|

BY this time the

improvements had been, or were said to be, completed at Aline, and

thither did I betake myself alone, R. M. having gone over to the

mainland for some shooting.

Before entering upon life

in the Lews, it would be as well perhaps to take the opportunity of

saying something about the events that had taken place in that country a

few years previously to our location there, and which were at that time

sowing a seed that was hereafter to bring forth much fruit. I. do not

want to enter into a history of the Lews—how the Fife lairds took

possession of and held it—how they gave place to the M‘Kenzies. Suffice

it to say that some six or seven years before our arrival, the present

owner, Sir James, then Mr. Matheson, bought it of Mrs. Stuart M‘Kenzie,

of Seaforth ; and a very fortunate purchase for the said country it was,

for he. had just returned from China with his pockets full of gold, and,

not knowing well what to do with it, lavished it broadcast on his

newly-acquired property. The potato crop failed, and the famine took

place two or three years after he came in. The new proprietor had the

means of keeping his people alive, and right magnificently did he do his

work. Though he may eventually have got back some part of the large sums

he had advanced for food, in labour on his numerous buildings and

improvements throughout the country, yet—honour to whom honour is due!

—but for Matheson, the Lewisians would have starved (there was no

poor-law then), and deservedly should he have his niche among the

benefactors of mankind. Besides this, he made roads where none were

before, and opened the country. By great outlays he established regular

steam navigation between Lewis and the mainland, thereby, alas ! making

its existence known—which then it was not—to an inquisitive public. By

putting on two steamers of his own, he made a trade, which, when given

up by himself, Glasgow was willing to take up. He built a very good slip

for the building and repairing of vessels. He built a good, commodious

castle, and kept constantly at work a large body of the Stornowegians in

the various works and improvements about it.

He introduced gas; and,

though last, not least, a good system of agriculture; he set up a good

model farm himself, and did what neither here nor hereafter will he ever

be forgiven for—he drained and converted into good land the best snipe

ground in the country—viz., that round Stornoway. Well and worthily,

then, has he merited the baronetcy the Government gave him, the very

year, I think, we reached the Lews. But yet, with all these claims to

respect, the proprietor lacked one quality. Having passed the chief part

of his life in the East as a diligent and successful man of business, he

was ignorant of everything connected with sport; he held sportsmen in no

very high estimation, considering them as eminently selfish. He fell

into the very common error of thinking that, because they were well

acquainted with their own subjects, they must consequently be profoundly

ignorant of all others. In fine, he kept a bountiful good mansion at a

bountiful good rate, was as hospitable as a Highlander, and, when

kindness was wanted, as openhanded as he was kind-hearted.

I arrived, as I stated,

at Aline by myself, and came in for a very cheery, exciting scene —by

way, I presume, of welcome. There had been a long-vexed question pending

between Lews and Harris—the decision of the boundaries. It was now

drawing to its close. The Dean of Faculty (afterwards Lord Colonsay) and

several of the Scotch lawyers concerned in this suit—pending since the

Deluge—had gone round to Loch Raisort to mark the ground, accompanied by

the pointers-out of both boundaries from the respective countries, and

by my friend, Captain Burnaby, and his sappers, the Chamberlain, and a

host of people.

A steamer had also been

sent up to accommodate many of the party, and the said vessel was well

laden with good viands and liquors for their creature comforts. And

pleasant indeed were those Scotch lawyers—when were they otherwise than

capital company? Lord Colonsay to great legal knowledge added the

deepest insight into the good qualities of a, deerhound of any man I

ever met; and from him I got a cross of his famous dog that was the

model for the hound that lies at Sir Walter Scott’s feet in the Memorial

in Edinburgh. I was younger then by many years, and had an Irish story

or two for them that tickled their fancies, and a pleasant night we

passed. There were pipers, of course; and how they danced, despite all

the anathemas of the Free Kirk!

Each party danced his

best for the honour of his country and of the boundary he had pointed

out and sworn to, and which, I do verily believe, would have been given

in favour of Harris but for too much proving. An old patriarch swore to

some cinders placed years ago by his ancestors as a landmark, but which

turned out to be the remains of a fire lighted there by the sappers some

four months back. This was, as you can conceive, damaging.

Next day I sent such of

the lawyers as could fish to do so whenever they liked, and Burnaby and

I went to Loch Larcastal, a loch in the Park, to get at which we had to

row across Loch Seaforth, and then walk about seven miles, a stiff pull

over the shoulder of Ben-more ; but the loch is a good one, and the

sea-trout run large. It was a good hard day’s work.

