|

WITH the tragic and

untimely death of Alexander III. Scotland was to enter upon a long, cruel,

and desolating war to maintain her independence against the aggressive

policy of Edward I. During this troubled period the prosperity which

Alexander III. and his immediate predecessors, the "Kings of

Peace," had done so much to build up by their wise and friendly

policy towards England was completely destroyed. Alexander’s little

granddaughter, the Maid of Norway, was the nearest heir to the throne. The

Scots agreed with her grand-uncle, Edward I., that she should become the

bride of his son, Edward, Prince of Wales, and in this way bring about the

union of England and Scotland under one sovereign. But this child of many

hopes, the little Maid, died on the voyage from Norway, leaving to

Scotland a disputed succession which gave an opening for the mischievous

interference of Edward I. The

English king’s attempt to make Scotland a province of England changed

the two otherwise friendly countries into bitter foes. The three centuries

of devastating wars that followed made Scotland very unlike the happy and

prosperous country she was in the days of Alexander III.

In 1296 Edward captured Berwick, and, by a savage

massacre of its inhabitants, reduced that city of merchant princes to

the market town it has ever since remained. Mounted on his great war

horse Bayard, Edward led his army northwards and took up his quarters at

Holyrood, while his fleet, laden with supplies for his troops, anchored

off Leith.

During his progress through

Scotland the landowners of the country great and small, churchmen, nobles,

and the chief burgesses, were summoned to do homage and swear fealty to

the conqueror. The names of all who performed these acts of homage have

been carefully preserved on four rolls of parchment known as the Ragman

Roll. These rolls form a valuable record of the lands, though not always

of their owners, in our own immediate district at this date, and to them

we are indebted for any little light that gives us a peep at the condition

of things in and around Leith during those dark and troubled days. It is

there that we find for the first time the name of an Edinburgh magistrate,

namely, William de Dederyk, Alderman, as the provost was called in those

early days.

There, too, we find the

name of Adam, parson of Restalrig, the parish church of Leith at this

time. King Edward had seized the lands of Holyrood, so that the greater

half of Leith passed into the hands of the English; but Abbot Adam and all

the canons swore a solemn oath of fealty to the English king in the Abbey

chapter-house, a few remains of whose foundations may still be seen on the

lawn at Holyrood. In those days men did not observe very faithfully feudal

pledges not over willingly given, so, to add to the solemnity of their

oath, the abbot and canons were compelled to swear over the sacrament

bread—the Corpus Christi or body of Christ—brought

from the high altar dedicated to the Holy Rood.

In this way was the convent

again put in possession of its lands, no doubt to the joy of its sorely

troubled vassals in Leith, who rejoiced to have the good abbot and canons

come among them, as they were wont to do. Thus did the policy of Abbot

Adam of swearing fealty to Edward I. secure the safety of his monastery

and the fortunes of his part of Leith during his remaining years. But they

were difficult and dangerous times, and it was no easy matter knowing what

course to steer. The Abbey with its adjacent possessions was doomed to

suffer grievously at the hands of the English before they would yield to

acknowledge Scotland’s independence.

The lands of Holyrood were

not the only parts of Leith to come under King Edward’s peace at this

time. Farther down the roll we find the name of John de Lestalric and that

of his near neighbour, and no doubt good friend, Geoffrey de Fressinglye,

Lord of Puddingston. A few years later, however, De Lestalric and his

companion-in-arms, De Fressinglye, were to forfeit their lands of

Restalrig and Duddingston for being among the first to enlist under the

banner of Robert the Bruce and doing their "bit" in the long and

strenuous fight for Scotland’s independence. In this struggle they were

either killed or worn out with hardships and toil, for, like Randolph and

the Good Lord James, they both died comparatively early in life.

The early struggle against

England is rather an obscure period of Scotland’s history, and but for

the immediate neighbourhood of the mighty fortress of Edinburgh Castle,

which was strongly held for England until the year of Bannockburn, and

which dominated and held in subjection the whole neighbourhood, Leith

might have dropped out of the history of this time altogether; but, as it

is, it bulks more largely, if less romantically, than Edinburgh itself in

the story of those stirring and chivalrous days.

