|

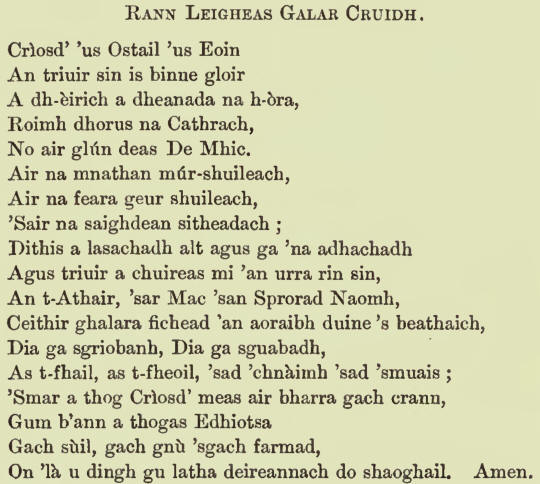

A non "Laughing" Summer—Rheumatic Pains—Old Gaelic

Incantation for Cattle Ailments.

The best

thing, perhaps, that can be said of our summer up to this date [July

1872], is that it has, upon the whole, been amiable and summer-like;

has, after the manner of a love-lorn maiden, wept much and often smiled,

although, until within the last day or two, it has never actually

laughed. You loved it, and couldn't help yourself, but your love wanted

warmth and fervour, just because of its want

of jocundity and joyousness. Even in our climate, summer is not summer

by the mere reading of the thermometer, however sensitive and delicate

its mercurial indications ; one wants brilliant sunshine, with

cloudless, or almost cloudless skies, to make up a summer as a summer

proper ought to be. The poets of the East and South always speak of

summer and summer scenes as "laughing," while in more northern and less

favoured lands your poet is content to describe otherwise exactly

similar scenes and situations as simply "smiling," "gentle," "sweet,"

"quiet," and so forth, so that an acute critic, by attending to this

alone, could tell, were other proofs entirely wanting, whether a poet

was born under northern skies, or lived and loved, soared and sang, in

sunnier and more southern climes. Horace has—

—"rmhi angulus ridet."

His " corner," observe, does not merely smile ; it " laughs "

under the bright blue Italian sky. Lucretius has—

—"tibi rident æquora ponti;"

which Creech and Dryden, hards of a colder clime, have

rendered "smiles," hut which literally and truly is honest, open, joyous "laughter "

in the southern hard. Metaetasio has—

"A te fioriscono

Gli erbosi prati;

E i flutti ridono

Nel mar placati."

"Ridono," observe—laughter

again—like his earlier countrymen, Horace and Lucretius. Our British

poets rarely venture to make spring or summer do more than smile; they

are afraid of the laughter of the south, as being quoad

hoc an

over-bold hyperbole. "We can only quote at this moment two instances in

which the laughter of more favoured lands is boldly introduced. John

Langhorne, a poet and miscellaneous writer of the last century, author

of the Fables

of Flora, very

beautifully says—

"Where Tweed's soft banks in liberal beauty lie,

And Flora laughs beneath

an azure sky."

And Chaucer, the father of English poetry, has the

following :—

"The busy larke, messager of daye,

Salueth in hire song the morwe gray;

And fyry Phebus ryseth up so brighte,

That al the orient laugheth of

the light."—

V ery

finely modernised by Dryden thus :—

"The morning lark, messenger of day,

Saluted in her song the morning grey;

And soon the sun arose with beams so bright

That all the horizon laughed to

see the joyous sight."

Our summer, then, thus far, has not been a "laughing,"

but, at the best, a merely smiling summer. There has been but little

actual sunshine, rarely such a thing as a blue, unclouded sky ; but, if

we do not err, if the wish be not altogether father to the thought, a

splendid autumn, glad and golden—summer and autumn in one, like the

companion scenes in a stereoscope, in close and kindly combination—is in

store for us. Even as it is, the country is very beautiful, and the

rains of the west, if superabundant, are at least perfectly harmless to

any one in ordinary health, no matter how often you get drenched through

and through, as the saying is, provided always you do not idly saunter

or sit down for any length of time in wet clothes; neglect this

precaution, however, and you may look out for an attack of rheumatism,

and the taste of pains to which the tortures of the rack were but a

joke—pains as fiery and intense as those threatened against the

foul-mouthed Caliban in the Tempest. You

recollect what Prospero says—

"Hag-seed hence!

Fetch us in fuel; and be quick, thou wert best

To answer other business.

Shrug'st thou, malice?

If thou neglect'st, or dost unwillingly

What I command, I'll

rack thee with old cramps;

Fill all thy bones with aches; make

thee roar

That beasts shall tremble at thy din!"

Get wet, then, as often and as much as you like, in the

"West Highlands, but don't sit down or idle about in wet clothes, is a

friend's advice; otherwise, you will soon have a pretty correct idea of

the nature of the cramps and aches of which even the brutal Caliban had

such a horror that he exclaims :—

''No, 'pray thee!—

I must obey: his art is of such power,

It would control my dam's god, Setebos,

And make a vassal of him."

Supplementary to our last paper on the spells and

incantations of the Highlands, the following has been sent to us by our

kind correspondent, Mr. Carmichael, of the Inland Revenue, Island of

Uist, a gentleman of whom highly honourable mention is made in Mr.

Campbell's West

Highland Tales,

and in some of the notes to the Rev Dr. Clerk's Ossian. Mr.

Carmichael is more conversant, perhaps, than anybody else with the

antiquities and folk-lore of the Outer Hebrides. The incantation that

follows was taken down by Mr. Carmichael from the recitation of " an

honest, unsophisticated old Banarach, or

dairymaid, in North TJist, who is even yet occasionally consulted about

sickly cows " :—

In English—

A Healing

Incantation for Diseases in Cattle.

Christ and His Apostle and John,

These three of most excellent glory,

That ascended to make supplication

Through the gateway of the city,

Fast by the right knee of God's own Son.

As regards evil-eyed women;

As regards blighting-eyed men;

As regards swift-speeding elf-arrows;

Two to strengthen and renovate the joints,

And three to back (these two) as sureties—

The Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost.

To four-and-twenty diseases are the reins of man and beast (subject);

God utterly extirpate, sweep away, and eradicate them

From out thy blood and flesh, thy bones and marrow,

And as Christ uplifted its proper foliage

To the extremities of the branches on each tree-top,

So may He uplift from off and out of thee

Each (evil) eye, each frowning look, malice and envy—

From this day forth to the world's last day. Amen.

"It is not always an easy task," writes our

correspondent, "to write from the dictation of partially deaf and

toothless old women," and we perfectly agree with him. "Ostail," in the

first line of the above spell, we take to be an insular form of Abstol, voc.— Abstoil or Abstail—the Apostle par

excellence, namely,

Paul. Mr. Carmichael appends the following elucidatory note :—"This

ora or

spell can be used for either man or beast, and is guaranteed to effect a

cure in any case ! In the case of a four-footed animal a worsted thread

is tied round the tail, and the bra or

incantation repeated. The "snathaile" (snathainn, a

thread), as this charm is called, undergoes much mysterious spitting,

handling, and incantation by the woman from whom it is got. Therann or

spell is muttered over it at the time of "consecration." Usually two

threads (da

shnathaile)

are given, and if the first is not quite successful, the second is sure

to be effectual! " |