|

The lord advocate's speech on introducing the bill 'for the Amendment

and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Relief of the Poor

in Scotland' — Summary of the Act — The board of supervision constituted

--- Its first, second, and third Reports.

Tim' commissioners'

Report, of which a summary is given in the last chapter, together with

the appended dissent of one of their number, must be presumed to have

received from the government all the consideration which the importance

of the subject demanded; and in the following session (1845) a bill for

I the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the

Relief of the Poor in Scotland' was introduced by the lord advocate, who

in an able speech very clearly explained the existing state of the law,

the mode of its administration, and the defects which the bill was

intended to remedy. In doing this, he relied almost exclusively on the

commissioners' Report, which he highly commended as comprising all the

information that could be desired on the subject, and on which the bill

was accordingly founded. The dissent appended to the Report was not once

noticed, and little weight appears to have been attached to its

representations in framing the measure.

The several portions of

the subject were discussed by the lord advocate in the same order in

which they stand in the Report. They were likewise handled in the same

spirit. He made the same admissions as to the defects, and the same

assertions as to the merits of the existing system; and he also proposed

the same remedies for the one, and the same means for extending and

perpetuating the other. His speech was in short little more than a lucid

summary of the Report itself; and it is therefore not necessary, as it

else might have been, to go through it in detail, or to do more than

extract the sketch which he gave towards the conclusion of his address,

of what was intended to be the operation of the measure. He believed, he

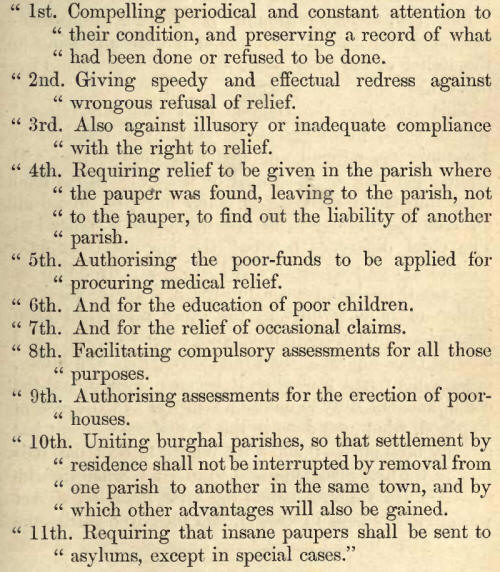

said, that the leading benefits it was calculated to confer on the poor,

were-

The bill for effecting

these several objects, was introduced on the 2nd of April, and after

considerable discussion was read a second time and committed on the 12th

of June. It was considered in committee and various amendments were made

on the 3rd, 11th, 17th, and 21st of July, on the last of which days it

was read a third time and passed. On the 28th of July the amended bill

was, on the motion of the duke of Buccleugh, considered and read a

second time in the Lords, and on the following day it was read a third

time and passed without further amendment. On the 4th of August the bill

received the royal assent, and became law, under the title of ' An Act

for the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the

Relief of the Poor in Scotland' (8th and 9th Vict. cap. 83.)

This Act, like the English Poor Law

Amendment Act of 1834, was founded on the recommendations of a

commission, specially appointed to inquire into and report upon the

subject in all its details; and it would seem impossible to devise a

better mode of procedure for effecting the object, or one less open to

objection. The chief difference between the circumstances into which the

two commissions had to inquire was, that in one case there had been a

profuse and lavish administration of relief, whilst in the other relief

had been insufficiently administered, or altogether withheld; and

against these opposite defects of stringency and laxity, of parsimony

and profusion, it became in each case the commissioners' duty to devise

a remedy. In the case of England, what was done in the way of amendment

has already been shown ;b and with regard to Scotland, it is now in the

first place proposed to give a summary of the new Act (in framing which

the Irish Poor Relief Act was obviously kept in view), and then to

describe the steps taken for carrying its provisions into effect,

together with a detail of the results from year to year down to the end

of 1852-3. Summary

of the 8th and 9th Victoria, cap. 83, (4th August 1845,)

For the Amendment and better Administration

of the Laws relating to the Relief of the Poor in Scotland.

Section 1.---Contains the preamble,

declaring it to be "expedient that the laws relating to the relief of

the poor in Scotland should be amended, and that provision should be

made for the better administration thereof;" and also the interpretation

of certain words and expressions used in the Act.

Section 2.—Appoints a "Board of Supervision

for Relief of the Poor in Scotland," consisting of the lord provost of

Edinburgh, the lord provost of Glasgow, the solicitor-general of

Scotland, the sheriffs depute of the counties of Perth Renfrew Ross and

Cromarty, together with three other persons to be appointed by the

crown. Sections 3,

4.—Provide that one member of the board of supervision, to be named by

the crown, shall be paid a salary, and likewise the secretary ; but that

all the other members are to act gratuitously.

Sections 5, 6.—The board of supervision are

to hold two general meetings in each year, on the first Wednesday in

February and August respectively, and may adjourn and hold meetings from

time to time as they shall see fit, three constituting a quorum. The

board may also appoint two or more of their number as a committee for

the purposes of the Act. The paid member is not only to attend the

general and special meetings, but is also "to give regular attendance

for the purpose of conducting the business of the board."

Sections 7, 8.—The board may, subject to the

approval of one of her Majesty's principal secretaries of state, make

general rules and regulations for conducting the business, and for

exercising the powers and authorities thereof: A record of all their

proceedings is to be kept, and once in every year they are to submit a

general report, to be laid before parliament, containing "a full

statement as to the condition and management of the poor throughout

Scotland, and the funds raised for their relief."

Sections 9, 10, 11.—The board are empowered

"to inquire into the management of the poor in every parish or burgh in

Scotland," and to require answers and returns on all matters connected

with or relating to the same ; and also to summon and examine upon oath

such persons as they think fit, "and to enforce the production of all

books, contracts, agreements, accounts, and writings in any wise

relating to any such question or matter." The board may appoint one of

its members to conduct any special inquiry, with power to summon and

examine witnesses on oath, and may likewise with consent or by direction

of a secretary of state or the lord advocate for the time being, appoint

one or more persons (not being members of the board), "to act as

commissioners for conducting any special inquiry, for a period not

exceeding forty days;" and may delegate to the persons so appointed,

such powers as the board shall deem necessary.

Sections 12,. 13, 14.—The board may allow

such expenses of witnesses,, and with regard to the production of books

&c., as they think reasonable. Persons giving false evidence are to be

deemed guilty of perjury; and any person who shall refuse to produce

books &c., or shall disobey any summons or order, "or be guilty of any

contempt of the said board or committee or member or commissioner," is

for the first offence liable to forfeit 51., and for the second and

every subsequent offence will be liable to forfeit not exceeding 201,

nor less than 51.—The board are moreover empowered to appoint "such

clerks messengers and officers as they shall deem necessary," the

salaries being regulated by the treasury.

Section 15.—The members of the board and the

secretary are authorised to attend the meetings of parochial boards for

the management of the poor, and to take part in the discussions, but not

to vote; and the same privilege is extended to any clerk or officer of

the board duly authorised by them for the purpose.

Section 16.—Where the parochial boards of

two or more parishes deem it expedient to combine for the administration

of the laws for the relief of the poor, and where the board of

supervision is satisfied of the expediency, the board are empowered "to

resolve and declare that such parishes shall thenceforward be combined,

and shall be considered as one parish, so far as regards the support and

management of the poor, and all matters connected therewith." But it is

provided that any adjacent parish may, upon application, be added

thereto, if the board of supervision see fit, "due regard being had to

the circumstances of the case."