No sooner did the English

garrison take up its quarters in Edinburgh Castle than English ships began

to arrive in Leith harbour with large supplies of all kinds, the various

items of which show us that grains and wines were then, as with us to-day,

among the chief imports. These stores, many of which came from Berwick

under the protection of the traitor Earl of Dunbar, who was ever on the

side of England, included wheat, barley, malt, meal and wines, munitions

of war, and "Eastland boards" for the manufacture of Edward I’s

great war machines.

Many of these stores were

reshipped in smaller craft for the English garrisons at Stirling,

Clackmannan, and other places of strength farther up the Forth. In 1303,

for example, an engine capable of throwing missiles weighing one

hundredweight was sent with munitions from Edinburgh Castle to Edward I.,

who had been for three months baffled in the capture of Stirling Castle by

the vigilance and skill of that gallant knight and near neighbour to the

Leith folks of those days, Sir William Oliphant of Muirhouse, just beyond

Pilton.

For the protection of these stores a detachment from

the Castle garrison was posted in Leith, no doubt in some fort on the

Shore near the Broad Wynd, the seaward limit of the town in those days.

There were no great docks in Leith at this time, with their miles of stone

quays. The Shore, which extended as far as the present Broad Wynd, was

then the only quay for the loading and discharging of vessels. How

picturesque must have been the scene, with the green and wooded banks of

the winding river, and the old-world ships with their great high sterns,

from which their captains could overlook and direct all that was being

done! How great also the noise and bustle among the English soldiers as

they loaded their lumbering and creaking wagons with their share of stores

for Edinburgh Castle!

There was no Leith Walk

then, nor for many centuries after, and we must put from our minds all our

notions of roads derived from the fine highways of our own day. The Easter

Road, Bonnington Road, and the Restalrig Road were then mere tracks across

the heathery waste that, but for the cornfields adjacent to the two towns,

filled all the area between the port and the city, if we may so dignify

the four hundred or more thatched dwellings that made up the Edinburgh of

the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. The most direct road, and,

no doubt, the one most used by the English soldiery, was the Bonnington

Road, which led cityward by way of Broughton. It was at this early date,

one may be sure, the most frequented and the best of the three tracks, for

the monks of Holyrood to whom it belonged were great roadmakers.

In the spring of 1314 many of those same English

soldiers who had been accustomed to drive so merrily with munitions and

stores between the Castle and the Shore fell under the swords of Randolph

and his companions when they captured Edinburgh Castle by climbing the

Castle rock overlooking Princes Street—the most brilliant feat of arms

of that heroic age. Immediately afterwards the English garrison posted in

Leith burnt all their shipping and stores and sailed away southwards to

Berwick, then a great English naval and military base for supplying and

fitting out expeditions against Scotland.

A few months later, on a

bright day towards the end of June, the great army of Edward II., on its

way to Bannockburn, and anticipating an easy and triumphant victory,

encamped between Edinburgh and Leith to receive supplies from the fleet

which lay off the harbour. This great English host, though perhaps only a

fourth as large as the chroniclers would have us believe, was yet imposing

enough to dismay the Scots leaders as they saw it approaching them at

Bannockburn.

The womenfolk of Leith from some safe retreat watched

the mighty host march away westwards, and trembled at the sight when they

thought of their sons and husbands who had followed the banner of their

gallant leader, Sir John de Lestalric, to join the king at Stirling; for

Leithers in the old days, as in these, were loyally patriotic, and ever

among the foremost to rally to their country’s need. There was one

Leither, however, a sailor, whose name, preserved for us in a pay sheet of

this time, shows him to have been in the service of the English. This is

not surprising, considering that they had held Leith as one of their chief

bases of supplies for nearly twenty years. Nicholas of Leith, mariner, was

with the English ships at Berwick, and may at this very time have come

with the fleet to Leith Roads.

How unexpected must have been the sight, and how wild

their joy, when these same Leith womenfolk saw some five hundred fugitive

horsemen, all that was left of the flower of England’s chivalry that had

ridden past Leith with so brave a show some three days before, pass in

headlong flight on their way towards England. They were led by a traitor

Scot, and followed close at heel by the Good Lord James with some sixty

men, too few to attack, but not too few to cut off stragglers and keep the

main body on the move.

