|

Out at Sea.

We are now fairly over

the bar and once more launched on the vast Atlantick. [The George,

Captain Deans, sailed for Glasgow, via Lisbon, on November 10, 1775, as

recorded in the log of the Cruizer. The only contemporary reference to

Miss Schaw's departure is contained in a letter from Mrs. DeRosset to

John Burgwin. Mr. Torn Hooper," she writes, "went to Scotland in a

vessel with Miss Shaw and Miss Rutherfurd, on the way to England" (James

Sprunt Historical Monographs, no. 4, p. 28).] We have every reason to

hope a prosperous Voyage, and every thing has been clone to render it an

agreeable one. I know not if I ought to rejoice that we have Neilson for

our companion, as want of health has forced him to leave the continent,

and what sits heavier on his spirit, his friend Govr Martin, at a time

when he wishes to be near him, but in his present state of health, must

be a trouble not an assistance. I have been greatly obliged to that

Gentleman, ever since he became my acquaintance. His attention has been

that of a kind brother, and my gratitude is that of a much obliged

sister. Should he get soon better, he will (as far as possible) supply

my brother to me on this voyage. His conversation is entertaining and

instructive, and if he recover his health, I hope he will recover his

spirits and gain the fortitude necessary to his present situation, which

is truly a hard one, as he had very considerable emoluments in America,

and still higher prospects, which I fear will not be his again for a

long time. But he is a vast philosopher and often uses your expression

"it will be all one a hundred years hence."

Mr Rutherfurd and my

brother Bob saw us over the bar— a bitter parting, I do assure you, it

was on all sides; poor Mr Rutherfurd with all his family, and my brother

with a lately found and much loved sister. I fear the Adieu is for ever

and for ever. Poor Fanny was hardly able to support it, nor has she vet

recovered from the shock. I should think less of myself than I do, did I

not feel severely for those I leave behind; tho' in hopes of soon

meeting Objects dear to my heart as life; objects indeed that can only

endear life to me. Our schemes for the present are frustrated, vet let

us not think we are the sport of fortune. Dark as my fate seems I

sincerely believe that mercy ever triumphs over evil, and that a

powerful hand controls what we call fate. To him then let us submit, and

only pray for that fortitude, whose basis is trust in his goodness and

omnipotence. I do not suppose this voyage will furnish any thing new,

but if it should, it is not in my power to keep a journal of it, as my

brother begged my stock of writing-materials, there being none to be had

for love or money. The few sheets I now have I will keep, till we arrive

at Portugal, when I will begin again to write, not to inform you of what

you know so well already, but a journal of my own thoughts, ideas and

apprehensions, where every thing is new to me.

Mr Neilson is very ill;

Miss Rutherfurd not very well; the boys in good health, as I am. We have

brought many pets, of which number is the bear. We were afraid he would

join his brethren of the congress, and as he has more apparent sagacity,

than any of them, he would be no small addition to their councils. Our

Captain is a plain, sensible, worthy man, plays cribbage and backgammon

dexterously, and when our poor Messmates are better, we are provided for

Whist. Our cabins and state-rooms are large and commodious, our

provisions excellent and our liquor tolerable; but I long for a drink of

Scotch two penny, and will salute the first pint-stoup I meet and kiss

the first Scotch earth I touch. A weight however hangs on my heart.

Adieu, you shall hear from me first opportunity. Adieu, may our meeting

be happy. Decemr 4th

1775 Aboard the George in the bay of St Tubes.

Between ten and eleven at night, we were

hailed by a pilot-boat, which the Sailors called a bear-cod, as it

exactly resembles one. By the Master we were told that we were then just

opposite to Lisbon, and tho' it was extremely dark, I was directly for

going aboard the boat, and making for the place, where my friends all

resided, but was not a little surprised to be informed, that if the

boatman carried me ashore, he would be hanged for his pains, and that it

was not easy to answer what would become of myself. This brought on an

explanation of all we must go thro' before we landed, and I was most

terribly mortified that tho' so near our port, it would yet be several

days before I could step on terra firma. The Capt also recollected that

we had got no bill of health, and we dreaded the horrours of a

Lazaretto; but Neilson happily was the very officer, from whom we should

have had our certificate, so having the seal of office in his trunk, he

made no scruple to antedate it a month and some days, and to write Out a

long certificate in very handsome Latin, which our faces bore witness

to. Our fears of a

quarantine were at an end, and we slept that night in quietness; as we

hoped to be in port by breakfast. But the wind coming against us, it

took up most of the day to get forward, and we did not get on the coast

till the afternoon, which luckily proved very fine, and here I had the

pleasure of viewing an Italian sky, the beauty of which you have so

often described to me, and at which I looked with uncommon delight,

because it brought back to my memory, what you have said to me on this

and many other Subjects. Nor was I entirely engaged with the heavens;

the earth claimed part of my attention, and the hills, the rocks, the

dales, all joined to please an eye that had been long deprived of such

delightful variety, and confined to a dead level or nodding black pines

equally disagreeable. The verdure just now is most lovely and meets the

eye every where. Tho' this is by no means the sort of country I took it

for, as I have fancied to myself a West India Island as large as a

world, I was vastly pleased to behold the noble buildings as we sailed

along the coast, till I was informed by our pilot, that they were, in

general, bastiles—oh sound of horror and fear to a British ear.

At last we reached the hay, where we

anchored within less than a mile of the Town of St Tubes. The scene

altogether was very lively and animating, particularly when joined to

the idea of being once more in Europe. The evening was fine, the sun

gilding the horizon and giving additional beauty to the green hills. The

sky was placid and serene—above fifty ships were lying at Anchor, and

above a hundred boats engaged in the sardine fishing and chanting

Vespers. The town was full in prospect and many windmills going above

it, which I think a very cheerful object. The coast is extremely bold

and the hills and high grounds, covered with wheat or pasture, looked so

fresh that they perfectly cheered the senses.

But while we were busy admiring this

pleasing scene, a boat approached, which was presently known to be from

the custom-house. There were three or four tide-waiters in her, the

sight of whom set our Johns to such cursing and muttering, that I could

not conceive what ailed them, till the Capt told me these vermine were

come to take their Tobacco, and would not leave them a single quid in

their pouches. I could not wonder at their distress or rage on this

occasion, nor be offended when they declared that America was dam—lv in

the right to keep clear of these land rats. These however were only the

guards come to prevent any being carried ashore. The others came in the

morning. We have got figs, grapes and most charming wine on board, at

which we are sipping at no allowance. I am charmed with the bells—there

goes one just now as like our eight o'clock bell as it can be—clink,

clink-dear me 'tis heartsome. Good Night.

There has been a general search for Tobacco,

our Johns laid down there quids with a sneer that fully convinces me

they have not lost all their comfort that way. Tho' the people who came

on board made but a scurvy personal appearance, I found a vast

difference between their manners, and those in the same station at home.

