|

DURING the years of the

Commonwealth and the Protectorate, Leith was the headquarters of Cromwell’s

soldiers in Scotland. East and West Cromwell Streets in North Leith,

remind us to-day of this long occupation of the town by the English

troops, who, Puritans though they were, and therefore associated in our

minds with all that is grave and even sour-faced, were not indifferent to

the charms and virtues of Leith maids. South Leith Church records and the Mercurius

Politicus, the newspaper Cromwell’s men issued from the Citadel, and

the first to be printed in Scotland, show that many of them married and

settled in the town. Their skill and industry, added to the enterprise and

capital of English merchants who had been encouraged to start business in

the town, did much to promote the glass and linen trades established in

the Citadel after the Restoration.

During the nine years of

English rule Scotland had been better governed than ever she had been

under her own kings, but it was English rule, and military at that, and

the heavy taxation to which she was subjected to support the English

occupation had greatly impoverished the country and heavily handicapped

Leith’s trade. It was with delight, therefore, that the inhabitants beheld

the English garrisons march away from the Citadel to follow the

opportunist Monk to the south to bring about the Restoration, which was

celebrated in Leith with all the exuberant joy that marked that event else

where throughout the kingdom. The celebrations in Leith began with

thanksgiving services in the two parish churches. There was great ringing

of bells and flourish of trumpets, with bonfires in the streets and

fireworks in the Citadel till past midnight; for next to their religion

the Leith folk loved and reverenced their ancient line of Stuart kings.

The crown as a decorative

feature now became fashionable in honour of the return of the monarchy,

and as an emblem of loyalty was much used as an ornament on furniture,

especially on chairs. "Crown chairs" are still to be found in

old Scots mansions, and in the Picture Gallery at Holyrood at least half

the chairs are of this type and date from the Restoration period.

Little did the Leithers

foresee they were welcoming to the throne the worst and meanest king who

was ever to rule over them. If Cromwell had ruled them with rods, we shall

see Charles, even in Leith, ruling the people with scorpions. He soon

showed that no faith could be put in his plighted word. All he had

promised while wandering in Covenanting company in search of a throne he

now turned his back upon, and, by the most sternly repressive measures,

sought to crush the Church of Scotland out of existence.

The people of Leith were

soon to see this policy in action. Towards the end of December 1660 the

English warship Eagle, after a fortnight’s tempestuous voyage,

arrived in Leith Roads from London with a State prisoner of high rank

aboard in the person of Montrose’s enemy and rival, the Marquis of

Argyll, who had crowned

King Charles at Scone in 1650. He was received on the Shore by the water-bailie

and his deputy, attended by soldiers with displayed colours. Unlike the

great Montrose, he was "tenderly convoyed" towards Edinburgh,

and, of all who thronged the streets to see Argyll thus humiliated, none

showed him any disrespect. Basely betrayed by the unscrupulous Monk, he

was sent to his doom five months later.

The struggle against the

doctrine of the divine right of kings to do and rule as they pleased had

all to be fought over again. The majority in Leith, as elsewhere in

Scotland, chose the side of peace and immunity from persecution by

conforming outwardly, at least, to the arbitrary decrees enforcing the

Church policy of the Government. How untroubled and full of pleasure the

lives of such conformists could be, and how gay a place Leith was, even

during the torturings and violent deaths of the "killing time,"

we see from the account books of Sir John Foulis of Ravelston, the nephew

of the Ladie Pilrig, who supplied the heather for the smeekers during the

plague.

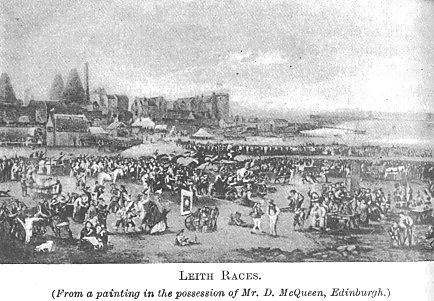

As

we read in Sir John’s pages of his visits to the annual horse races on

Leith Sands, of his golf matches on the Links, of his going to the play

(enacted in all probability in the tenths court at the King’s Wark), of

his dinners, and "sweeties" and oranges for the bairns at Mrs.

Kendall’s fashionable tavern in the Kirkgate, and of the refreshments at

Rob’s village inn at Restalrig, as they drove home in the great family

coach, we would never suspect that men were being hunted and shot down

among the hills and moors for no other crime than wishing to worship God

as their fathers had done. There is not the faintest reflection of such

things all through this record Sir John gives us of his daily life spent

in Edinburgh and at Ravelston during this period. and yet even in Leith,

while those who, like Sir John Foulis, conformed to the king’s policy in

Church matters could and did follow a life of pleasure, men resisted the

tyrannous measures of the king and were ready to risk all the penalties

the "Bluidy Mackenzie" and his deputy, Sir William Purves of

Abbeyhill, one of the elders in South Leith Church, might impose. As

we read in Sir John’s pages of his visits to the annual horse races on

Leith Sands, of his golf matches on the Links, of his going to the play

(enacted in all probability in the tenths court at the King’s Wark), of

his dinners, and "sweeties" and oranges for the bairns at Mrs.