Sections 17, 18.—In every burghal parish or

combination of parishes, there is to be a parochial board of managers of

the poor, in whom the whole administration of the laws for the relief of

the poor is to be vested, and on whom is devolved all the powers and

authorities in this respect hitherto exercised by magistrates or other

functionaries. The managers are to be elected by the persons assessed to

the relief of the poor, and the parochial boards are to consist of such

number of managers not exceeding thirty, and possessing such

qualifications, "as the board of supervision, having due regard to the

population and other circumstances, may from time to time fix, such

qualification being in no case fixed at a higher annual value than 501."

The magistrates of the burgle, and the kirk session of each combined

parish, are likewise severally empowered to nominate four persons to be

members of the parochial board. The board of supervision are to fix a

day for the election of managers, and are also to fix the time for the

magistrates and the kirk sessions "to nominate the persons to be by them

respectively nominated to be members of the parochial board," all of

whom "shall be entitled to act for the period of one year, and may be

re-elected or re-appointed."

Section 19.—At the election of managers of

the poor, the votes are to be taken in such manner as the board of

supervision may direct, every person assessed for the support of the

poor being "entitled to vote, whether such assessment be made in respect

of ownership or occupancy of lands and heritages, or in respect of

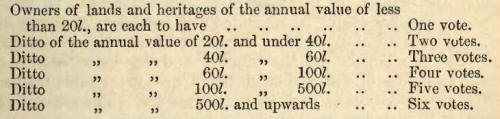

means, and substance." The number of votes is regulated according to the

following scale-

Persons assessed as the occupants of lands

and heritages, or assessed on means and substance, are each to have the

same number of votes as an owner of lands and heritages assessed to the

same amount would have. Where an occupant is also the owner, and

assessed in both capacities, he will be entitled to vote as well in

respect of his ownership as of his occupancy; and so likewise where a

person is assessed on his means and substance, if he be also assessed as

an owner of lands and heritages, lie will be entitled to vote in respect

of both—provided that no person shall have more than six votes, and that

no one shall be entitled to vote who has been exempted from the payment

of his rates, or who shall not have paid the rates clue from him at the

time of voting.

Sections 20, 21.—The board of supervision are empowered to divide a

burghal parish or combination into wards, for the election of managers

and to apportion the number of managers to be elected by each ward,

"having due regard to the population and the value of property therein."

But residents only are entitled to vote for managers in the ward, or

have a right to vote in respect of ownership or occupancy of lands and

hereditaments within it—neither shall "any person give in the whole of

the wards into which a, parish may be divided, a greater number of votes

than he would be entitled to give if the parish had not been so

divided." The books of the collector of the assessment for the poor are

to be taken as evidence for ascertaining the number of votes to which

each person is entitled.

Sections 22, 23, 24.—Parochial boards for

the management of the poor, are also to be constituted in the parishes

which are not burghal or in combination. Where no assessment has been

made, the parochial board is "to consist of the persons who, if this Act

had not been passed, would have been entitled to administer the laws for

relief of the poor in such parish." Where an assessment has been made,

the parochial board is to consist of the owners of lands and heritages

of the yearly value of 20l. and upwards, and the provost and

bailies of the royal burgh, if any, and if assessed in such parish, and

the kirk session of the parish (not exceeding six)) together with a

certain number of elected members. All persons who are assessed in the

parish, and who are not members of the parochial board, are to elect so

many of their own number to be members thereof as shall " be. regulated

and fixed from time to time by the board of supervision, due regard

being had to the amount of the population, the number and residence of

the other members of the parochial board, and the special wants and

circumstances of each particular parish." The scale of voting is the

same as prescribed in Section 19.

Sections 25, 26.—Corporations and joint

stock companies may vote by their officer, or one of their body

nominated for the purpose. Any member of the parochial board, being a

heritor, may appoint another to act and vote for him in his absence, and

husbands are entitled to act and vote in right of their wives.

Sections 27, 28, 29.—All disputes touching

the election of a member of the parochial board are to be determined by

the sheriff of the county, and pending such decision the person returned

is entitled to act. A returning officer wilfully making a false return,

is liable to a penalty of 50l.

Sections 30, 31, 32.—Parochial boards are to

fix certain (lays and places for holding general. meetings, and may

adjourn such meetings as they think fit; but two general meetings at

least must be held yearly, one on the first Tuesday of February, and the

other on the first Tuesday of August, or as soon thereafter as may be,

"or at, such other stated times as may be approved by the board of

supervision." Special meetings may also be held, and power is given to

appoint committees to act on behalf of the whole board. A chairman is to

he elected annually, and is to have both an original and a casting vote

in case of equality. "A roll of the poor persons claiming and by law

entitled to relief, and of the amount of relief given or to be given to

each," is to be made by every parochial board. These boards are also t.o

appoint inspectors of the poor, and fix the amount of their

remuneration, and report the same to the board of supervision.

Sections 33, 34, 35.—Parochial boards may,

after due notice, resolve that the funds required for relief of the poor

shall be raised by assessment, reporting the same to the board of

supervision ; and thereafter "it shall not be lawful to alter or depart

from such resolution without the consent and authority of the board of

supervision." The parochial board may resolve that the assessment shall

be imposed half upon the owners and half upon the tenants or occupiers

within the parish, or one half upon the owners and the other half upon

the whole inhabitants according to their means and substance —or may

resolve that the "assessment shall be imposed as an equal percentage

upon the annual value of all lands and heritages within the parish, and

upon the estimated annual income of the whole inhabitants from means and

substance;" and in either case the resolution is forthwith to be

reported to the board of supervision for approval. If the same be

disapproved, the parochial board are "to meet and resolve upon another

mode of assessment consistent with the law," and report as before; and

if the board of supervision shall then approve, the resolution is to be

acted upon, and not thereafter altered or departed from without the

board's consent. If the assessments have hitherto been imposed under any

local Act, "or according to any established usage," the parochial board

may resolve that the same shall continue, subject in like manner to the

approval of the board of supervision.

Sections 36, 37.—The parochial board, with

consent of the board of supervision, may classify lands according to the

purposes for which they are used, and may fix such rate of assessment

upon each class respectively as seems just and equitable.

In estimating the annual value of lands and

heritages, the same shall be taken to be the rent at which, one year

with another, such lands and heritages might in their actual state be

reasonably expected to 'let from year to year, under deduction of the

probable annual average cost of the repairs, insurance, and other

expenses, if any, necessary to maintain such lands and heritages in

their actual state, and all rates taxes and public charges payable in

respect of the same."

Sections 38, 39,

40.—Where assessment is adopted, the parochial board is to cause a book

to be made up "containing a roll of the persons liable to payment of

such assessment, and of the sums to be levied from each of such persons,

distinguishing the sums assessed in respect of ownership or occupancy,

or means and substance; and the book or roll so made up shall be the

rule for levying the assessment for the year or half-year then ensuing."

The parochial board is also to appoint a collector or collectors, and

fix the amount of remuneration; and the same person who is an inspector

of the poor may likewise be appointed collector of the assessments.

After the assessment roll is made up, the collector is to intimate to

each person the amount to be levied from him, and the time when the same

is payable. Parochial boards may correct any error or omission in the

assessment, and persons aggrieved may obtain remedy by law, as before

the passing of the present Act.

