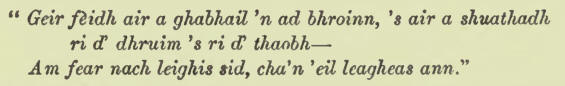

That is—the fat of deer applied internally and

externally, the invalid whose sickness that does

not heal, why, then, there is no healing for him. The old Highlanders,

you see, knew the value of deer : they hadn't a good word to say of

sheep.

A few days ago we went into a cottage where a woman was

sitting spinning, and singing a song we had not heard for many years,

though we recollect hearing it frequently sung in hoyhood. The soft and

plaintive air was an old favourite, and her style of singing pleasing.

With a very sweet voice and much feeling, she sang it all on requesting

her to do so ; and after tea in the evening we threw the verses into

English, as follows. It is, however, rather an imitation than a

translation. The original, which is probably known to many of our

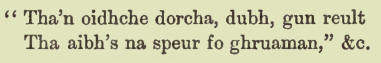

readers, beginning—

is old; how old we know not. Nor have we any clue to the

name of the author, or more probably authoress. Of the authors, indeed,

of many of our very finest Gaelic songs may be said what was said of the

old nameless border-bard, that they—

"Nameless as the race from whence they sprung,

Saved other names and left their own unsung."

The song in Gaelic has no particular title. It is known

by the two first lines quoted above, just as we say, "Of a' the airts

the wind can blaw," and "Ye banks and braes o' bonnie Doon." In default

of anything better, our English version may perhaps appropriately enough

be entitled—

Light and Shade.

Dark and dreary is the world to me,

No sun, no moon, no star;

Vainly I struggle on my midnight sea,

No beacon gleams afar;

A wilderness of winter, frost and snow,

Sad and alone I hang my head in woe.

'Tis vain to strive against the will of fate

(No sun, no moon, no star);

"Where I had looked for love, I found but hate

(No beacon gleams afar);

I gave my heart, my all, to one who cares

Now nought for me—no one my sorrow shares.

Cares not my love though I were dead and gone

(No sun, no moon, no star!)

God help me, I am weak and all alone

(No beacon shines afar):

I dare not reveal my grief, I dare not tell;

The fire that burns my heart no tears can quell.

Traveller that passest o'er hill

(May thy night

have its star!)

Acquaint my love that you have left me ill,

And seen my bleeding scar;

'Twere better to have killed than maimed me thus—

A bird with broken wing in the lone wilderness.

I once was happy, and how bright was then

Sun, moon, and every star!

Spotless and pure I laughed along the glen;

When, swift to mar

This happiness and peace, the spoiler came

And left me all bereft—the child of shame.

And yet I do not hate him, woe is me

(No sun, no moon, no star! )

But shun him, O ye maidens frank and free!

'Twere better far

That you were lifeless laid in the cold tomb,

In all your virgin pride and beauty's bloom.

But God is good, and He will mercy have;

(How bright the morning star!)

Even the weary-laden find a grave—

(The beacon shines afar!)

Bless, Father of our Lord so meek and mild,

An erring mother and a helpless child.

The moral of our song is obvious, though you will observe

the story is told with all possible delicacy and good taste, a

characteristic, by the way, of our hest Gaelic poetry. The reader may

easily understand that, sung in proper time and place, and with proper

feeling, such a song is calculated to have a good effect, and convey a

healthy lesson in its own indirect way, when a sermon or moral

exhortation, however well meant, would he altogether out of the

question. There is much sound sense in Mackworth Praed's Chaunt

of the Brazen Head, the

first verse of which is this—

"I think, whatever mortals crave

With impotent endeavour,

A wreath—a rank-—a throne--a grave —

The world goes round for ever;

I think that life is not too long,

And, therefore, I determine,

That many people read a song.

Who will not read a sermon."

At a hridal, baptism, or other merry-making, such a song

as the ahove is calculated to do more good than the most laboured,

well-meant, and goody-goody sermon that ever was preached. As we rode

away from yonder cottage door, the woman resuming her task, and chanting

a gay and lively air in accompaniment, we were reminded of a verse quite apropos to

the occasion :—

"Verse sweetens toil, howe\er rude the sound:

All at her work the village maiden sings;

Nor while

she turns the giddy wheel around,

Revolves the sad vicissitude of things."

And we also thought of the simple and beautiful epitaph

on the tomb of a nameless Roman matron:—

"Domum mansit, lanam fecit,"

which old Robertson of Strowan has so admirably rendered

into our Scottish Doric:—

She keepit weel the house, and birlt at the wheel!

A discovery of considerable archaeological interest has

recently been made by some people employed in trenching the moss of

Ballachulish in our neighbourhood. At a depth of ten feet in the "

drift" subsoil, underlying six or seven feet of moss, only removed

within recent years in the ordinary course of peat-cutting, was found

the remains of what, in the far past, must have been a flint instrument

manufactory on a large scale. Within an area of twenty or thirty square

yards was disclosed several cartloads of flint chippings, manifestly

broken off in the manufacture of flint instruments, for we have been

able to secure several arrow heads, two roughly finished chisels, and a

hammer head of curious shape, with a hole in the centre, which must have

cost the maker no small amount of time and trouble in the manipulation.

What renders this "find" more interesting is the fact that the material

must have been brought to the place of manufacture from a considerable

distance, flint being of rare occurrence anywhere in Nether Lochaber.

Underlying such a depth of solid moss and drift, such a discovery

necessarily carries us back to a race of men who lived in a very remote

period indeed; how remote, even geology is as yet unable absolutely to

say. We were unfortunately from home at the time the discovery was made,

and were thus prevented from examining the whole in

situ,. This

much, however, is certain, that under a diluvial bed of drift, gravel,

and sand of upwards of two feet in thickness, underlying a thickness of

at least six feet of solid moss, a flint instrument manufactory is

found, the work of a people who lived before the deposit of that drift

and the growth of that moss. How many thousands and thousands of years

ago lived that flint-working race, who, in view of the extreme slowness

of geological changes, can say? We know that in the celebrated case of

the discovery of flint weapons at Abbeville and elsewhere in France the

remains of extinct species of elephant, rhinoceros, and other mammals

were found at an immense depth in the drift alongside of flint

instruments unquestionably fashioned by human hands. Whether our

Ballachulish discovery is to be held as a connecting link with a people

of an antiquity as remote as those of Abbeville, it would be rush

positively to assert; but the flint workers, some remains of whose

labours have, as we have stated, been recently brought to light in our

neighbourhood, must have lived at a period when the face of the country

was geologically very different from what it is now; and remembering how

slowly as a rule geological changes are brought about, we shall probably

be still within the mark, if approximately we fix the era of the

earliest flint workers at something like ten thousand years ago, and in

the case of Abbeville, Continental archaeologists have had no hesitation

in suggesting a still remoter antiquity.