They were actually distressed when they saw Ladies and made a thousand

apologies. As Mr Neilson speaks every European language, we were

informed of whatever we wished to know thro' his means. But tho' he made

the tour of Europe a few years ago, he never was in Portugal, so is a

stranger to their customs. He is particularly distressed about getting

ashore, which, these people say, cannot be for three or four days. I

plainly see he is to take such a charge of us, as will tease his

life—Lord help him, he little knows how perfectly easy I am, and more

inclined to laugh than cry at the little accidents we meet with on this

journey. Oh my friend! that I had no more to distress me—but let us not

repine nor quarrel with the wise economy we ought to adore. 'Tis in our

own breasts that the events of fate must take their colour. The

reception they meet with and the turn they take there, constitute them

good or evil. One thing I am at least sure of, that if you are happy, I

never can be miserable.

I was interrupted by a message informing me

that the officers of health and of the holy Inquisition were just coming

aboard—also that the Proconsul begged the honour of waiting on the

English Ladies. Tho' the Inquisition has now lost its sting, there is

still an horrour in the sound, and, Miss Rutherfurd says, I grew pale at

the name. I had no reason however. In place of a stern Inquisitor, came

a smiling young Priest, who, I fancy, would render penance pretty easy

for some of us, were he chosen Father confessor properly. Our healths

were taken for granted, and our chests tho' opened, were not searched.

Oil my chest, I observed a piece of excellent self-attention in MIS

Miller, who had been told, that if a Bible was found, the person who

owned it, would be sent to the Inquisition. She had one in folio, which

she had transferred to our chest, and taken no care to conceal it.

However it was taken no notice of. The proconsul spoke very good French,

and our priest conversed with Mr Neilson in Italian. They drank tea with

us, and after making the Capt sign to a set of most curious articles for

himself and his crew, they left us at full liberty to go ashore when we

pleased, and to carry our trunks (which they marked) unmolested by

further search. I made Neilson translate the Articles signed by the

Capt, mate and himself, some of which were as follows. That the said

officers or none of the crew shall insult any female they chance to

meet. Item, that they shall take off their hats to the clergy, and not

affront them in any way; that they shall kneel at the elevation of the

host; that they shall in no way insult the cross, whereever set up, by

making [water], but however urgent their Necessities may be, shall

retain the same, till at a proper and lawful distance. Many more equally

important were set down and signed.

Neilson, who went on shore with our

Visitors, has returned and informs us he has by their means got us

excellent lodgings, and that we are to eat meat to morrow on shore, tho'

this is a season of strict fasting. He has given us a most ludicrous

account of the Lady who is to receive us; a Senora Maria, who has said

so many handsome things to him, that he is quite afraid of her. He has

told her however he is married, and his wife comes ashore with him. I

fancy he found this necessary, and I am to take him under my protection.

They assure me the packet will sail from

Lisbon in a few days, and I will get this sent you. You will see by my

writing, we had a good voyage, tho' I forgot to tell you so. We were

just thirty two days, the blinds were never up, nor were we incommoded,

tho' we had a fresh breeze thro' the whole Voyage.

We dined yesterday with Senora Maria, a

squat sallow dame between forty and fifty, but such an Amarosa in her

manner, that Neilson required the presence of his supposed wife to save

him from the warmth of her caresses, which, to say the truth, she

bestowed on us all, embracing and clasping us till we were half

suffocated. But this was not the worst of it: she brought her maid to

pay her compliments. She was just Don Quixote's Maratornious [Maritornes],

with her jacket and rouff-eye; have not seen such an animal. She would

measure half as much again round, as from head to foot. Her bushy black

hair was frizled up, which with her little winking eyes and cock-nose

made a most complete appearance. I trembled for her embraces, as the

effluvia of the kitchen were very strong, but happily she was more

humble than her dame, for she squatted down and clasped us round the

knees, kissing our feet, which we permitted her to do without raising

her to our arms, as it seems we ought to have done. Senora took much

pains to inform us she was no publican, only kept a house of

accommodation for her friends, in which number she did us the honour to

consider us. This would have surprised an Englishman, but I, who had

been used to such friendships, thought it not stranger than that of the

bridge of Tay, with many more in your country, where I have been treated

as a friend with very little ceremony, and paid very decent or rather

indecent bills for meat and drink, of which I had the smallest share.

Dinner over, we went to view the town, which

has been once magnificent, but is now almost entirely a ruin, partly

owing to the dreadful earthquake, and partly owing to the still more

horrid effects of despotism. Here I beheld the remains of the palace of

the Duke de Alvara, a most noble ruin. His fate you know well, and I

dare say we both join in thinking that he and his son the Marquis

deserved every severity; for it is past a doubt, that they made an

attempt on the life of their sovereign—a crime that admits of no

palliation. Yet as Voltaire most justly observes, there is no crime

however great, but we lose sight of, when the punishment is extended

beyond the limits of humanity. Thus the memory of these two parricides

would have been held in utter detestation, had they alone suffered

death; but when we see the venerable Dutchess, the two amiable youths

not vet eighteen years old suffering the same dreadful fate, tho'

entirely innocent, nature revolts, and will no longer term it justice,

but diabolical barbarity. Nor does it appear less shocking to find the

impotence of power extend to objects incapable of feeling or

understanding punishment—one infant daughter rendered infamous and shut

up in a convent to [serve in] the lowest offices; ashes strewn in the

air; one palace torn down and the ground salted, another entirely

ruined, tho' the walls yet remain so far as to let you observe how great

this unhappy family, once were, and whose fate is silently regretted by

their country. You know the exclusion of the Jesuits followed this

affair, and with them fell the power of the Inquisition.

We visited several churches, which are now

decorating for Christmas—the Virgin is dressing out, and is sometimes

very pretty, tho' at other times most gloriously ridiculous. Some of the

churches are truly fine, but the images are in general paltry and no

fine paintings in any of those I have seen. But we have an invitation to

a convent of Missionaries to morrow, where they tell me every thing is

noble, and they are rich tho' beggars by profession. It will not be easy

for the sailors to observe strictly the articles of not affronting the

cross, for they [the crosses] are so close on each other, that it will

hardly be in their power to keep clear of offence. Indeed the profusion

of emblems of the most sacred of all subjects shocks me greatly. You

find it over the doors of places for the vilest uses. You see the most

horrid violation of it, wherever you turn your eyes, and one would think

it was set up by Turks or Jews, as a standing ridicule and reproach on a

religion they despised and disbelieved. It is not here I would be

converted to the Catholick faith, as it is no better than a puppet show.

I must tell you an anecdote of our hostess

Maria. As she carried us thro' a very disorderly and dirty house, we at

last arrived at a sort of lumber room, where stood a large cloth press.

She put on a solemn look, and bade Neilson inform its we were in her

private chapel, that she was not rich, but what she had to spare she

bestowed on her God. I approved of the object of her liberality, but

could observe nothing in her chapel worthy the acceptance of a much

lower person. But on opening the above mentioned press, we were struck

with a view of the Virgin and her son in figures, not much above the

length of my middle finger, attended with a croud of Lillipu- tian

saints, who were gayly dressed, and stood on each side in decent order.