Sections 41, 42, 43, 44.—If the assessment

in any year or half-year proves insufficient, the parochial board may

impose such further assessment as is necessary; and they may exempt from

payment of the assessment, or any part thereof, "to such extent as may

seem proper and reasonable, any person or class of persons on the ground

of inability." Where half the assessment is imposed on the owners and

half on the tenants, the collector may levy the whole from the latter,

"who shall be entitled to recover one half thereof from the owners, or

to retain the same out of their rents." And where houses have been built

under a building lease, the tenant is to be deemed the owner.

Sections 45, 46, 47, 48, 49.—Where a canal

or railway is situate in more than one parish, the value on which

assessment is to be made "shall be according to the number of miles or

distance which such canal or railway passes through or is situated in

each parish, in proportion to the whole length." The same property is

not liable to assessment in more than one parish. Where an assessment is

imposed on means and substance, individuals or companies carrying on

business in a parish, are liable to be assessed on their means and

substance derived from such business, although none of them may be

actually resident in the parish; but they are not liable to be assessed

upon the same means and substance in any other parish; and if any person

shall be liable to be assessed as an inhabitant of more than one parish,

he may determine in which he will be assessed on his means and substance

derivable elsewhere. No person is liable to be assessed on means and

substance, unless the estimated annual value thereof exceeds 30l

; and clergymen are not liable to be assessed in respect of their

stipends. Sections

50, 51.—The privilege of exemption from assessment heretofore enjoyed by

the members of the college of justice, and the officers of the queen's

household in Edinburgh, is not to apply to assessments under the present

Act; and no assessment is to be rendered void by "any mistake or

variance in the naive or designation of the person chargeable

therewith."

Sections 52, 53, 54.—Parish property of every description, whether

heritable or moveable, "or under any law or usage, or in virtue of gift,

grant, bequest or otherwise, for the use or benefit of the poor," is to

become vested in the new parochial boards, and be by them administered

for behoof of the poor of the respective parishes. All sums of money or

other funds given, mortified, or bequeathed for the use of the poor, if

not specially directed otherwise, are to be lodged in a chartered bank,

or placed at interest on government or heritable security; and the board

of supervision may require returns from time to time as to all such

money or funds. But all moneys arising from ordinary church collections

in a parish, whenever an assessment has been imposed, are to be at the

disposal of the kirk session, who are however "bound.to report annually

or oftener if required to the board of supervision, as to the

application of the moneys arising from church collections."

Sections 55, 56, 57, 58.—The inspector of

the poor is to have the custody of all books writings accounts and other

documents relating to the management or relief of the poor, and is to

make himself acquainted with the circumstances of each of the poor

persons receiving relief, and keep a register of such persons and of the

sums paid to them, and of all persons who have applied for and been

refused relief, with the grounds of refusal; and he is to visit and

inspect personally, "at least twice in the year (or oftener if

required), at their places of residence, all the poor persons belonging

to the parish in receipt of parochial relief—provided that such poor

persons be resident within five miles of any part of such parish." But

in populous and extensive parishes, the duties of inspecting and

visiting the poor may be performed by assistant inspectors, for whose

conduct and accuracy the inspector of the poor is nevertheless

responsible to the board of supervision, who may suspend or dismiss any

inspector deemed by them to be incompetent. An action may be brought,

and may also be defended, on behalf of a parish by the inspector of the

poor, and actions brought by or against any inspector of the poor in his

official character, are to be continued by or against his successors in

office. Section

59.—The inspectors of the poor are required to report to the board of

supervision all cases of insane or fatuous persons chargeable as

paupers, who are to be conveyed to and dodged in some establishment

legally authorised to receive lunatic patients ; and if this be not done

within fourteen days, the board of supervision are empowered to take

measures for effecting the same, and to recover the whole expense from

the parochial board.

Section G0, 61, 62, 63.—"For the more

effectually administering to the wants of the aged and other friendless

impotent poor, and also providing for those poor persons who from

weakness or facility of mind, or by reason of dissipated and improvident

habits, are unable or unfit to take charge of their own affairs" —it is

enacted, that whenever the inhabitants exceed 5000, the parochial board

may, subject to the approval of the board of supervision, erect a new or

enlarge an existing poorhouse. And with the concurrence of the board of

supervision, two or more contiguous parishes may unite in building a

common poorhouse, the expense to be borne proportionally, as shall be

agreed upon. The parochial boards are likewise empowered to borrow money

for building and enlarging such poorhouses, and to charge the future

assessments with the amount; but the principal sum so borrowed is in no

case to exceed three times the amount of the assessment raised for the

relief of the poor during the year preceding, and the loan borrowed is

to be " repaid by annual instalments of not less in any one year than

one-tenth of the sum borrowed, exclusive of the payment of the interest

on the same." But no poorhouse is to be built, altered, or enlarged, nor

money borrowed for such purpose, unless the plans be approved by the

board of supervision.

Sections 64,. 65.—The parochial boards are

required to frame rules and regulations for the management of the

poorhouses, for the discipline and treatment of the inmates, and for

affording them religious assistance, such rules and regulations being

subject to the approval of the board of supervision. Poor persons of one

parish may be accommodated in the poorhouse of another, on payment of

such a rate of maintenance as the beard of supervision approve.

Sections 66, 67.—The parochial board are to

appoint a properly qualified medical man to attend the inmates of the

poorhouse, and assign him a reasonable salary; and are to make

arrangements for dispensing and supplying medicines to the sick poor,

under regulations to be approved by the board of supervision, who are

moreover empowered to suspend or remove any medical man that appears to

be "unfit or incompetent, or neglects his duty." Parochial boards may

likewise subscribe such sums as to them may seem reasonable or

expedient, "to any public infirmary dispensary or lying-in hospital, or

to any lunatic asylum or asylum for the blind or deaf or dumb."

Sections 68, 69.—All assessments levied for

relief of the poor, are applicable to the relief of occasional as well

as permanent poor—"provided that nothing herein contained shall be held

to confer a right to demand relief on able-bodied persons out of

employment." The parochial boards are required "to provide for

medicines, medical attendance, nutritious diet, cordials and clothing

for such poor, in such manner and to such extent as may seem equitable

and expedient." They are also empowered "to make provision for the

education of poor children, who are themselves or whose parents are

objects of parochial relief."

Sections 70, 71, 72, 73.—Inspectors of the

poor are bound to furnish applicints for relief who are legally entitled

thereto, but who have not a settlement in the parish, with sufficient

means of subsistence until the next meeting of the parochial board, and

such interim maintenance as may be adjudged necessary is to be

continued, until the parish to which the poor person belongs is

ascertained, or until he is removed. The amount disbursed on behalf of

such poor persons is recoverable from the parish of their settlement,

provided it do not exceed the rate expended for relief of the poor in

the relieving parish. If relief be refused, application may be made to

the sheriff, who if he consider the poor person "legally entitled to

relief," may make an order upon the inspector of the poor, directing him

to afford relief until he have stated in writing why the relief was

refused, and until such statement be answered on behalf of the

applicant. But the sheriff has no power "to determine on the adequacy of

the relief afforded, or to interfere in respect of the amount of relief

in any individual case."

