|

Midges and other Bloodsuckers—The Tsetse of

South Africa—The Abyssinia — Livingstone—Adders and Grass Snakes—Lucan's Pharsalia—Celsus—Legend

of St. John ante

Portam Latmam.

Along the

west coast the weather is now [May 1872] as

mild and May-like as you could wish; the swallow twitters gaily in the

sunlight, and when he ceases his zig-zag flight for a moment to rest on

chimney-top or house-ridge, he sings a gladsome song, low and faint

indeed, and frequently lost on that account in the general chorus, but

exceedingly sweet and musical, as you will find if you give it the

attention it merits; while in the distance you hear the cheery notes of

the cuckoo, wild and startling as yet, as they burst suddenly upon the

ear from out the woodland glade or from the old rowan tree that finds

root room, you wonder how, in yonder crevice in the rock above the

foaming waterfall, hut soon to become familiar as the season advances,

and pressed upon your notice whether you will or no, and at all sorts of

impossible times and places, by the truant schoolboy's oft-repeated,

though rarely successful, attempts at imitation. For the first week in

May the temperature is unusually high, and we do not recollect ever

before having seen insect life so plentiful so early in the season.

Midges, gadflies, and other bloodsuckers are already astir in their

thousands, their taste for their favourite fluid keen and unabated, as

they fail not abundantly to manifest by an activity that one cannot help

admiring, even while wishing that it could possibly be directed to a

more legitimate and less personally annoying end. But "'tis their nature

to," as the hymn-book says, and we must grin and bear it, protecting

ourselves from their assaults as hest we may, thankful the while that

the evil is no worse. Our winged pests are innocence itself compared

with their congeners in other lands. Our midge, for instance, is to the

mosquito as the dog-fish is to the shark, as the domestic cat is to the

tiger; while our gadflies and Æstri, though

sufficiently annoying to our cattle at certain seasons, are to he

regarded as absolutely harmless if we compare them with the venomous Zimb of

Abyssinia, or the still deadlier Tsetse of

Southern Africa. The Abyssinian insect, by the way—the Zimb—is

probably the Zebub of

the Hebrew Scriptures, the estimation in which it was held from the

earliest ages being clearly enough indicated by its place in the word

Beelzebub, "the prince of devils." Livingstone's account of the Tsetse is

one of the most interesting chapters in his Travels. Shall

the intrepid explorer be restored to us? We are afraid not. It is only

too probable that, as Scott said of his protege and

friend, the author of the Scenes

of Infancy—

"A distant and a deadly shore

Has Leyden's cold remains!"

The districts of Ardgour and Sunart have always had an

unenviable notoriety for the great numbers of adders and grass snakes to

be found in them, the reptiles frequently attaining to a size unknown,

we believe, anywhere else in the West Highlands. Within the last two or

three years we have noticed that they are rapidly becoming numerous in

Lochaber, much more so than they used to be, though the general opinion,

in which we heartily concur, is that we were getting on very well

without them. During an ornithological ramble among the hills a few days

ago, we knelt to drink at a fountain that we fell in with, welling up

cool and sparkling beside a large moss-covered drift boulder among

the heather, when we were not a little startled by the presence of no

less than three adders that lay coiled together in a sort of Gordian

knot on a patch of green moss close by the fountain's brink. The day was

hot and dry, and they had probably come there to drink and bathe; but we

were very thirsty, having just smoked a pipe on the top of the hill, and

there being no appearance of water anywhere else for miles around, and

knowing, besides, that there could be really no danger, even if the

vipers had been ten times larger and more venomous than they were, we

drank a long draught of the pure sweet water, and then proceeded with

the stick in our hand to attack the enemy, and soon had the satisfaction

of knocking them into wriggling, writhing bits, and crushing their heads

under our heel. Our assault was so sudden and unexpected that they had

no time to show fight; otherwise an adder, when his blood is up and

thoroughly on his guard, is an ugly customer to attack with no better

weapon than a walking-stick, and nothing can be imagined more deadly,

wicked-looking, and savage than such an animal, as with erected crest

and flashing eye he steadies himself in act to strike. It is curious

that the poison of these reptiles, though certain death if commingled in

sufficient quantity with the blood through an abrasion or wound, is

perfectly innocuous if taken into the stomach—a fact, by the way, that

has been known from very early times. On taking our drink, for instance,

from yonder viper-guarded fountain, we recollected that Lucan had

something on a somewhat similar circumstance in his Pharsalia. Describing

Cato and his soldiers coming to a fountain of water in the desert, and

how horrified they were to find innumerable serpents of the deadliest

kind—asps and dipsades—disporting themselves in and around the pool, he

has the following fine passage, the finest indeed in the poem, which we

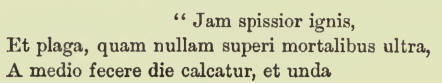

took care to turn up when we reached home :—

Which has been elegantly rendered into English as follows

:—

"And now with fiercer heat the desert glows,

And mid-day sun-darts aggravate their woes;

When, lo! a spring amid the sandy plain

Shows its clear mouth to cheer the fainting train;

But round the guarded brink in thick array,

Dire aspics roll'd their congregated way,

And thirsting in the midst the deadly dipsas lay.

Black horror seized their veins, and at the view

Back from the fount the troops recoiling flew;

When, wise above the crowd, by cares unquell'd,

Their trusted leader thus their dread dispell'd—

Let not vain terrors thus your minds enslave,

Nor dream the serpent brood can taint the wave;

Urged by the fatal fang their poison kills,

But mixes harmless with the bubbling rills.

