|

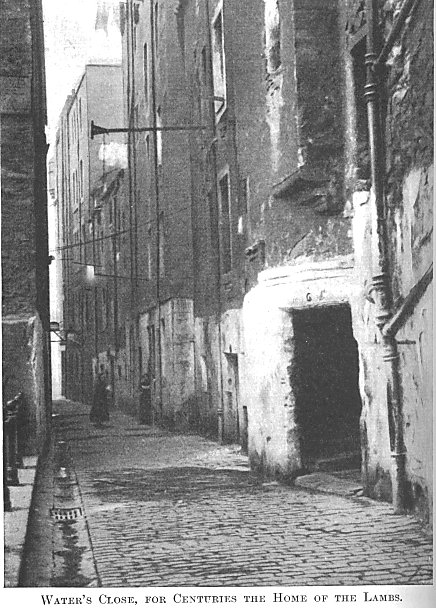

In the days when

James I became king, Leith had really hardly attained to the dignity of

being called a town. The population at this time could not have exceeded

if it even reached, fifteen hundred. But even in those days Leith was ever

extending its bounds. At the beginning of the reign the street known from

time immemorial as the Shore did not extend farther than the Broad Wynd.

On the stretch of rough waste land beyond this, covered with sand and

coarse grass, James I. built his King’s Wark, which occupied all the

ground between Broad Wynd and Bernard Street.

While the King’s

Wark was extending the Shore seawards, another group of buildings, whose

character and purpose were very different, began to rise among the fields

and meadows to the south, near where the lands of the Logans met those of

the Monypennys of Pilrig. This was the Hospital of St. Anthony, which,

unlike the King’s Wark, has left its own memorial behind it in the form

of some of the oldest and most familiar place-names in the town. All

wanderers in and about the Kirkgate know the St. Anthon district with its’

several old-time alleys-—they can hardly be dignified as streets—to

which the

famous hermit saint has given his name. The Hospital of St. Anthony was

founded in 1430 by the first of the

Logans to own the lands of Restalrig - Sir Robert, who had married the

Lady Katharine, as their family tree designates her, the daughter and

heiress of Sir John de Lestalric who died in 1382. Sir Robert was now

grown old in years. His life had no doubt been wild and turbulent, as was

the age in which he lived, but it had not been unaffected by the softening

influences of the Gospel and the teaching of the Church. He was religions

according to his lights, and now in his old age, when no longer able to

pursue the old strenuous life, his thoughts turned more and more to his

duty to God and his fellow-men. The religious zeal and enthusiasm which

had founded and built the great abbeys of the twelfth and thirteenth

centuries had now spent itself, and yet devotion to Mother Church and her

teaching was more widespread among the people of Logan’s time than ever

before.

In those centuries

men believed with the "gudewife" of their own age who taught her

daughter that,

"Meikle grace

comis

of praying

And brings men aye to

good ending,"

and, acting on this

belief, men sought to secure their own salvation and that of their

relations by endowing the Church according to their means, and conferring

such benefits and blessings on those who were in need, that both the

Church and succeeding generations of recipients of their benefactions

would daily remember them in their prayers. And for these reasons Sir

Robert Logan founded the Hospital of St. Anthony, which stood where the

Trafalgar Hall and the Kirkgate United Free Church stand in St. Anthony

Lane today. All that now survives of this ancient religious house are its

name (given to the district in which it once stood), its seal (now in the

Antiquarian Museum), a fragment of its records entitled

"Rentale Buke of Sanct Anthoni’s and Newhavin," written by men

who were no great scholars, and a few charters, which, like so many of

their kind, add little to our knowledge.

In those charters the

institution is sometimes designated the hospital and sometimes the

preceptory of "the blessed Confessor

Saint Anthony, near Leith "—always near, never in, Leith,

showing that the St. Anthony district was at this date outside the

town.