A folding up altar was then let down, on which was displayed every

utensil necessary for devotion in minature, the whole making a very

pretty baby house. Senora Marla kneeled and crossed herself most

devotely, in which the good breeding of Mr Neilson accompanied her. I

made a slight obeisance, but Fanny viewed the whole with the utmost

contempt. No sooner was it shut up, than the Vivacity of Senora

returned, and pulling out the drawers under this model of a Romish

Church, she displayed her Wardrobe, of which she was not a little vain,

then making us a present of some artificial crosses, she led us to the

further corner of the chapel, where was fitted up a great number of

wicker baskets for sale, extremely pretty, of which we purchased

several. Were I sufficiently in cash, I could buy many things here

vastly cheap. Some money I will venture to lay out; as at Lisbon I am

sure of credit. But were not that the case, I should feel a pang every

time I unlocked my little cash-chest, which contains a large sum for a

poor refugee, and of which I never dare lose sight, having no very high

idea of Fortugueze honesty. The bed-chambers at Maria's were so dirty

that we could not stay in them. Neilson indeed was so resolute to have

us go on board to sleep, that I could not help thinking, he was afraid

to be from under my pro/cc/ion at that season [that is, at night], when

I could not so cleverly keep up the character of wife.

We leave St Tubes to morrow morning, and are

to proceed to Lisbon—but tho' no great journey, the manner of our

travelling has been a work of no little trouble to Mr Neilson, whose

goodness and attention knows no bounds. What must have become of us

without him? I think it would have been impossible to have gone on. Yet

I am often vexed at his anxiety, for as he is hurt by our smallest

inconveniency, he is for ever uneasy, as such accidents must constantly

occur in our present situation. Our mode of travelling has been a source

of great distress, as no other carriage was to be had, but that of a

pack-saddle fixed on the back of either an ass or a mule. For my part I

had just been contemplating the ease with which a set of market women

was moving along and admiring their mounterrara caps, when he entered

the room, and in the greatest vexation told me, he believed I would not

get to Lisbon. On being informed of the wherefore, I assured him that

should not prevent my Journey, as I thought the pack saddle as pretty a

method of travelling as any I had seen. What! Miss Rutherfurd and me on

pack saddles! Be it ever so easy a method, he would not submit to see us

in such a style. I begged him to consider that we had no dignity to

support at St Tubes, and that the disgrace of the pack saddle would he

entirely washed away before we got to Britain. Nothing could reconcile

him to it however, and telling me adventures did better in theory than

practice, he went off with a priest, who soon procured him the calash of

a noble Lady, who is banished from court to this place, for having

privately married without the King's consent a brave officer, who is

confined in one of the Neighbouring bastiles, and it is supposed he will

be put to death. As her relations are very powerful, she has offered to

shut herself up in a Monastery, and make over all her fortune to the

court, if they will pardon him. Oh Britons, Britons, little do you know

your own happiness!

This affair settled, we went round the

churches, which are this day finished. The new dresses of the Virgin are

all in the British taste, white and silver, and blue and silver are the

favourites. But at one church she had on a tie-wig—but why am I

describing to you what you are so perfectly acquainted with; yet allow

me to say that I could not have believed it possible to have turned the

plain, the noble and rational worship ordained by its blessed Author

into such a farce, as is acting here at this moment, nor can I believe

the Actors are not in general laughing at themselves. We have made

several acquaintances with priests, whom I like very well, and one of

them is so much pleased with our company, that he has not found the way

to his convent since our arrival. He stays at a Mr G—'s, an English

merchant, who politely carried us to his house, and introduced us to his

sister, who tho' married to a Portugueze husband, takes all the

liberties of a British wife. We have found her however a very good

companion, and as she knows every body are much the better for her. Our

pre Francis is a jolly round- faced, round-belly'd father in grace. A

certain young American engages however his attention at present as much

as his holy Mistress; not that he neglects his duty to her, far from

it—he gets up every now and then even from cards, and running to a lamp

and Mass-book, which lie ready, he repeats his Ave Marias as fast as

possible, and then returns to the object of his present adoration, and

begging her pardon, shrugs up his shoulders, saying these things must be

clone. This father, whose vows tie him down to poverty and

mortification, wears his robes round his middle very gracefully, his

cowl hangs back in a careless manner, and shows a jolly, comely

countenance. He cats monstrously and drinks a tumbler of wine to wash

down every three or four mouthfuls, and by the time dinner is over, is

fit for any frolick you please. Yet he has a sort of decency of manner,

and in the midst of a very foolish conduct, has a sobriety in his looks,

which is not the case with them all.

One in particular at whose convent we

yesterday paid a visit, is a perfect light-headed Oxonian. He was so

transported at seeing us at the convent, that he lost sight of his

character, fell on his knees and embraced ours, to our no small surprise

and confusion. He then ran for the superior, with whose looks I was

indeed quite charmed, and involuntarily paid him that respect, I could

not believe any of his order could have deserved. Nay, so much reverence

did this old man of seventy nine inspire, that I seriously begged his

benediction, and found myself affected by the benevolent solemnity with

which he bestowed it on me. Our gay priest provided a collation for us,

which he produced and placed without ceremony on one of the low altars

that adorned this church, which is indeed a very fine one, and has some

good paintings and images, particularly one of our Lady of Sor- row,

placed under a large crucifix, which I think as affectingly beautiful as

the fancy of any Artist could produce. But the image on the cross,

appears more calculated to inspire horror than either love or devotion.

Nor are you ever shown this amiable pattern of all human perfection from

his childhood, till he appears in the attitude of agony and extreme

misery. This is doubtless owing to the dark superstition peculiar to the

people of this country, where religion is held as a whip over slaves,

and every individual has a court of Inquisition within his own breast.

They figure the merciful father of his creatures, dark, gloomy and

inexorable as the first Inquisitors. That this does not prevail in every

Roman Catholick country is certain; of which the fine paintings I have

seen copied are a proof, where we see that divine figure often

delineated in the act of pardon and mercy, with a countenance that

inspires the beholder with love, gratitude and adoration—in those there

might be danger, but in nothing I have seen here.

We slept last night in an apartment in the

Duke de Alvara's palace. Luckily we did not know where we were till the

morning, otherwise that most unfortunate noble family would have haunted

our dreams. Tho' the place where we were is part of the vast building,

yet it seems to have been only apartments for the domesticks, as it

enters differently from the palace, but has been itself most

magnificent, and is now occupied by the English Gentleman, whom I before

mentioned, and he is making it very neat. But the grand apartments where

the family resided are under the sentence of infamy, the windows built

up and no one suffered to enter. The earthquake did it no harm, and

there still remains a noble balcony covered with lead round the whole,

which is longer than our Abbey of Holyrood house. Also the ruins of a

vinary at least a thousand feet in length, where they had grapes all the

year. The gardens and fish-ponds have been noble and extensive, they are

now turned into vineyards, and let out to tenants. Tho' treason is a

crime of so high a nature as to admit of no palliation, yet we must

regret that such a family committed a crime to deserve such punishments.

Adieu, till I write from Lisbon, which I certainly will the first

packet. I have just got a letter from Mrs Paisley in return to one I

wrote her. It is impossible to say whether her pleasure or surprise is

strongest. Her affection however is most expressive, and I am sure my

heart feels it.

