|

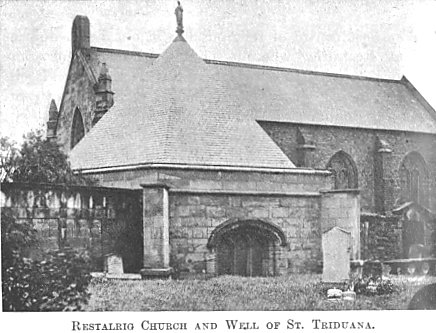

THE earliest centre of

religious life in our Leith district was at Restalrig, where a church or

chapel of some kind has existed from very remote times. Legend tells us

that among those who came to Scotland with St. Rule, the founder of the

first Christian church at St. Andrews, was St. Triduana, who had

consecrated herself to the service of God. To avoid the attentions of

Nectan, King of the Picts, who ruled from 706 to 732, and who greatly

admired the beauty of her eyes, the saint plucked them out and sent them

to him skewered on a thorn, after which she was allowed to live

unmolested, and spent the rest of her days in devotion and service at

Restalrig, where she is said to have died and been buried.

Her tomb, and holy well

adjacent, became the most noted places of pilgrimage in the Lothians, and

many reputed miracles were wrought by the beneficent influence of the

Blessed St. Triduana, especially on those deprived of sight or who were

afflicted with disease of the eyes. Through the offerings of the faithful

a chapel is said to have arisen over her grave, a little church, rude and

primitive in construction, after the manner of the ancient chapel now

uncovered within the foundations of the great Abbey Church of Holyrood.

We pass from the unstable

ground of legend to the sure foundations of history when we come to the De

Lestalrics and the Norman church they built at Restalrig before the days

of Alexander III. That church would consist of nave and chancel, and be

very similar to the Norman church at Duddingston built about the same time

(1143). This Norman church of the De Lestalrics became the parish church

of both Leith and Restairig, the latter place, strange as it may seem to

us to-day, being then the larger township of the two.

James III. and his talented

and brilliant son, James IV., were great lovers of architecture. They

rebuilt on a much larger scale the Church of Restalrig, which they did

their best to enrich and endow. One of these endowments was an annual

grant of £28, payable from the rents of the King’s Wark on the Shore.

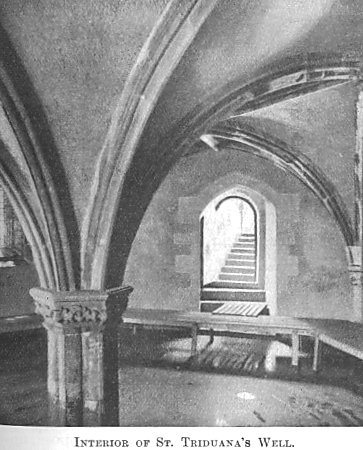

During the same period a chapel was built, or more probably rebuilt,

enclosing the well below it under beautiful Gothic stonework, which still

remains. The chapel, which formed the upper story, was destroyed at the

Reformation, and the well filled up as a monument of idolatry. This well

of St. Triduana and that of St. Margaret, which once stood within a few

hundred yards of it in the Clockmill Lane, are the two most

architecturally beautiful wells in Scotland. St. Margaret’s has been

removed to the King’s Park, though it has left its name behind it to the

North British Railway works which displaced it.

The well of St. Triduana has been cleaned

out and restored. The chapel that once stood above it, enclosing her

shrine, has not as yet been rebuilt, but an effigy in stone of the once

far-famed St. Triduana,

"Quhilk on ane thorn

has baith her ene,"

surmounts the apex of the well, just as her

image in the days of the old faith stood above the altar in her chapel.

