|

The Vernal Equinox—Beauty of Loch Leven—Astronomical

Notes—How an old Woman supposed to possess the Evil Eye escaped a cruel

death.

The vernal

equinox has come and gone, unaccompanied this year [April 1872], as it

was unheralded and unannounced, hy anything like the storms that from

the earliest times have been observed to be attendant on the sun's

crossing the equator. It is by no means certain, however, that these

storms may not even now be a-brewing, to make themselves yet felt in all

their fierceness, for we have noticed in recent years particularly that

what are called the " equinoctial gales" quite as frequently follow, as

accompany or precede, the exact equality of day and night. We have just

had a fortnight of genuine -March weather—clear, cold days, and frosty

nights—the air snell and biting, to be sure, and keen of edge, as might

be expected on the uplands; but in places sheltered from the east and

north it is delightfully bright and sunny, the incessant song of birds,

the hum of wild bees, and the gay fluttering of early butterflies,

making one think of Whitsuntide rather than All Fools' Day; the

twittering of swallows and the cheery notes of the cuckoo alone are

wanting to make the illusion perfect, and these, unless the weather

should undergo some extraordinary and unexpected change, must certainly

soon be heard, much earlier this year, we should think, than usual. We

are particularly favoured in this respect along the northern shores of

Loch Leven. Here, to quote Burns—

''Simmer first unfaulds her robe, and here the langest

tarry;"

and as we wander afield we often apply the words of

Horace to our own little spot, as from some neighbouring height we view

it cozily nestling in the sunlight—

Ille terrarum mihi prater omnes

Angulus ridit;

which may be rendered—

What e'er the beauties others boast,

This spot of ground delights me most.

Or, as we prefer putting it in our own case—

Of brighter skies and sunnier climes let others boast and

jabber,

Give me the sunny, southern shores of mountain-girt Lochaber!

Or yet again, if you will have it still more literally in

Gaelic—

'S anns' leam na spot eil' fo 'a ghrein,

M' oisinneag bheag, ghrianach fein.

During the present clear, cold spring nights the starry

heavens are very beautiful. Jupiter, just below Castor and Pollux, is at

his brightest, and very favourably situated for observation, his cloudy

belts and bright diamond-point-like satellites being visible in an

instrument of very moderate powers. If between nine and ten o'clock the

reader will turn to the north-east, he will find a constellation pretty

high up in the heavens, and consisting of five or six principal stars,

none of them, however, of the first magnitude, opening towards the pole

star in the form of a widely spread-out This constellation will be an

object of more than usual interest during the present year. It is Cassiopeia, or The

Lady in her Chair, the

scene of a very startling and strange phenomenon in 1572, which, it has

been asserted with some confidence, is not at all unlikely to be

repeated in 1872. In 1572 a new star of great splendour appeared in

Cassiopeia, occupying a place that had hitherto been blank. It was first

observed on the 6th August, by Schuler, of Wittemburg, shortly after

which it arrested the attention of the celebrated Danish astronomer

Tycho Brahe, who watched its rapid increase of brilliancy night after

night with the liveliest interest. Its magnitude at last rivalled, if it

did not even exceed, that of Jupiter, with an effulgence equally bright

and vivid. After shining with great splendour some time, and attracting

the earnest gaze of the most distinguished astromomers of the period,

its brilliancy began steadily to decline, changing its colour in a very

remarkable manner as it became fainter and fainter, until finally it

became invisible in March 1574, and has never been seen since. Sir John

Herschel and other astronomers have suggested that its reappearance in

1872 is by no means an improbable event; and towards no constellation in

the northern heavens, in consequence, will the observer's eye be so

constantly turned throughout the present year as to Cassiopeia. The

reappearance of such a star would be certain to give rise to the most

startling theories. With the spectroscope in our possession, however,

and the marvellous telescopic power at our command now-a-days, we could

not fail to arrive at more intimate terms with such a stranger than was

i possible in the days of Tycho Brahe. The interest and excitement in

the astronomical world in connection with the sudden burst of splendour

in the star in Corona a

year or two ago was very great, but would be still greater in the event

of the reappearance of the long absent stranger in Cassiopeia. In the

one case it was only a remarkable increase of light and lustre in the

star already existent and visible; but the reappearance of a new orb in

a spot blank and starless in the most powerful telescopes for three

hundred years, would be almost equal to the sudden creation of a new

sun. Here, by the way, good reader, if you are ambitious, is a chance

for fame. Be but the first to detect the reappearance of this remarkable

star-stranger, and your immortality into all time shall be more secure

than if you wrote an epic to rival the Iliad, or

a tragedy equal to Hamlet or Othello. The

name and memory of George Palitch, the amateur peasant astronomer, who

was so fortunate as to obtain the earliest glimpse of Halley's Comet on

its first return to perihelion after its periodicity had been so boldly,

and as some thought so rashly asserted, is more secure in that

connection than if, either as king or conqueror, he had all the honours

of the most imperishable brass or marble.