Sections 74, 75.--If any poor person

considers the relief granted him inadequate, he may lodge a complaint

with the board of supervision, who are required to investigate the case,

and if the complaint appears to be ;well founded, the board "shall by

minute declare that in the opinion of the board such poor. person has a

just cause of action against the parish from which he claims relief;"

and a copy of such minute being furnished to such poor person, will

entitle him "to the benefit of the poor's roll in the court of session."

But no court of law can entertain or decide any action relative to the

amounts of relief granted by parochial boards, "unless the board of

supervision shall previously have declared that there is just cause of

action, as hereinbefore provided."

Sections 76, 77, 78, 79.—No person is to be

held to have acquired a settlement by residence in any parish, unless he

has resided for five years continuously therein, and "have maintained

himself without having recourse to common begging, either by himself or

his family, and without having received or applied for parochial

relief." And a person who has acquired a settlement by residence in a

parish, "shall not be held to have retained such settlement, if during

any subsequent period of five years lie shall not have resided in such

parish for at least one year." Settlements acquired previous to the

passing of the Act, are specially exempted from its operation. Natives

of England, Ireland, or the Isle of Man, not having acquired a

settlement, and who are "in course of receiving relief in any parish in

Scotland," may upon complaint by the inspector of the poor, and after

examination before the sheriff or any two justices of peace, and by

order under their hands, be removed at the expense of the complaining

parish, to England Ireland or the Isle of Man respectively—a certificate

by a regular medical practitioner that the health of the parties will

admit of such removal being first obtained, and the removing officer is

to have the power of a constable whilst effecting the removal. If any

person who has been so removed return to Scotland, and apply for relief,

or again become chargeable, "such person shall be deemed to be a

vagabond under the provisions of the Act of 1579, cap. 74," and may be

apprehended and prosecuted criminally at the instance of the inspector

of the poor of the parish to which he shall have so applied or become

chargeable. Section

80.—Every husband or father who deserts, or neglects to maintain his

wife or children, being able so to do, and every mother and every

putative father of an illegitimate child, after the paternity has been

admitted or otherwise established, who refuses or neglects to maintain

such child, being able to do so, whereby such wife or child becomes

chargeable to any parish, "shall be deemed to be a vagabond under the

Scottish Act of 1579, cap. 74," and may be prosecuted criminally at the

instance of the inspector of the poor of such parish, and if convicted

is punishable by fine or imprisonment with or without hard labour, at

the discretion of the sheriff.

Sections 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86.—The

penalties imposed by this Act may be recovered by summary proceeding in

the name of the secretary to the board of supervision, or of any agent

appointed by the board. And the sheriff by whom any such penalty is

imposed, is to award the same to the poor of the parish where the

offence was committed, and order the amount to be paid over to the

inspector of the poor. Ratepayers are to be deemed competent witnesses

in any proceeding for the recovery of a penalty, and any person summoned

to give evidence in any matter under the provisions of this Act, who

neglects or refuses to attend, or to be examined on oath for that

purpose, is to forfeit a sum not exceeding 51. for every such offence.

No proceeding for recovery of penalties under this Act is to be set

aside for want of form, nor be removed by appeal or otherwise into any

superior court. Actions are to be brought within three months after the

fact committed, and at least one month's notice of action and the cause

thereof is to be given to the defender; and no pursuer is to recover in

any action for irregular or wrongful proceedings, if tender of

sufficient amends be made.

Section 87.—In case any parochial board

shall refuse or neglect to do what is by law required of then, or in

case any obstruction arises in the execution of this Act, the board of

supervision are empowered to apply by summary petition to the court of

session, or in its vacation to the lord ordinary, "which court and lord

ordinary are authorised and directed in such case to do therein, as to

such court or lord ordinary shall seem just and necessary."

Section 88.—All the powers and rights of

issuing summary warrants and proceedings, and all remedies and

provisions for collecting and recovering the land, assessed, and other

public taxes, are made applicable to assessments for the relief of the

poor; "and the sheriffs, magistrates, justices of peace and other

judges, may grant the like warrants for the recovery of all such

assessments in the same form, and under the same penalties, as is

provided in regard to such land, assessed, and other public taxes." In

cases of bankruptcy or insolvency, assessments for relief of the poor

are to be paid out of the first proceeds of the estate, in preference to

other debts of a private nature.

Section 89.—If any parochial board finds it

necessary to make disbursements for the relief of the poor, beyond the

amount received of the assessment for the year, or the half-year, the

board may borrow on security of such part as is still due, not exceeding

one half the amount of such part; and until this be repaid, no money is

to be borrowed on any future assessment.

Section 90.—In all cases where notice or

intimation is required to be given by this Act, without prescribing the

particular form, the board of supervision are empowered "from time to

time to fix the form of such notice or intimation, and the manner in

which the same is to be given."

Sections 91, 9.2.—All laws statutes and

usages, so far as they are at variance or inconsistent with the

provisions of this Act are repealed, but they are to continue in force

in all other respects. "The debt owing by the charity workhouse of the

city of Edinburgh" is exempted from the operation of the Act. And

section 92 provides that the Act may be renewed or repealed during the

present session.

The Act, of which the foregoing is a comprehensive summary, contains

many important provisions, and no doubt goes far to remove some of the

uncertainties, and to supply several of the deficiencies, which existed

under the old Scottish law with regard to the relief of the poor. By

establishing regularly constituted parochial boards of management, and a

board of general supervision, a machinery is moreover created competent

to the discharge of all the duties imposed by the Act, and of still more

extensive duties should such hereafter be required; whilst the power of

levying assessments, and of combining parishes for the erection of

poorhouses and providing medical relief, together with the appointment

of inspectors, and the more certain provision for relief of the lunatic

casual and unsettled poor, and for the purpose of education, are all

exceedingly valuable additions to the former system, and cannot fail of

being productive of much benefit.

The Act makes no change in the description

of persons legally entitled to relief under the old law. In England all

destitute persons are so entitled, but in Scotland the right is still,

in conformity with the recommendation of the commissioners of inquiry,

limited to the aged and infirm poor. The functions of the board of

supervision are chiefly suggestive or corrective —the commissioners may

inquire and call for returns, or may recommend a course of procedure,

but are not empowered to take the initiative. If invoked, they may

combine parishes- for providing a poorhouse; but unless applied to by

the local boards they have 'no power to direct this to be done, and can

only require them to meet and consider the question; and so in other

matters. Their usefulness in securing an effective administration of

relief, must therefore be necessarily less than it would be if they were

not so restricted, and the new law will perhaps work less efficiently in

consequence. With respect to the vexed question of settlement, the term

of residence for conferring a right, is fixed intermediately between the

three ,years of the former practice, and the seven recommended by the

inquiry commissioners; and the continuance of the right, is made to

depend upon the party not applying for relief or resorting to common

begging, and also on his residing in the parish continuously for one

year at least, during any subsequent five years.

No further observations appear to be at

present called for in regard to the provisions of this important Act,

and we will now therefore proceed to describe the steps which were taken

for carrying it into effect, and the general results attending its

application. The

'Act for the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to

the Relief of the Poor in Scotland,' was passed on the 4th of August

1845; and on the 4th of September following the board of supervision

constituted under it met in Edinburgh for the transaction of business,

Sir Johan McNeill, G. C.B. being appointed the paid commissioner and

chairman of the board, and William Smythe Esq. secretary. At the end of

a year, that is in August 184G, the board, as required by the 8th

section of the Act, made their Report, in which they give a full

statement of the proceedings for bringing the law into operation. Of

this first Report, and of the others subsequently made in like manner,

it is proposed in the following pages to give a summary, omitting only

the merely technical and less important matters; but still affording

such explanations as will enable the reader to judge of the progress and

the effects of the new law.