Lisbon Decem the 20th

We got here last Night thro' many

adventures, and are now as happy as the most amiable and most

affectionate of friends can make us. But I will go on in proper form and

begin with our journey, which proved a perfect comic- tragedy, and I was

often at a loss, whether to cry or laugh. We set out in the calash of

the noble Lady, which was really • neat one, drawn by two excellent

Mules and conducted by postilion, whose head would be an object of envy

to the first Macaronie in Britain. But our excellent governor [Neilson]

was so happy at getting us properly accommodated, that he forgot to take

care of himself, and left it to a Muleteer to provide three Mules—one

for our baggage, another for a scoundrel of a chetsarona [cicerone] and

a third for himself, begging only that he might get a common saddle not

a pack one. He got a saddle indeed, but not a common one, for it was an

old French pique, that had not felt the air for fifty years, with a

rusty stirrup at one side and a wooden: box at the other to thrust his

foot in. The

muleteer placed the baggage on the best mule. Our chetsarona had the

next choice, while the old pique was placed on the back of a mule, which

to his natural perverseness had added the positive humours of at least

five and twenty years experience, and guessing we were about to ascend

the mountain, absolutely refused to move. In vain did his unfortunate

rider make his back resound with kicks; he was insensible to every

remonstrance. The day was shockingly hot, Mt Neilson had run about to

have every thing convenient for his female charge, till he had got a

return of his fever, with a violent head-ache. No wonder his philosophy

was staggered. His courage indeed was so far spent, that he was on the

point of yielding the Victory to his Antagonist, when the Muleteer came

to his assistance, and with three or four hearty blows of a cudgel

across the rump of his stubborn property, he thought fit to move at

last, but with the most untoward motion, and stopping every now and

then, till the correction was repeated, went off with a jerk, which made

our poor friend feel all the defects of the old saddle. This was a bad

remedy for a head-ache, nor was it mended by the noise of the bells,

which hung round the baggage mule, and which I insisted on having in

view, having no very high idea of the honesty of a Portugueze Muleteer.

A light-headed young Portugueze officer, being on the parade when we

went into the calash, took a fancy to attend us, tho' a Perfect

stranger, and observing Mt Neilson's distress, he politely begged to

have the honour of whipping up his beast. Neilson by this time was so

heartily tired, that he did not care if the Devil was to whip him up,

and readily accepted the offer, when the ridiculous creature began a

scampering round our carriage, mounted on a fine Spanish horse, smacking

his whip over the mule, and hollowing diable mizuiia, mizila. There was

no resisting laughing, in which the sufferer himself joined in spite of

his head-ache. I

was exceedingly vexed however at this accident, as it was likely to

deprive us of Mr Neilson's company the whole way, thro' a glorious

country, diversified beyond description, every now and then a noble

building attracting our attention, but of whose use or names we could

get no information, our postilion speaking only his native language, our

Chetsarona not come up, and our best instructor kept off by his

confounded brute and light-headed companion. How often did I wish for

my, brother who would have enjoyed this scene to the full, and rendered

it many degrees more agreeable to us by his judicious remarks. Quite

impatient, we at last resolved to leave the calash, and ascend the

remaining part of the Mountain on foot, which was now bccome so steep,

that it was all our mules were able to pull up the carriage. The whole

road was covered with mules and asses, carrying wine in skins to the

waterside. Mr Neilson found no regret in relieving his stubborn pad of

his burthen, and by the assistance of his arm, we got on tolerably, but

not without many stops, not only to breathe, but to take a survey of the

charming prospects that presented themselves to us on all sides.

As we advanced nearer the summit, we left

behind St Tubes, the sea, the shipping, the large salt-works, the fine

ruins, and a country beautifully green with corn and rich

pasture-ground. Before us we had the river, Tagus, with the town of

Lisbon and all the adjacent country on the opposite shore. On our left

hand we had a scene nobly wild and beautifully romantick. The mountains

presented us with rocks and woods, thro' which flowed many a rapid

stream, which fell down in noisy cascades thro' the valleys below. But

tho' these valleys boasted their cultivation and invited us to admire

vine-yards, orange-groves and olive orchards, yet that where Nature

alone held dominion entirely engaged our attention, and we traced the

wildness of the mountains, as far as our eyes could penetrate thro' the

trees or over the rocks. While we were making different observations,

Miss Rutherfurd said it recalled to her mind a description she had often

admired, that of the scene when 1)on Quixote met the unhappy Gentleman

deprived of his senses. We had all agreed in the justness of the

observation, when at the very instant, as if by design, the scene was

completed by the appearance of an unhappy wretch in the very situation

in which the unfortunate count is there represented. Tho' a deep valley

divided the two mountains, he was directly opposite to us, and so near,

that we both heard and saw him distinctly. He was almost naked, his hair

hanging loose about his shoulders, while the swiftness with which he

leaped from rock to rock too plainly indicated the situation of his

mind, and as he approached the precipice, I trembled lest he would go

headlong over. However he stopped just on the utmost point, and falling

on his knees seemed to implore us (with uplifted hands) in a

supplicatory voice, which however was soon converted into that of the

greatest wildness, and his actions were quite frantick. He beat his

breast, tore his hair, and by his gestures seemed to be imprecating

curses on us, after which with terrible cries, he returned behind the

rocks, and we saw him no more. We were vastly affected at this view of

the greatest extremity of human misery, and which our Chetsarona told

[us] he had been reduced to by the infidelity of a wife he adored; that

he had killed her lover, and taken refuge in the convent just before us,

but was soon deprived of his senses. However the fathers humanely took

care of him, tho' he often escaped to the woods and rocks. That every

female he saw, he took for his wife, and always at first addressed them

with softness, but soon with such rage, as made it very dangerous to be

near him.

We were so much affected

with this melancholy scene, that we walked in silence up the mountain,

and had reached the summit before we were aware, and found ourselves

just under the convent of Palmella, which gives its name to a very

pretty village just by, remarkable for a small pleasant wine produced on

the Valley and rising grounds to our right hand. Whether the hurry of

the former scene had prepared us to look with peculiar delight on one

that appeared the perfect valley of contentment, I know not, but it

certainly conveyed to the mind a strong idea of rural felicity; and the

same thought struck all our company. It was one continued vineyard, with

a number of hamlets scattered thro' it, the neatness of which could not

be exceeded, and the whole scene looked like humility and safety. A

nearer view might have shown our mistake. We left both the town and the

convent without stopping, tho' much pressed to take refreshnient. Our

mules however drank at an elegant marble fountain for the relief of

travellers. We got into our Calash, Neilson mounted his mule, which

seemed more reconciled to his rider, and descended the other side of the

mountain in perfect safety, and to my no small surprise, I found a

heather moor above three miles long, and at the end of it came on a

flat, very unpleasant tho' a cultivated country, and got to My-toe [Moitaj,

which is in the kingdom of Lisbon, about four o'clock. Our guide

conducted us thro' a narrow lane, where we saw wrote over a door an

Anlish hot for man and best. This we entered, but did not find it did

much credit to England. Our Chetsarona however had been aware of this,

and we had every thing brought with us for dinner, and found we had only

to pay for leave to eat our own meat.

The Tagus like our Firth can only be crossed

at the tide. Mr Neilson had secured the first boat for ourselves, and we

were just Stepping on board, when two or three men interposed, and told

us we were prisoners to the state and must return. Our guide took much

pains to assure us that it was nothing, but I by no means liked the

Adventure. We were taken to the house of a judge, who received us in his

Library, but seemed very little pleased with this interruption to his

studies. Tho' the regard paid to our sex by every man in this country

obtained us civility, our judge or rather jailor was a little spare old

body, wrapt in a great cloak with a woollen coul on his bald pate, which

however he uncovered, nor could be prevailed on to cover his head or

resume his seat, while we were standing, which we did, till Neilson was

carried off to the Governor, from whom a message came to let us know

that we were at liberty, but the Gentleman a prisoner. This favour I

absolutely refused, and declared I would remain, till I could send to my

friends at Lisbon for redress.

