A prohatiim

est Recipe

for Catarrh and Colds—Egg-shell Superstition—Curious old Gaelic Poem.

How intense was the recent frost [January 1875], and how

hyperborean all our surroundings, may be judged of from the fact that on

coming out of church yesterday, one of our people, a greyheaded, pious

old man, spoke of the happy change to open weather and " westlan'

breezes" very solemnly as "the blessed thaw"—an

t'aiteamh beannaichte. Before

any one else north or south of the Tweed made any reference to the

coming winter, our readers may remember that we did, and that we

inculcated on every one the wisdom of keeping themselves warm and

comfortable, by means of good fires and otherwise, as the best way of

being jolly in the best and truest sense of that much misapprehended and

frequently misapplied term. It was, in truth, a trying season; but

sensibly and thickly clad in many a fold of honest home-spun curain, or

plaiding, our people for the most part got over it without any very

serious ailments. Influenzas, catarrhs, and colds in every form were of

course common, and, for a time, one was met on every side by an

uncomfortable and sometimes disagreeable amount of coughing,

expectoration, sniftering, sneezing, and nose-blowing; but now all this

has almost or altogether passed away, and people are again going about

as usual, clad no otherwise than ordinarily, and as becometh the

inhabitants of a temperate zone: plaids, comforters, double-ply mittens,

and "bosom-friends," having been laid aside as unnecessary incumbrances

in weather that is now actually warm and spring-like, as compared with

that dreadful month or six weeks of Baffin's Bay-like temperature, that,

when it got fairly at you, and off your guard, seemed capable of making

the very hlood freeze in one's veins, even as it froze the water in our

subterranean and best guarded lead pipes. Nothing, perhaps, could more

pointedly illustrate the healthy vigour and vitality of our people

generally than the fact that, although we have amongst us many who have

arrived at extreme old age, and some who have been more or less

valetudinarian for years, there has not been a single death in the

district—a district which, as we look around us, contains some two or

three thousand inhabitants—since the beginning of last December; a fact

which, considering the inclemency of the weather, and the high

death-rate everywhere else, is something surely worthy chronicling. "We

are probably correct in believing that the worst at least of winter is

already past, but much cold and stormy weather may be still in store for

us, and as colds and coughs may return, we beg to make friendly offer of

the following prolatum

est recipe,

quite a popular cure in this part of the country for every form of

winter influenza. Cure or no cure, the recipe has at all events the

merit of being extremely simple, and to thousands of our readers very

readily available at any time. Take a pint—say a tumblerful—of sea water

that has been heated to the boiling-point, without having been allowed

actually to boil. Sprinkle over it some pepper, rather more plentifully

than you do in your soup ; drink this as hot as you can bear it as you

step into bed at night. Next day your cold and cough will have

disappeared like an unpleasant dream. You may be weak, but you will,

upon the whole, be well! We cannot personally vouch for the efficacy of

this draught, but we find that many people here invariably resort to it

as a ready and popular cure for their colds, and they speak highly of

its virtues, and, contrary to what one would expect, of its comparative

pleasantness and palatability as well. A sensible old man whom we

questioned on the subject a few days ago, and a firm believer in the

efficacy of this " saline" draught, told us in confidence that the rationale of

the thing consisted in the fact that it immediately acted as a powerful

sudorific; and that to this, he thought, was to be attributed the

thoroughness as well as the rapidity of the cure. Probably he was right.

It is a simple, cheap, and readily available remedy at all events, and

dwellers by the sea-side might do worse than give it a trial at a pinch,

when more orthodox remedies have failed, or are not ready to hand. One

grand thing about it is the certainty that, if it does no good, it

cannot possibly do harm. Another old man in our neighbourhood, still

hale and active, though in his eighty-fourth year, told us lately that

he never took a dose, not a ha'penny's worth, of medicine, druggist's or

doctor's stuff in his life. "Whenever I felt out of sorts," he

continued, "I just went down to the sea and drank a good large draught

of salt water; that was

always my medicine,

and it never once failed to do me good." So that there may bo more

virtue in sea water as a curative agent in bronchial and stomachic

ailments than the world generally wots. And if so, how consoling the

thought that this druggist's

shop is never shut; the supply is exhaustless, and no charge!

