Charles

the First and Lord Falkland—Virgilius the Magician—Thomas of Ercildoune.

With occasional

gales of wind and blustering showers [October 1868], that, from their

chilliness and snellness, you

suspect to be sleet, although you don't like as yet exactly to say

so—meteorological phenomena, however, in no way strange or unusual on

the back of the autumnal equinox—the weather with us here continues

delightfully bright and breezy, and the country looks beautiful. Field

and upland are still as freshly green as at midsummer, while the deep,

rich russet hues and golden tints of the declining year, gleaming in the

fitful sunlight, and intermingling their glories with the still

beautifully fresh and unspotted foliage of our hardier trees and shrubs;

with the ripe, ruddy bloom of the heather empurpling the moorland and

the hill, and a perfect sea of "brackens brown" mantling the mountain

side, and fringing, in loving companionship with the birch, the alder,

and the hazel, the torrent's brink, as it leaps in foam from rock to

rock and dashes downwards with its wild music to the sea,—all this, with

a thousand indescribable accessories, scarcely perceptible indeed in the

general effect, but all bearing their fitting part in the delightful

whole, presents at this season, and never more markedly than this year,

a scene that you never tire of gazing at, and declaring again and again,

and with all your heart, to be "beautiful exceedingly." As you gaze on

such a scene as this, you feel that no painter could paint it; that

there is a something in it all too subtile and spiritual to be

transferred to canvas by any art whatever. An imitation, indeed, of all

that is palpable and tangible about it you may get, and it may be very

beautiful perhaps, and a triumph of art in a way; but, even as you gaze

in admiration, ready to grant the artist all the praise that is his due,

are you not apt, remembering the scene as nature has it, to

"Start, for soul is

wanting there?"

But we must not be misunderstood. Painters and painting

we love, and have always loved, and should be sorry, indeed, to be

considered as in any way dead or indifferent to the power and beauty of

the art. Painting, after all, however, and especially landscape

painting, is but an imitative art,

and the longer we live, and the more we are brought face to face with

nature, the more shall we feel that there is a charm, an attractiveness,

and a loveliness about her all her own—a something that

you feel but cannot describe, that the artist as he gazes feels too, and

strives to grasp and instil into his picture, but cannot charm into

interminglement with his colours, "charm he never so wisely." Viewed

aesthetically, nature in sooth consists not of matter only, but of

matter and spirit, and

therein is the secret of her surpassing power over us. You may subtly

imitate and reproduce exact representations of her more prominent

features and general outlines, and the painter, according as he is more

or less gifted with the poetic mens

divina, may

infuse a moral meaning into

his work, and a subtile beauty entirely independent of the mere

manipulation of his subject—be it landscape, seascape, or cloudscape—and

his work may impart instruction as well as pleasure and delight; but,

granting all this, there shall still be something awanting even in the

finest pictures, that something which we have ventured to call

spirit—the spirit that pervades and permeales nature in all her works,

that is her life, that may be "spiritually discerned" in

her, but

cannot be transferred to canvas.

In the collection of Jewish traditions known as the Talmud there

is a very pretty story of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, that will

serve to illustrate our meaning better than the longest dissertation

could be. It is to the following effect:—Attracted by his wealth, and

wisdom, and power—the fame whereof had gone forth into all lands—the

Queen of Sheba, the Beautiful, paid a visit to Solomon, the Wise, at his

own court, that she might there admire the splendour of his throne and

be instructed of his wisdom. Charmed with the courtesy and gallantry of

the accomplished King, delighted with the magnificence and splendour of

his court, and amazed at his surpassing wisdom, which, indeed, exceeded

all that she had heard reported of it, the Queen still thought that

Solomon could be outwitted, and she resolved to have the glory of

puzzling and outwitting one so wise. To this end she one day presented

herself before the King, bearing in one of her hands a wreath of natural

flowers, the most beautiful she could gather, and in the other a similar

wreath of artificial flowers, the most beautiful and like unto natural

flowers that the cunning of herself and her handmaidens could fashion.