No sooner had Neilson left the judge than he

made us be seated, and I dare say he paid us many compliments, as he

accompanied all he said with a most obliging air. We under- stood he

offered us fruit, which however we did not accept, but returned bow for

bow in silence for above an hour, during which time, our postilion, our

guide and Muleteer had been under examination in regard to us, and had

given such answers as convinced the Governor, who fortunately was not an

idiot, that we had no design either on the King's or Marquis of Pombal's

life. Two men then came and took an inventory of our features, our

complexion, the colour of our hair, and made us take off our hats to see

we had not wigs. This being done, a certificate was attested and

delivered to Mr Neilson, and we were set at liberty. We were forced

however to pay no less than Nine shillings and ninepence a piece for

this certificate, and we had lost the tide and were forced to return to

our paltry inn, till the next arrived.

Now for the first time, since I set out on

my expedition, my temper fairly forsook me. The Night was cold and a

drizling rain had conic on. It was also so dark, that I lost all the

pleasure I hoped for on the Tagus. Tho' we had hired the boat entirely,

it was half full of dead hogs, fish and a variety of articles for

Market, and we were hardly set off from the shore, when the crew began

chanting their Vespers, and had the dead swine which lay by them joined

their grunts to the concert, it could not have rendered it more

disagreeable. But farewell, the Captain of the Packet calls, and is to

take charge of this, and one for my brother himself. Adieu, Adieu.

Friendship is a plant of slow growth in

every climate, and of so delicate a Nature, that the person who can rear

up a few, may think himself happy, even where he has passed his early

years and has had his most constant residence. Travellers in passing

thro' foreign countries have no right to expect friendship, and if they

meet its resemblance in politeness and civilities, ought to be perfectly

satisfied. But how much greater reason have I to be pleased, who have

met the real genuine plant, a heart that beats time to my own, and

enjoys all the happiness she bestows, and participates all the pleasures

and civilities that on her account and by her means are hourly heaped on

us. You cannot have forgot the lovely and amiable Christy Pringle. You

have heard me speak of her a hundred times, and never without the

sincerest regret for her absence. That affection, that began while she

was in the nursing, is not lessened, and has proved to me a source of

infinite satisfaction. Mr Paisley, whom she married some years ago, adds

dignity to the name of a British merchant, a title that conveys more in

my idea than that of Duke or Lord in any other part of the world. He

carries on an extensive commerce to the East and West Indies, the

African Islands, the Brazils and indeed to every quarter of the globe.

His success has been what he justly merited, and I believe he is not now

second to any in our British factories. He lives with the Magnificence

of a prince and the hospitality of an English merchant. He is a

French-man in politeness, which his benevolent actions daily show to a

number of obliged and grateful connections, who by his means are put in

the way of becoming independent and happy.

We were received by him with that openess of

manner, that did not suffer us to feel we were strangers, and he soon

gave us every reason to think ourselves at home with our nearest

relations. The evening after our arrival, we were visited by a number of

the British of both sexes. Amongst these was General McLean, Govr of

Lisbon [The General Maclean mentioned by Miss Schaw as "governor of Us.

boo," was Francis Maclean of the Macleans of Blaich, who was a

lieutenant in the army of Cumberland at the siege of Bergen-op-Zoom in

1747, served with Wolfe at Quebec in 1759, and accompanied the

expedition against Belleisle in 1761. His extraordinary position in

Lisbon was due to the fact that when in 1762 France and Spain combined

against Portugal, England offered her assistance and sent Maclean to

organize the military defences of the country. He was appointed in 1762

governor of Almeida and later, as major general, governor of the

province of Estremadura and the city of Lisbon, serving in that capacity

until 1778. On his departure he was presented by Peter III with a sword

and by his consort Maria I with a ring. During the next two years he was

with the army in America as brigadier-general. He died in 1781

(Historical and Genealogical Account of the Clan Maclean, 1838, p.

293).] and commander in chief of the land forces. His name informs you

of his country. He is indeed a fine highland looking fellow, and tho'

not now a boy is still a great favourite with the Ladies. His Aid de

Camp, Major Scott, [The "Major Scott" mentioned here was .John Scott of

Mallony, who in 1742 married Susan, granddaughter of the Marquess of

Tweeddale. Their eldest son, Thomas, served with distinction in America,

Holland, and India.] is from Mid Lothian, Scott of Mollinie's eldest

son, who has been so long abroad, that he has entirely gained the

manners of a foreigner, and tho' a most worthy man and much beloved

here, if ever he returns to his country, Nvill not fail to be called

horribly affected.

But of all the men I have yet seen, I prefer Major Lindsay, ["Major

Lindsay" was probably Major Martin Eccles Lindsay, son of Henry of

Wormiston, though the identification is not certain.] also a Scotchman.

This Gentleman who is universally and justly admired, is brother to

Lindsay of Wormiston in Fife. Never did I see in my life a more

agreeable figure, or more amiable manners than he possesses; he looks

and moves the Gentleman. I am never so happy as when attended by him.

His conversation is elegant, polite and entertaining, his taste is

refined, his remarks judicious. He has such an accurate manner of

explaining the present objects and describing the absent, that I am at a

loss to discover with which of the two I am most pleased. My brother

would doat on him. He is the man entirely to his taste. I am never happy

when he is not with us, and could attend to him the day long. Yet I view

him as a superior being, as he is on the utmost Verge of Mortality, and

in a few weeks at farthest will join his kindred angels. He knows this

is the case and waits his fate with the fortitude of a man and the

resignation of a Christian. It has ever been my lot to pay days of

sorrow for hours of pleasure, and my heart tells me I will sincerely

regret this blasted bud of friendship—indeed the subject already pains

me, so I will say no more.

I ought to have begun my list of civilities

with Sir John Hort, our British consul, as he was the first who waited

on Mr Paisley on our arrival and politely invited us to a ball at his

house the clay following, an offer, which scarcely we knew how to

accept, as we are perfect Goths in the article of dress, so much has

fashion altered since we left Britain. Our friends Mrs Paisley and her

sister Charlotte Pringle however exerted themselves so successfully,

that we really made a decent figure; to me it appeared a most surprising

one, as a French frizier and Portugueze comber exalted my head to a

height I did not believe it capable of attaining, and between flowers,

feathers, and lace, I was perfectly metamorphosed. It did not cost much

to make Miss Rutherfurd fit to appear. At her age every thing does well;

then either the magnificence or simplicity of dress is equally, admired.

Mrs Paisley was always remarkable for the last, and tho' dressed up to

the fashion, still contrives to have it in that style, which is indeed

suitable to her character, which tho' polite to the height of good

breeding, is yet admired for the most gentle and native simplicity that

can adorn the sex in any age or in any station.