One of the first duties required from the

board of supervision, was to afford assistance and information to the

several parishes in constituting the new parochial boards, and in

appointing inspectors of the poor, there being, it is said, "in many

parishes a misapprehension as to the objects of the legislature in

respect to these matters, and a diversity of opinion as to the mode of

proceeding to effect them."

The constitution of the parochial boards, on

whom the administration of relief to the poor exclusively devolved, was

no doubt an object of primary importance; and although provided for with

great minuteness in the 17th and following sections of the Act, there

were yet certain things left undetermined, and subject to the directions

of the board of supervision, who lost no time in preparing the necessary

instructions and regulations on every point requiring the exercise of

their authority. The board opened its communication with the several

parishes by addressing a letter to each, pointing out what was required

under the 32nd section of the Act, and advising the parish authorities

as to their holding meetings, making up a roll of the poor, appointing

inspectors, and settling the mode of raising the necessary funds. Most

of the persons named as inspectors, were necessarily unacquainted with

the duties of the office, and the system of management they were called

upon to carry out was new to then all." The commissioners therefore

framed rules for their guidance, and to which after being approved by a

secretary of state, the inspectors were bound to conform. At the end of

the first year, every parish-in Scotland had, we are told., named an

inspector ; and the commissioners observe, that due allowance being made

for inexperience, the duties have generally been well performed.

After making up the poor's roll, and

appointing an inspector, the parochial boards had next to determine

whether the funds required for the relief of the poor should be "raised

by voluntary contributions or by legal assessment." Both modes were

practised under the old law,.but the former was the one most generally

adopted. Out of the 878 parishes into which Scotland was then divided,

only about 230 were legally assessed in 1842-3. The number which

however, at the date of the commissioners' Report, had resolved to raise

the funds for relief of the poor by assessment, was increased to 448,

being something more than one half of the entire number.

Under the old law, all the inhabitants of

purely burghal parishes were assessed "according to the estimation of

their means and substance," in terms of the statute of 1579; but in

landward parishes "half the burden was laid on the owners of lands and

heritages within the parish, and the other half on the whole inhabitants

according to their means and substance." By the new Act three modes of

assessment are provided, and it is left to each parochial board to adopt

whichever of the three may be considered best suited to the

circumstances of the parish. Half the assessment may be imposed upon the

owners, and half upon the occupiers; or one half upon the owners, and

the other half upon the whole inhabitants, according to their means and

substance; or the whole may be imposed as an equal percentage on the

annual income derived from both sources indifferently. Whenever the

first mode is adopted, the 36th section empowers the parochial board "to

distinguish lands and heritages into two or more classes according to

the purposes for which they are used or occupied, and to fix such

different rates of assessment on the tenants and occupants of each class

as may seem just and equitable." In all these modes, the commissioners

remark, "that which may be regarded as the national principle, that each

man shall be assessed in proportion to his means, has in effect been

preserved." And they further add, that "none of the modes established by

usage are opposed to the principle of the old law under which they were

adopted, neither are any of the local Acts at variance with the

principle on which the law was founded."

In determining the mode in which a parish

should be assessed, the parochial board had not therefore to consider

the principle as to whether each man should be assessed according to his

means, but whether the assessment should be imposed directly upon his

estimated means and substance, or indirectly by assuming that the house

or lands occupied by him represented his means and substance

proportionally with the other ratepayers. In a great majority of

parishes, the commissioners say, the indirect mode of estimating means

and substance, by taking annual value or rent as the criterion, has been

preferred, the numbers being 379 for that mode of assessment, and 66 for

the other modes; and they "think it not very unlikely that the second

and third modes of assessment mentioned in the Act, may gradually be

abandoned, and the first mode, with or without classification, adopted

by all or nearly all the parishes in Scotland."

At the date of the Report., all the parishes

in Scotland bad either by assessment, church collections, contributions,

or other means, provided the funds required for the relief of the poor,

and it is satisfactory to find that in no case had the commissioners

found it necessary to avail themselves of the power given them by the

87th section, of applying by summary petition to the court of session in

case of refusal or neglect in doing what the law requires.

The 16th section of the Act empowers the

board of supervision, either on application or otherwise, to require the

parochial boards of two or more adjoining parishes to meet and consider

the expediency of their combining for the management of their poor, and

if it be resolved that it is expedient and proper for them so to

combine, the board of supervision may declare such parishes to be

thenceforward combined accordingly. It appears however that only two

applications had yet been made for this purpose, and that the

commissioners were enabled to exercise the power confided to them in one

only of these, by combining the three parishes of the island of Islay

which belonged almost exclusively to one proprietor. The requisite

consent of all the parishes was not given in the other case.

The practice of giving passes to poor

persons, authorising them to ask relief in the places through which they

passed in their way to their own parish, had long prevailed under

sanction of the Act of 1579. But there was no certainty that the person

receiving the pass had a settlement in the parish to which he

represented himself to belong, and the pass often became a cover to

fraud, and a warrant for mendicancy. A poor person legally entitled to

relief has, under the new law, a right to claim such relief in any

parish where he may apply for it;'` and the relief is to be continued

until the parish of his settlement be ascertained, by which parish the

cost of such interim relief, and the expense of the pauper's removal, is

to be borne. The ground for granting such passes therefore no longer

existed, and steps were taken for putting an end to the practice. The

commissioners say that the rule they endeavoured to enforce was, "that a

poor person, who has applied for relief in any parish, is not to be

removed, or provided with the means of -removal, to any other parish in

Scotland than that which has been ascertained to be the parish of his

settlement." English and Irish paupers will, they add, under this rule,

"be removed from the parish in which they may apply for relief, to their

native country, instead of being passed on as heretofore from parish to

parish." But to protect English and Irish paupers from unnecessary

hardship in their removal, a letter was addressed to the inspectors of

the poor of the parochial boards, recommending attention to the health,,

and comfort of all such paupers, and also recommending that those who

are to be removed by sea, should be conveyed to a port with which there

is such regular communication as may afford the greatest likelihood of

their speedily reaching the place of their destination.

The facility of obtaining relief under the

new law by persons legally entitled to it, elsewhere than in the parish

of their settlement, is said thus early to have considerably increased

the charge of the casual poor. The cost of the relief afforded to

non-settled Scottish paupers, is recoverable from the parishes to which

they belong. The number of English paupers is noticed as being

comparatively small. "But the number of natives of Ireland, or of their

families, who receive casual relief, and who are removed to Ireland at

the cost of the different parishes in Scotland, especially Glasgow and

other towns on the `vest coast, is very considerable." A table in the

appendix to the Report shows the number of persons so removed from

Glasgow, between August 1845 and 25th July 1846, to have been 1949, at a

cost of 133l. 16s. 9d.