Hardly anything is known of

its history beyond what is told us in the "Rentale Buke." Here

we read of its foundation by Sir Robert Logan in the reign of James I.,

and of the names of some of its benefactors, few of whom are otherwise known to us. No

picture or description of the arrangement of its buildings has come down

to us, and, to add to our perplexity, this institution has been called

indiscriminately a monastery, an abbey, a preceptory, and a hospital. It

was neither an abbey nor a monastery, for the Logans had neither the

means to build nor to endow such a religious house, but the

establishment of smaller religions houses called hospitals now came into

fashion as a common work of Christian charity. Such institutions help us

to see how widespread was Christian activity in these old Catholic

times, and how the poor and needy were cared for in pre-Reformation

days. They were sometimes called Maisons Dieu, or houses of God. A

hospital was indeed a house of God, for therein Christ was received in

the person of the needy in obedience to His own words, "I was a

stranger and ye took Me in." As Spenser tells us in his Faerie

Queene,

"Their gates to all

were open evermore,

That by the wearie way were travelling;

And one sat

wayting ever them before,

To call in commers-by that needy were and poore."

The Hospital of St. Anthony

in Leith served more especially as a home for the aged and infirm, and

especially of those who had in any way been its benefactors. In the

arrangement of their buildings and in the life lived in them, hospitals

closely resembled the larger religious houses such as Holyrood. Like

Holyrood, too, St. Anthony’s Hospital was possessed by Augustinjan

canons, but of a particular order known as the Canons Regular of St.

Anthony. Their special duty was to wait on the sick, the aged, and the

poor. They wore the same black habit as the brethren of Holyrood, but were

distinguished from them by a blue cross, shaped like the letter T, on the

left breast, which you may see on the accompanying picture of the seal of

the Hospital. Around this seal is the legend, "S Comune Preceptorie

Sancti Anthonii Prope Leicht," which means, "The Common Seal of

the Preceptory of St. Anthony, near Leith." There also you see the

figure of St. Anthony in a hermit’s gown under a canopy, with a book in

one hand and a staff in the other. At his right foot is a pig with a bell

fastened to its neck, and over his head is the T-shaped cross. An old

Scots poet, Sir David Lindsay, refers to the gruntil of St. Anthony’s

sow, The Hospital of St. Anthony

in Leith served more especially as a home for the aged and infirm, and

especially of those who had in any way been its benefactors. In the

arrangement of their buildings and in the life lived in them, hospitals

closely resembled the larger religious houses such as Holyrood. Like

Holyrood, too, St. Anthony’s Hospital was possessed by Augustinjan

canons, but of a particular order known as the Canons Regular of St.

Anthony. Their special duty was to wait on the sick, the aged, and the

poor. They wore the same black habit as the brethren of Holyrood, but were

distinguished from them by a blue cross, shaped like the letter T, on the

left breast, which you may see on the accompanying picture of the seal of

the Hospital. Around this seal is the legend, "S Comune Preceptorie

Sancti Anthonii Prope Leicht," which means, "The Common Seal of

the Preceptory of St. Anthony, near Leith." There also you see the

figure of St. Anthony in a hermit’s gown under a canopy, with a book in

one hand and a staff in the other. At his right foot is a pig with a bell

fastened to its neck, and over his head is the T-shaped cross. An old

Scots poet, Sir David Lindsay, refers to the gruntil of St. Anthony’s

sow,

"Quhilk bore his holy

bell."

Though every vestige of the

Hospital of St. Anthony has long years ago disappeared, and no memory of

the benevolent work it once carried on has come

down to us, yet no institution of Old Leith, as has already been said, has

left so many memorials behind it in the form of

place-names. From what we know of mediaeval hospitals in England, such as that

of St. Cross, near Winchester where wayfarers may still

difficult to picture to

ourselves as they once stood the buildings of St. Anthony’s Hospital.

These consisted of two parts—the domestic

buildings, or hospital proper (containing the refectory, or dining-hail,

and the dormitories or sleeping-rooms), and the chapel, for it must never

be forgotten that the mediaeval hospitals were first and foremost religious

institutions, and in the very closest association with the Church. The

domestic buildings stood on the west side of St. Anthony’s Lane, and

stretched towards Henderson Street and the Yardheads. This latter street

takes its name from the great gardens and orchards of the canons which

extended westwards towards the Water of Leith. Yard and garden are simply

different forms of the same word.