The labour of the toilet over, we arrived at

Sir John's, where we found a most superb entertainment for a brilliant

company. To me it appeared particularly so; to me who have not seen any

thing of the kind for so long a time. Here we were presented, or more

properly to speak as a Lady, had presented to us all the foreign Envoys

and residents and one ambassador, but I forget from what court. The

Ladies were all British or French, as no Portugueze Ladies appear in

publick. The King is just now at a palace about 12 or 14 miles off, and

has with him many of the first Nobility. However there were several, and

I thought them genteel- looking people. The house is large and there was

a number of apartments lighted up, which received great Addition from

the manner in which all the fine rooms are furnished here, which is up

to the surbase, where our rooms are painted, with a sort of china-tiles,

as we do the inside of chimneys in England. These are often very fine,

and so nicely fitted as to form complete landscapes. Add to this that

they use the most brilliant cut crystal in Lusters, so that take it

altogether, a Portugueze visiting room is not inferior to the first

drawing room in Europe. We were served in the genteelest style I have

seen. The table was very much on the plan of a West Indian

entertainment, but every thing was hid under the profusion of Artificial

flowers, which cover every thing in this place. Sir John is said to be

very formal in his manners, but to do him justice, I cannot say he

appeared so to me. Mr Paisley says indeed he never saw him so easy as

that Night. Our

Envoy, Mr Walpole, has invited the whole company to his house; but the

day is not fixed. He is a cheerful pleasant man, but tho' he was vastly

polite to our company, I could not help observing he is fond of a

certain species of wit, to which he was too much encouraged by some

Ladies he talked to. This I can easily see is considered as taste, yet

it certainly affords no great triumph, as of all others it is what is

practised by the lower class with greatest success. I know you will tell

me there is a vast difference between vulgar language and a delicate

double entender. But I deny that there can be a delicate method of

treating indelicate subjects, and that all the difference is no more

than Tweedle dee and Tweedle dum. My friend told me on our return, that

I had missed a great deal by not understanding the Portugueze, which it

was her misfortune to do. By the bye I must tell you a very polite piece

of attention in Sir John: finding Mr Neilson did not stay at Mr

Paisley's tho' he saw him there, he waited on him next morning and gave

him his invitation in person.

Such a succession of new scenes presents

itself to me every day, nay every hour, that I am at a loss where to

begin, and seem to want subject, by having too many at my command. All

travellers are fond of ruins, and Lisbon can shew as pretty a set as any

Modern city need boast of. Yet I do not find they afford me such

infinite satisfaction as one might expect. The disagreeable idea that

what has been may be again often intrudes on my Imagination, and I view

churches, Monasteries, palaces and even the Inquisition in ruins with a

sort of reverential awe, and tho' a staunch protestant, cannot help

reflecting on the words of our Saviour, which certainly exclude the

daring insolence of pronouncing what are his Judgments, "Think ye these

on whom the tower of Siloam fell were sinners above all others? I say

nay," These however were not the sentiments of a good Lady, whom I had

the honour to call Grandmother, and who had lived at the period when

miracles and Judgments were greatly the fashion. This affair of Lisbon

gave strength to her doctrine, and tho' she pretended to pity, I really

believe she privately rejoiced at an event that seemed to confirm all

she had said (which was not little) on the subject. She sincerely

believed that this vast Magazine of dreadful materials had been

treasuring up in the bowels of the earth from the foundation of the

world to catch the priests and their votaries at this very nick of time,

when, to use her own words, they had no cloak for their sin. And she

used to ask with a sort of triumph, did any, protestants fall in this, I

trow not. This always finished the whole. For none of her young audience

knew more of the matter than what she told them. Let us not therefore

confine the spirit of persecution alone to popery. This Lady, who wanted

neither sense nor good Nature, was not sorry for any misfortune that

befel a Papist.

I have often been told that Lisbon resembled

Edinburgh. This to me is not very apparent. It is true they are both

built on high ground, but it would require you to bring the Calton bill

into the middle of the city to give a strong resemblance. The houses

built on the hill in Lisbon are finely situated for air, and have one of

the finest prospects in the known world, that of an extensive country,

covered with vineyards, intermixed with churches, Villas, and one of the

King's palaces called Belleim. This luxuriant prospect is at once under

your eye, and joined to it that of a water scene, no less magnificent of

its kind, as the Tagus is here large as a Sea and covered with a vast

number of ships as well as the King's galleys. Every thing appears busy.

I cannot help considering commerce as a chain to link all the human race

to each other, by mutually supplying each other's necessities. I was

much pleased with the prospect I have been describing, but no pleasure

is without its alloy, for I viewed it from the sick chamber of my old

friend Cohn Drummond, brother to your friend the Dutchess of Athole.

[The Duchess of Atholl (second wife of James, 2d Duke of Atholl) was

Jean, daughter of John Drummond of Meginck, Perthshire. Cohn Drummond

was her brother. It is odd that Miss Schaw should speak of her as the "Dutchess

of Athole," because on September 2, 1767, she was married to Lord Adam

Gordon, of the 66th Regiment of Foot, who had just returned from a long

tour through the American colonies (journal printed in Mereness, Travels

in the American Colonies). Her first husband died in 1764. As she had

first married in May, 1749 (Universal Magazine, IV, 239), she must have

been about forty-five in 1775.] He is come to Lisbon as the Denier

resort, and tho' he affects to think himself better, told me privately,

it was all over. This his physician confirmed, adding with some warmth

that the people of Britain loved mightily to be buried at Lisbon, as

they seldom come there, till just ready to step into the grave. [For

many years Englishmen and Scotsmen had made Portugal a British winter

resort. Mr. George writing of the eighteenth century says, "The new

trade in tourists was just beginning with those whose health made a

winter in England a worse hardship than crossing the seas; and

Fielding's account of his journey to Portugal as a luxurious invalid

late in the eighteenth century, shows what hardship then meant. The

moist mild climate of Lisbon was considered suitable for consumptives by

the science of the day, and all who could afford or survive the journey

went with Fielding to fill the British cemetery at Lisbon" (p. 185). The

land for a cemetery was ceded to England in 1655, in accordance with the

XIV article of the treaty of 1654 ("and finally, that a place be

allotted them fit for the burial of their dead"). The most famous

persons who lie buried there are Henry Fielding and Dr. Philip Doddridge,

but scores of others also found in the British cemetery their final

resting place.] I stayed with him all day. He took my visit very kindly,

and his spirits grew much better, while I remained with him. This

however was by no means the case with my own. The unexpected meeting and

the situation he was in very much affected me and recalled to my

remembrance the agreeable circle in which I was accustomed to converse

with him, almost all of whom are now no more.

I was that evening at a very brilliant

assembly given by the factory, [To understand the reference to the

"factory" and the presence of so many English and Scottish merchants in

Lisbon, one must remember that since the treaties of 1642 and 1654, the

marriage treat)' of 1661, which confirmed the earlier arrangements, and

the famous Methuen treaty of 1703, Portuguese commerce had come

practically under British control. British merchants established

themselves in Oporto and Lisbon, receiving and selling imported

merchandise to the Portuguese, either for home consumption or for export

to Brazil, and for this purpose erected buildings which were used as

warehouses and agencies, for the scoring and selling of goods. In a

sense Portugal became in the eighteenth century Great Britain's

commercial vassal, and the Portuguese merchants rarely rose above the

level of shopkeepers and retail traders. It was this condition of

commercial subordination that Pombal wished to alter by restoring trade

to the natives and making them importers and wholesale dealers in

foreign goods. He was unsuccessful in his effort. The terms "factor" and

"factory" were used as the equivalent of "agent" and "agency." Evidently

the buildings served not only as commission houses and places for

storage, but as residences also and centres for entertainment.] and tho'

there were many fine women, my partiality gave it for our own three

friends Mrs Paisley, Charlotte Pringle, and my own Fanny. I found the

men in general of my opinion, and was informed that some of them had

given a strong proof of their preferences, as Miss Charlotte would soon

be Mrs Main, a Gentleman equal in every way to what I formerly said of

Mr Paisley, and in the same line, as well as connected by the strictest

bond of friendship. I hope it is true.