With respect to the important question of

poorhouses, the erection and management of which are provided for by the

60th and four following sections of the new Act, it is stated that

several parishes, either singly or conjointly with contiguous parishes,

have taken into consideration the expediency of erecting poorhouses; but

hitherto, the commissioners say, "no resolution to erect a poorhouse has

been transmitted to us by any parochial board." It appears however that

certain parishes in the counties of Caithness and Ross proposed to erect

poorhouses, if the commissioners were prepared to admit the right of the

parochial boards to refuse relief to any poor person who might refuse to

enter the poorhouse. But the commissioners were of opinion, that they

"had no power to sanction the abolition of out-door relief in any

parish, and that they must judge of the propriety of refusing to relieve

a pauper otherwise than by admitting him into the poorhouse, with

reference to the circumstances of each case." The question whether a

parochial board could legally refuse relief except in the poorhouse

might, the commissioners believed, come to be decided in a court of law,

and therefore it would be wrong in them to give an opinion with regard

to it. [A case involving this question did in fact subsequently arise at

Glasgow, —a person entitled to relief was offered admission to the

poorhouse, and was refused other relief. An action was brought against

the parish for illegally refusing relief, but the sheriff held that the

parish had not acted illegally in the matter, and dismissed the case. It

appears therefore, as the commissioners remarked at the time, that the

only question the sheriff has to decide is, whether the claimant is or

is not entitled to relief—he is not empowered to judge of its adequacy

or fitness.] Some communications which had taken place with certain

parochial boards on the subject of poorhouses are then noticed, after

which the commissioners conclude this head of their Report by declaring,

that although they have been strongly impressed with the advantages

which both the poor and the ratepayers in many parishes would derive

from the erection of poorhouses, they have nevertheless abstained from

pressing this opinion on any parochial board—"We do not," they say,

"doubt that experience will lead them to the same convictions that have

forced themselves upon our minds, and in any event we are satisfied that

it is more advisable to leave them to pursue the course that may to them

appear the most expedient, than to press upon them measures involving a

considerable present expenditure, to remedy evils which they have either

not yet experienced or not fully appreciated, and for which. it will not

be too late to provide a remedy when they have become urgent."

By the 69th section of the new Act,

parochial boards are required to provide medicines, medical attendance,

nutritious diet, cordials, and clothing for the sick poor, "in such

manner and to such extent as may seem equitable and expedient." Before

this there was no provision for medical relief, and the assistance the

sick poor received, was for the most part afforded gratuitously by the

resident practitioners in the several parishes. The commissioners very

early called the attention of parochial boards to this section of the

Act, and they likewise, in framing the rules for the inspectors of the

poor, made it their duty "in all cases of sickness or accident befalling

persons entitled to relief," and also "in every case of sickness or

accident of any person in receipt of parochial relief," not only to take

measures for procuring without delay such medical aid as can be

obtained, but as soon as may be, and from time to time afterwards, "to

visit the home of such sick person, and supply him with such articles as

may seem necessary, until the case shall have been reported at the next

meeting of the parochial board." This was probably, under the

circumstances, all that the commissioners could directly do towards

securing needful relief for the sick poor, although their influence

would no doubt be still further exerted in forwarding that object. It

appears that in a large majority of the parishes, no salary had yet been

assigned to a medical officer. In a considerable number this had however

been done, and in some instances parishes situated near towns in which

there were hospitals or dispensaries, had subscribed thereto on behalf

of their sick poor. The commissioners are, as was to be expected, far

from thinking "that the medical relief afforded to the poor in Scotland,

more especially in the rural and remote parishes, is on a satisfactory

footing." In some of the town parishes, and in a few of the rural

parishes, medical relief is, they say, adequately provided for; but in a

great majority of parishes much yet remains to be done. They hopefully

add however, that "the intention of government to contribute from the

public funds a considerable sum towards defraying the cost of medical

relief in Scotland, will afford an opportunity of revising the whole

system, and of placing it on a much more satisfactory footing than it

has hitherto been."

Parochial boards are required by the 59th

section of the Act, to remove all insane or fatuous paupers to an

asylum, unless the board of supervision, under special circumstances,

dispense with such removal, in which case the paupers are to be provided

for in such manner as the board of supervision shall approve. By returns

which the commissioners obtained, it appears that the number of lunatic

paupers not accommodated in any asylum, amounted to 1621, whilst

according to another return, there was only available accommodation for

82 in public asylums, and for 52 in private establishments, making

together 134 vacancies; so that not even a tenth part oft the entire

number of pauper lunatics could be dealt with as required by the Act.

The cominissioners therefore insisted on the removal of such only, as

they had reason to believe from the reports of the medical men were

likely to be benefited by being sent to an asylum, or who might become

dangerous or offensive to decency; and they expressed their regret "that

the accommodation in Scotland for lunatics generally is so limited, and

that the existing asylums are for the most part filled with incurable

patients, to the exclusion of recent cases, many of which are curable."

It is impossible not to participate in the

regret here expressed. The state of the lunatic asylums is everywhere

the same. In England and in Ireland, as well as in Scotland, they are

not only insufficient in number, but those which exist are clogged with

incurable cases, to the exclusion of numbers who by suitable treatment

in a well-managed asylum might be restored to health, and again become

useful members of society. The obvious if not the only remedy for this

state of things, would be, to establish subsidiary asylums for chronic

and incurable cases, in connexion with the ordinary asylums, which would

then be left free for the treatment of the curable, and for the

application of whatever medical science could devise in mitigation of

one of the heaviest afflictions with which humanity is visited.

If in any case the relief afforded to a poor

person is deemed by him to be inadequate, the 74th section of the Act

provides that he may "lodge or cause to be lodged a complaint with the

board of supervision," which is without delay to investigate the same;

and if the complaint appears well founded, the board is to record, a

minute declaratory of its opinion that such poor person has a just cause

of action against his parish, which will entitle him without further

proceedings "to the benefit of the poor's roll in the court of session."

The board of supervision is thus made the channel through which the

person complaining of inadequate relief has to seek redress, and it

became the duty of the commissioners therefore to afford every facility

for the transmission and adjudication of such complaints. Forms of

application were accordingly prepared, and placed in the hands of the

inspectors of the poor, with directions to deliver one to every poor

person on the parish roll who might demand it, and also if required to

fill up the form in any terms the applicant might desire. After the form

has been filled yip with the statement of the applicant, it is to be

delivered open to the inspector for him to insert such remarks thereon

in the way of explanation as he may think fit, and it is then to be

transmitted to the board of supervision for decision or further inquiry

as may be judged expedient.

