|

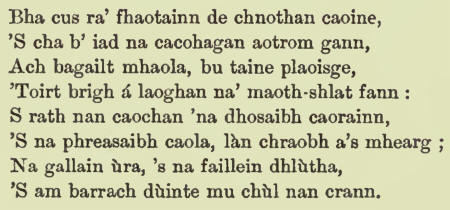

Early sowing recommended—Vitality of Superstitions—Capnomancy—Hazel

Nuts : Frequent References to in Gaelic Poetry—How best to get at the

full flavour of a ripe Hazel Nut.

A fortnight's incessant

rain [September 1872]—rain descending at times in solid sheets—not only

wets the ground and puddles the roads, but makes one's very brains feel

soft and sloppy and mashed-turnip-wise. You take up a book only to lay

it down again. You fill your pipe and set it alight, but with less than

half a dozen whiffs you are more than satiated. The weed has lost its

flavour. You sit down to write "doggedly," as Johnson says, but with all

your doggedness the pen totters over the sheet with pace uncertain and

listless, as if even he felt disinclined for the task, and the

sentences, like a squad of raw recruits, refuse to fall gracefully into

their places, and stumble against each other in ludicrous confusion, to

the consternation and grief of the most patient of drill-sergeants. You

will not, perhaps, believe it, but it is true, nevertheless, that so

persistent, penetrating, and inter-penetrating has been the last

fortnight's rain, that in nineteen cases out of twenty a lucifer match,

"vesuvian," or fusee will obstinately refuse to ignite by any other

process than putting it into actual contact with fire, and in that case,

why, a slip of paper is just as easily dealt with, as well as more

efficacious for your purpose. Hay and corn luckily stand a good deal of

rain without being completely spoiled, but Ave are afraid to estimate

the amount of damage that another Aveek's

wet weather will cause over the "West Highlands. All our own hay and

corn has been snugly housed more than three weeks ago. Why

shouldn't everybody sow in February or early March as we

do, and have their ingathering in August, generally our best and driest

month 1 In a climate so treacherous and inconstant as ours is, it is the

greatest folly in the world to run the smallest risk that you can

possibly avoid. W| have been preaching this particular doctrine for a

dozen years past, and it has had some effect in our immediate

neighbourhood; but it is sad to see the country at large at this

moment—corn and hay rotting in the fields, that might, with ordinary

prudence and a little effort, be long ere now snug and safe under "thack

and rape."

The more one inquires the truer does he find the dictum

of a philosopher of the last century to be, that " the superstitions, as

well as the languages, of all lands and ages are linked together by

mysterious bonds, which neither time nor distance seem able to destroy."