I saw mass performed one day in the great

church of St Rock, where all the nobles of Lisbon were prostrate on the

ground, covered with their vails. The English seldom or never enter the

churches, but particularly avoid them on high festivals. However one of

Mr Paisley's young Gentlemen went with us. For tho' Miss Pringle had

been a considerable time there, she had never been in any of the

churches. I was much disappointed in the highest part of this showy

religion. I had formed to myself a very grand idea of it, but perhaps it

was owing to the particularity of their church, where the great altar is

never displayed, nor used but when a Bishop or a Cardinal performs the

Service. Two priests were immediately sent to take charge of us, and

they made us step without ceremony over the very backs of the people,

who were on the ground almost quite flat on their faces, and by a

private door landed us behind on the great altar, where they let us see

the Service below by drawing up the crimson velvet curtain, and I own

(God forgive me) that viewing it as I then did, it appeared little more

solemn than my friend Senora Maria's cloth-press. But the altar is very

superb, and adorned with the finest Mosaic work I ever saw, which forms

four beautiful pieces of painting. We now repaired to the Wardrobe,

where we saw some gorgeous dresses for the Cardinal. But the fine

Brussels point took Miss Rutherfurd's fancy so much, that I think the

only method to convert her would be to bribe her with a present of the

prettiest shirt. They showed us two altar-pieces of solid silver, but

more to be coveted than admired, as their richness was their only merit.

We had a very elegant rout at the Paisleys in the evening, and are

engaged for every evening for a week.

I had just got this length, when Mr Paisley

came to in- form me that a Gentleman was in the visiting room, who was

just setting out for England. I send this by him, as I will miss no

opportunity. I am an easy correspondent, however as I can expect no

answer. Adieu, I hope to see you before you can receive another, tho' I

will write again by the King George Packet. Adieu.

I was yesterday at Belleim, the winter

palace of the King; tho' they are just now spending their Holy-days at

one further in the country. The house is by no means fine, and did not

the garden and other appurtenances atone for it, it would hardly be

worth the trouble of going to see, but those indeed are well worthy, of

a traveller's Notice. This garden contains within it variety, enough

almost to satisfy, a Sir William Chalmers, and had I not read his

account of what a garden ought to be, I should not venture to express

all I saw under that single appellation, but tho' it is far from being

so extensive as his plan, yet it contains a great deal more than his

three natural notes of earth, air and water, water, earth and air. As

this palace is intended for a winter residence, every thing has been

done to render it agreeable for that season of the year. The walks are

covered with the finest gravel and sheltered from the cold by hedges of

ever-green. They are so contrived as to stretch your power of walking to

a considerable length, every now and then opening into orange-groves and

shrubberies of various winter plants and flowers.

Nor is unanimated Nature all you have to

amuse you. While we were admiring a row of cape jessamine, which even

now is covered with flowers, a huge elephant laid his proboscis over the

wall against which it was planted. I confess I was startled at the

uncommon salutation, tho' I had no reason. This unwieldy novelty, was

very well secured, and on mounting the stair of an adjoining summer

house, we had a full view of him in safety. What a pigmy is man, when

compared to such an animal as this, and yet is vain enough to pretend

dominion over him. A little further on we met a compartment entirely,

the reverse of the last. This is an Aviary which contains five hundred

singing birds, all exquisite in their plumage, tho' I could not hear

their notes. These are a yearly tribute to the queen from the Brazils,

the Madeira, and indeed from all the dominions where they are to be had.

Their apartment is large and well contrived, of an oval form and grated

over the top. It is planted round with orange-trees, Myrtles, and a

variety of evergreens, and in the middle is a piece of water, which

receives a constant supply from the hands of a Hobe placed at the upper

end, and runs off from the bottom, so as to be always fresh, while a

small grate prevents the little gold and silver fishes from being

carried off, and they look very, pretty frisking about in it.

A little further on, we found Indian fowls

of all denominations, some of them very beautiful and others very much

the reverse. It were impossible to name them all, but they are well

represented on the Indian papers we get home. One however I took more

particalar Notice of, as I had often admired her figure on the gold

medal which hung at NIr, Murray of Stormont's breast, [Nov. 7, 1777.

"Died at Edinburgh, Hon. Mrs. Helen Nicholas Murray, daughter of the

deceased David, Viscount of Stormont, aunt of the present Viscount of

Stormont, and sister of the Earl of Mansfield" (Scots Magazine,1777, p.

627).] and which empowered her to keep in decent order those Misses and

Masters, whose heads and heels were equally light. You will guess I mean

the pelican, which is the badge of her authority as Lady directress of

our assembly. Her power both you and I have felt, tho' much oftener her

goodness and even partiality. This tender mother is not however in fact

lovely, tho' of good report. There were several other compartments

filled by the feathered race of different kinds, but it would he tedious

to mention them all. We now entered a field, at the further end of which

was a whole street of small houses, which we found were occupied by

animals of the most noxious natures, such as pole cats, weasels etc. One

in particular was inhabited by rats of Brazil, of a very large size.

They all came peeping thro' their grates, just like so many nuns, and if

they were to confine only such as they think would do mischief to

society, if free, they were in the right. Behind this we found a very

noble menagerie, in the form of a court. Here are lions, leopards,

panthers, bears and wolves. Both the lioness and the panther have

whelps. The last has the most beautiful kittens it is possible to

conceive. I forgot the tiger, which has also a young family. Tho' there

is a number of officers to attend this ferocious court, they are not

kept neat, and the smell is intolerable.

Leaving this, we found ourselves again in

the garden, and presently arrived at another court, which I may venture

to pronounce magni6cent. This was the menage and the royal stables.

These contain above three score of the finest horses in the world. The

absence of my brother on this occasion, converted my pleasure into pain,

as I could not help bitterly regretting his not enjoying this

satisfaction, and the more I was charmed with these lovely animals

myself, the more sincerely I lamented his Missing that, which of all

other sights would have pleased him most. But I hope on some future

occasion it may be in his power. The elegance of these creatures is past

description, and I admired them so long, that I had scarcely time for

the next sight, which is just behind them, and indeed makes part of the

same buildings. This is no less than thirteen Zebras. But as You have

often seen the Queen's ass, I need not describe them, for they are

exactly the same. They have been endeavouring to break them to draw in

the Kings carriage, which would look very pretty, but tho' several

grooms have been maimed and some even killed in the attempt, they are as

untamed as ever, and tho' many of them have been colted in the stables,

and began as early as possible, it has had no effect. They are

infinitely stronger as well as taller than the common breed of asses,

and I should think mules bred from them would both be useful and much

handsomer than those they at present have. Good night, it is very late

and I write by the light of a lamp, as they use no candles in

bed-chambers here.

