|

Herrings—Chimara

Munstrosa— Cure

for Ringworm—Cold Tea Leaves for inflamed and blood-shot Eyes—An old

Incantation for the cure of Sore Eyes—A curious Dirk Sheath— A Tannery

of Human Skins.

However unproductive

the herring fishing season may he quoad herrings,

and this has so far been the worst of a series of bad seasons [September

1870], it rarely fails to provide more or less grist for our mill in the

shape of some rarity in marine life worth chronicling. A very ugly and

repulsive-looking fish, extremely rare too, was sent us recently for

identification. It was caught in Sallachan Ely, in our neighbourhood,

having become entangled in the comer of a drift net which the fishermen

were hauling into their boat in the grey morning, after a long,

wearisome, and profitless night's labours. "We had seen the fish before,

though not often, and had therefore no hesitation in recognising it as

the Chimcrra

monstrosa—a

scientific name, by the way in which its lack of beauty is plainly

enough indicated— a cartilaginous fish, two feet in length, and of

somewhat elongated and hake-like form. The general colour is a dull

leaden white, mottled on the under parts with small spots of rusty

brown. On examining the contents of the stomach, they were found to

consist of some very small herring fry, along with partly digested

fragments of the adult fish, whence it may be concluded that the Chimcera's favourite

prey, when they can be had, is herring; a conclusion at which we might

also easily arrive from the fact that it is seldom or never met with on

our shores, except when herring are more or less plentiful. At one time

the Chimcera must

have been a less rare fish than it is now, for it has a Gaelic name, "Buachaille-an-Sgadain," the

Herring Herd or Herdsman. It was probably comparatively common in the

good old times, when even our more inland western lochs swarmed annually

with herring shoals, and so large was the capture, that the salt to cure

them, on which there was a considerable duty at the time, was frequently

retailed over a vessel's side at a shilling the lippy. The late Colonel

Maclean of Ardgour, who attained a great age, with intellect clear and

unimpaired, and who was most particular and exact in all his statistics,

has repeatedly assured us that, in his younger days, say a hundred years

ago, fifty

thousand pounds worth

of herring used to be captured annually in Lochiel alone. We don't

suppose that for many years past herring to the value of a tenth of that

sum have been caught in all the lochs between the Mull of Cantyre and

the Point of Ardnamurchan.

The reader probably knows what ringworm is—a

fungoid eruption on the skin, not uncommon in the spring and early

summer in children and young people of plethoric habits. There is a very

wide-spread belief over the West Highlands and in the Hebrides that

ringworm can be readily cured by rubbing it over and around once or

twice with a gold-ring—a woman's marriage ring, if it can be had, being

always preferred. In our younger days we recollect seeing the cure

applied on more than one occasion, whether with the desired result, or

ineffectually, we do not know—we probably little thought in those days

of kilts, cam-manachd, and

barley bannocks, of inquiring. For many years we had neither seen nor

heard anything either of the disease or of its popular cure, until, by

the merest accident, it came under our notice a few days ago. Riding

home one evening last week, we observed two little girls and a sturdy

long-legged haflin lad

sitting patiently in front of a cottage, the door of which was shut and

locked. The youngsters, rather better dressed than usual, had come from

a considerable distance, and we wondered what they could be doing there.

On mentioning the matter next day, we had the story in full as

follows:—The three were suffering from ringworm. The owner of the

cottage has a marriage ring of wonderful efficacy in curing this

epidermic distemper. They had come from one of the inland glens to be

operated upon, but the possessor of the ring was away in Glasgow, and

only returned home by steamer late that evening. When she did arrive,

the young people were duly manipulated and ring-rubbed

secundum artem; and

in four and twenty hours thereafter we were gravely assured they were

quite healed. Any gold ring is usually employed, but the particular ring

referred to in this case is much sought after on such occasions,

because, as our informant said, it is of "guinea gold," by which we

suppose very pure gold, with the least possible alloy, is meant; and

because it is the property of a widow who was married to one husband

more than fifty years. A belief in the virtue of gold rings in cures of

ringworm is, as we have said, very wide-spread and honestly held by

many. Whether, in common phrase, there is "anything in it," or the whole

affair is sheer nonsense, we shall not take it upon us to decide. We

merely submit a common and curious article of popular belief for the

consideration of our grave and learned dermatologists and the faculty at

large. One thing is certain,—the owner of the marvellous ring makes no

vulgar profit by her frequent use of it in such cases. She is in

comfortable circumstances, and the whole affair, as far as she is

concerned, is a mere labour of love.