In spite of his crushing defeat at Bannockburn, Edward

II. obstinately refused to acknowledge Scotland as a free and independent

country and Bruce as its king. The war was, therefore, resolutely carried

on, mostly by invasions of England on the part of the Scots, under the

gallant and skilful leadership of Douglas and Randolph. Provoked by these

numerous and destructive raids, Edward determined, in 1322, on another

attempt to crush Scotland. This invasion brings Leith once more into

notice, for here Edward encamped for three days to await the arrival of

his fleet with supplies. Bruce followed the tactics Wallace employed

against Edward I. before the Battle of Falkirk. All cattle, corn, and food

of every kind were secreted far from the English line of march. All

merchandise was, no doubt, stored within the Castle. Edward found no

cattle in Lothians save one cow too lame to be driven away like the

others.

But where did the people of Edinburgh and Leith betake

themselves? During an English invasion some sixty years later it is

recorded that they transported themselves and their goods across the

Forth, previously carrying off the straw roofs of their dwellings, so that

when the English entered they found only roofless and empty houses. But

the Leithers did not always betake themselves so far in times of invasion,

for there were many safe retreats among the woods, marshes, and lakes by

which the Leith and Edinburgh of those early centuries were surrounded,

and to which Edinburgh may have owed its name of Lislebourg, so

persistently used by Queen Mary, Mary of Guise, and the French of the

sixteenth century.

Starvation compelled the English to retreat; but before

doing so, to the horror of the whole neighbourhood and the grief of the

people of North Leith, the English, as Fordoun, the father of Scottish

history and the greatest of our old-time Scots chroniclers, tells us,

"sacked and plundered the monastery of Holyrood, and brought it

to great desolation," for Edward II. lacked

not only the wisdom but also the piety of his father, Longshanks, who was

ever a devoted worshipper of the saints and a lover of monasteries. Then

the Leithers returned, and quickly and easily rethatched their dwellings,

and settled down to the old way of life, to work with redoubled energy to

repair their losses; for in those days, as, indeed, all through their

history, Leithers had to, and did, live up to their town motto of ‘‘Persevere."

Standing as it did in close

proximity to Edinburgh, the goal of most invading English armies, and

never possessing, except for a very short period, any protecting walls,

Leith suffered even more than Edinburgh at the hands of the "auld

enemy." Her houses, largely composed of timber or rude stonework and

thatch, were easily and speedily restored. They had certainly no

architectural beauty. The ordinary houses of those days were little better

than huts, with little furniture and less comfort; but

as Leithers had never known anything better, these troubles distressed

them little. Such frequent dislocation of their trade and commerce,

however, must have greatly retarded the progress of their town. At last

the English recognized that their only wise course was to acknowledge

Scotland’s independence, which they did by the Treaty of Northampton in

1328, when Scotland gained all she had striven for, and Bruce just saw the

accomplishment of his great life work, for he died the following year.

And then it seemed as if

all King Robert’s great work was about to be undone, for the peace

concluded at Northampton lasted only two years. Edward III. now repudiated

what the English called the "shameful treaty "

of Northampton. Edward Baliol claimed the throne, and Edward III.,

hoping, like his grandfather, to become Scotland’s overlord, aided him,

and once more the land was cruelly devastated by English invasion. In 1335

Edward III. ordered Edinburgh Castle to be rebuilt and fortified, and for

this purpose much Eastland timber was brought into Leith and then

transported to Edinburgh. The work was carried out under Sir John de

Stirling, an exceedingly able and active officer, who, on taking over his

command, reported that there was no dwelling in the said Castle save a

little chapel (St. Margaret’s), partly unroofed, showing with what

reverence Randolph had preserved it, and how completely he had destroyed

the Castle as a fortress. Stirling’s accounts, still preserved, form a

valuable record of the condition of things in our neighbourhood under

English rule.

Sir John de Lestalric and

his companion-in-arms, Geoffrey of Duddingston, were now dead, whether

slain in battle against the English or not we have now no means of

knowing. Each had been succeeded by his son—true "chips of the old

blocks," for both were forfeited for loyally and nobly supporting the

cause of Scotland and freedom against Edward III., while many renegade

Scots saved their estates by taking the English side. With the English

garrison in Edinburgh Castle were some twenty Scotsmen, of whom not one

belonged to either Leith or Restalrig, showing that the hearts of his

vassals were with their forfeited lord.

Leith now once again became

the chief port on the east coast for English supplies, and here the

English occupied De Lestalric’s house, but whether as a place of

residence for their garrison or as a storehouse for supplies—more

probably the latter—we are not told. The names of many of the ships

bringing supplies from the south to Leith are recorded—such as the Mariola,

St. Nicholas, and the Goddys Grace—their saintly names in no

way deterring their captains and crews from indulging in a little piracy

when occasion offered.

