|

THE ‘Forty-five proved to

be the end of civil strife in our country, for, whatever wars Britain

might wage abroad, the people were determined to have settled and ordered

government at home. In no other way could trade flourish and progress be

made. From the period of the ‘Forty-five, then, a wonderful change came

over Scotland. Instead of nursing her wrongs as she had hitherto done, she

now began to realize, and to take advantage of, the many benefits and

opportunities the Union had really put in her way. The two peoples did not

love each other any the more. The notorious John Wilkes, a few years after

this time, stirred up in the hearts of Londoners strong feelings of hatred

and contempt against all Scotsmen for the share the Marquis of Bute had in

the unpopular Treaty of Paris which closed the Seven Years’ War. Every

year as the king or queen’s birthday came round, almost right down to

the close of Queen Victoria’s reign, the Leithers, at first from revenge

and later from custom, would burn John Wilkes in effigy under the name of Wully

Wulks, because they had really forgotten who he was.

Up to this time Leith had

practically not grown beyond her mediaeval bounds. Farming was still an important

occupation of its inhabitants. Fields of pease, oats, and barley occupied

all the land between St. Anthony’s Port and the Netherbow. In Easter

Road still stand the farm-house and steading of Lower Quarry Holes, whose

tenant, Robert Douglas of Coatfield, in 1730, like so many indwellers of

Leith, under the name of maltman combined the vocations of farming and

brewing, and was a member of the Burlaw Court, which met in the Doocot

Park beside the Links. But just after the period of the ‘Forty-five a

change began to show itself in the landscape viewed from Leith. Turnips,

soon to be followed by potatoes, now became a field crop. To protect these

crops from the wandering cattle the fields had to be enclosed by dikes and

hedgerows.

Farmers had no longer to

slaughter their cattle for lack of winter food for them after the stubble

fields had been eaten bare. They could now be fed on turnips. Salt meat,

varied with pigeon pie, then ceased to be the winter fare of the people of

Leith, as it had been for centuries; and the dovecots in the gables of the

houses, around which pigeons were ever cooing and fluttering, now became

silent and untenanted, and were put to other uses. A few of these old

dovecot gables, with their alighting ledges and entrance holes for the

birds yet survive in Leith, as at 32 Shore, and remind us of the days when

food was less plentiful than with us now, and pigeons had to be kept to

eke out, and to add variety to, the winter supply.

Leith now began to advance

with steady progress and has continued to do so down to the present time;

for although Britain was almost constantly engaged in wars on the

Continent during the second half of the eighteenth century, these did not

injure Leith’s trade to anything like the extent that England’s wars

with France and Holland had done during the century before. Then Leith’s

overseas commerce was almost her only trade, but now, in the latter half

of the eighteenth century, she had many home industries as well as foreign

trade. The raw material for her manufactures she imported mostly from the

Baltic—a trade route on which Leith vessels were not likely to encounter

so many of the enemy’s warships and privateers as in the days when her

commerce was chiefly with the Netherlands. Furthermore, throughout the

long French war the Government, at the suggestion of the Leith and

Edinburgh merchants, among whom Mr. Gladstone’s grandfather took the

lead, encouraged neutral vessels to bring in cargoes of raw material

necessary for our home industries even from enemy countries, a policy by

which the linen factories of Edinburgh and the Leith sail-cloth works and

rope-walks were enabled to carry on all through the war.

During the first

twenty-five years after the ‘Forty-five Leith’s shipping trade

increased sevenfold. That was due to several causes, one of which was that

new industries, like the oil-works of Messrs. P. and C. Wood and the new

sugar-house in Water Street, were constantly being founded, and old ones,

like the glass-works and the shipbuilding yards, being further extended

and developed. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the glass-works

had increased from two to seven.