Next day Burnaby went. I

was left alone in my glory, and, like Robinson Crusoe, had time, to look

over our possession and consider its real capabilities. Our sport

consisted of deer-stalking, sea-trout fishing—for there were but few

salmon—and grouse shooting. Our ground was not forest, though the Park

(part of our ground) would, if the sheep were taken off, make a very

beautiful, forest. It is a large tract of country—almost an island; for

Loch Seaforth on one side, and Loch Erisort on the other, run very close

to one another at high water. It contains over 75,000 acres—some very

fine hills for deer, with excellent feeding-ground, and its venison is

the best in the Lews.

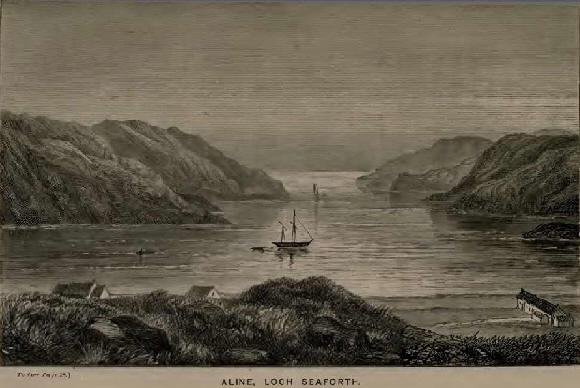

In former times, in the

time of the M‘Kenzies, the late Lord Seaforth tried to make a forest of

the Park by building a wall across from Loch Seaforth to Loch Erisort,

to keep the deer in; but this had long ceased to exist. But the great

drawback to the Park then was, when it was part of the Aline shooting,

that between the house of Aline and it lay Loch Seaforth—a beautiful,

picturesque object in fine weather, but in bad—which it sometimes can be

in those latitudes—not the pleasantest place in the world to cross,

except in a very good sea-boat, manned by four good oars and a good

coxswain. There were days in which it was no pleasant work getting there

or back, and this passage was a great damper of sport. Moreover, there

was in the whole of this Park but one small bothy, in which the

sportsmen, gillies, and stalkers could put up— and what a den it was! I

never shall forget the first day we got there—wet, of course. I had

sliot over, E. M. had stalked. The roof let in the rain, the floor was

earth; more smoke came into the room than went up the chimney. But we

were tired and hungry, and turned soon into those holes in the wall

called, Scottice, bed-places. In the morning—it had rained all night—the

floor was an epitome of the Lews— land dotted with lakes ; and, I

remember well, we had to get turf creels or bits of old planks to lay

down like hearthrugs by our beds, to step on as we rose. But what will

not deerstalkers go through ? Then, too, we had the best and gamest

stalker I ever knew, and the most honest and plucky of men. Long may you

live, Murdoch McAulay, and may I be spared, as they say north, to kill

another stag with you, and that this year!

I must stop here a moment

to mention an instance of McAulay’s pluck. An individual with whom he

was stalking knocked a stag over, and McAulay went on to cut his throat

or bleed him. The animal, to all appearance dead, jumped up and pinned

him against a bank by a burnside. He had just time to seize the animal

with both hands by his horns, and being very strong in the arm, and with

his back to the bank, held it at bay. He called out to the slayer of the

deer to come on and stick the animal with his knife, that had fallen in

the struggle; but the cautious gentleman—shall I call him such ?—had no

intention of so doing, but kept tickling and infuriating the already

sufficiently-enraged beast by sundry pokes and prods behind. M‘Aulay,

seeing this, interfered—“If you can’t do better than that, stop, or I

shall be killed; for I can’t hold out much longer! Put my knife on the

bank close by me, with the haft towards my hand, and get out of the

way!” With great difficulty the hero was induced to approach near enough

to do as he was told. McAulay then, watching his opportunity, let go one

hand, seized his knife, and buried it in the stag’s heart. I never asked

him whether he ever stalked again with his gallant comrade.

Murdoch is a first-rate

boatman—cool, and knowing his work well. Look at him running down steep

crags after a wounded stag, and you will almost shudder for his neck;

and if you are in for a scrimmage out of which you cannot get, look over

your right shoulder, and be sure you will find McAulay close up.

Lewid and Carneval, the

hills just above Aline, were good hills for deer, but they also were

under sheep, and of course liable to constant disturbance from the

shepherds, who are always doing something with those pests of all

sport—Highland or Lowland—gathering or driving them for some purpose or

other. You are also very much dependent for your sport on these two

hills upon the terms on which you are with the tenant of the Harris

shootings. The boundary line between Harris and Lewis running just

across Lewid, you cannot, in certain winds, stalk it without the

permission of Harris to go into their ground to get at it. Fortunately,

we were ever on the best of terms with Harris and its shooting tenants,

and received from them every permission that could assist us in our

sport in any way. We had their permission to fish their lochs—the best I

ever came across—and shoot their woodcocks in their fine glens. Many and

many pleasant days have I had with those “ forays into Harris,35 as we

used to call them.