Kendall’s fashionable tavern in the Kirkgate, and of the refreshments at

Rob’s village inn at Restalrig, as they drove home in the great family

coach, we would never suspect that men were being hunted and shot down

among the hills and moors for no other crime than wishing to worship God

as their fathers had done. There is not the faintest reflection of such

things all through this record Sir John gives us of his daily life spent

in Edinburgh and at Ravelston during this period. and yet even in Leith,

while those who, like Sir John Foulis, conformed to the king’s policy in

Church matters could and did follow a life of pleasure, men resisted the

tyrannous measures of the king and were ready to risk all the penalties

the "Bluidy Mackenzie" and his deputy, Sir William Purves of

Abbeyhill, one of the elders in South Leith Church, might impose.

Among the four hundred

ministers driven from their churches for holding that Christ and not King

Charles was head of the Church were the minister of North Leith, and Mr.

Hogg, the senior minister of South Leith, who escaped being imprisoned by

fleeing to Holland, where he spent the rest of his days as minister of a

Scots church in Rotterdam. The "outed" ministers began to preach

the Gospel in private houses, where many gathered to hear them. The

Conventicle Act declared such meetings illegal, and troops, quartered in

the town, went through the streets and closes every Sunday in search of

conventicles, and had their zeal in the work stimulated by the knowledge

that a Government reward of £50 would be paid for every one they

discovered.

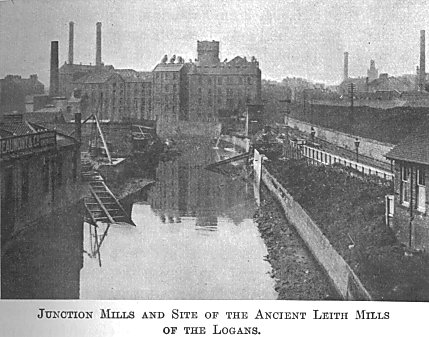

Millers

have always been noted, both in history and tradition, as stout and bold

men. Thomas Stark, the miller at Leith Mills, by the waterside opposite

Junction Road Station, was no exception to the rule. He was a stalwart

supporter of the Covenant. His brother-in-law was the outed minister of

Skirling. He went "afield," and held a conventicle, among other

places, at Leith Mills in February 1675, when the whole company were

arrested by a troop of soldiers under the command of Captain Ogilvie.

Fines up to £100 were imposed on each attender, for in those days of

corrupt courts of justice the Government depended on such sources for a

large part of its revenue. Despite increased efforts on the part of the

Privy Council to suppress them, the number of conventicles increased

rather than diminished, and even in Leith and Edinburgh, the headquarters

of the Government, it was found impossible to prevent the citizens from

attending illegal religious meetings. Increasingly stringent measures were

adopted to compel the people to attend the two parish churchs, but the

conventicles continued nevertheless. Millers

have always been noted, both in history and tradition, as stout and bold

men. Thomas Stark, the miller at Leith Mills, by the waterside opposite

Junction Road Station, was no exception to the rule. He was a stalwart

supporter of the Covenant. His brother-in-law was the outed minister of

Skirling. He went "afield," and held a conventicle, among other

places, at Leith Mills in February 1675, when the whole company were

arrested by a troop of soldiers under the command of Captain Ogilvie.

Fines up to £100 were imposed on each attender, for in those days of

corrupt courts of justice the Government depended on such sources for a

large part of its revenue. Despite increased efforts on the part of the

Privy Council to suppress them, the number of conventicles increased

rather than diminished, and even in Leith and Edinburgh, the headquarters

of the Government, it was found impossible to prevent the citizens from

attending illegal religious meetings. Increasingly stringent measures were

adopted to compel the people to attend the two parish churchs, but the

conventicles continued nevertheless.

Although none of the great

tragic events in this struggle between the king and his Scottish subjects

took place in Leith, yet the town was more or less incidentally associated

with several of them. The train-bands of Leith and Edinburgh were summoned

by tuck of drum to muster on Leith Links and then join Monmouth’s forces

against the Covenanters at Bothwell Bridge, when the incorporation of

carters and the "poor brewers" of Leith had their horses and

carts commandeered to form part of the baggage train. The prisoners

captured in the battle, after a weary journey, during which none dared

befriend them, were interned in the field then known as the Inner

Greyfriar Yard, of which the long narrow southern extension of the famous

churchyard, now known as the Covenanters’ Prison, formed only a small

part.