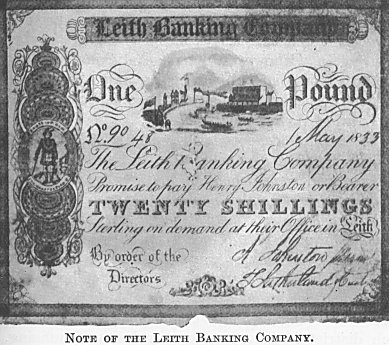

This

noteworthy industrial and commercial expansion was due mostly to two

factors, without whose aid it could not have taken place; the one was the

rise and development of banks, and the other was the Turnpike Road Act of

1751. The first of the great banking companies to open a branch in Leith

was the British Linen company, which, as its name indicates and as its

more recent note issues show, was first founded as a linen company, and

then forsook trading in linen to take up banking; but the Leith Banking

Company had already built and established itself in the neat little domed

building in Bernard Street, now occupied by the National Bank. It failed

in 1842, and had to close its doors. It was followed by the Edinburgh and

Leith Banking Company, a very wealthy corporation, now merged in the

Clydesdale Bank. Money was very scarce in Edinburgh and Leith in the

eighteenth century. To the credit system of these banks, by which Leith

merchants were able to finance their transactions, is largely due the

Position of the Port in the world of commerce to-day. This

noteworthy industrial and commercial expansion was due mostly to two

factors, without whose aid it could not have taken place; the one was the

rise and development of banks, and the other was the Turnpike Road Act of

1751. The first of the great banking companies to open a branch in Leith

was the British Linen company, which, as its name indicates and as its

more recent note issues show, was first founded as a linen company, and

then forsook trading in linen to take up banking; but the Leith Banking

Company had already built and established itself in the neat little domed

building in Bernard Street, now occupied by the National Bank. It failed

in 1842, and had to close its doors. It was followed by the Edinburgh and

Leith Banking Company, a very wealthy corporation, now merged in the

Clydesdale Bank. Money was very scarce in Edinburgh and Leith in the

eighteenth century. To the credit system of these banks, by which Leith

merchants were able to finance their transactions, is largely due the

Position of the Port in the world of commerce to-day.

When we read in Macaulay’s

glowing pages of the adventures and mishaps of travellers like the

restless and gossipy Pepys while journeying along the wretched English

roads of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, we seldom realize that

the very same experiences were being met with on the sorry tracks that

passed for roads around Leith during the same period. When Sir John Foulis

and his friends drove in his great lumbering coach from Ravelston to the

horse-races on Leith Sands, they considered themselves lucky indeed if

they arrived home again without the carriage sticking fast in some hole,

or, worse still, breaking an axle. Axle-trees are frequent items of

expense in the old account books of the Laird of Ravelston.

When this old Scots laird

sent one of his estate carts to Leith, perhaps to the Vaults, to have the

wine cellar at Ravelston replenished, he had always to count upon so many

of the bottles being broken and their contents lost owing to the constant

jolts from holes and ruts. Thus in January 1700 four bottles of brandy out

of three dozen were lost in this way. Goods had accordingly to be carried

in small loads on the backs of horses, just as had been done in medieval

times. Trade could never expand so long as such conditions prevailed,

because each district had to be more or less self-sufficing, and provide

for its own needs. But all this was changed in 1751 by the Turnpike Road

Act, which, next to railways and the steam-engine, has done most to

promote Scotland’s trade.

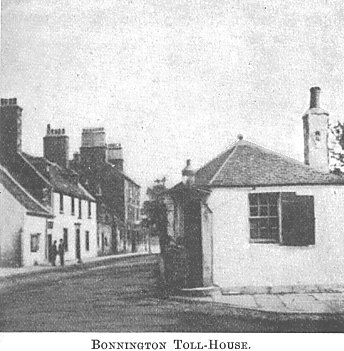

A

turnpike was a tollgate or tollbar set across a road to hold up carts and

carriages until the toll for the upkeep of the road was paid. From this

tax, what had before been impassable tracks now were made excellent!

roads, opening up communication with every district, and enabling carts

with many times the load of a pack-horse to pass along with ease. By the

Turnpike Road Act Leith’s trade area was largely extended, and this had

much to do with the wonderful expansion in her shipping trade in the

latter half of the eighteenth century. Let us illustrate this expansion

due to better roads by one example. In 1779 a Leith wholesale grocer, Mr.

