Conscious at

last that pouting and inordinate weeping became him not, and that, being

constantly on the "rampage," like Mrs. Joe Gargery, was hardly

consistent with his place in the calendar, April [1869] betimes resolved

to "tak a thocht and mend," and now, like Richard, is himself again—all

sunshine and smiles. The rain-gauge, to be sure, with stern

impartiality, will still show an occasional " inch," or parts of an

inch, if you are very particular in your inquiries, when examined of a

morning, but its readings now at least are in no way appalling, for they

represent the warm and genial rainfall of April showers, that, after

all, are as necessary on the west coast at this moment, and as

refreshing to the soil, as the orthodox cup of mulled port of an evening

was believed to be to the weary traveller in the good old days of

stage-coaches and post-chaises. The country, at all events, is looking

very beautiful just now, everything so green and glad, so fresh and

fair, and full of promise of a yet gladder, and gayer, and brighter day

at hand, when the swallow, twittering, shall dart, a glossy meteor, in

the sunlight, and the cuckoo shall challenge the truant schoolboy to

repeat its well-known notes, correctly if he can. Now is the time to

hear our native song-birds at their best, warbling their sweetest

strains, and to decide, once for all, if it be possible, which you like

best; the loud, clear, silvery tinkle of the seed-shelling fmch's rich

and rapid song; the liquid and mellifluous warblings of the soft-billed

tribes; or the soul-entrancing, round, rich, flute-like piping of the

throstle, song-thrush, and merle. How it may fare with the reader who

trios to decide the point we cannot say. For our own part, no decision

that we could ever arrive at could keep its legs for two days together.

No sooneT did

we decide that the skylark and its congeners had the "best of it, than

the goldfinch, with a score of lively cousins to aid and abet,

challenged the verdict, and forced us to acknowledge Ida exquisite

mastery in song—an admission made, however, only to he retracted again

almost as soon as made, for in our walk on the evening of that self-same

day did wrc not stand, and for the life of us couldn't help

standing—breathless, and hushed, and still—to listen to the merle and

song-thrush from the neighbouring copse pouring forth the indescribable

riches of their God-taught vespers as the sun went down; and did we not,

then and there, vow, in utter forgetfulness of finch and skylark; that

no music of earth could for a moment compare, in execution and compass,

in distinctness, and cheeriness, and purity of note, with these

matchless twilight strains! The truth is that no music is equal to

bird-music—wild-bird music, that is—in its season, and amid all its

natural surroundings; and the probability is that we shall give the

preference at any time to the melody of one bird over that of another,

not on any well-defined principles of choice or selection in the matter,

but simply in accordance with our own prevailing mood and temperament of

the moment. Such, at least, has been our own experience ; but the reader

has every opportunity at this season of studying the question for

himself and deciding. Except that of the nightingale, perhaps the music

of no bird has attracted so much attention by its beauty and

suggestiveness as the merry trill of the skylark's ascending song. The

poets of every country in which it is to be found have vied with each

other in their praises of the only bird that sings as he soars, and

soars as he sings, selling on quivering pinions the aerial terraces of

heaven, until he can scarcely be discerned, a music-showering speck

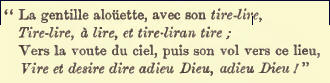

against the back-ground of the blue profound ! The other day we fell in

with some curious verses by the French poet Du Bartas, in which he

strives, and not altogether unsuccessfully, to imitate the merry trill

and rhythm of the skylark's song :—

The last line, if rapidly repeated with the proper beat

and intonation, will be found a really very successful imitation of the

concluding notes of the lark's well-known song. Many of our readers will

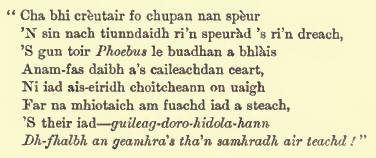

remember that the North Uist bard, Ian Mac Codrum, in his Smeorach

Chlann-Domhnuill, manages

very happily to imitate the smeorach or

song-thrusli's notes in the burden or chorus ; while Alexander

Macdonald—Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair—very naturally falls, like the French

poet, into an imitation of the wild-bird music of the woods and groves

in a stanza that may be quoted not inappropriately at this season :—

The lines of Du Bartas have little meaning in themselves,

and are untranslatable, being simply an attempt on the poet's part, in

some odd moment of hilarity and abandon, to

embody the notes of the skylark's song in something like articulate

verse. The general sense of Macdonald's lines describing the

irrepressible inclination of all living creatures to be jubilant and

joyous at the return of spring, cannot better be rendered than in the

first part of Scott's introductory stanza to the second canto of the Lady

of the Lake, only

that the return of spring in the one case, instead of the return of morn

in the other, prompts to the outburst of gladness and song :—

''At morn the black-cock trims his jetty wing,

'Tis morning prompts the linnet's blithest lay,

All Nature's children feel the matin spring

Of life reviving, with reviving day;

And while yon little bark glides down the bay,

Wafting the stranger on his way again,

Morn's genial influence roused a minstrel grey,

And sweetly o'er the lake was heard thy strain,

Mixed with the sounding harp, O white-hair'd Allan-bane!"