After having been confined

in their exposed prison for five months, two hundred and seven of the

Covenanters were marched to Leith and put aboard a sailing vessel called

the Crown, to be carried as slaves to the Plantations. There were

sore hearts and streaming eyes among the Leithers as they saw the crowd of

staunch but miserable Covenanters hustled through the street.

The captain of the Crown,

"a profane, cruel wretch," used them most barbarously, but

their sufferings were not to be for long. Their port was nearer than they

anticipated, for, as some one has finely said, their sails were set to

reach Jerusalem. On a dark and stormy night in December the ship, with her

living cargo under closed hatches, was dashed to pieces among the Orkneys,

and over two hundred of the wretched prisoners were drowned.

As the weary but undaunted

prisoners from the Inner Greyfriar Yard passed down the Easter Road to the

Shore of Leith, they might have noticed across the unenclosed fields, as

it swung in chains at the Gallow Lee—Leith’s place of execution for

all except pirates— part of the body of that once fearless fighter,

David Hackston of Rathillet, who held the bridge of Bothwell for hours

against the royalist troops, and who witnessed, but took no part in, the

foul murder of Archbishop Sharp on Magus Moor in 1679. To the Gallow Lee

many of the Covenanters were taken to their doom. It was a place of

execution less public than the Grassmarket, where the farewell speeches of

the martyrs deeply moved the crowds that came to see them done to death.

At the Gallow Lee the worst

criminals were hung, to add reproach and ignominy to their death. Here,

after Hackston’s remains had all been pecked away by the kites and

crows, five Covenanters were hanged. Their bodies were buried beneath the

gibbet, while their heads were spiked above the city gates. But good men

and true, among whom was the youthful James Renwick, the last of the

martyrs of the Covenant, came in the darkness and silence of night, dug up

the headless bodies, and reverently buried them in the West Kirkyard (St.

Cuthbert’s). They then boldly took down the

heads from the city gates; but, daylight overtaking them before they could

place these beside the bodies they buried them beneath two rose trees in a

garden near the present Royal Infirmary, where, forty-six years later,

they were accidentally discovered and reinterred in Greyfriars’

Churchyard beneath the Martyrs’ Monument.

From 1679 to 1682 James,

Duke of York, the king’s brother and heir to the throne, was much in

Scotland, where he seemed to divide his leisure between witnessing and

encouraging the cruelties of the torturing chamber and playing golf on

Leith Links, then one of the chief centres of the game. The Golfer’s

Land in the Canongate still survives to remind us of his match on the

Links with two English noblemen, when, partnered by John Paterson, a

member of a noted golfing family, he won the stakes and handed over the

money to his partner, who built with it the great tenement which he

decorated with his crest—a dexter hand grasping a golf club, with the

motto "Far and Sure."

From this time the

persecution became fiercer than ever, and nowhere outside the Netherlands

under Alva, could there have been a more complete system of tyranny than

that set up for stamping out Presbyterianism. The minister of North Leith,

a namesake of the great Reformer, was sent to the Bass Rock, then much

used as a State prison for confining outed and disobedient ministers. His

successor, like the two ministers of South Leith Church, was an

Episcopalian, which would seem to show that the majority of the Sessions

and parishioners of both churches, from choice or necessity, more probably

the latter, had conformed to Episcopacy. Among the Session members of

South Leith who favoured the policy of the king in Church affairs were

Lord Balmerino, whose action in doing so

was contrary to the traditions of his family, which had hitherto been

staunchly Presbyterian. Sir Patrick Nisbet of Craigentinny; Sir William

Purves of Abbeyhill, who, as assistant public prosecutor, had the odious

duty of assisting "Bluidy Mackenzie" in persecuting the

Covenanters; William Mylne, son of the King’s Master Mason; and Robert

Moubray, whose great ancestor, Sir Philip Moubray, held Stirling Castle

against Bruce, and whose last descendant in Leith, Mr. Robert Moubray,

banker, still remembered by many in the town for his courtliness of

manner, died in 1882.

Yet there were still those

in Leith who had not bowed the knee to Baal. Among the last to be

prosecuted for holding conventicles in the Port was Mr. William Wishart,

the outed minister of Kinneil, now the parish of Bo’ness. Mr. Wishart

was of the same family as the celebrated George Wishart, the famous martyr

of the Reformation period. After having suffered much persecution he had

taken up his residence in Leith, where, in 1683, he was seized by a party

of soldiers while conducting morning prayers in a private house. Though

"ane aged and infirm person, broken and disabled with many

diseases," he was cast into the Canongate Tolbooth, which, with its

picturesque turrets and projecting clock, forms so attractive an old-world

feature in the line of the Canongate to-day. He was sentenced to be

banished to the Plantations in the following year. He was, however,

conditionally set free under heavy sureties.