Charles Cowan, carrying on business in the Tolbooth Wynd in the shop now

occupied by Messrs. Buchan and Johnston, removed to Penicuik, and began

papermakjng in mills which have since grown to be among the largest in the

world. Their export and import trade was done through Leith owing to the

improved roads, as it is so largely done to-day, and by the same means. A

turnpike was a tollgate or tollbar set across a road to hold up carts and

carriages until the toll for the upkeep of the road was paid. From this

tax, what had before been impassable tracks now were made excellent!

roads, opening up communication with every district, and enabling carts

with many times the load of a pack-horse to pass along with ease. By the

Turnpike Road Act Leith’s trade area was largely extended, and this had

much to do with the wonderful expansion in her shipping trade in the

latter half of the eighteenth century. Let us illustrate this expansion

due to better roads by one example. In 1779 a Leith wholesale grocer, Mr.

Charles Cowan, carrying on business in the Tolbooth Wynd in the shop now

occupied by Messrs. Buchan and Johnston, removed to Penicuik, and began

papermakjng in mills which have since grown to be among the largest in the

world. Their export and import trade was done through Leith owing to the

improved roads, as it is so largely done to-day, and by the same means.

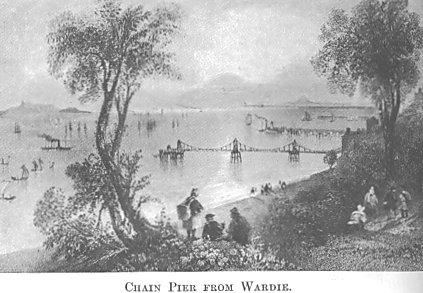

It

was only after the Turnpike Road Act came force that travelling began to

be common, because it could now be done with comparative ease and comfort.

Down to the middle of the eighteenth century, save an occasional coach to

London at long and irregular intervals, the only stage coaches in Scotland

were the two huge clumsy-looking vehicles that ran between Leith and

Edinburgh by the Easter Road. Stage coaches now began to travel regularly

on all the main roads, and, in connection with these, ferry and passenger

boats ran at regular and stated times to the various ports on the Forth,

from Leith and Newhaven, and later, when steam-packets came into use, from

the Chain Pier just beyond Newhaven, which was erected in 1821. With the

introduction of railways most of the steamers plying up and down the Forth

disappeared, and the ferry boats from Newhaven were transferred to Granton. It

was only after the Turnpike Road Act came force that travelling began to

be common, because it could now be done with comparative ease and comfort.

Down to the middle of the eighteenth century, save an occasional coach to

London at long and irregular intervals, the only stage coaches in Scotland

were the two huge clumsy-looking vehicles that ran between Leith and

Edinburgh by the Easter Road. Stage coaches now began to travel regularly

on all the main roads, and, in connection with these, ferry and passenger

boats ran at regular and stated times to the various ports on the Forth,

from Leith and Newhaven, and later, when steam-packets came into use, from

the Chain Pier just beyond Newhaven, which was erected in 1821. With the

introduction of railways most of the steamers plying up and down the Forth

disappeared, and the ferry boats from Newhaven were transferred to Granton.

Besides the stage coaches

supplying the needs of the passenger traffic on the Forth, there were the

royal mail coaches, which carried the mails as well as passengers. Many of

the coaches started from the Black Bull Hotel, Leith Street, a building in

which is now housed the confectionery establishment of Messrs. Duncan. In

the early decades of the nineteenth century, coaching’s primest age, it

was a brave sight, on a summer morning, to see the stage coach for Perth

and the North, with its four spanking horses, leave the Black Bull for the

ferry boat at Newhaven, the guard in red coat and beaver hat tooting

melodiously on his long horn as the horses set off down Leith Street.

Swinging round into Broughton Street, they were wont to go down the hill

in dashing style, the outside passengers steadying themselves by clutching

the guard irons as coach and horses careered down the steep descent

towards Newhaven.