A stirring and busy place must Restalrig

have been in pre-Reformation times, when so many simple and devout souls,

rich as well as poor, came to seek healing for their bodies and salvation

for their souls at the well and shrine of St. Triduana, and went away

consoled and full of hope that by the powerful intercession of the blessed

saint their desires would be fulfilled. To this mediaeval parish church at

Restairig, too, went the people of Leith on Sundays, and especially on

holy days, which they dearly loved because of the freedom they brought

from the dull and monotonous routine of their daily toil. But the

inconvenient distance which separated the Leithers and their parish church

at Restalrig, in those days when the church was more closely associated

with the everyday life of the people than it is now, made them resolve to

have a church nearer home, within Leith itself.

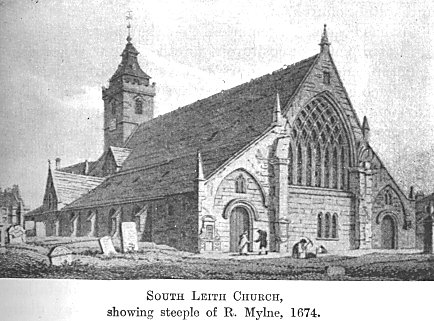

This church, familiar to us

all to-day as South Leith Church, was, like the one at Restalrig,

dedicated to the Virgin Mary, who thus became the patron saint of the

community, and took the chief place in the town arms. That is why in older

days it was often called St. Mary’s and oftener still, "Our Lady

Kirk" of Leith, as if it had a very warm place in their hearts. And,

indeed, it might well have, for it gave them their great annual holiday. A

great time of rejoicing in all Catholic countries to-day, as in days gone

by, is the 15th of August, when all make holiday because

The blessed Virgin

Marie’s feast,

Hath then his place and time,"

for on that day, according

to Catholic belief, the Holy Virgin was miraculously taken up into heaven,

as depicted in Rubens’s great picture at Antwerp.

But our old Catholic

forbears in pre-Reformation Leith had a double cause for rejoicing on that

day. The 15th of August was not only the Festival of the Virgin, but also

the feast day of their patron saint. Are not the town arms to-day a quaint

old-world galley, in which the Virgin sits enthroned under a canopy with

the Holy Child? As in Edinburgh on St. Giles’ Day, all the trade guilds

in the town, headed by the priests of St. Mary’s, went in procession,

bearing the image of the Virgin decked in jewels and costly raiment before

them. All the members of the family who worked elsewhere endeavoured to

pass the day among their own people, with whom they spent a joyful evening

over pancakes and other dainties, telling "geists," or stories,

round the family hearth.

Strange as it may seem, we

have no record as to who were the founders of St. Mary’s Church, nor

do we know exactly the date of its erection; but neither is difficult to

guess. We have seen how the good folk of Leith, shut out from being

merchants, became mariners and shipowners, like Sir Andrew Wood and the

Bartons, bringing much wealth to the town. Under the peaceful and ordered

government of James IV., and the encouragement he gave to Leith sailormen

and shipping, the town advanced rapidly in wealth, and was more prosperous

during his reign than at any succeeding period

until after the Union of 1707. James IV., like

his father, was also a great lover of building, and the growing wealth of

the town made their reigns a noted building epoch in our neighbourhood. In

James III’s time the masons and wrights of Edinburgh had become so

important that they had been incorporated as a guild by the Town Council,

and had had assigned to them the aisle and altar of St. John the

Evangelist, now the Montrose Aisle, in St. Giles’ Church. Cochrane, the

king’s Master Mason, a man of outstanding ability as an architect, had

been hanged at Lauder Bridge; but he was succeeded in his post by John

Milne, the first of a talented family of royal masons, whom we shall see

doing much building work in Leith that still survives in our midst.

We have the wealth and

prosperity of Leith at this period reflected in the building of the

Collegiate Church of Restalrig, the erection of the bridge and chapel of

St. Ninian, and now in the founding of the great Church of St. Mary in the

Kirkgate, and all within a few years of one another. St. Mary’s was

erected before 1490, and is therefore in the ornate style of architecture

known as Decorated Gothic, which was in fashion in Scotland during the

fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Beautiful traceried windows are the

most noticeable characteristic of the Decorated style. The two finest in

South Leith Church to-day are the east and west windows, but they are

modern. The stonework of their predecessors was removed by the restorers

of 1847. That the west window had looked down on many an historic scene,

enacted both within and without the old church, mattered nothing to them.

