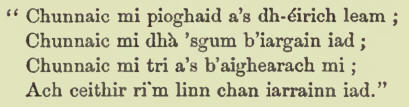

In the old sgeulachd the

Gaelic rhyme is of similar import—

In our own case, on that particular occasion, the

superstition could not have been more completely falsified by the event,

for, maugre the magpies, our trip to Oban was in its every circumstance

as agreeable and pleasant as it could well be. What a pity it is that

these beautiful birds, whose favourite residence, too, if they were only

permitted to live in peace, is the immediate vicinity of human

dwellings, should be of su'ch evil repute that gamekeepers everywhere

consider themselves justified in accomplishing their utter destruction

by every means in their power. Their utter destruction

we have said; and it is only as to their total extirpation that we would

venture on a word of expostulation with gamekeepers and their employers.

It is true that the magpie is an enemy to winged game, being a cunning

and persistent nest-robber, an adroiter sucker of eggs than the

proverbial " grandmother" herself. That the gamekeeper should therefore

dislike them is the most natural thing in the world, and that, in

gamekeeper's own phrase, they should " be kept down " is proper enough.

But we cannot agree that it is necessary that the bird should be utterly

destroyed. Here and there on a wide estate an occasional pair of magpies

might surely be tolerated for the sake of their beauty and amusingly

lively manners, and on the divine principle of "live and let live." For

our own part, in approaching a gentleman's residence, the sight of a

pair of these birds flitting about " the old ancestral elms " always

intensifies our respect for the place and the owner.

Crossing Loch Creran, by the Ferry of Shian, we are in

Bender-loch—classic ground, and archoeologically the most interesting

spot, perhaps, in all the West Highlands. "Everything here is

beautiful," says Dr. Macculloch. "The distance between the ferries of

Shian and Connel is but five miles; but it is a day's journey for a wise

man." About half-way is Dim-Mac-Ulsneachain (the

Fort of the Son of Uisneach),

one of the most interesting of our vitrified forts, qua such,

and supposed to be the Beregonium of Hector Boethius, and the site of

the still older Selma, the "Hall of Swords" of Ossianic song. That it

was a place of importance long before the time of the Dalriad Scots

seems very certain ; and, leaving Macpherson's "Ossian" altogether out

of the question, there occur in the old Fingalian ballads, and tales of

the Feinne, about the antiquity of which there has never been dispute;

numberless local references which seem in a very remarkable manner to

point to this spot as the principal stronghold in Scotland (for they

were of Ireland also) of the Fingalians at one period, and that the most

important, perhaps, in their history. "Within a short distance of

Dun-Mac-Uisneachain, and commanding it, is a steep, rocky eminence of

considerable height, called Dunvallary or Dunvallanry, the etymology of

which may be

Dun-bhaU'-n-ru/h, the

Fortified Place of the King's Town; or Dlni-bhaiV

n \'fhrith, the

Fort of the Town on the verge of the Hunting Forest. Stretching away

towards Connel and Loch Etive is the wide moorland flat of Achnacree,

which, with its numerous cairns, Druidical circles, monoliths, and other

relics of the olden time, may very well be the ancient "plains of Lora;"

Lora itself, frequently mentioned in Ossianic poetry, and meaning Luath

shruth, the

loud, swift current, par

excellence, meeting

us face to face, so to speak, in the turbulently impetuous rapids of

Connel. |