|

Storms—An "inch" of Rain—Atfwrina

Presbyter—Lophius Piscaiarius —Mr.

Mortimer Collins' misquotation from the Times.

A finer winter

[January 1871] never

was known all over the West Highlands and Hebrides. Some tempestuousness

is to be looked for at this season, and some tempestuousness we have

had, but of actual winter rigour and cold we have hardly had a trace.

Only twice during the winter have we had any frost, and even then it was

but slight and of short duration. On several occasions, however, we have

had such terrible rainfalls as are only known perhaps within sight of

the mountain peaks of Jura and Mull and Morven. On the 19th of January,

and again on the 23d, the rainfall within a given time was heavier than

anything known even with us for many years past. In about sixteen hours

on the 19th, 4.19 inches fell, and quite as much, if not more, on the

23d. Now, does the reader know what an inch of rain means? It means a

gallon of water spread evenly over a surface of something like two

square feet, or, to put it in a more striking and intelligible form, it

means a fall of a hundred

tons upon

an acre of land ; so that in sixteen hours on the 19th upwards of four

hundred tons

of rain fell on every acre of land for miles and miles around us. It

will be confessed that thus the country was for once at least well

soaked and saturated. All our rivers and mountain torrents were, of

course, in full flood, and throughout the night, when it had calmed down

a little, the "noise of many waters," as you lay awake on your pillow

and listened, made wild and eerie music enough, to which the fitting

bass was the boom of the storm-driven rollers as they broke in sullen

thunder along the shore. We had occasion to be across Corran Ferry on

the wettest of these days, bad as it was, and, in spite of waterproofs

and haps of most approved texture and form, we returned in the evening

so soaked and drenched and droulrit, to

use an expressive Scotticism, that we might as well have been for half

an hour up to our chin, over head and ears for that matter of it, in the

deepest pool of the Rhi. "When changing our clothes in our own room

after getting home, we managed to raise a quiet laugh with ourselves

over it all, by the recollection of the music and words of a favourite

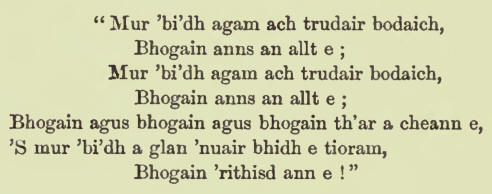

Scotch reel not altogether inapplicable to our then condition. The reel

in question is a well-known one, though we forget at present its proper

distinctive name. It is, Ave think, one of Neil Gow's. A gudewife,

presumably of Amazonian heart, and also of Amazonian proportions, makes

her husband Avince and

quail, and conduct himself with becoming amiability and decorum, as she

sings—

Not very easily turned into English, but this is

something like it—

"If my gudeman were cross and dour,

I'd dip him in the burn, O!

If my gudeman were cross and sour,

I'd dip him in the burn, O;

I'd dip the dear o'er head and ears until he'd grane and girn, O,

And till he promised better things, he'd get the tother turn, O."

While stripping, it struck us that we were quite

as wet on

the occasion in question, as if for our sins we had

undergone all the

"dipping" threatened by the gudewife in the old reel •

and the idea put us into good humour until tea and other fireside

comforts made us forget all the pelting of the pitiless storm. How the

remainder of winter and early spring may turn out meteorologically, it

is impossible to forecast with any confidence, but meantime our old

people, in their own opinion, at least, weatherwise and shrewd quoad

hoc, are

gravely shaking their heads over what they deem an unusual dearth of

frost and snow in mid-winter.

Our West Coast storms, if in one sense sometimes

disagreeable enough, rarely fail, however, to bring us a good thing in

the shape of hundreds of tons of drift-ware, which, gathered and spread

on the land, is found to be a valuable fertiliser. It is a labour,

besides, which falls to be done in a season when there is little else to

occupy the people's time, and saves an immense deal of trouble when the

spring comes round, for the land is ready for the plough and the

immediate reception of the seed, whatever the crop—thus saving at once

the manure heap for purposes in which farmyard manure is indispensable,

and all the trouble of long cartage afield. In collecting his share of a

huge swathe of this drift-ware the other day, one of our neighbours

found a dead fish, quite fresh and unmutilated, which being new to him,

though a fisherman and sea-shore man all his life, he thought might be

interesting to us. He accordingly brought it to us, and to us also it

was new, and as such, of course, exceedingly interesting. We puzzled

long over it ere we satisfied ourselves that we had determined its

identity. It was a small fish, some six inches in length, and of

smelt-like shape and form and colouring, but it was not a smelt. After

some little trouble, we finally decided that it was a species of

atherine (Atherina)

belonging to the Mugilidce or

mullet family. Out particular specimen was the Atherina

presbyter, a

not uncommon visitor on some of the south of England shores, but so rare

in our seas that, as we have already said, we never saw a specimen

before. We are told that the atherine is very good eating, and we can

quite believe it, for it is a pretty, delicate-looking little fish,

that, nicely fried until properly crimp and brown, ought to taste well.