It now forms a much-prized decorative feature of a church by the shores of

Loch Awe. Nothing could better show with what heedless and irreverent

spirit those who restored South Leith in 1847 went about their work.

South Leith Church has also

suffered much in past centuries from the rude hand of war. What survives

to-day is only a fragment of a noble cruciform church, once as large,

though not so broad, as St. Giles’ is today. Only the nave of this great

church remains to us now. The choir and transepts, with the central tower,

were ruined by the guns of the English in 1560. Two of the four great

pillars that once supported the tower may be seen from within the church,

forming part of the east wall of the nave. Before the restoration in 1847

these were also visible from the outside, as old prints show.

In pre-Reformation times

the upkeep and reparation of the church fabric was divided between the

clergy and the people, the clergy maintaining the choir where they alone

worshipped, while the people upheld the nave. In the simple ritual of our

Presbyterian form of worship the choir was not needed, and was generally

allowed to fall into ruin. The choir and transepts of South Leith Church,

therefore, after being ruined by the cannon of the English during the

siege of 1560, when a cannon-ball passed right through the building from

east to west during the celebration of Mass, were never rebuilt. Still,

what remains forms a beautiful and stately church.

It has been often remarked

that the pillars of the nave are not directly opposite one another. But

this feature is not peculiar to St. Mary’s, for similar irregularity in

the placing of the pillars may be noticed in St. Giles’. This may have

arisen from careless measurement, but is more probably due to some

difficulty of site. Parts of the foundations of choir and transepts still

exist beneath the soil of the churchyard.

The ruins, as at Restairig,

became a convenient and ready quarry from which to obtain building

material. Carved and moulded stones, and even portions of sculptured

memorial tablets, have been found in demolishing the walls of old houses

in and about the neighbourhood of the Kirkgate, for our pre-Reformation

forefathers, like the later church restorers, were in no way distinguished

for their veneration for things sacred.

The earliest notice we have

of St. Mary’s Church is in 1490, when Peter Falconer gifted the annual

rent of a house in "the Lees," the district in and around

Yard-heads School and Henderson Gardens, for the maintenance of the

chaplain of St. Peter’s Altar in the new Church of the Blessed Virgin

Mary in Leith. A few years later, in 1499, Gilbert Edmonston similarly

endowed the Altar of St. Barbara. Peter Falconer and Gilbert Edmonston

were two of the best known of Leith’s sea captains at this period. Peter

Falconer was a man of wealth, as many of Leith’s shipmasters at that

time were. He had sailed much in northern seas. For that reason, when the

uncle of the King of Denmark came to visit the Scottish Court, James IV.

lodged him in the house of Peter Falconer in Leith. St. Peter’s and St.

Barbara’s were only two of many altars in this once large and beautiful

church.

The high altar in honour of

the Virgin Mary stood at the east end of the choir, with a beautiful

statue of Our Lady standing above it. In front hung an oil lamp, always

alight night and day, in honour of the sacramental bread or host, which,

enclosed in its jewelled pyx, was suspended just over the altar. The

upkeep of this lamp was in all likelihood provided for by the rent of the

Lamp Acre at Seafield. This piece of ground lay adjacent to lands

belonging to the Lamb family, who had been dwellers in Leith from the days

of Bruce, and may have been gifted by one of them for the welfare of the

souls of his parents and of his own.

The church door giving

access to the high altar was never closed, so that the faithful might come

to worship there at any hour of day or night. Opposite this Gothic

doorway, in the churchyard wall, was a wicket, perhaps originally simply a

stile, as it was named The Mid-style, leading out to Coatfield and

Charlotte Lanes, which, before Lord Balmerino extended his garden to the

Links, formed one continuous street with Quality Street, and was known as

the Road to the Altar-stane.