Another popular cure, which for the first time came under

our notice recently, and which in many cases is really efficacious, as

we have heard averred by

those who have been benefited by its use, is the application of a

poultice of cold

tea leaves to

an inflamed or blood-shot eye. A handful of the leaves is taken from the

pot, and placed between two folds of thin cotton or muslin, and applied

to the eye at bed-time, kept in its place, of course, by a handkerchief

or other band tied round the head. In cases of weak or inflamed eyes

from any cause, this is reckoned, in this and the surrounding districts,

"the sovereignest thing on earth." And one can quite understand how tea

leaves, at once cooling and astringent, employed in this way, may

benefit a hot and inflamed eye. It is a simple application at all

events, and always at hand; and when more pretentious remedies are not

readily attainable, one would be unwisely prejudiced, if not actually

foolish, to suffer long without giving it a fair trial.

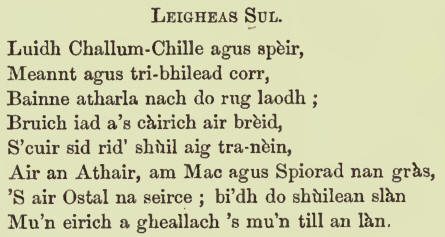

A less simple and less readily available cure for sore

eyes is the following in old Gaelic verse :—

In English, literally—

(Take of) St. Columba's wort and dandelion,

(Of) mint and a perfect plant of marsh trefoil,

(Take of) milk from the udder of a quey

(That is heavy with calf, but that has not actually calved),

Boil, and spread the mixture on a cloth;

Put it to your eyes at noon-tide,

In the name of Father, Son, and the Spirit of Grace,

And in the name of (John) the Apostle of Love, and your eyes shall be

well

Before the next rising of the moon, before the turning of next

flood-tide.

We were recently shown a great curiosity—a dirk sheath

said to be made of human skin. Its history, as related to us by the

owner, is as follows :—In the summer of 1746, about two months after

the battle of Culloden, a detachment of Saighdearan

Dearge, red

(coated) soldiers, or Government troops, was passing through Lochaber

and Appin on its way to Inveraray, the men amusing themselves, and

enlivening the tedium of the march, by burning and plundering as

they had opportunity. When passing through the Strath of Appin, a young woman

was observed in a field, busily engaged in the

evening milking her

cuw. A sergeant or corporal of the band leaped over the Avail into the

field, and

putting

his musket

to his shoulder, shot the cow dead

upon the spot; after which gallant

exploit he began

the most brutal ill-treatment

of the

woman. She, however, defended

herself with great

courage, and as

she retreated towards the

shore, she picked up a stone, which she

hurled at her persecutor with such good aim that it struck him full on

the forehead, stretching him for the moment senseless upon the grass.

She then fled towards a

boat that was afloat on the beach, and leaping in, rapidly rowed towards Eilean-bhaile-na-gobhar, an

island at a considerable distance from the mainland, where

she was safe

from further annoyance. The tradition is so minute and precise that the

heroine's name is given as Silas-Nic-Cholla, or

Julia MacColl; and our informant declared himself to be her

great-grandson. The sergeant, stunned and bleeding, was picked

up by his comrades, and carried to the place of halt for the night, near Tigh-an

Ribbi,

where, before

morning, he died of his wound. His

body was buried in the old churchyard of Airds, but was not

allowed to rest there. On the disappearance of the soldiers from the

district, the body was exhumed

by the people, and cast into the sea; not, however, before a brother

of Silas-Nic-Cholla flayed

the right arm from the shoulder to the elbow, and of the skin thus

flayed was made a dirk sheath, and this sheath we

saw and

handled with no little curiosity a week or two ago.

The sheath is of a dark brown colour, limp and soft, with no ornament

except a small virle of brass at the point, and a thin edging of the

same metal round the orifice, on which is inscribed the date "1747," and

the initials "D. M. C." There is no reason, we suppose, to doubt the

genuineness of the article, though we hardly expected to find human

skin—if it be human skin—of such thickness. It may, however, be partly

the result of the tanning process which it probably underwent, and of

time. In connection with this strange relic of a past age may be stated

the extraordinary fact—incredible, indeed, if it were not thoroughly

authenticated— that during the horrors of the French Revolution there

was a tannery of human skins for many months in operation at Mendon. The

raw material, so to speak, of this strange manufacture, was the skins of

the scores and hundreds that were daily guillotined. It is asserted that

"it made excellent wash-leather." Montgaillard, a prominent character of

the period, who had the curiosity to visit the works, and saw the

tanning process in full operation, makes the following curious

observation :—"The skin of the men was superior in toughness and quality

to shamoy; that of the women good for almost nothing, so soft in

texture, and easily torn, like rotten linen !" We have had some

rebellious revolutions, civil wars, and all the rest of it in Great

Britain and Ireland, with their attendant iniquities, bad enough in all

conscience, but the French may fairly boast of having beat us; a tannery

of human skins is a venture and enterprise that no one has been pushing

and patriotic enough yet to undertake amongst us, even when axe and

gallows wrought their hardest in days happily long since passed away. |