—The

old Dog-Rhyme.

OF no

place in existence, perhaps, is the old adage, in its most literal

sense, truer than of Lochaber, that "it never rains but it pours " [June

1872], When we last wrote rain was much needed; no mid-March could be

dustier or colder than was our mid-May; rain, rain was the cry on all

hands; the birds, as they alighted on the branches or flew overhead,

cheeped it querulously; the ducks quacked it energetically; the hens

cackled and gaped for it; while the cattle afield lowed for it in a

manner the meaning of which there was no mistaking; and at last the

change of weather, so universally wished for, came—came first of all in

the shape of hail, the dira

grando of

Horace, the downright pea-size genuine article, which left the hills

around as white as if, in questionable taste, they had whitewashed

themselves for the season. Hail! fellow,

well met, was the natural and appropriate greeting. Then came sleet, a

milder form of the same visitation, not very pleasant, perhaps, but we

were grateful; then with the wind from the west, soft and pleasant as

the breath of a child, came warm, genial summer rain; the tiniest blade

of grass felt the benign influence, and, in the beautiful language of

oriental imagery, "the mountains and the hills broke forth before us

into singing, and the trees and fields clapped their hands." It is now

mild and beautiful exceedingly, with just enough of rain from time to

time to keep everything fresh and green, and at full stretch of growth,

so that crops of all kinds are everywhere making the most satisfactory

progress ; and although the unseasonable hail and intense cold of ten

days ago was very trying to the young potato plants in exposed

situations, we are glad to say that no serious damage has resulted, the

change from cold to milder weather having been very gradual. The damage

in such cases always depends on the suddenness, or the contrary, of the

transition from a low to a high temperature; a night of frost, followed

by a hot sun next day, being most dangerous to vegetable life, while

frost, followed by rain and cloud, and so on gradually to heat and

sunshine again, rarely does any more harm than merely to give a slight

check to what might otherwise prove an unhealthy rapidity of growth. In

the same way it is found that in the case of animals generally, and in

man particularly, it is not the actual and immediate amount of cold

undergone at any time that kills or maims, but the too sudden transition

from a very low temperature to a comparatively high one. It is probably

well enough known to the reader that very many of our flowers and plants

are hygrometric, some of them very sensitively so. By hygrometric we

mean that they spread out or expand their parts when the sun is bright

and the weather is dry, while they contract or close them on the

approach of moisture and cloud. We would at present draw attention to

the fact that the potato plant, in its earlier stages of growth, is very

sensitive in this respect, more so in some years than in others perhaps,

according as the plants have come up, strong and vigorous and healthy,

or the reverse; for we think our observations during many years warrant

us in saying that the more vigorous and healthier the plant, the more

sensitive will it be found to weather changes—its very sensitiveness in

this respect, observe, helping forward its growth and preserving its

vitality, by enabling it to avail itself of every favourable influence,

just as it enables it to protect itself against such influences as are

unfavourable or adverse. "We were particularly struck with this

hygrometric sensitiveness in the potato plant a day or two ago. We have

an early planted field, more forward, perhaps, than anything else of the

kind in the West Highlands, over which we took a friend who happened to

call upon us. It was about mid-day, with a bright, hot sun overhead, and

our friend agreed with us that he had never seen potatoes that had come

up more regularly, or that looked more healthy and vigorous at the same

stage of growth, the fully expanded plants already showing leaves broad

and beautiful as those of a hazel tree in June. In an hour or two

afterwards we had occasion to pass the same field, and the change in the

appearance of the plants was extraordinary. They seemed to have actually

grown a couple of inches since mid-day, and our friend exclaimed, "Well,

your potatoes are wonderful! look at them now." And we did look, not so

much, however, at the potato field as our friend did; we looked

upwards and saw that clouds were rapidly forming in the west, one black,

finger-like stripe of which had already nearly mounted to the zenith,

and looking at that and

at our potato field, we assured our friend that a heavy fall of rain,

with possibly a gale of wind, was at hand. Our companion was astonished;

the sun was yet shining brightly, and the greater part of the heavens

was clear and cloudless; but within little more than an hour afterwards

the rain fell in torrents, and a smart gale from the south-west was

blowing. Our potatoes, however, had foreseen it all; were sensible of

its approach, while our friend and ourselves thought ourselves in the

midst of fine weather that might, perhaps, last unbroken for days; and

what struck our companion as a sudden and mysterious addition to the

height of the plants was merely the effect of their having gathered

themselves together—contracted all their parts into the least possible

compass—thus assuming an upright pyramidal form, as best enabling them

to withstand the assaults of the approaching storm. Plants of less

health and vigour would, according to our theory, have shown the same

sensitiveness in the circumstances, but in a manner not so immediate,

and to a degree less marked and striking. Our companion of that day,

"who got a thorough drouking,

as we say in Scotland, on his way home that afternoon, writes us with

some humour that " as he has always had a great regard for potatoes on

the table, both mashed and 'balled,' in their 'jackets,' so in future

will he, in acknowledgment of their infallibility in the matter of

weather changes, view them with respect even in the field." It should be

stated, by the way, that this hygrometrical property in the potato plant

rapidly diminishes in sensitiveness as the haulm increases in height and

strength, as if it felt that when approaching its full growth it could

afford very much to disregard such weather changes as are incident to

the mid-summer season; but the reader who has the opportunity may verify

all we have said upon the subject for himself.