When the information thus obtained led the

commissioners to consider that the relief complained of was inadequate,

the case was remitted to the parochial board for reconsideration.' If

the relief was then adequately increased, the ground of complaint was

held to be removed; but if the relief was not increased, or was not

adequately increased, the parochial board was then called upon to state

the grounds on which they held the relief to be adequate; and if they

failed to do this, or if the grounds stated were deemed insufficient, it

was then intimated to them that unless the relief were adequately

increased, a minute declaratory of the board's view in the matter would

be recorded against them. In all the cases thus remitted to the

parochial boards, the commissioners have, they say, been satisfied by

the information furnished to them, that the relief complained of was

adequate, or that the additions subsequently made thereto were such as

to remove the grounds of complaint. It is ,then with great propriety

remarked, that these decisions on complaints of inadequate relief, not

only affect the comfort and well-being of the applicants, but must also

influence the scale of relief to the poor generally; and the

commissioners declare that they have felt the full weight of this

responsibility, and have given the most careful consideration to the

cases that have come before them. "To have sanctioned illusory or

inadequate relief, would (they say) have been unjust to the poor. To

have exacted more than needful sustentation, would have been unjust to

the ratepayers and to the independent labourers, and injurious to the

community." The

condition and habits of the people, and the cost of their ordinary

subsistence, are so different in different parts of Scotland, that no

unvarying rule could be laid down for adjusting the amount of relief. A

weekly allowance which would be fully adequate in the Highlands and

Islands, would be inadequate in the southern counties. Even in the same

parish, the commissioners observe, it rarely happens that any two cases

are precisely similar; and they are satisfied therefore, that the only

safe course is to consider each case with reference to its own peculiar

circumstances. But although it might be impossible to fix any one

standard of adequacy for the whole country, it was necessary to

endeavour to ascertain the cost of subsistence in the different

districts, so as to enable the commissioners to judge of the adequacy or

inadequacy of the allowances in case they should be complained of. After

much anxious deliberation and inquiry on this point, they have, they

say, "come to the conclusion that the safest guide to a right estimate

of what constitutes 'needful sustentation' in any parish, is to be

derived from a knowledge of the earnings on which industrious labourers

are able, in that parish, to maintain themselves and their families

without parochial aid;" and they add, "that it would be a fatal error,

even in Scotland, where such persons only as are incapacitated by

physical or mental disability from maintaining themselves are entitled

to parochial relief, to make the condition of the pauper more desirable

than that of the independent labourer"—a proposition which no one will

be disposed to controvert. The number of cases of paupers complaining of

inadequate relief which had come before the board of supervision, down

to the date of the Report, was 597,—of these 303 were dismissed on the

information contained in the schedules, and 94 after communication with

the parochial boards. In 182 cases remitted to the parochial boards, the

allowances were so far increased as to remove the ground of complaint;

and 18 cases remained undisposed of. The discontent which led to the

transmission of so many complaints was, the commissioners say, "not

caused by urgent destitution, and still less by any unfavourable change

in the complainants' condition since the new Act came into operation,

for their condition had been greatly improved; but was to be attributed

chiefly to the exertions of certain persons to excite discontent amongst

them, and to the extravagant expectations that had been raised of the

advantages which the Act provided for them."

According to a return of the applications

made by poor persons to the sheriffs in the several counties, under the

73rd section of the Act, on account of their being refused relief, it

appears that the entire number of such applications during the fifteen

months in which the new law had been in operation, amounted to 456, of

which 184 were from the counties of Ross, Sutherland, and Caithness.

Upon this the commissioners remark, that where the change was greatest,

the applications would necessarily be the most numerous, and the labours

of the sheriffs are said in some instances to have been very

considerably increased thereby. The duty of deciding moreover, the

commissioners observe, must often be painful and perplexing. Where the

applicant is both wholly disabled and wholly destitute, a parochial

board can hardly fail of at once affording the relief which there is

then no -ground for refusing. But it is in cases of doubt as to the

applicant's right to be placed on the roll, that the sheriff is likely

to be applied to, and these are generally cases of partial disability,

or partial destitution, in which it is obvious that questions of•

extreme nicety must occasionally arise, in ascertaining the precise

point at which an individual may have become entitled to relief. The

commissioners suggest what would seem the right method. of solving such

questions, by remarking, that "were poorhouses universally established,

they would afford a ready means of testing the exigency of such claims;"

and they support this suggestion by declaring that in parishes where

poorhouses exist, the same difficulties have not been experienced in

dealing with applicants of whose claims doubts were entertained by the

parochial board, an offer to receive an applicant into the poorhouse

having been held to be sufficient to justify the refusal of other

relief. This testimony as to the insufficiency of individual judgment,

and the importance of an established test, for determining the claims of

applicants for relief, is of great value, coming from such a quarter;

and we may presume, can hardly fail of leading eventually to an increase

in the number of poorhouses, the want of which thus appears to be

already felt.

Accuracy and uniformity had not yet been established in registering the

poor who were in receipt of relief, nor in the accounts of the

expenditure for that purpose; but according to the best returns which

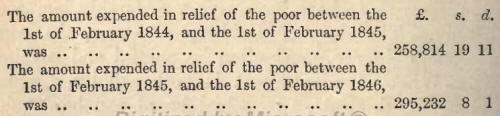

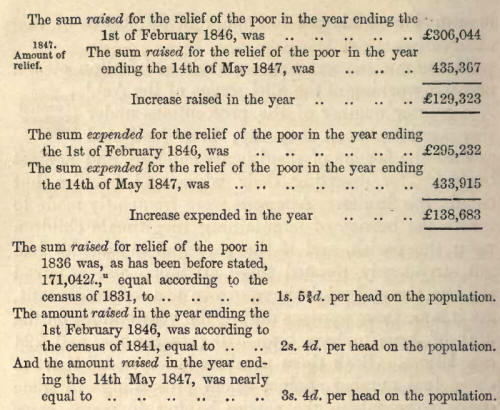

the commissioners could obtain from the several parishes,

The shortness of the time since the new Act

came into operation, and especially since arrangements were made in

accordance with the 54th section, for placing certain funds at the

disposal of the kirk sessions, made it impossible to obtain separate

returns of the expenditure by that body, and the whole amount expended

on relief of the poor, from whatever source derived, is therefore

included in the above statement.

It appears from returns obtained in 1843,

that the money raised from all sources for the relief and management of

the poor in Scotland, amounted-

In February 1846 the amount expended is

above stated to have been 295,232l; but the amount raised in that

year was 306,044l, being, as compared with 1836, an increase in

ten years of 135,002l., or nearly 79 per cent., upwards of a

fourth part of which increase had, it is to be remarked, taken place in

the last year.

The annual value of real

property in Scotland, according to returns laid before parliament in

1843, was 9,320,794l.

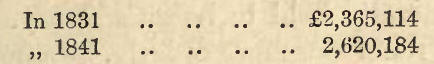

The population of Scotland at the periods of

the census in 1831 and 1841 was-

Thus exhibiting an increase of population in

ten years equal to 10.7 per cent.

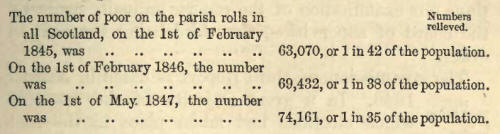

The number of poor on the rolls of all the

parishes for the year ending 1st February .1845, was 63,070, or about 1

in 42 of the population. For the year ending the 1st of February 1846,

the number on the rolls was 69,432, or about 1 in 38 of the population ;

but the imperfect mariner in which the parish rolls were kept, deprives

these numbers of any pretension to exactitude.

The commissioners conclude. this their,

first Report with the declaration, that they are deeply impressed with

the importance of the duties assigned to them, and the weight of the

responsibility involved in the administration of the Poor Law. They have

however, they say, felt that the responsibility did not rest with them

alone, but was shared by the parochial authorities of the country; and

they bear, testimony to the honourable and humane spirit in which the

heritors and parochial boards generally, have endeavoured to give effect

to the provisions of the 'Act for the Amendment and better

Administration of the Laws relating to the Relief of the Poor in

Scotland.' Such was

the first Report of the board of supervision, of which it has been here

endeavoured to give the condensed substance, and on all material points

as far as possible in the words of the Report itself; for it was felt to

be important that in a matter so peculiar and beset with so much

difficulty as the new Scottish Poor Law, the views of the commissioners

charged with the duty of superintending its introduction should be so

stated, as to leave no doubt of the grounds of their proceeding in any

case, or of their decision upon any point, whether of practice or

principle. The

first year's experience of the working of the new law, was generally

held to be satisfactory. The administration of relief was more orderly,

its amount approximated more nearly to the wants of the recipients, and

the charge was more equally spread over the whole community. The means

of further improvement had been provided for by the organisation of

parochial boards with inspectors of the poor, and by the various

regulations promulgated by the board of supervision—all tending to the

establishment of one comprehensive system throughout the country, varied

only in its application by the different circumstances of the districts

where it had to be applied. For the details of such application in

carrying out the law, and for the results which ensued, we must turn to

the second and subsequent Reports of the commissioners.