But the days of the stage

coach were numbered. A rival was about to enter into competition with it

for the passenger traffic of the country. This was the locomotive engine.

While George Stephenson was constructing his Rocket, an ingenious

Leith residenter, Timothy Burstall by name, engineer at Leith Sawmills

above Junction Bridge, was building his engine, the Perseverance. Burstall

took the Perseverance to Manchester in 1829 to compete against

Stephenson’s Rocket for the prize of £500 offered by the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company. The Perseverance failed

to carry off the prize, but it was highly commended. Railways now began to

spread over the land. The Edinburgh, Leith, and Granton Railway was opened

in 1848, and the stage coach ere long became one of the things that had

been.

To the passenger traffic

from the Shore we owe the old Leith inns—the Britannia, the Old Ship,

and the New Ship. The Old Ship Hotel, built in 1676, was burned down in

1888, but was rebuilt, and is the only one of the three still open to-day.

The carved stones of the old building, together with its ancient sign,

adorn its present-day successor. It was in front of the "Old

Ship," as an inscription plate in the quay wall reminds us, that

George IV. landed in Scotland in 1822. The doorway of the New Ship Inn is

shown, exactly as it is to-day, in the old picture of the harbour in the

Trinity House.

Perhaps the most

fashionable Leith tavern during the latter half of the eighteenth century

was Straiton’s in the Kirkgate, opposite Laurie Street. The Kirkgate,

which we may call the High Street of Old Leith, was not then the

comparatively broad street it is to-day, but was still the narrow alley

the defensive needs of medieval times had made it. Its high-peaked gables

and numerous timber fronts jutting over the dingy booths or shops beneath

gave this street all that picturesque variety of outline so dear to our

forefathers

"Of the old days, and

the old ways,

And the world as it used to be."

Laurie Street was still

unbuilt. On its site grew a line of shady elms, while harvest-fields

stretched to the links, and on the south joined those of Quarryholes farm

and Pilrig. As it stood in close proximity to the Links, Straiton’s Inn

was a favourite resort of golfers. It was here, in all likelihood, that

the strange yet merry dinner and ball described in Smollett’s Humphry

Clinker were held.

Straiton’s always housed

a gay and aristocratic crowd during the week of the Edinburgh Race

Meeting. which was held annually on Leith Sands, then, strange as it may

seem, the most popular race-course in Scotland. These races are usually

said to date from the Restoration period, but Leith was noted both for

inns and horse-races centuries before then. In the Lord High Treasurer’s

accounts for the reign of James IV., entries like the following may be

read: "To the wife of the king’s inn, and to the boy that ran the

king’s horse at Leith, xxviii s." Sometimes this horse was King

James’s favourite steed, Grey Gretno. In 1816 the Race Meeting was

transferred to Musselburgh, where it has been held ever since.

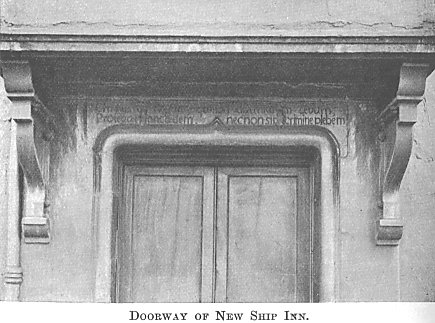

In

the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries much fancy was displayed in the

decoration of doorways when the rest of the building was left unadorned.

Several interesting specimens are to be found on the Shore. There is the

doorway to Mylne’s Land; another with a highly intricate monogram and

the date 1711 that must have given entrance to the King’s Wark; and the

doorway to the New Ship Inn. Over this doorway, in Latin, is inscribed a

verse from the 121st Psalm, most ingeniously adapted, by the alteration of

a word, to the calling of the house—" He that keepeth thee will not

slumber. Behold, he that keepeth the house shall neither slumber

nor sleep." The introduction of railways made Edinburgh the chief

place in our district for the arrival and departure of travellers, and

then the old-fashioned hostelries on the Shore were forsaken for the

palatial hotels that arose in Princes Street. In

the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries much fancy was displayed in the

decoration of doorways when the rest of the building was left unadorned.