But the days of persecution

in Leith, as elsewhere in Scotland, were about to close. Charles II. died

in 1685. For a time after the succession of James II. the persecution was

continued with the utmost cruelty. Then, in 1687, in order to defeat the

penal laws against Roman Catholics, he issued his three letters of

Indulgence, allowing freedom of worship to all save those who persisted in

attending field conventicles. The outed ministers were now allowed to

preach in meeting-houses. In accordance with this "Liberty," as

the Leithers were accustomed to call the Declaration of Indulgence men

like Thomas Stark of Leith Mills and Robert Douglas of Coatfield (the most

enterprising among the Leith merchants of his time), who were still firm

in theft loyalty to the Covenant in North and South Leith, formed

themselves into a congregation and set up a meeting-house at the Sheriff

Brae, where service was conducted by the aged Mr. Wishart, the outed

minister of Kinneil, until a clergyman should be appointed.

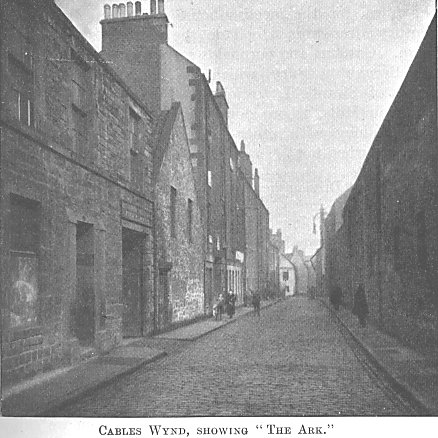

The "Liberty"

also set free Mr. John Knox from the Bass, who, later, was restored to his

charge in North Leith. The Sheriff Brae meeting-house proving too small, a

larger one, whose title-deeds name it "The Ark," was rented in

the Cables Wynd close by, and fitted up by Alexander Mathieson, whose

tombstone, until recently cast aside and neglected, has now, from its

association with the meeting-house, been placed for preservation within

the ground once set apart as a burial place for the clergy of South Leith

Church. Mr. Wishart continued to take the services in the meeting-house

until his son had completed his theological studies at Utrecht in Holland,

when he became minister to the meeting-house congregation.

On the exile of James II.

and the accession of William and Mary the Episcopalian clergy then became

"outed," and Mr. Wishart and the meeting-house congregation

returned to the old parish church in the Kirkgate. The long conflict

between Presbyterianism and Episcopacy came to an end, and the Church of

Scotland was established as it now exists. In later years Mr. Wishart was

appointed Principal of Edinburgh University. After David Lindsay he is the

most noted among the clergy who have ministered in South Leith.

The

old meeting-house still remains, but it is no longer associated with the

religious life of the town. Given over to commercial uses, it has for many

years formed a store for herring barrels in connection with the

fish-curing establishment of Messrs. Davidson and Pirrie in Cables Wynd,

where its east gable may be seen immediately adjoining the pend giving

entry to the narrow and gloomy alley designated Meeting-house Green. This

name not only keeps alive the memory of the old building as a place of

worship, but, at the same time, reminds us of the stretch of grassland

that lay between it and the town, for the meeting-house then, and for over

a century afterwards, stood on the very outskirts of the town. Gardens and

cornfields stretched from it towards the Broughton Burn, which ran in the

hollow to the south of Swanfield, to join the Water of Leith near Junction

Mills, where douce members of the meeting. house, along with other

Leithers of the seventeenth century, when not The

old meeting-house still remains, but it is no longer associated with the

religious life of the town. Given over to commercial uses, it has for many

years formed a store for herring barrels in connection with the

fish-curing establishment of Messrs. Davidson and Pirrie in Cables Wynd,

where its east gable may be seen immediately adjoining the pend giving

entry to the narrow and gloomy alley designated Meeting-house Green. This

name not only keeps alive the memory of the old building as a place of

worship, but, at the same time, reminds us of the stretch of grassland

that lay between it and the town, for the meeting-house then, and for over

a century afterwards, stood on the very outskirts of the town. Gardens and

cornfields stretched from it towards the Broughton Burn, which ran in the

hollow to the south of Swanfield, to join the Water of Leith near Junction

Mills, where douce members of the meeting. house, along with other

Leithers of the seventeenth century, when not

"Driving their baws

frae whins or tee"

at golf on the Links, were

wont to take a turn on the green at the "row-bowlis" at Bowling

Green, when they would forget for a time, in the excitement of the game

the troubles of religious strife and persecution.

Meeting-house Green is now

but an obscure and insignificant alley. Yet it bears one of the most

historic street names we possess, a name that should ever serve to remind

us that in the dark and troublous days of the "killing time" the

people of Leith did their part in opposing the tyranny of the Stuart rule

and in securing for those who came after them that freedom we enjoy

to-day. In resisting the oppressive measures of the Stuart kings, the

Leithers of those old and troubled times were fighting for something more

than the Covenant.

|