The

lily it if pure, and the lily it is fair.

And in her lovely bosom I'll place the lily there;

The daisy's for simplicity and unaffected air—

And a' to be a posie to my ain dear May.

"The hawthorn I will pu', wi' its locks o' siller grey,

Where, like an aged man, it stands at break o' day;

But the sonqster's nest within the bush I winna tak away—

And a' to be a posie to my ain dear May."

Mark that line in italics, and ponder its exquisite

tenderness. How it must have irradiated, like a sudden flood of sunshine

over a mountain landscape, the poet's heart as he penned it! Here you

have the germ of the doctrine afterwards more broadly taught by

Coleridge in the well-known lines of the Ancient

Mariner:—

"Farewell, farewell, but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding Guest,

He praycth well, who loveth well

Both man, and bird, and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things, both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all."'

We love The

Posie of

Burns for its own sake, but we love it all the more, perhaps, because

our attention was first directed to its sweet simplicity and tender

beauty by one of our earliest and kindest friends, himself a poet of no

mean order, the late Professor William Tennant, author of Anster

Fair, in

all its fantastical gaiety and homely mirth the most original poem,

perhaps, to be found in the literature of our country.

A gentleman who resides at present in Cheltenham, a cadet

of one of the oldest and most respectable families on the West Coast,

and himself the head of a house not unknown in Highland story, has been

so good as to send us a short Gaelic poem in manuscript, with a request

that we should give an English version of it. With this request we very

readily comply, such a task being to us a labour of love; the poem

itself, besides, being very beautiful, and the history of its

composition extremely interesting, as throwing some light on the manners

and customs of the olden times. The following prefatory note from the

MS. itself sufficiently explains the origin of this quaint and curious

Hebridean Epithalamium:—"It

was the custom in the West Highlands of Scotland in the olden time to

meet the bride coming forth from her chamber with her maidens on the

morning after her marriage, and to salute her with a poetical blessing

called Beannachadh

Baird. On

the occasion of the marriage of the Eev. Donald Macleod of Durinish, in

the Isle of Skye, this practice having then got very much into

desuetude, and none being found prepared to salute his bride

agreeably to it, lie himself came forward and received her with the

following beautiful address." "We present our readers with the original

lines verbatim

et literatim, precisely

as they stand in the MS., only omitting two lines that are partly

illegible from their falling into the sharp foldings of the sheet. The

sense and tenor of these lines, however, we have ventured to guess at

and to incorporate with our English version:—

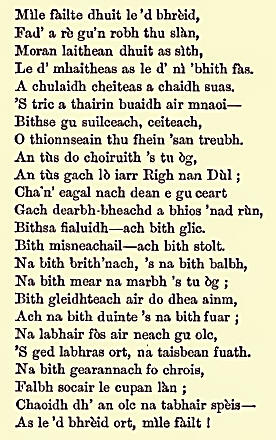

Beannachadh Baird

Whether with the sense of the above we have succeeded in

catching anything of its quaint beauty and tenderness in the following

lines, is for the reader to judge:—

A Baud's Blessing

Comely and kerchief'd, blooming,

fresh and fair,

All hail and welcome! joy and peace be thine;

Of happiness and health a bounteous share

Be shower'd upon thee from the hand divine.

"Wearing the matron's coif, thou seem'st to be

Even lovelier now than erst, when fancy-free,

Thou in thy beauty's strength did'st steal my heart from me.

Though young in years thou 'rt now a wedded wife;

O seek His guidance who can guide aright.

With aid from Him, the rugged path of life

May still be trod with pleasure and delight;

For He who made us bids us not forego

A single, sinless pleasure in this world of woe.

Be open-hearted, but be eident too,

Be strong anil full of courage, but be staid;

Aught like unseemly folly still eschew—

Be faultluss wife as thou wast faultless maid!

Guard against hasty speech and temper violent,

And knowing when to speak, know also to be silent.

Guard thy good name and mine from smallest stain;

In manner still be kindly, frank, and free;

If thou 'rt reviled, revile not thou again;

In hour of trial calm and patient be;

And when thy cup is full, walk humbly still,

A careless, proud, rash step the blissful cup may spill!

With this bard's blessing on thy wedded morn,

All at thy bridal chamber-door we greet thee;

May every joy of truth and goodness born

Through all thy life-long journey crowd to meet thee;

And may the God of Peace now richly shed

A blessing on thy kerchief-cinctured head!

The word breid in

the original, which we have rendered kerchief and coif,

was in the olden times the peculiar head-dress of married females, while

virgins wore their braided locks uncovered, a simple ribbon to bind the

hair, and occasionally a sprig of heather or modest flower by way of

ornament, being the only head-dress that could with propriety be worn by

a maiden in the good old anti-chignon days of our grandmothers. The

Highland maiden's narrow ribbon for binding the hair was in the south of

Scotland called a snood, probably

from the old English snod—"neat,

handsome"—a word still in use in the English border counties. In the

south, even more pointedly than in the north, the emblematical character

of the maiden ribbon or snood was recognised. It was only when a maiden

became an honest, lawful wife that the coif—also called curch and toy—could

be worn with propriety. If a damsel was so unfortunate as to lose

pretentions to the name of maiden, without acquiring a right to that of

matron, she was neither permitted to wear that emblem of virgin purity,

the snood, nor advanced to the graver dignity of the coif or curch. In

old Scottish songs there occur many sly allusions to such misfortunes,

as in the original words of the popular tune of "Ovver the muir amang

the heather"—

"Down amang the broom, the broom,

Down among the broom, my dearie,

The lassie lost her silken snood,

That gart her greet till she was wearie."

And in a verse of a curious old ballad that we took down

some years ago from the recitation of a grey-headed Paisley weaver—

"And did ye say ye lo'ed me weel?

Then, kind sir, ye maun marrie me;

For that I maunna wear my snood

Aft brings the saut tear to my ee."

The reverend author of the above lines was probably born

about the year 1700, or perhaps ten or twenty years earlier, for we find

that he died a man well advanced in years in 1760. In the Scots

Magazine of

that year there is the following notice of Mr Macleod's death :— "Jan.

12th.—At

Durinish, in the Isle of Skye, the Rev. Donald Macleod, minister of that

parish, a gentleman, says our correspondent, who adorned his profession,

not so much by a literary merit, of which he possessed a considerable

share, as by a consistent practice of the most useful and excellent

virtues. To do good was the ruling passion of his heart; in composing

differences, in diffusing the spirit of peace and friendship, in

relieving the distressed, in promoting the happiness of the widow and

orphan, his zeal was almost unexampled, his activity unmeasured, his

success remarkable. It is almost unnecessary to add that he lived with a

most amiable character, and died universally regretted."

A somewhat curious circumstance is the following :—One of

the Rev. Mr. Macleod's daughters was married to Macleod of Berneray, she

being that gentleman's third wife.

Berneray was at the date of this third marriage seventy-five years of

age, notwithstanding which he became by this lady the father of nine

children. He

lived a hale and hearty old man till he was upwards of ninety. He was

reckoned in his day a splendid specimen of the stalwart, sterling,

straight-forward, and chivalrous Highland gentleman, "all of the olden

time."