Sir John de Stirling commandeered a fleet of eighteen

boats from Cramond, Musselburgh, and other places, to be moored at Leith

for the use of his garrison, and now and again the governor’s account

books give us a peep at the rather exciting incidents Leith sometimes

experienced during the English occupation. Sir Andrew Murray of Bothwell,

the courageous son of the heroic companion of Wallace, was besieging Cupar

Castle in Fife, skilfully defended for the English by William Bulloch, a

clergyman of great military talent who had mistaken his calling. Sir John

de Stirling determined to cross the Scots Water—that is, the Firth of

Forth— and relieve it. For this purpose he had gathered together at

Leith a fleet of thirty-two vessels and two hundred and twenty-four

mariners. Suddenly crossing the Forth with the whole of the Edinburgh

garrison, he successfully accomplished the relief of Bulloch, and returned

to Leith within the marvellously short space of four days. But then Edward

III., unlike his grandfather, knew how to choose his officers.

Sir John de Stirling, however, skilful commander as he

was, had still more skilful opponents, for at this time Sir Alexander

Ramsay of Dalhousie, whose ruined castle still stands above the waters of

the South Esk at Cockpen, had gathered together a band of homeless

patriots, among whom, perhaps, were the young De Lestalric, and the lords

of Duddingston, Craigmillar, Liberton, Braid, Dean, Inverleith, and Pilton—all

forfeited and outlawed at this time for their resistance to English

aggression. They had their fastness within the ancient caves among the

cliffs at Hawthornden, near Roslin. From these, at unexpected times, they

would pounce down upon the soldiers of Sir John Stirling as they convoyed

supplies between Leith and Edinburgh for the Castle garrison. Sir

Alexander Ramsay was one of the most distinguished warriors of that time,

and he and his outlawed troop were worthy successors of those who had won

Bannockburn. They were the heroes of many daring deeds. With such men as

these on the patriotic side, and such women as "Black Agnes" to

inspire them with courage, the English and Baliol soon lost their hold in

Scotland when their garrisons were driven out of Edinburgh and Leith.

In April 1341 Edinburgh Castle was captured by a clever

stratagem planned by Bulloch (who had been won over to the Scots side),

Sir William Douglas the Black Knight of Liddesdale, and other heroes,

aided by three Edinburgh merchant burgesses, William Fairley, Walter

Curry, and William Bartholomew. A merchant ship belonging to Walter Curry

was freighted from Dundee with a cargo of provisions for Leith. At Dundee

they privately received aboard their ship Douglas, Bulloch, and some two

hundred other bold and daring spirits, and, under pretence of being

English merchantmen—they had shaved their beards in the Anglo-Norman

manner—anchored off Leith. They then offered for sale to the English

commander of Edinburgh Castle their cargo of "biscuit, wine, and

strong beer all excellently spiced," and were told to bring it to the

Castle at an early hour in the morning, "lest they should be

intercepted by Dalhousie and other Scottish knaves."

Early next morning the laden wagons set out from the

Shore under the care of armed men disguised as sailors, and eventually

reached the Castle. The gates were at once opened, and at the entrance the

wagons were so halted that it was impossible either to close them or to

let down the portcullis.

A shrill blast from a bugle-horn brought Douglas and

his friends, who were lurking in the neighbourhood. After a desperate

conflict the garrison was overpowered. In this way Leith and Edinburgh

were freed from English rule until the days of Cromwell. The descendants

of William Fairley long held the estates of Braid and Bruntsfield, but now

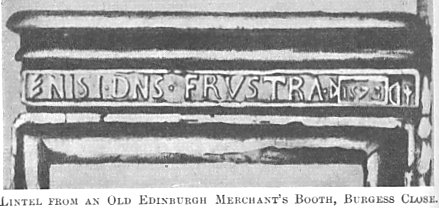

live in Ayrshire. The merchant booths of Fairley, Curry, and William

Bartholomew were the last three on the south side of the High Street, just

before coming to St. Giles’ Church. Walter Curry’s, the last of the

three, stood exactly where the City Cross stands now. How many Leith and

Edinburgh people who pass this spot to-day know aught of these three

merchants who had their booths here, and who on that early morning some

six hundred years ago played so heroic a part in their country’s story?

|