The King George packet sails to morrow, and I am set down to finish the

last letter to you from the continent. My hopes are now on the wing, and

I trust that goodness which has hitherto protected me, will carry me

safely to the end of my long voyage, and let me find my friends as much

mine as ever. We

were yesterday a considerable way in the country, where the depredations

of the earthquake are very visible; but our principal object was the

fine aqueduct, on which it was able to make no impression. So compact

and firmly are the stones united, and so indissoluble is the composition

with which they are cemented, that tho' many years have passed since the

water first began to flow thro' it, it is not the least impaired. It has

its beginning sixteen miles up the country and comes over many high

mountains in its way to Lisbon. The arches on which it rests are for

that reason very unequal; on the mountains not exceeding three or four

feet, and in the valleys often rising to above two hundred, as I am

informed, for my eye is not exact enough to judge of heights. The

pillars which support these arches are plain, but strike the Imagination

with an idea of the greatest possible strength. The aqueduct seems to be

from forty to fifty feet in breadth, but the water does not take up

above twelve or fifteen feet of it. A walk is raised on each side, and

the roof appears about sixteen feet high. At the distance of every fifty

feet is an opening, which admits the light and the air, but is so

contrived as to exclude rain. These look like little towers on the

outside. I have been particular as to this fine piece of Architecture,

as I do not recollect ever to have read a description of it, nor indeed

of Lisbon by any hand, who has done it justice. Mr Twiss says a great

deal, but his travels seem only a journal of his own bad humours,

prejudices and mistakes, for I believe he would not willingly tell a

falsehood, but I am at a loss to think where he found the dirty scenes

he describes. I have been at no pains to avoid them, yet have met with

no such thing.

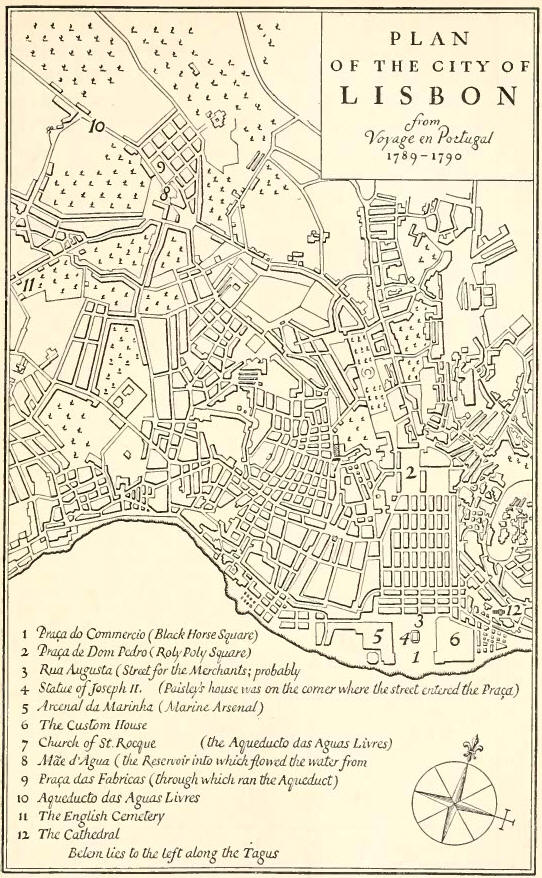

After our return from the country, we took a whole round of the town,

which tho' spacious, I do not like so well as Edinburgh. Their principal

Street (the Rua Augusta) is neither so broad, nor near so long as our

High street, and tho' the people live over head of each other as we do,

the buildings are not so high, nor appear so well built, and the

jalousies on the windows give them all a look of prisons. In this street

is the arsenal, which is a fine building. The town is fast getting the

better of her Misfortunes. Many of the streets are rebuilding in a

handsome and modern manner, and one noble square is finished, in a

corner of which is Mr Paisley's house. Here is a statue of the present

King and the favourite Minister, the Marquis of Ponibal. It is no easy

matter to form an opinion of the character of this statesman, either as

a private man or a minister, one party extolling him, and another

abusing him. He is hated by the princess of BraziI,:: in proportion as

he is loved by her father, and the moment the king dies he will find all

the weight of her resentment. She is said to be very bigoted in matters

of religion, and gloomy and vindictive in her temper. The moderation of

the minister, and the lenity with which he is supposed to have inspired

the king towards hereticks give great offence to her and the clergy,

while the nobility in general are his enemies from his endeavours to

lessen their exorbitant power, and reduce them to the laws of their

country and of humanity. Nor does he gain much approbation from the

middle and low class, who unused to liberty, know not how to make it sit

easy. The severity with which he has punished the crime of murder,

particularly assassination in the streets, has been attended with such

success, that the streets of Lisbon are now as safe as those of any town

in Europe, tho' they are still entirely dark.

I was at a play a few Nights ago and saw an

actress, who had been mistress to a Marquis, whose Jealousy on her

account had made him murder no less than three suspected rivals. For the

last he was banished, and would have been broke on the wheel,

notwithstanding his high rank, had not the princess of Brazil obtained

him the liberty of retiring. The playhouse is not fine, the scenes

paltry and the play unintelligible from the action at least. I wished to

see the Portugueze manner of dressing, and had no other way than this,

as they are ordered to keep strictly to the mode. They have a very good

Italian opera when the court is at Lisbon, but no ladies are admitted.

This they say is owing to the Queen, who is extremely jealous of her

Royal consort, and if we credit report, not without reason. Tho' the

natural character of the men is that of jealousy and suspicion, there is

no place where the women are held in such estimation and treated with

such respect. Every wish is gratified except that of liberty, and even

the husband who confines his cama with bolts and jalousies, never

approaches her, but with the respect and adulation of a passionate

lover. Indeed the violence of his love is his only excuse. I have been

in the parlour of several of the genteelist monasteries, and conversed

with many nuns of the first fashion. They are however very hard of

access, and it requires no small interest to see some of them. They

appeared very much pleased with US, particularly with Fanny, whose

person and manners they highly complimented. They never suffered us to

leave them, without presenting us with some little mark of their

approbation, and we have got as many artificial flowers as would dress a

whole Assembly. I

will have no other opportunity of writing from hence. My next letter

will be from Greenock. Had it not been our care for the boys, we would

have returned by the way of France, and \(r Neilson is perfectly

acquainted with the route. This would have been very agreeable, nor were

we restrained on account of our finances, as Mr Paisley offered us an

unlimited credit to draw on him from every town that was in our route.

Indeed his friendship and attention are not to be described, and I

consider it as no small acquisition to have gained his acquaintance, tho'

my travels had afforded nothing more.

And now, my friend, adieu to our epistolary

correspondence, which I hope ends here, as I sincerely hope we may never

be again as long parted, and that our travels shall mutually serve to

amuse our winter evenings, when we shall travel them over again in the

friendly circle of a cheerful hearth. I have wrote my brother under

cover to Lord T—d, Ld C— B, C—M, and if he is in Britain he will not

fail to get some of them. Be sure to have a letter for me at Greenock,

to the care of your old correspondent George Neil, who is land-waiter

there. Flow many of your letters has he had charge off. Let me know

about my brother. I will positively say Adieu, Adieu. |