A much commoner fish, but interesting in this instance for the great

size of the specimen, was an angler, fishing-frog, or sea-devil (Lopliius

piscatorius), which

was cast ashore near Corran Ferry last week. This was the largest

individual of the species—the ugliest, perhaps, of all fishes—that we

ever saw. It measured five feet seven inches from snout to tip of tail,

and weighed fifty-three pounds. It was poor and fleshless, and had died

seemingly of sheer inanition or atrophy; had it been in full condition,

it would have weighed a third more. Its terrible mouth, with its

formidable array of sharp recurved teeth, was enough to scare a friend

that accompanied us to a distance, though we assured him that the brute

was dead and harmless. On opening out its jaws to a fair extent—that is,

as far as we thought the animal itself would open them easily if need

were, we placed a large turnip from a pit that was conveniently at hand,

a turnip nearly as large as a man's head, easily within the horrid

cavern. We would willingly have taken this specimen home with us, for

the purpose of preserving the skeleton, but we had no conveyance with

us, and any idea of carrying it Avas out

of the question. It had, besides, evidently lain some time on the beach,

and its odour on moving it in the least Avas, the

reader may believe, the very antipodes of Eau de Cologne or ottar of

roses. We contented ourselves therefore with slitting open its stomach

with our pocket-knife, and found it, as Ave expected,

perfectly empty, containing nothing in the shape of food, except the

tips of tAvo

claAvs and

small bits of the carapace of a not uncommon species of crab, the velvet

fiddler (Portunas

puber). The

Highlanders of the west coast and Hebrides call the angler Mac

Lamhaich, properly Mac

Lathaich—the

son (that is, inhabitant) of

the mud or ooze; a very expressive and appropriate name for it, for it

is essentially a

mud fish,

in which, half buried and perdu, it

hides and watches, tiger-like, for its prey. The naturalist meets with

many things to puzzle him, and it has always puzzled us to account for

the large size of this animal's head and mouth, altogether

disproportioned to the size of the rest of the body. No matter how

insatiable the cravings of the brute's maw—to use a Miltonic word—no

matter how gluttonous soever of appetite, the head and mouth, and number

and size of teeth, do seem unnecessarily formidable, monstrous indeed,

for any conceivable work that they can be called upon to perform; and

yet there is unquestionably good reason for it all, if we could only

find it out. It may interest some of our readers to know that the

sea-devil belongs, ichtbyologically, to the Acanthopterygious family of

fishes. A

canthopterygious! what

a staggerer to any one except a learned ichthyologist at a Spelling Bee.

Mr. Mortimer Collins and others are recently down,

somewhat hypercritically we can't help thinking, on Mr. Tennyson's

occasional natural history references throughout his poems. The fun is

that in almost every instance in which fault is found with him, Mr.

Tennyson is right and his critics wrong ! Here is one example of this

hypercriticism in which Mr. Mortimer Collins is fairly hoist with his

own petard. Mr. Tennyson writes—

"In spring a fuller crimson comes upon the robin's

breast."

Upon which Mr. Collins comments—"As a fact, that fuller

crimson comes in autumn, as all know who watch the half-shy,

half-familiar bird—

"That ever in the haunch of winter sings."

Here Mr. Mortimer Collins is partly right and largely

wrong, while Mr. Tennyson is altogether right. It is true that our

native song-birds, moulting in autumn or early winter, assume at this

season a thicker, warmer, fresher plumage after all the wear and tear

consequent on the labours of nidification, incubation, and love-making

throughout the spring and summer; but it is equally true that it is only

in spring, as Mr. Tennyson correctly asserts, that our wild birds assume

their gaudiest and gayest attire, every colour and shade of colour in

the individual bird's feathering there and then only being at its best

and brightest. And when we remember that spring is the season of love

and incipient song, we should be very much surprised, and with good

reason, if the fact were otherwise. So far as our recollection serves

us, Mr. Mortimer Collins, or any one else, will find it rather difficult

to catch Mr. Tennyson tripping in the direction indicated. "We should

say that the Poet Laureate was rather remarkable than otherwise for his

fidelity to nature and truth in all his local colouring.

Some time ago, by the way, we had occasion to call

attention to the exceeding frequency of misquotation in our current

literature, and in quarters, too, where one would least expect it. Here

is a curious and very unpardonable instance, all things considered. In a

review of the South

Kensington Handbooks, in

the Times of

the 18th January, a sentence opens thus—"It is well-known that weary lies

the head that wears a crown?" Every one will see that the manifest

intention here is to quote from the monologue of the poor harassed and

sleepless King in Shakespeare's Henry IV. (part second), one of the

finest things that even Shakespeare ever wrote, and we had thought too

well-known by every one with any pretensions to literature to be

misquoted. The concluding lines are these:—

"Can'st thou, O partial sleep, give thy repose

To the wet sea-boy in an hour so rude;

And in the calmest and most stillest night,

With all appliances and means to boot,

Deny it to a king? Then, happy, low, lie down:

Uneasy lies

the head that wears a crown." |