Several interesting specimens are to be found on the Shore. There is the

doorway to Mylne’s Land; another with a highly intricate monogram and

the date 1711 that must have given entrance to the King’s Wark; and the

doorway to the New Ship Inn. Over this doorway, in Latin, is inscribed a

verse from the 121st Psalm, most ingeniously adapted, by the alteration of

a word, to the calling of the house—" He that keepeth thee will not

slumber. Behold, he that keepeth the house shall neither slumber

nor sleep." The introduction of railways made Edinburgh the chief

place in our district for the arrival and departure of travellers, and

then the old-fashioned hostelries on the Shore were forsaken for the

palatial hotels that arose in Princes Street.

For centuries, as has been

seen, Leith was the principal gateway into and out of the country. Within

the last century Glasgow has, of course, become the largest port in

Scotland. But while Glasgow has, almost mushroom-like, grown to be the

greatest Scottish port and the centre of the vast trade with the American

continent, Leith has

maintained its position as the principal channel for the trade and

commerce of this country and the northern parts of Ireland with the

various countries bordering the North Sea, as well as with the numerous

ports located on the Baltic and White Seas.

As has been seen, a great

increase in the traffic passing through Leith took place in the second

half of the eighteenth century. In 1763 the shore dues collected upon the

goods landed and shipped amounted to £580. Within twenty years this had

increased as nearly as possible sevenfold. The monetary value of the trade

of Leith in 1784 was estimated at £495,000, carried on by forty different

traders or companies. The more important commodities dealt in were grain,

flax, hemp, wood, tar, iron, and food-stuffs; while the manufactures

included ropes, canvas, soap, and candles. It is officially recorded

that in 1794 the number of vessels belonging to the Port of Leith was 144,

of an aggregate tonnage of 15,504, the men forming the crews numbering

854. Compared with the figures pertaining to more recent times these seem

insignificant. Thus the tonnage of Leith’s ships at the outbreak of the

Great War in 1914 was 254,082. And even these figures are far from

indicating the increase in Leith’s shipping facilities, for as each

steamship makes several voyages to every one of a sailing vessel the

latter figure ought to be multiplied six or even more times to give a true

comparison.

Up to the close of the eighteenth

century much of the commerce of Leith was conducted in brigs. These were

vessels of considerable size for those days, say from 160 to 200 tons

burden. The important and growing trade between the Thames and the Forth

was carried on by them. In some respects, however, they were not wholly

suitable for the business, and about 1790 a movement began to displace

them by rather smaller but handier craft called smacks. These soon

acquired wide renown, and proved so suitable for the conveyance of both

passengers and goods that within some twenty years there had been formed

to engage in the Leith and London trade four companies, which owned

between them twenty-seven fine vessels. One of these, the London and

Edinburgh Shipping Company, still carries on this service with admirable

energy, and, of course, with vessels of the most modern description. A

model of the Comet, a smack once owned by this Company, may be seen

within one of their office windows in Commercial Street.

Of these smacks and their

encounters with the French Privateers which then infested the North Sea in

large numbers, many stirring tales are told. For these were the days of

the Napoleonic wars, and even peaceful merchantmen were armed with

carronades—so called from being made at the Caron Ironworks—and their

crews were kept well drilled and ready to repel the attacks made upon

them. On one occasion in 1805 a privateer falling in with one of these

smacks, the Swallow, opened fire upon her, doubtless relying upon

an easy capture of a fairly valuable prize. For the result the Frenchmen

could hardly have been prepared, as the gallant Leithers replied with such

spirit and to so good effect that the enemy was fain to abandon the fight

and to thaw off in a crippled condition without having damaged the smack

in any way.

Such encounters as the Swallow

were of very common occurrence all through the wars of the eighteenth

century, and show the stuff of which Leith captains and mariners of those

times were made. But the Leith sailormen, in the long and strenuous fight

against Napoleon, did more than merely defend their ships when attacked.