These gardens, safe from

intrusion like the Hospital itself behind their great enclosing wail,

were a veritable haven of rest to the aged and infirm who were

privileged to enjoy the hospitality of the canons of St. Anthony, and

here, amid the old Scots flowers, the shady trees, and the perfume-laden

air, they lived out the evening of their days. No dormitory of the

Hospital, we may be sure, would ever be long vacant, but few names of

these inmates and pensioners have been recorded. The canons would have

outdoor as well as indoor patients, and no garb was more familiar in the

streets of Old Leith than the black habit with the blue cross of the

canons of St. Anthony as they passed along on their errands of mercy.

But the great centre of

the life of the Hospital was its church or chapel. This building, if

tradition speaks true, seems to have been unusually large, with either a

central or a western tower. It had several altars. The high altar in the

chancel was, of course, dedicated to St. Anthony, and there were,

besides, altars to the Blessed Virgin, Mary Magdalene, and St.

Catherine. Perhaps the last was a loving benefaction of Sir Robert Logan, the founder, in memory of his wife,

Katharine de Lestalric. In the chapel, as the Angelus bell rang out for matins or for

vespers, all the inmates would gather for worship. This church, in

accordance with use and wont, would be at the east end of the Hospital buildings, and would stand east and west—that is,

in the same direction as South Leith Parish Church—so that the east end of the choir would just be adjacent to the line of the

Kirkgate between St. Anthony and Giles Streets.

The churchyard lay immediately

to the south of the church, in accordance with the invariable custom in

pre-Reformation days, when the shadow of the church cast by the sun was never allowed to fall over the graves of those

who had found theft last resting-place around its walls. This custom has also been

observed in South Leith Church, for the part of its surrounding graveyard lying on the cold north side is a

post-Reformation addition.

In founding this Church of St. Anthony, Sir

Robert Logan for once laid the people of Leith, and

especially the old and weak, under a peculiarly deep debt of gratitude,

since their nearest place of worship until it was built had been their

parish church of Restalrig. St. Anthony’s was, no doubt, the church of

the canons and inmates of a private institution, but in such religious

institutions in mediaeval times the general public were allowed to

worship in the nave of the church in return for alms bestowed on the

hospital. Judging from the many human remains laid bare when digging

operations are in progress in St. Anthony Street, the cemetery of the

canons of St. Anthony was used by others besides the occupants of the

Hospital.

This could only be done by special arrangement with

the parson of Restalrig, the parish priest, part

of whose income came from the baptismal, marriage, and burial

pennies of the parishioners. These fees they would continue to pay,

in addition to their alms to the good canons of St. Anthony’s for

the privilege of worshipping in their church and burying within

their churchyard. In those days of simple faith the privilege of

having a church in their midst was

prized in a way we are forgetting to understand, or even to

appreciate, and at daybreak, at noon, and at the curfew hour, when

the Angelus or "Gabriel bell" pealed forth from St.

Anthony’s tower over the little town, the sailor in the harbour,

the peasant in the fields, the workman in his booth, and the

housewife as she plied her household duties, all would reverently

bow their heads and mutter their Paternosters and their Ave

Marias.

And thus the Hospital and Church of St. Anthony did a

great work in the social and religious life of the people of Leith, by

whom its canons were held in the highest regard and esteem. Naturally it

had numerous benefactors among them, who enriched it with many gifts, and

endowed it with the rents of considerable tracts of land. Among the many

benefactors of the Hospital, besides the founder, Sir Robert Logan, and

Dame Katharine, his wife, were Sir James Logan, his grandson and the first

of the Logans of the Sheriff Brae; William Logan, the founder of the

Coatfield family, and Patrick, his son; John Lamb, whose family lived in

Leith for nearly five hundred years; Maister David Monypenny (the "Maister"

shows him to have been a Priest) of the Pilrig family. Besides these there

were John Lawson, sea captain and pirate, who gave his name to Lawson’s

Wynd, an old Leith landmark only recently removed; his near neighbour,

Agnes Barton, the wife of his old friend John Barton, the first of the

famous Leith sea captains of that name; and Sir William Crichton, who gave

the Douglases their "Black Dinner" in Edinburgh Castle, and

afterwards gifted lands at Abbeyhill to the good canons to pray "for

his soul’s weal."