Of the two wreaths the hues were of the brightest, and the flowers of

the one wreath were as if they had been pulled off the same stalks that

bore the flowers of the other. "Tell me now, O King," said the Queen as

she stood at some distance from the throne whereon the monarch sate,

"Tell me now, O King, which of these wreaths I hold in my hands is

fashioned of artiticial flowers, for one of them is so fashioned; and

which of them of natural flowers, that grew from out the earth, and

imbibed their beauty and their brightness from the sun, for of such of a

truth is one of them formed 1" And, lo, the King was perplexed and

sorely troubled, for he wist not what answer to make, seeing that the

two wreaths were as like one to another as twin sisters at their

mother's breast, or twin lilies on the same stalk. And the courtiers of

the King, and his princes, and his servants, were sorely grieved that

the sagacity of the King should be at fault, and his superhuman wisdom

at last fail. But, lo, the spirit of wisdom came upon the King in his

perplexity. Observing some bees clustering outside, he ordered the

window to be opened, and soon the bees came swarming into the court, and

after hovering for a moment about the one wreath, they straightway left

it and settled upon the other, which observing, "That," said

the King, "that, and

not the other, is the wreath of the flowers that grew from out the earth

and in the sun, and were not fashioned with hands." And the Queen was

mightily surprised at the exceeding wisdom of the King, and did

obeisance unto Solomon, laying the wreaths of flowers upon the steps of

the ivory throne that was overlaid with gold, and of which there was not

the like made in any kingdom. And the courtiers, and the princes, and

the servants of the King clapped their hands and cried, " 0 King! live

for ever." If we are wise and judge aright, we shall always, like the

bees of Solomon, be attracted by nature rather than by art, however

beautiful. Our doctrine was never, perhaps, so briefly and pithily

enforced as by the Macedonian conqueror on a certain occasion. A

courtier one day asked him to listen to him how well he could,

whistling, imitate the notes of the nightingale. Alexander declined the

proffered musical entertainment with the contemptuous remark, "I

have heard the nightingale herself." In

wonder that the would-be melodist slunk away abashed; and such be the

fate of all mere echoers and imitators when at any time they claim more

than is their due, or would have us appraise their pinchbeck at the

value of sterling gold. There is an amount of truth, and a hidden

meaning and beauty, in Byron's lines, that he was himself perhaps

unconscious of in the ribald mood of the moment, when, alluding to the

statuary's art, he exclaimed—

"I've seen much finer women, ripe and real,

Than all the nonsense of their stone ideal."