In 1795 the ship captains of the Port, to the number of one hundred and

twenty, offered to serve their country at sea in any capacity suitable to

their position, while two hundred Newhaven fishermen manned the gunship Texel.

and, capturing the French frigate Neyden, returned to Newhaven

in triumph. As we shall see later, when occasion called, the same

indomitable courage was not lacking on the part of her modem sailormen in

the Great War.

To aid in the defence of

Leith if an attack should be made, the Martello Tower was built in 1809.

Leith Fort, upon which the chief burden of defence would have lain, had

been constructed in 1779 after the confusion and tenor of the threatened

attack on the Port by Paul Jones and his three warships. Happily no

occasion arose to test the efficiency of these works for the purpose for

which they were erected.

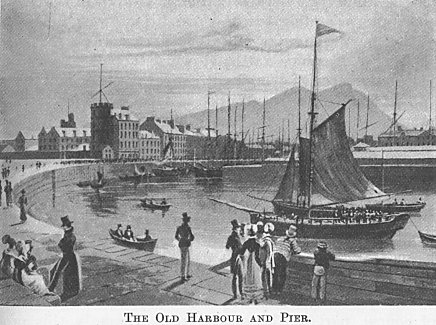

It

has already been mentioned that a large expansion of the trade and

commerce of the Port had been taking place for a considerable time prior

to 1800. Up till then Leith possessed no docks. The ships came into the

harbour and lay alongside the quay wall that lined the river bank. This,

as its shipping business extended, became more and more an intolerable

condition of affairs. It also suffered great inconvenience from the

existence of a bar at the harbour mouth, which confined to a comparatively

short period at the top of high-water of each tide the time during which

craft of any but the smallest size could enter or leave. The result was

that two wet docks were constructed on the west side of the harbour which

provided accommodation for about one hundred and fifty vessels of the size

then generally trading with Leith. It

has already been mentioned that a large expansion of the trade and

commerce of the Port had been taking place for a considerable time prior

to 1800. Up till then Leith possessed no docks. The ships came into the

harbour and lay alongside the quay wall that lined the river bank. This,

as its shipping business extended, became more and more an intolerable

condition of affairs. It also suffered great inconvenience from the

existence of a bar at the harbour mouth, which confined to a comparatively

short period at the top of high-water of each tide the time during which

craft of any but the smallest size could enter or leave. The result was

that two wet docks were constructed on the west side of the harbour which

provided accommodation for about one hundred and fifty vessels of the size

then generally trading with Leith.

This

work was begun in 1800, and, including two dry docks, was only completed

in 1817. The formation of these docks involved the destruction of an old

Leith landmark, a great rock even larger than the "Penny Bap" at

Seafield. This shell-covered rock, which lay on the sands just off the

Citadel, was known as Shellycoat, and according to the superstitious was

the haunt of a demon who wore a strange garment covered with shells, the

fearsome rattle of which appalled even the most courageous. The Leith boys

of older and more superstitious days looked upon it as a daring feat to

run round this rock three times, which they were wont to do with quivering

courage, repeating the challenge— This

work was begun in 1800, and, including two dry docks, was only completed

in 1817. The formation of these docks involved the destruction of an old

Leith landmark, a great rock even larger than the "Penny Bap" at

Seafield. This shell-covered rock, which lay on the sands just off the

Citadel, was known as Shellycoat, and according to the superstitious was

the haunt of a demon who wore a strange garment covered with shells, the

fearsome rattle of which appalled even the most courageous. The Leith boys

of older and more superstitious days looked upon it as a daring feat to

run round this rock three times, which they were wont to do with quivering

courage, repeating the challenge—

"Shelly-coat!

Shelly-coat! gang awa’ hame,

I cry na’ yer mercy, I fear na’ yer name."

They would then run for

their lives, fearful of being followed by Shelly-coat to punish them for

their defiance.

The dock plans included a

proposal for a large future extension towards Newhaven. This site, now

covered by the Caledonian Railway Station, was, at that time, of course,

part of the open Firth. Recently this proposal has been revived in a

somewhat different form, and authorized by Act of Parliament.

|