A hundred years ago or more, when Highlanders were more

superstitious than they are now, or when, to be more correct, they took

less pains to conceal their superstitious beliefs than at the present

day, a certain hamlet in a remote part of the country was sadly troubled

by an " evil eye," whose unhallowed powers wrought "mickle woe," to the

manifest loss and discomfort of the good people around. The cows no

longer yielded their lacteal treasures in the desired abundance, nor did

the calves grow and thrive, as calves in good keeping should. Churns,

however shaken and jolted, refused to turn out their hebdomadal pot of

butter; or if, after much weary labour, they did reluctantly yield any,

it was found to be pale and rancid as unsalted suet in the dog-days.

Stirks and other young " beasts," though the rents depended on them,

sickened and dwined and died, without apparent reason ; and even

children, hitherto in rude and ruddy health enough, were frequently

prostrated by sudden and unaccountable illnesses. That an "evil eye" of

more than ordinary virulence and power was at work was at last conceded

even by the most sceptical as to such influences, and suspicion

straightway fell upon a lone old woman, who lived in a hut on the

outskirts of the township. Originally a stranger to the district, and of

a taciturn and retiring disposition, she had long been looked upon with

suspicion and dislike, and now a number of young men resolved to be

revenged on her as the secret author of all that was amiss in the

hamlet. At a late hour one dark night they proceeded to the poor old

woman's hut, with the intention of setting fire to the roof and burning

it about her ears, not caring very much either even if the "evil-eyed

witch" herself, as they called her, should be buried under the burning

rafters of her cottage. As the young men noiselessly surrounded the hut,

they found that the old woman was just about retiring for the night, and

as some of them stood at her window, and looked and listened, they could

see her, by the light of a bog pine fire, kneel at her bedside, and

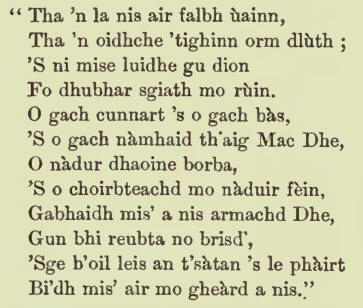

after a little they heard her repeat the following prayer :—

Which, literally rendered into English, will read thus:—

"The day has now departed from us;

Dark night gathers around,

And I will lay me safely down (to sleep)

Under shadow of my Beloved One's wing.

Against all dangers, and death in every form,

Against each enemy of God's good Son,

Against the anger of the turbulent people,

And against the corruption of my own nature,

I will take unto me the armour of God—

That shall protect me from all assaults:

And in spite of Satan and all his following,

I shall be well and surely guarded."

The old woman's confidence in the Divine protection was

not misplaced; the heart of youth is generous, and the beauty and

solemnity of the scene carried it captive. The young men felt that one

who could thus, on retiring to rest, commend herself to God and God's

Son, could not be the "evil" old woman they had thought her. Awed and

impressed, silently and on tip-toe, they departed for their homes,

leaving the old woman in peace. By-and-by things went well again with

the cattle of the hamlet, sickness disappeared from the district, and

the old woman continued to live the same quiet, unobtrusive life a few

years longer, and was as much respected and loved latterly, the story

says, as she was at one time hated and feared. Nor did she ever know of

the young men's midnight visit to her hut on an errand so happily

frustrated.

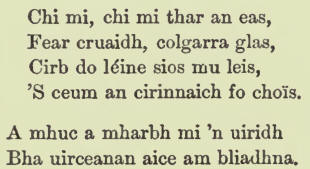

The following are a couple of very excellent "toimhseachan" that

were sent us a few days ago. Finding the correct solutions will afford

some amusement to our Gaelic readers during the first idle half-hour—

|