With this permission, we

found Lewid and Carneval very useful stalking hills—close at hand, and,

therefore, very convenient; commanding fine views of Loch Langavat and

Glen Langan, and looking across to the proprietor’s forest of Kenrisort,

into which we anxiously peered. Woe betide the good stag that came out

to see the world on our side!

There is one great

drawback to the stalking of the Lews. The stag's are not fit to shoot—

at least as far as heads are concerned—till at least a month after the

mainland. The velvet, as a rule, is never off the horn till the very end

of August, and rarely completely till the middle of September—at least,

that is my experience ; and though you may shoot stags till the middle

or 19th of October (though their necks swell long before that), yet,

taking the lateness of the season and the climate into consideration,

the stalking season is both late and short. Of course there are the

hinds, and, as far as skill goes, every one knows how much more

difficult those fit to kill are to stalk than stags; yet few, I should

think, would care much for stalking, if there were nothing but hinds to

shoot.

Our fishing was almost

entirely loch-fishing; for though there were short streams running from

Loch Georgium and Loch. Stroundavat to Loch Seaforth, we scarcely ever

got fish in them. Sea-trout were caught, and good ones, in these two

lochs, but seldom salmon —why or wherefore I never could make out, for

there were fish. There were also in the Park the Skipnaclet Lochs, the

Eischkin Lochs, and Loch Larcastal—to my mind, the best loch in the Lews

for large sea-trout. All three, however, were difficult of access from

Aline, and it was an expedition to reach them; but still I managed to

get sport in them. Now, however, that the Park shooting is taken away

from Aline and made into one shooting, and a good lodge built in it, all

this fishing is more accessible.

The grouse shooting we

expected not to be very first rate, as the grouse disease was in the

island. But I did not expect, nor do I ever remember seeing, so large a

space of ground so utterly denuded of game. Grouse, as every one knows,

are later the farther north you go. I had shot in Ross-shire before, and

the birds are at least a fortnight later there than in the more southern

counties. In the Lews, as a rule, I do not hesitate to say that, though

you may shoot grouse at the beginning of September, they are a month

later than the mainland birds, and should not be shot before the middle

of September.

I never, probably, shall

forget my essay at grouse shooting in the Lews. I shot from Aline to

Balallan Bridge (seven miles) with' good dogs, and during my progress

killed three birds (all I saw), and those three scarce fit to pick up.

E. M. and I shot another day together, walking miles, and only finding

six birds, which we killed for the sake of the dogs. Poor things ! they

fairly gave up the ghost, and demurred to hunting.

Never in my life before

or since do I remember such a shooting season. There was actually

nothing to shoot over the whole of our ground, containing about 130,000

acres. We killed this year—two guns, R. M. and myself— seventy-six brace

of grouse. Moreover, I shot over the whole of the adjoining Soval

shooting, containing some 75,000 acres, and killed on it about

thirty-five brace more. Had I not seen it, I would not have believed

that disease could have created such havoc, and we began to despair of

grouse shooting, at least for the seven years’ lease we had just taken.

It is also fair to state

there was another reason to account for the small amount of grouse to be

found at that time in any part of the island of the Lews I then shot

over. As I mentioned before, the survey of the Lews was then going on,

and parties of Burnaby’s sappers were stationed all over the country, in

either tents or huts. Pew of these quarters were without one gun, one

fishing-rod, and one good terrier, at least. Of course they made good

use of their leisure hours, and, though their commander looked after

them to the best of his power, they poached like fury—at least, they

were great fools if they did not. What, then, with the disease and the

survey, which went on till 1853, the shooting tenants had not a blooming

time of it; and we often thought and talked about the hardship of

putting the country to great expense in surveying such a place 'as the

Lews. I believe that afterwards the land survey was of service to the

Admiralty survey of the sea-coast, which was indeed a blessing to those

navigating these seas. Be this, however, as it may, never anywhere that

I have shot did I see so little to be got as at Aline. I spent the whole

winter there, and my diary records the most minute entries. The weather

was atrocious, such as one must have inhabited those latitudes to

comprehend. There were very few snipes or woodcocks, and the only sport

I got during the year was when I went down to Stornoway to stay with

Burnaby, and shot with him. The best snipe shooting in the island was

about Stornoway, very often near the town, and within five to nine

miles’ distance round. Grouse, too, did not seem to have suffered so

much in those regions as about us. Altogether, as far as sport was

concerned, my first season in the Lews was not cheering. |