'Dauntless he spoke, and, bending as he stood,

Drank with cool courage the suspected flood."

Celsus, an

older writer still, and styled the "Roman Hippocrates," tells us in his

great work, De

Medicina, that

the poison of serpents may be safely enough sucked by the mouth from the

wound, warning the operator, however, to be careful that the lips and

palate are free from any cut or excoriation by which the venom might

find its way into the blood, in which case it might be just as

'dangerous as if introduced into the circulation by the fang itself. It

should be stated that the grass or ringed snake spoken of above is not

in the least poisonous, though ugly enough to look at, and ready enough

to assume a threatening attitude if rudely disturbed. Nor, by the way,

is the date of the present writing inappropriate to the discussion of

such a subject, as we have at this moment discovered by the merest

accident. The 6th of May you will find is a Saint's day in the Calendar,

being dedicated to St. John ante

Portam Latinam, the

legend connected with which is as follows : —The Beloved Disciple, after

preaching the Gospel in various parts of the world, was in his old age

taken to Bome by the Emperor Domitian, and because he refused to

renounce the religion of Christ, was put into a cauldron of boiling oil

before the Latin Gate—Porta

Latina—which,

however, did him no more harm than did Nebuchadnezzar's fiery furnace to

Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego; on the contrary, John came out of the

cauldron rejuvenated, younger, fairer, and more beautiful than before.

Afterwards a cup of deadliest poison was given him to drink, but as he

was putting it to his lips, the poison, assuming the appropriate shape

of a venomous serpent, glided from the cup, leaving the draught harmless

and pure. He was finally banished to Patmos, where he wrote the

Apocalypse.

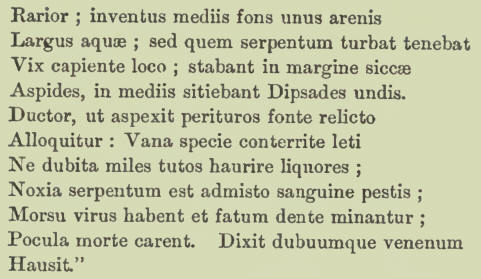

Old Fingalian rhymes and proverbs having reference to

dogs and the hunting of the stag, as it was then pursued, are very

common in the Highlands, and show how devoted to the chase were our

Celtic ancestors. Our neighbour, the Rev. Mr. Clerk of Kilmallie, in his

splendid edition of Ossian, gives

some of these old rhymes in his very interesting and learned notes on

Fingal. The

following was sent us a short time ago, and as it has never appeared in

print, we present it to the reader with a liberal translation. "We are

always glad to be able to rescue from oblivion even the smallest shred

of the folk-lore of the olden time. The story goes that this rhyme was

first of all taught by a fairy to a gay young hunter "of the period,"

under the following circumstances :—Once upon a time, a sprightly,

green-robed fairy, a sort of princess in her way, fell in love with a

young Fingalian hunter, who had frequent occasion, on his way to and

from the chase, to pass the shian or

green knoll in which the fairy hand of the glen had taken up their

abode. The fairy and her hunter lover had frequent opportunities of

meeting in secret, until some evil-disposed sister fairy divulged

Brianag's— for that was the fairy's name—imprudent and unfairy-like

conduct to the powerful fairy prince Aerlunn, who was himself over head

and ears in love with the beautiful Brianag, though she gave him no

encouragement at all; on the contrary, she flatly told him that, great

and powerful as he was, she did not love him in the least, and would

have nothing to do with him. On hearing how things were going on,

Aerlunn was very jealous and very angry, just as a mortal might be under

similar circumstances, and he issued an edict, as Prince of the Fairies

of that glen, by which, after reflecting severely on the unfairy-like

conduct of Brianag and others of the band, he prohibited Brianag from

leaving the shian on

any pretence whatever, except for the one hour before midnight on the

night when the moon completed her first quarter—perfect liberty to do as

they like during this one hour in the month is every fairy's birthright,

and no power can deprive them of it. He would have done something very

dreadful to Brianag's lover, only the latter was protected from any evil

a fairy enemy could do to him by a talisman of extraordinary value,

which his uncle, a priest of the Druids, had given him, and which he

always carried on his person. Brianag and her lover were thus able to

meet for one hour in every month, despite the opposition of the angry

Aerlunn, whose jealousy became at last so insupportable, that he

resolved to shift his court and people from that glen to another at a

great distance. To this arrangement, much as she regretted it, as it

separated herself and her lover, Brianag dare not object. It is a

prerogative appertaining to the Princes of Fairyland that they can shift

their court at will, when and whither they please. The fairy palace thus

forsaken is still to be seen in Glen Etive, and has ever since been

called An

Sithean Samhach—the

Quiet or Deserted Eairy Knoll. On parting with her lover at their last

interview, Brianag presented him with a silver horn, whose blast could

be heard, loud and clear, over the Seven Hills and across the Seven

Glens ; and knowing that it was his ambition to excel all others in the

chase, she instructed him as to the best kind of dog to have and hunt

withal as follows :—

Which may stand in English thus :—

Get a yellow brindled dog,

First-born of his dam's first litter,

With a muzzle black as jet,

Reared on whey and milk of goats;

No stag in forest can escape him.

Those who rear deer-hounds, et

juvenes qui gaudent canibus, might

do worse than experiment a little according to the fairy's receipt; we

shouldn't wonder at all if a splendid dog was the result, for these old

rhymes are rarely devoid of reason. There is no reason at all events why

such a dog might not turn

out well. |