The

good canons of St. Anthony kept all these benefactors in grateful

remembrance. Their names were written on a long roll which always lay

near, or on, the high altar, and it was one of their rules to read "oppynly

thair namys als weil the quick as the deid, and that they be prayit for

every Sunday till the day of doom "—that is, they prayed for their

good estate while living, and for the welfare of their souls after death.

People of our time, looking back upon these old pre-Reformation days and

their religious customs so different from ours, are prone to say that men

then gave richly to the Church with the selfish purpose of having their

names remembered and their souls prayed for after death. Now we may be

sure that our ancestors of old pre-Reformation Leith were no less sincere

in the practice of their religion than we are today. It was customary

then, in bequeathing gifts to the Church, for the donors to stipulate for

the prayers of its members, who would, indeed, have been looked on as

wanting in proper religious feeling had they failed to do so. In bestowing

their gifts the sincere desire of the donors was for God’s mercy on

themselves along with "all faithful souls," and such a desire

was not an unworthy one. The

good canons of St. Anthony kept all these benefactors in grateful

remembrance. Their names were written on a long roll which always lay

near, or on, the high altar, and it was one of their rules to read "oppynly

thair namys als weil the quick as the deid, and that they be prayit for

every Sunday till the day of doom "—that is, they prayed for their

good estate while living, and for the welfare of their souls after death.

People of our time, looking back upon these old pre-Reformation days and

their religious customs so different from ours, are prone to say that men

then gave richly to the Church with the selfish purpose of having their

names remembered and their souls prayed for after death. Now we may be

sure that our ancestors of old pre-Reformation Leith were no less sincere

in the practice of their religion than we are today. It was customary

then, in bequeathing gifts to the Church, for the donors to stipulate for

the prayers of its members, who would, indeed, have been looked on as

wanting in proper religious feeling had they failed to do so. In bestowing

their gifts the sincere desire of the donors was for God’s mercy on

themselves along with "all faithful souls," and such a desire

was not an unworthy one.

The Hospital had been in

existence for some fifty years when evil times came, both to it and the

little town, and the green mounds in its churchyard suddenly and rapidly

increased in number. For in 1475 Leith was so sorely stricken with plague,

probably brought by some trader from plague-infested Danzig, that all the

people during the period of its continuance fled from

the town, and a hospital for the infected was established on Inchkeith. We

get a melancholy picture of the desolation wrought in Leith during such a

visitation in a letter written by the preceptor or master of St. Anthony’s.

In this letter the good preceptor says:

"Pestilence that

immediately proves fatal has cut off the friars of our order, and two

alone, myself and another, survive, who have saved our lives by removing

to a distance. Our house of St. Anthony lies empty. Our estates in the

town are deprived of their tenants, and our lands in the country of

farmers, so that our fields are untilled, and we ourselves deprived of the

alms of the faithful."

In addition to their

ordinary revenue from lands, rents, and gifts, the Hospital of St. Anthony

was en-titled to a Scots quart of wine out of every tan or cask imported

into Leith. This tax or impost added considerably to their annual income.

Wine being an article of foreign commerce, the Leith wine trade, wholesale

and retail, was the monopoly of the merchant burgesses of Edinburgh.

Leithers could, and did, keep taverns for the sale of ale and beer, but

they were not allowed to sell wines. The wine-sellers had formed

themselves into a fraternity or guild. No one could be a wine merchant in

our district who was not at the same time a free burgess of Edinburgh and

a member of this guild.

It was through this

fraternity or guild that the canons of St. Anthony received their impost

or money value of a quart from every tun of wine brought into the town,

and it was in all probability from this fact that: the wine merchants were

led to adopt St. Anthony as their patron saint, and called their guild the

"Fraternity of St. Anthony." Like all guilds, they had, and

maintained, a chaplain and altar in honour of their patron saint in the parish

church. This Chapel of St. Anthony was in the south transept of St.

Giles, and now forms the east portion of the Moray Aisle, for in it the

Good Regent Moray was buried.