The aisles still remain in

South Leith Church, but the chantry chapels, with their altars between the

pillars, are gone. A chantry chapel was simply a part of a church screened

off, before whose altar Masses were sung for the good estate of the

founder who endowed it and other persons named by him, and for the good of

their souls after death. Such endowed services were known as chantries,

and were intended to continue until "the day of doom."

Now, after reading about

those various chantry chapels and their pious donors, we need not lament

that the founders of this once great and still beautiful Lady Kirk of

Leith are unknown to us. They are well known to all of us, not as

individuals, save a few exceptions, but in the mass, for they were the

people of Leith themselves, chiefly through their trade guilds, which,

like that of the cordwainers or shoemakers, had each its altar and chapel

in the church. As we have learned before, the promoting and maintaining of

religious services at the altars of their patron saints would seem to have

been one of the chief purposes of these old guilds.

Sir John Logan, in

accordance with the family tradition of loyalty and devotion to the

Church, must have given the site and the churchyard, and his uncle of the

Sheriff Brae and his cousins of Coatfield would lend a helping hand. The

parson of the Church of Restalrig, without whose sanction no daughter

church could have been founded in the parish, gave his blessing and his

prayers. Indeed all, rich and poor alike, shared enthusiastically in the

work, for it was to bring the benefits of religion to their very doors.

The sound of its bell, as it rang out for the various daily services,

would be for them, as some one has said, a sweet and holy melody, for it

would enable those within reach of its sound to join in spirit in the act

of worship being offered in God’s house.

As most of the inhabitants

of the town belonged to one or other of the various guilds, the members of

each, by means of their guild chapels, came to have their own part of the

nave for worship and for burial. These various chapels, with all their

rich adornment, were swept away at the Reformation, but we have neither

record nor tradition of the change. Then, too, it was decreed that the

people of Restalrig were to repair to the Church of South Leith, which in

1609, by an Act of the Scots Parliament, became the place of worship for

the parish. It was further decreed that the Church of Restalrig as "a

monument of idolatry be utterly casten doun," and soon little more

than the choir of this once famous church was left standing. The

shrine of St. Triduana was destroyed at the same time, and her holy well,

to which devotees thronged in pilgrimage "to mend thare ene,"

was filled up. Yet even to this day people sometimes wander to Restalrig,

who still have faith in the healing virtues of the Holy Well of St.

Triduana.

At the Reformation the Rev.

David Lindsay, the friend of Knox, and one of the most noted of the

Reformers, became the first Protestant minister of St. Mary’s. He was

designated parson of Restalrig and minister of South Leith. The chapels

and altars of the old craft guilds went from the church with the old

Catholic faith. Under the name of trade incorporations, however, these

guilds were still closely associated with the work of the church. It was

they who paid the stipend of the second minister in the days when the

church had two. They were largely responsible for its upkeep and

maintenance, for to them and the other parishioners the church had been

bequeathed by the Golden Charter of James VI. in 1614, together with the

churchyard, the lands of the Hospital of St. Anthony, the Chapel of St.

James at Newhaven, and such other properties as the Lamp Acre at Seafield

and the Holy Blood Acre at Annfield. But the lands of Parsonsgreen, which

once formed the greater part of the glebe of the parson of Restalrig, as

the name would lead us to suppose, now became the patrimony of the Logans

of Parson’s Knowes, as these lands were called in the old

pre-Reformation times.

After the disastrous

overthrow of the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar Leith was occupied by

Cromwell’s troops, when the church was forcibly taken from the

parishioners and, with the churchyard, was turned into a depot for

military stores. Pews were just then coming into fashion, and those that

had up to this time been placed in the church were used by the Ironsides

for firewood. The people of South Leith had now to go to Restalrig for

worship, just as their fathers had done before them; and save for a few

months in 1655, when they were again allowed to use the church, they held

their services around the ruins of the ancient village church at Restalrig

until 1657, a period of seven years. At that date the English garrison and

their military stores were removed to the newly built Citadel, when South

Leith Church was once more opened for worship to the great joy of the

parishioners.