It is astonishing how difficult of thorough eradication

are certain superstitions, if once established amongst a people. Once

let the popular mind become inoculated with error in this shape, and

although times may change and the manners of the people may alter,

though a new tongue even shall have succeeded the language in which the

error was imbibed, and knowledge have spread and civilisation have

steadily progressed, yet there the superstition still lurks, frightened

it may be at the outward light, and, owl-like, ashamed to appear in the

brightness of the blessed sunshine of unclouded truth, but ever ready,

nevertheless, under favourable circumstances, to manifest itself, and

assert its sway over its votaries, like certain fabled mediaeval

philters and potions that when administered are said to have lurked for

years and years in the human system, till, under certain conditions,

their subtle properties were called into active operation, and the

desired effect was produced. A short time ago we spent an evening in the

company of a gentleman from the south of Scotland, a distinguished

antiquary and archaeologist, and of wonderful skill in everything

connected with the folk-lore of

Scotland, whether of the past or present. In the course of conversation,

" over the walnuts and the wine," our friend surprised us not a little

by informing us that even at this day, in certain parts of the

south-western districts of Scotland, the Sortes

Sacrce are

frequently resorted to by the people when they are in doubt or

perplexity about anything of sufficient importance in their opinion to

warrant their having recourse to this ancient mode of divination. The Sortes

Sacrce are

founded upon the more ancient Sortes

Virgiliance—Virgilian

Lots, a method of divination which had at least the merit of being

extremely simple, and not necessarily occupying much of the votary's

time. What may be called the literary oracle, as distinguished from

vocal oracles, was consulted in this wise: The operator having before

him a copy of Virgil—thesortes were

generally confined to the

AEneid—opened

the volume ad

aperturam lihti, anywhere,

at random, when the first passage that accidentally struck the eye was

carefully read and pondered with as little reference as possible to its

immediate context, and a meaning extracted from it which was supposed to

indicate the issue of the event in hand, and which was to be considered

inevitable and irrevocable as the fates had so decreed. A man with the

knowledge thus obtained could not by any precaution or change of conduct

avert the impending doom, good or evil; he could only put his house in

order, and so arrange matters the best way he could; that if evil came

it might be borne with dignity and patience; if good, that it might be

enjoyed with moderation and devout gratitude to the gods. It is said

that at the outbreak of the troubles that culminated in the

Commonwealth, Charles I. and Lord Falkland found themselves on a certain

day in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, when the latter jocularly

proposed that they should inform themselves of their future fortunes by

means of the Sortes

Virgiliance; and

certainly, read by the light of after events, it must be confessed that

the passages stumbled upon seem singularly ominous of the fate that

overtook both. The passage read by the Martyr King was from the fourth

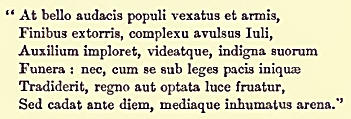

book of the AEneid, and is as follows :—

Which Dryden, if with rather too much amplification,

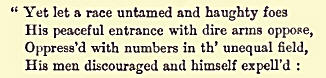

still very beautifully translates thus :—

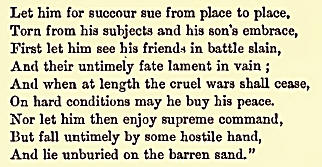

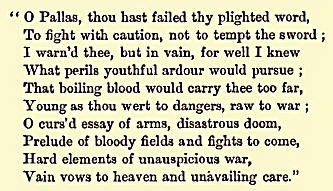

Lord Falkland's eye fell on the following lines in the

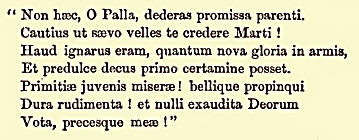

eleventh book:—

—which the same translator has rendered as follows :—

How the most pious man of his age, and one of the best

kings that ever adorned a. throne, suffered death at the hands of his

rebellious subjects is well known. Poor Lord Falkland—a young nobleman

of the most estimable character ; a poet and man of letters, so fond of

books that he used to say that " he pitied unlearned gentlemen in a

rainy day "—fell gallantly fighting for the royal cause in the battle of

Newbury, before he had yet completed his thirty-fourth year. It is

curious to find the eminent poet Abraham Cowley, a good man too—of whom

at his death Charles II. was heard to say that " Mr. Cowley had not left

a better man behind in England," —it is curious, we say, to find him on

a certain occasion seriously referring to the Virgilian

Lots,

and, what is more, avowing his firm belief in them ! During the

Commonwealth, Cowley was in Paris, where he acted as secretary to the

Earl of St. Albans (then Lord Jermyn), and had a good deal to do with

the negotiations that eventually led to the Restoration. In one of his

letters, speaking of the Scotch treaty then in agitation, he

says—seriously, observe, and in an official document—"The Scotch treaty

is the only thing now in which we are vitally concerned. I am one of the

last hopers, and yet cannot now abstain from believing that an agreement

will be made ; all people upon the place incline to that union. The

Scotch will moderate something of the rigour of their demands; the

mutual necessity of an accord is visible, the king is persuaded of it. And,

to tell you the truth (which I take to be an argument above all the

rest), Virgil has told the same thing to that purpose." He

had evidently consulted the Virgilian

Lots, and

a passage presenting itself that could somehow be twisted so as to point

to a favourable issue to the Scotch business in hand, he accepts the

oracle, and in all seriousness announces his belief in it ! "When we

find a man of refinement and culture and high moral character like

Cowley crediting such nonsense, can we much wonder at the lengths to

which fanaticism and superstition carried people in those unhappy times?