In our immediate neighbourhood an instance of a very old superstition

was brought under our notice a few days ago, such as, with all our

knowledge of such matters, we had hitherto never dreamt of as existing

in the "Western Highlands. A man went to market at a considerable

distance to sell a good strong two-year-old colt. He did not return on

the day his wife expected him, and she became uneasy, not so much for

the well-being of her laggard liege lord and master—he had

often gone the same errand before, and had always returned safe and

sound, even if a little later than his better half had a right to

expect—but as to whether he had sold the colt, and if for anything like

the price settled between the twain as being his fair price before he

left home. She put on a large fire on her hearth, placing, when it had

reached a certain stage of ignition, a bundle of green alder boughs

atop. When the whole was fully ablaze, she went outside and watched the

direction of the smoke issuing from her chimney. The smoke was carried

in an easterly direction, a lucky quarter, and she returned to the house

and told her daughter that, whatever had come over the father— and she

threatened to tell him a hit of her mind as to his doings on his

return—the colt at least had been sold, and well sold, for the alder

smoke had gone in the hest and luckiest of all directions, towards the

east, in the direction of the rising sun; and she had never known the

omen fail. The curious thing is that within an hour or so on that very

evening the man returned, and counted into his wife's lap two pounds and

four shillings sterling over and above the expected price of the colt,

as agreed upon at home. The only other curious thing that we could

gather in "connection with the superstition is that the alder branches

must be cut specially for the occasion, and by a virgin. It was so in

this case; and we are gravely assured that, if it had been otherwise,

the ascending smoke would either have drifted hither and thither without

a purpose, unsteadily, or have uselessly intermingled with that of the

neighbouring cottages. The superstition, you must know, is a very old

one; the Greeks and Romans practised it, and from them it spread widely

over the European Continent. In books on magic and divination it is

called Capnomancy, derived,

as our friend Professor Blackie could tell you better than anybody else,

from the Greek Capnos, smoke,

and manteia, divination,

witchcraft. The ancients paid attention principally to the smoke of

sacrifices, as well as to the briskness with which the fire burned. If

the smoke ascended in a straight columnar body zenithwards, it was a

favourable omen ; if it was violently blown aside, or fell back over the

altar and the sacrificers, it was of evil augury. Our Highland dame's

notion of its taking an easterly course, towards the direction of the

breaking day, of the dawn, and the morning sun, seems to us full of a

rough and rude poetry such as you frequently meet with in carefully

examining into the details of even the grossest superstitions. Having

had occasion to be of some little service to the priestess in this rare

act of divination, we had the whole from her own lips, though she was

averse at first, as is generally the case when a clergyman is the

inquirer, to entering upon the subject at all. How these practices root

themselves among a people, defying eradication, is very extraordinary.

Did you ever, reader, crack a nut 1 Not the aristocratic

walnut or filbert over your wine, but the far superior, rich, ripe hazel

nut in its season from off the hazel bough, when the bright autumnal sun

was overhead, and the autumnal breeze stirred the leaves around you,

their multitudinous murmur resembling the far-heard music of the

restless sea. A ripe hazel nut is good anywhere, but best of all when

gathered by your own hand in its native wild wood from the overhanging

branch, whence the beautiful cluster nods at you as if soliciting your

attention, now and again, as you approach to pull it, seeming to delight

in playing a game of bo-peep with you among the leaves, like as you have

seen the Pleiades at times when, though the night be clear, many

blanket-like clouds are chasing each other in wild career athwart the

starry blue. Throughout the whole range of poetry, the hazel nut, though

often mentioned, has never perhaps had so much justice done to it as by

the Gaelic bard Duncan Ban Macintyre. In his Coire-Cheathaich, one

of his finest poems, he says :—

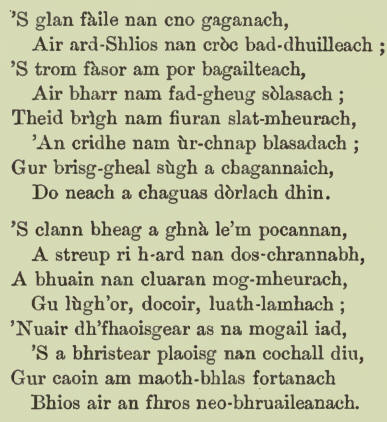

Ewen Maclachlan, commonly styled "of Aberdeen," because

he taught the Grammar School there, and there died, but who was, in

tfuth, a Lochaber man—nay, a Nether Lochaber man, born and bred, and

whose ashes rest in Killevaodain of Ardgour, without, we are ashamed to

confess it, " One gray stone to mark his grave;" he, horn, at

Tarrachalltuinn—the Height of Hazel Trees—in our parish, knew something

of hazel nuts, and thus happily describes them in their season :—

Our nuts are unusually plentiful this year, and of a size

and flavour that we do not recollect ever to have seen equalled. They

are now at that stage of ripeness when they are most delicious to the

taste, and one may indulge in any amount of them with perfect safety.

Most people are fond of nuts, hut if the reader wants to enjoy the full

flavour, to get out of a nut all that is in it, let him take the

following recipe:—" First of all, let the nut he cracked, if possible,

between your own molars,

for these are, after all, the first and most natural and best of all

nut-crackers, better quoad

hoc than

an instrument of the purest silver or steel; and there is besides,

remember, something pleasant to the palate in the feel and flavour even

of an uncracked nut. Having cracked your nut, then— and fairly placed

between the grinders, a really good nut is not difficult to crack, the

worst nuts being always the most difficult to deal with, for the more

insignificant the kernel the thicker and dourer the

shell—having cracked your nut and extracted the kernel,

whole if

possible, introduce it into your mouth, not per

se, by

itself, as is commonly done, but with a small fragment of the shell,—a

bit of pin's head size will do. Proceed now to masticate the delicious

morsel, and confess that there is a delicacy and flavour about a hazel

nut that you knew not how to extract in full, although in your day you

had cracked your bushels of them, until you were taught it from Nether

Lochaber. The philosophy of the thing is that the particle of shell

introduced with the kernel causes the act of mastication to be performed

more thoroughly than it otherwise would be, setting free the full

flavour and aroma—all, in short, that a nut has to give. |