From just before the days

of Cromwell, as we have already seen, pews began to be placed in the

church, and this was done in a way that is highly interesting and

instructive. Each trade incorporation had its pews placed just where the

guild altar had been situated in olden days, and round which its members

had worshipped. Their galleries and pews were adorned with the heraldic

emblems of the craft. Some of these have been restored in recent years,

and show us how the sittings in the church were apportioned among the

various incorporations. The gallery or loft of the Trinity House was at

the east end of the church, while that of the maltmen was at the west end

and now forms the choir and organ loft. On the floor beneath this gallery

some tombs of the maltmen’s incorporation have escaped the destroying

hand of the so-called church restorer. The north side of the nave was

occupied chiefly by the hammermen, shoemakers, and porters, while the

south side was given up to the merchants and traffickers. The trade

incorporations still continued to bury their dead where their chantry

chapels had stood in the old Catholic days. It is plain, however, that

they could not go on doing so in the limited space within the church. So

in the middle of the seventeenth century this custom was departed from,

save in the case of a few distinguished persons. It now became general for

all to be buried in the churchyard, which was divided off in a way that

forms an instructive example of how much the customs of past days still

influence the present. Each trade guild had, as a burial-place, that part

of the churchyard allotted to it adjacent to its sittings within the

church, where in ancient days the guild altar had stood and before which

its members had been buried.

Beyond the churchyard wall

runs one of the main thoroughfares, which had been named Constitution

Street from the zealous opposition of the townsfolk to Roman Catholic

Emancipation, against which all the churches and trade incorporations of

Leith had petitioned again and again. And yet, all the time, the location

of their sittings within the church, and of their burial-places in the

churchyard without, had been determined by the religious customs of their

old Catholic forefathers. Truly we Leithers are a contradictory people.

The parish churches and

churchyards of Leith and Restalrig are so full of interest that they would

require a book to themselves. Within the limited space of a single chapter

one cannot do more than briefly notice a few of the more outstanding

features of interest associated with them. The ringing of the church bell

each night and morning is another instance of a custom being continued

long after it has outlived the purpose for which it was instituted. It

shows us that in earlier days the Church regulated the hours of labour as

well as the morals of the people—days when clocks and watches were so

expensive that only the rich could purchase them. But in pre-Reformation

days this bell was more than a mere factory bell: it was the Angelus, that

summoned its hearers to matins and vespers that they might begin and end

each day’s labour with an act of worship. Let us hope that this bell

will long continue to ring, for, though it may have little meaning and

purpose now, still it is one more link between our time and the pious days

of yore. For long after the Reformation North Leith rang its bell at 10

p.m., while South Leith sent round the town drum at the same hour to warn

all people within doors. "Elders’ hours" had to be observed in

old-time Leith.

The great iron guards

erected to protect the graves against the nefarious violations of the

Resurrectionists form a striking feature along the north wall of South

Leith Churchyard, and are very noticeable in Restalrig. They all date from

before 1832, in which year the Anatomy Act, by allowing medical schools to

acquire subjects for dissection in a legal way, put an end to the trade of

the Resurrectionists.

In both churchyards may be

seen excellent specimens of tombstones, especially those of cordwainers

and hammermen, adorned with the heraldic emblems of the trade of those

whom they commemorate, and showing the pride of the old craftsmen in being

members of the incorporation of their craft. A much weather-worn tomb of a

hammerman in Restalrig not only shows the heraldic emblems of the craft,

"the hammer aneath the croon," but also the trade motto,

"By hammer and hand all arts do stand." Near the centre of the

churchyard is one showing the cordwainer’s emblems, "the cutting

knife aneath the croon," while over the top is the following couplet

"The life of man’s a tolling

stone,

Moved to and ho, and quicklie gone."