A curious bit of popular superstition is the following,

which a gentleman in a neighbouring district was good enough to bring

recently under our notice. After breakfast, at which, among other good

things, we had some excellent fresh eggs, he suggested that we should go

into the kitchen to smoke, "and watch," he said, "what my housekeeper

will do with the empty egg-shells as the breakfast things are brought up

from the parlour." We went and stood and watched accordingly, and this

is what we saw, chatting with our host the while, that the housekeeper

might not suspect that we took any particular interest in her doings. We

noticed that when the girl came into the kitchen and laid the tray upon

the table, the housekeeper, a staid and respectable-looking woman, well

advanced in years, walked over and took the egg-shells—there were four

or five of them—and, placing them one after another into an egg-cup, she

took a small knife, and passed it with a smart tap through the bottoms

or hitherto unbroken ends of the lot, and then turned away to some other

employment. This was all, for our host immediately suggested that we

should visit the stables. We were a good deal puzzled, having seen so

little, where we. expected to have seen a great* deal, and that little

so seemingly without meaning and purposeless. When we got to the

stables, our host asked if we understood the meaning of the old lady's

manner of dealing with the egg-shells. We confessed our profound

ignorance, having never seen—never, at least, seen so as seriously to

notice—anything of this kind before. "My housekeeper, you must know,"

continued our friend, "is a most excellent woman, but much given to

little superstitious observances and harmless giosragan. She

will not allow a single egg-shell to go out of her sight without first

making a hole through it, knocking out its bottom in short, in case, as

she has more than once seriously told me, a witch should get hold of it

and use it as a boat, in which to set to sea in order to raise violent

storms, in which the ablest seamanship could not possibly save hundreds

of vessels from being miserably wrecked!" "You may smile," he went on, "

for it is supremely absurd, to be sure, that an otherwise sensible woman

should give credence to such nonsense; but, after all, if you make

inquiry, you will find that the superstition in question is quite a

common one. Few middle-aged women, brought up in the Highlands, but will

act as you saw my housekeeper act with the empty eg^-shells, knocking a

hole through their unbroken ends before throwing them aside, or

frequently even more effectually providing against the possibility of

their being used as witched life-boats, by crushing the whole shell into

a crumpled mass bodily in the hand." "We haven't as yet had many

opportunities of making inquiry into 'the matter, but from all we can

gather from some old women in our neighbourhood, we believe empty

egg-shells are, or perhaps we should say were, frequently treated after

the fashion stated, and for the reason assigned. Some of our readers in

the north-west Highlands and Hebrides may perhaps know something more

about a very odd and curious superstition to be met with in the latter

half of the nineteenth century. For obvious reasons, it is a

superstition more likely to be prevalent among islanders and dwellers by

the sea-shore than in the more inland parts of the country.

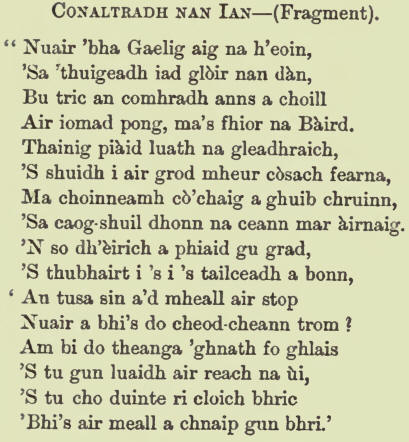

The following fragment of a curious old poem we picked up

about ten days ago from the recitation of Alexander Maclachlan,

shepherd, Dalness. It is unfortunately but a fragment, as we have said,

but we give it here in the hope that some of our friends of the Gaelic

Society, or of our many readers throughout the Hebrides, may be able to

supply more or less of the remainder. Maclachlan heard the entire poem

from a Glenetive forester, a very old man, some years ago, but this man

is now unfortunately dead, and the reciter could not direct us to any

one likely to be able to repeat the poem at length. Perhaps our friend

Mr. J. F. Campbell of Islay, so indefatigable and marvellously

successful in his search after Celtic song and story, "all of the olden

time," may have met with it in a more or less complete form; if so, he

would very much oblige us all in the north by giving us a version of it

and its history, as far as he knows it. WTo may state that it

does not appear in Leabhar-na-Feinne, which

we have searched for it, though unquestionably a production of

considerable antiquity. Maclachlan told us that the old forester, in

reciting it, called it Conaltradh

nan Ian, or The

Parliament of Birds. The

following were evidently the opening lines of the poem, and likeliest to

be remembered by one who only heard it repeated once or twice :—

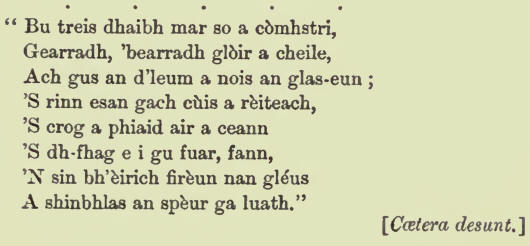

This curious poem seems to have been throughout of a

dramatic form. Maclachlan says that, as he heard it repeated, almost all

our better known wild-birds were introduced, and had appropriate

speeches and parts assigned to them. He particularly referred to a very

funny Speech by the wren, who finally quarrels with the wagtail, by whom

he had been insulted, and gives him a good licking. The end of it all is

that the eagle is unanimously elected king of birds, with the glas-eun

or falcon-kite as his lieutenant. The throstle cock is elected bard of

birds, and the dipper admiral and commander-in-chief of the wild-bird

fleet. Any one recovering the whole poem would be conferring no small

boon on Gaelic literature.