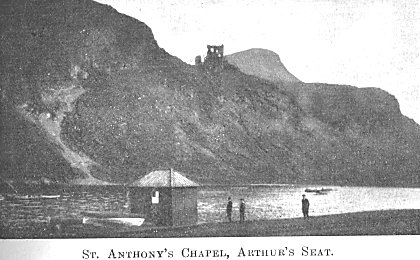

The ruined Chapel and

Hermitage of St. Anthony on the rocky spur of Arthur’s Seat, overlooking

St. Margaret’s Loch and the Firth of Forth, are popularly believed to

have been closely connected with the Hospital at Leith, and even to have

been built by its canons. Now there is no other foundation for these

statements than the similarity of name of the two foundations; for if we

have few charters belonging to St. Anthony’s Hospital, we have none at

all to tell us who founded the chapel on Arthur’s Seat. The tower of St.

Anthony’s Hospital was destroyed in 1560 by the English, and the

Hospital itself, like all the institutions of the Catholic Church, was

suppressed at the Reformation, which followed a little later in the same

year. All its rents and other properties (including the lands, gardens,

and windmill) in Leith and Newhaven were eventually bestowed by James VI.,

by his charter called the Golden Charter, on the Kirk Session of South

Leith.

The Hospital buildings were

greatly damaged by Hertford’s invasions of 1544 and 1547, and by the

cannon of the English at the siege of Leith in 1560. After the Reformation

they were allowed to fall into ruin, when they became a convenient quarry

for the erection of other buildings One of these was in all likelihood the

New Hospital, which was so called to distinguish it from the old Hospital

of St. Anthony, opposite the site of whose church in the Kirkgate it was

built on ground g ifted for that purpose by

William Balfour, merchant and

bailie of Leith. The rents of the lands and other Properties of the canons

of St. Anthony had been bestowed by King James on the South Leith Kirk

Session for the behoof of the poor of the town. They were erected into a

barony, and managed by a member of the Session, who was known as the Baron

Bailie of St.Anthony. The customary way of aiding the poor then, and for a

long time after, was to build a hospital or almshouse in which they might

reside. From funds derived from the rents of the old Hospital of St.

Anthony this New Hospital was built, and, in memory of the royal gift

granted by his Golden Charter, this new and later hospital was usually

designated King James’s Hospital, as you may read on a memorial stone

marking its site built into the wall of South Leith churchyard in the

Kirkgate.

The front of this later

hospital was adorned with a stone panel carved with the royal arms. That

stone is now built into the north face of South Leith Church tower; but

the recess, now empty, in which it formerly stood, still remains beside

the inscribed stone marking the site where King James’s Hospital

formerly stood. For over two hundred years after the canons of St. Anthony

had passed away their name and their memory continued, for the Kirk

Session called themselves the preceptors of St. Anthony, and in the church

records the old name recurs, showing that the New or King James’s

Hospital was the successor of the old pre-reformation charity founded by

the Logans, and was built and maintained from its funds. King James’s

Hospital was managed by the Kirk Session and the masters of the four trade

incorporations or guilds of the town, which included among their members

most of the inhabitants of the Port.

Only members of these

incorporations, their widows and children who were born and had lived in

Leith were eligible for admission to its benefits. But evil fortune seemed

to dog the New Hospital as it had done that of the good canons of St.

Anthony. The wine merchants paid the wine impost to the kirk session, as

they had done to the canons of St. Anthony, but more and more grudgingly,

until they refused to do so at all. and the property of the Hospital was

gradually alienated by the session to members of their own body.

The Hospital buildings were

removed in 1822, but the Hospital as an institution for aiding the poor

still goes on, and small pensions from its funds continue to be paid in

Leith. It still owns large tracts of land in the town, covered with

valuable buildings, but the feu duties derived from these are so small

that they are hardly worth the expense of collecting. Careful and

enlightened administration of its funds in bygone centuries would have

made King James’s Hospital a wealthy institution like the Heriot Trust,

and a source of untold benefit to the people of Leith.

Historical Notices of St. Anthony's Monastery

By Rev. Charles Rogers LL.D (1877) (pdf)

|