Among the noted tombs in Restalrig

Churchyard are those of General Rickson, the companion of General Wolfe,

the hero of Quebec; Lord Brougham’s father; Louis Cauvin; Lang Sandy

Wood, the famous surgeon of Sir Walter Scott’s time; and that eccentric

creature, Henry Prentice, who set up his own tombstone in the Canongate

Churchyard,

and inscribed upon it part of his epitaph, which his friends, if he had

any, never completed. The boys of the Canongate making it a target for

stones, as its chipped surface still shows, he had it removed to Restalrig,

and was eventually buried beneath it.

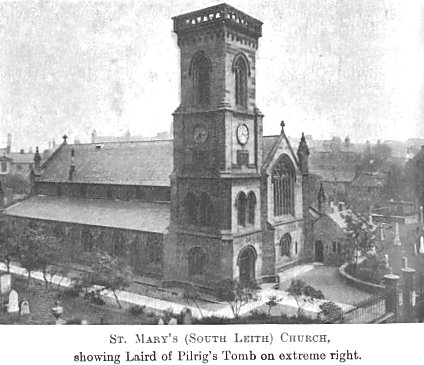

St. Mary’s Churchyard is the Greyfriars’ of

Leith. Crowded within its narrow limits lie generation after generation

of its inhabitants. Round its walls are the stately monuments of her

merchant princes. In the portion of the churchyard set apart in days of

old for the "Gentlemen Traffickers" lies one whose name the

genius of Robert Louis Stevenson has made familiar wherever the English

language is spoken, the Laird of Pilrig to whom be brings his hero,

David Balfour, in the opening chapters of Catriona’. Opposites

on the walls of the church, is the memorial stone of John Home, the

author of Douglas. To the east of these is a fine monumental

stone to the memory of Robert Gilfillan, who wrote the beautiful song,

"O, why left I my hame?"—a song which has touched the

hearts of so many Scots exiles, and among them that of the gifted author

of Catriona".

And last, in the portion of ground at the east end

of the church allotted to the mariners, is the handsome tomb of that fine

old Leith salt, as was his father before him, Captain Robert Duncan, who was born in

Water Street, and who rose to be Commodore of the Union-Castle Line of

Mail Steamers. Always a favourite with passengers, and, like Tom Bowling,

"the darling of his crew,"

"He never from his word

departed,

His heart was kind and soft,

Faithful below he did his duty,

And now he’s gone aloft."

He was a generous friend to

the boys and girls of Leith. many of whom, now grown-ups, must have happy

memories of the annual picnic to Aberdour he provided for their pleasure

under the charge of Mr. Thomas Fraser, then of Yardheads School.

In 1847—8 South Leith

Church had the misfortune to undergo what is called

"restoration." That means that it was shorn of all its ancient

features, and made to look as new and up-to-date as possible. The old

porch was removed, but its position is marked, by a label or stone

moulding on the north side of the church tower, while a similar moulding

on the gable facing the Kirkgate marks the site of the old west door,

which, however, was not used. The walls had been covered with memorial

tablets to those who lay beneath just as in the days before the

Reformation. These were all removed, and the tombstones in the floor, many

of them of beautiful workmanship, were used to pave the vestibules and

stair landings leading to the galleries, where they may still be seen

divided and mutilated to fit them in position. The oldest, bearing the

date 1593, is to one of the Logans, probably of Coatfield.

The Kirkgate gateway marks

the site of the old entrance porch, which contained several chambers and

was called by its old pre-Reformation name of the Cantore or Song School,

where the boys were trained to sing in the church choir. Attached to the

walls of the Cantore were the "jougs" which now hang in the

church porch within the tower. As in St. Giles’, the outside stonework

is new, but much of the interior is old, and has been consecrated by the

prayers of the many generations of Leithers who worshipped here ere

"They wan their rest,

The. lownest and the best,

I’ the auld kirkyaird when a’ was dune."

|