The second Report of the board of

supervision was made in August 1847. The period was one of much distress

and difficulty, owing to the almost universal failure of the potato

crop. Some details of this calamity, as it occurred in England and

Ireland, are given in the Histories of the English and Irish Poor Laws.

In Scotland the pressure caused thereby was exceedingly severe,

especially in the Western and Highland districts, which were again

reduced to a state similar to that which occurred in 1783. The Report

states that "the failure last year of the potato crop which had hitherto

furnished probably about two-sevenths of the food consumed by the

population of Scotland, and the high price of every description of

grain, demanded increased allowances to the poor." As soon therefore as

it was ascertained that the failure "had been almost universal and

complete," the commissioners called upon the parochial boards to

consider the propriety of increasing the allowances, and recommended

that the increase should be made in the form of a separate extraordinary

allowance in food, rather than an increased allowance in money. They

were aware, they say, that in certain of the poorer parishes, advantage

might be taken by dealers to exact exorbitant prices, or to adulterate

the food; and they therefore recommended the parochial boards of such

parishes to lay in stores of meal on their own account, from which the

extra allowances should be issued to the poor: but as the commissioners

had no means of ascertaining in what parishes a regular supply of food

at fair prices could be safely relied upon, they left each parochial

board to the exercise of its own discretion as to laying in stores, or

trusting to the ordinary course of trade for a supply.

The Appendix to the Report contains long and

minute statements made by officers whom the board of supervision, on the

failure of the potato crop, had sent to the distressed districts of the

western Highlands and Islands, with directions to visit the several

parishes, and examine into the condition of the poor; and it appears

from these statements, that although the labouring classes endured much

privation in most of the parishes, "the poor who were dependent on

parochial relief had been provided with the necessaries of life at least

as amply as in the most abundant of former years." The commissioners

also remark, that "taking into consideration the shortness of the time

that has elapsed since any systematic attempt has been made to give

effect to the legal provision for the poor in those districts, and the

very severe test to which the efficiency of the law and of the machinery

by which it is to be carried out have been exposed during the last year,

they think they are justified in expressing a confident hope that the

recent statute will be found adequate to accomplish the benevolent

objects contemplated by the legislature." They further express their

satisfaction at being able to state, "that after a careful investigation

they have been unable to discover any case in which it can be clearly

established that want of food was the immediate cause of death"

doubtless a subject of gratulation, as the reverse was to be expected

under the very trying circumstances of the period. But considerable

mortality did nevertheless ensue, want and disease having on this as on

other occasions maintained their accustomed relations of cause and

effect; and the commissioners express their regret at having "to report

the death of several very efficient inspectors and assistant-inspectors,

and more than one medical officer, from fever caught in discharge of

their duty amongst the poor."

The Scottish Poor Law, we have seen,

excluded able-bodied persons, that is in fact all the class of

labourers, from participating in its benefits, or availing themselves of

its protection in seasons like the present. It is true that famine, or a

failure in the usual supply of food, is an event so far exceptional as

scarcely to admit of being provided against by any description of Poor

Law; but like other visitations it has its degrees of severity, and the

sufferers under it have their different claims for sympathy and

assistance. To exclude formally and entirely, whatever might be the

circumstances, any one class or section of the people, whilst all

requisite support is furnished to another section, does not seem to be

consistent with justice, and can hardly be defended on the score of

policy. The failure

of the potato crop was known so early as the month of August in the

preceding year. The failure was very general, but in the western

Highlands and Islands where the potato constituted the chief food of the

people, it was nearly entire, and the distress was there proportionally

great. The board of supervision, as already stated, took steps for

securing a sufficient supply of food for those of the poor who were

legally entitled to relief ; but with regard to the rest, for all were

poor, assistance had to be sought elsewhere. Government was early

applied to, and an experienced cornmissionary was sent to ascertain the

state of things, in the western districts, and to organise the means for

supplying the wants of the population. Extensive inquiries were likewise

instituted into the state of the crops, and the condition of the people,

in other parts where a dearth of food was apprehended. The distress was

referred to with expressions of "the deepest concern" in the Royal

speech on the assembling of parliament, and in answer to inquiries

afterwards made, the home secretary stated that in order to mitigate the

distress, government had made advances under the Drainage Act of last

session (9th and 10th Viet. cap. 101), which in their results were

highly beneficial, increasing the value of the land to the proprietors,

and affording extensive relief to the distressed labourers. The

government had moreover, lie said, established depots for the sale of

food, one at Tobermory and one at Skye, in addition to which

commissariat officers had been sent in government steamers to make

inquiries, and to give such assistance as was necessary. These measures

had, he believed, been the means of supplying the people of those

districts with food, who otherwise would have been in want of the

necessaries of life. Grants had moreover been made in a few instances

"to meet local subscriptions, and to relieve distress, where the

Scottish poor law had been found to be inefficient; and lie hoped that

by these means the severity of the calamity in Scotland might not only

be mitigated, but that by the exertions of the landed proprietors, who

showed every disposition to meet the misfortune, Scotland would be

brought safely through the present crisis. [q See Sir George Grey's

speech on the 1st of February 1847, as given in Hansard. I have examined

the voluminous correspondence which took place at this time between the

government and various parties in Scotland, and extracts might be given

as in the case of 1783 (see ante, p. 117) showing the extent of the

distress, and the sad condition to which the people were reduced, in the

Highland districts especially; but all that is necessary for our present

purpose seems to be comprised in the speech of the home secretary, the

substance of which is here given. "The British Association " remitted

77,G831. for relief of the distress in Scotland, that being one-sixth of

the amount of subscriptions received by them. The other five-sixths were

appropriated to Ireland. The conduct of the landed proprietors of

Scotland on this occasion was generally admirable. They appeared to feel

the duties appertaining to their position, and promptly and liberally

responded to its claims.]

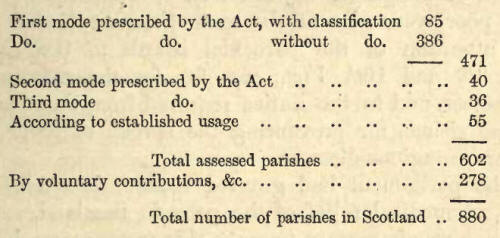

Of the 880 parishes existing in Scotland,

the number which, down to the end of June in the present year, had

resolved to raise the funds for relief of the poor by assessment was

558; of these 431 were assessed according to the first of the three

modes prescribed by the recent Act, 37 according to the second, 34

according to the third, and '6 according to local Acts or established

usage; whilst 76 of the parishes assessed according to the first mode,

had classified lands and heritages in the terns of the 36th section of

the statute. The commissioners had sanctioned changes in the mode of

assessment at first adopted in several of the parishes, and also in

regard to the classification; and on a review of the number of parishes