Another plant still more remarkable for hygrometric

properties is the common carline, or carlen thistle, the Carlina

vulgaris of

botanists. It is common enough in some districts of Scotland, though

those who do not know it already need not be in the least ambitious of

the honour of its acquaintance, unless indeed from a purely scientific

point of view, for the carline, wherever it appears, is almost always

the infallible sign of a poor soil, miserably farmed. The species

receives its name of Carlina from

an old story that Charlemagne introduced it into Europe on account of

some valuable medicinal qualities attributed to it; its virtues in this

respect having been revealed, it was said, to Carolus Magnus by an angel

in a vision of the night during the prevalence of a deadly plague.

Certain preparations of its roots and leaves were for centuries

afterwards held of great virtue in such internal complaints as demanded

violent purgatives for their removal; and to this day it is, we believe,

held in great repute by herbalists for the cure of vertigo, headache,

and other cerebral diseases. As a weather prognosticator, it is perhaps

unequalled hy any other British plant, the sensitiveness of its

involucral scales to the slightest weather changes being so

extraordinary as to have from very early times attracted the attention

and aroused the wonderment of those unacquainted with the fact that

similar properties, in a greater or less degree, are common to all

plants and flowers—-to the whole vegetable kingdom indeed. The carline

has a stem of some eight or ten inches in height, and bears many pretty

purple flowerets set in the midst of straw-coloured rays. The carline's

sensitiveness to weather changes continues long after it has been cut or

pulled, provided the heads have not been much hurt or bruised in the

process; on the same principle, we suppose, that some animals are known

to manifest unmistakeable signs of muscular irritability long after they

are otherwise, as we should say, to all intents and purposes dead. "We

have generally met with the carline thistle among sickly-growing oats,

on poor, thin soil, and sometimes among other luxuriant weeds in a

neglected potato field. It is amusing, by the way, sometimes to see

bonnet-badges and pictorial representations of what you are supposed to

believe is the Scottish thistle, evidently copied to the life from one

of the carline family! which are but pigmies in stature and absolutely

harmless in the matter of prickliness compared with the grand stately

fellow bristling with prickles strong as darning needles, and sharp and

venomous as the sting of a bee, with "Nemo

me impune lacessit"

in the very look of him—the true national emblem ! You remember Burns'

reference to it in a very fine stanza that has been often quoted, that

indeed everybody has by heart—

"Even then, a wish (I mind its power)—

A wish that to my latest hour

Shall strongly heave my breast—

That I for poor auld Scotland's sake

Some usofu' plan or beuk could make,

Or sing a sang at least.

The rough burr-thistle, spreading wide

Amang the bearded bear,

I turn'd the weeder-clips aside,

And

spared the symbol dear:

No nation, no station,

My envy e'er could raise;

A Scot still, but blot still,

I knew nae higher praise.'

—(Epistle to the Guidwife of Wauchopc House.)

The true Carduus

Scotticus is

not fond of cultivated land, hut is a tremendous fellow when he gets

hold of a waste outlying corner to himself, sometimes attaining a

height- of four or five, or even six feet, with a stem as thick as your

wrist, and prickles—no, spikes is

the word—with spikes, then, as formidable as the bayonets of a kilted

regiment going into action.

An anonymous lady correspondent in London sent us a

manuscript sheet of paper of the last century, containing a very old

dog-rhyme. " The paper has been in our family as long as I can remember,

and I have heard my grandfather repeat the lines often before we left

the Highlands fifty years ago. The Ronald Mac Ronald Yic John mentioned

in the rhyme was, I believe, one of the Glencoe family, a celebrated

hunter of deer in his day. He was killed, as I have heard my grandfather

relate, at the battle of Philiphaugh. It was the fairy dog-rhyme in one

of your recent letters that brought to my mind that such a thing was in

my possession." Owing to the faded state of the writing, and a very

peculiar orthography, we had some difficulty in deciphering the lines;

but, modernising the spelling a little, the following we believe to be

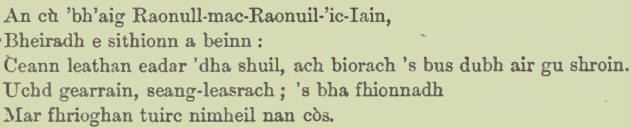

an accurate transcript:—

Which, rendered as literally as possible, many stand thus

English—

Ronald-son of Ronald-son of John's good dog,

He could bring venison from the mountain.

He was broad between the eyes; otherwise sharp and black-muzzled to the

tip of his nose.

With a horse-like chest, he was small flanked, and his pile

Was like the bristles of the den frequenting boar.

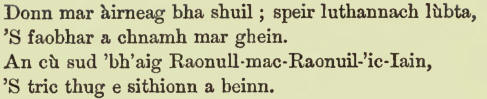

Brown as a sole was his eye;

Supple-jointed (was he), with houghs bent as a bow;

All his bones felt sharp and hard as the edge of a wedge.

Such was Ranald Mac Ranald vie John's good dog,

That often brought venison from the mountain.