To understand why Virgil, of all the ancient poets, Roman or Greek, was

selected as the oracle in this mode of divination, we must remember that

the Mantuan bard had the credit amongst his countrymen of having been a

sorcerer or necromancer and prophet as well as a poet, something like

the British Merlin, or

our own Thomas

the Rhymer and Michael

Scott, only

more famous, perhaps. Would the reader suppose, for example, that the

theory of volcanic action is all a myth, and that it is to the magic of

Virgil, and to nothing else, that the south of Italy is indebted for all

the earthquakes and subterranean convulsions that have afflicted it for

centuries 1 Yet so it is, if wo are to credit all the stories of "

Virgilius the Magician " that were current during the Middle Ages. The

celebrated Benedictine monk, Bernard

de Montfaucon,

author of Antiquite

Expliqufe one

of the most learned and curious works in existence, repeats the story as

it was told and credited in the Dark Ages. The following is from an old

translation, quoted by Scott in his notes to the Lay

of the Last

Minstrel,

in illustration of the magical spells attributed to the Ladye of

Branksome Tower. Virgil it seems, among other things, was famous for his

gallantries. On one occasion he fell in love with and carried away the

daughter of a certain "Soldan," and the story proceeds:—"Than he

thoughte in his mynde how he myghie marye hyr, and thoughte in his mynde

to founde in the middes of the see a fayer towne, with great landes

belongynge to it and so he did by his cunnynge, and called it Napells

(Naples). And the foundacyon of it was of egges, and in that town of

ISTapells he made a tower with iiii. corners, and in the toppe he set an

apell upon an yron yarde, and no man culde pull away that apell without

he brake it; and thoroughe that yren set he a bolte, and in that bolte

set he an egge, and he henge the apell by the stauke upon a cheyne, and

so hangeth it still. And when the egge styrreth so should the town of

iSTapells quake; and when the egge brake, then shulde the town sinke.

When he made an ende, he lette calls it Kapells." Thomas of "Ercildoune,"

and he of "Balivearie," and the two Merlins,—for

there were two of them, the Merlin of the Arthurian legends, and Merdwynn

Wylet, or

Merlin the Wild, who seems to have been a Scotchman, and whose grave is

still pointed out beneath an aged thorn-tree at Drumelzier in Tweeddale,—these

were accounted great magicians and "pretty fellows in their day;" but

what were they to Virgilius the earthquaker, who at least attained to

such an enviable state of independence, that he is represented as

frequently playing at pitch and toss with the "devyl," and cheating and

outwitting that crafty potentate as if he were the veriest greenhorn!

The Sortes

Sacrce were

just the Sortes

Virgiliance, with

this difference, that in the former case, instead of a copy of Virgil,

the New Testament was used in the process of divination. The oracle is

consulted in this case, according to our information, by the

introduction at random of the wards end of a key (some allusion probably

to the Apostolic keys) between the leaves of the closed volume, which is

then opened at that place, and from the first verse that arrests the eye

the desired knowledge is extracted. On inquiry, we find that this

superstition was still occasionally practised in the Highlands of

Scotland some fifty years ago, though we would fain hope and believe

that it is now unknown. It is curious that it should still be frequently

resorted to in the south-western districts. It seems to have been a very

general as well as a very ancient mode of divination. Hoffman, in his Lexicon

Universale, tyc., informs

us that it was practised by the Jewish Rabbins with their sacred books,

as well as by the Pagans from very early times, and was common amongst

the Christians of the Middle Ages. We are informed by a gentleman, wrho

spent many years in the East, that the Mahometans frequently resort to

this method of divination, taking the Koran as their oracle.