|

THE first forty years

of John Knox's life are almost an unbroken blank. His History of the

Reformation in Scotland, which is practically his own biography writ

large, maintains a singular silence regarding the early years of his

career. It is supposed that he was so ashamed "of the time spent in

the puddle of papestry" that he preferred to make no reference to

it. What we know of his birth and parentage, and the influences

which were at work in producing him, can be briefly stated.

He was born in the

year 1505 [See Appendix.] at Gifford Gate, near Haddington. His

father was called William, and he had a brother of the same name.

His mother was a Sinclair. This we know from the fact that,

following the common custom of the time, he used her name as his own

to shelter him from persecution. His earlier biographers connect his

family with the noble House of the Knoxes of Ranfurly in

Renfrew-shire, but there is no ground for this belief. He describes

himself as "a man of base estate and condition," and in an

interesting interview which he had with the Earl of Bothwell the

fact of his humble origin is made perfectly clear. "For albeit that

to this hour it hath not chanced me to speak with your Lordship,

face to face, yet have I borne a good mind to your house. . . . For,

my Lord, my grandfather, goodsher, and father have served your

Lordship's predecessors, and some of them have died under their

standards." It is possible that Knox here refers to the Battle of

Flodden; in any case the interview shows that a feudal relation

existed between the House of Bothwell and his family. Like the other

two supreme Scotsmen, Burns and Carlyle, he sprang from the people.

In mind and heart and character he was a genuine product of the

Scottish soil.

The district of East

Lothian was, long before Knox's day, one of the greenest and most

fertile parts of Scotland. It had little in its physical features to

suggest that hardiness and sternness of character which have been

associated with Knox in popular tradition. But, as those who have

made a deeper study of the life of the great Reformer know, there

was a tenderness in his character which formed no unfitting

counterpart to the scenes of his childhood and youth. The religious

Revolution, in which be

was to play so

distinguished a part, demanded qualities which threw into the

background the sympathy and gentleness which by nature were his. In

his native town Knox would see the Romish Church in all its

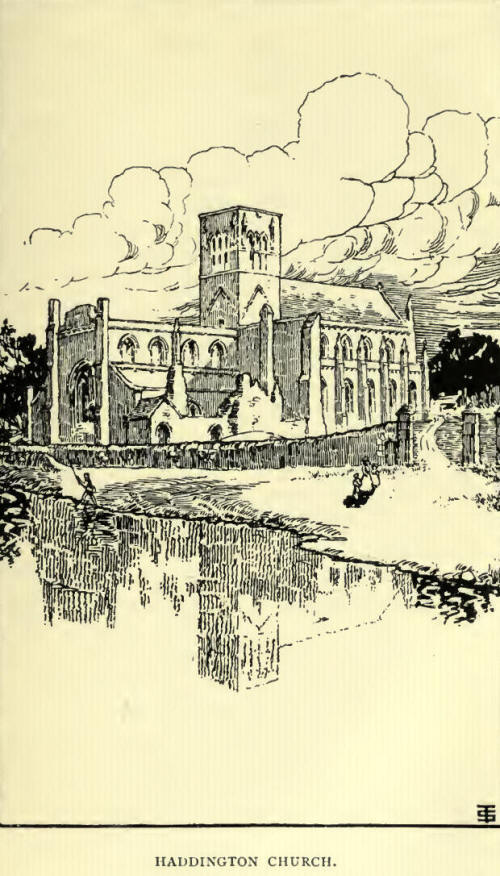

splendour and, at the same time, in all its corruption. Haddington

was rich in monasteries and churches, and one of the latter, from

its beauty of architecture, was called "The Lamp of Lothian."

Whatever his affection for Haddington may have been, he was at no

pains to hide the slowness with which it accepted the new religion.

In the account which he gives of Wishart's preaching there, he

declares that Haddington was fonder of witnessing Clerk Plays than

listening to the Gospel. The wealth and power of the Church in that

district may have accounted for this.

The future Reformer

was educated first in the Burgh School of his native town, and

afterwards in the University of Glasgow. Scotland, even at so early

a date, showed that interest in education which has characterised it

ever since. Knox afterwards, in his Book of Discipline, gave a

sketch of an ideal system of education for his country, but that

system was not his own invention; it had its bedrock in

pre-Reformation times. The burgh schools of Scotland were no

unworthy precursors of the famous grammar schools of a later age.

Knox entered Glasgow

University in 1522, at the age of seventeen years. He would

naturally have gone to the University of St. Andrews, which was

nearer, but the fame of John Major, who had recently been appointed

principal regent or tutor in the College of the Faculty of Arts in

Glasgow, and who was himself a Haddington man, and educated in its

Burgh School, drew Knox to the younger and more distant University

of the West.

John Major would seem

to have been the beau-ideal of the Scottish professor of the time,

but, reading his works in the light of modern thought, it is not

easy to discover the secret of his popularity. Buchanan, who studied

under him afterwards in St. Andrews, is at no pains to conceal his

contempt. He criticises his professor's teaching as "sophistry

rather than dialectics," and the fact that both he and Knox should

have afterwards travelled far in different directions from the

teaching of Major, shows that he had no great influence over them.

Major was a type of the Schoolman who knew something of the new

Learning without being affected by it. He studied in Paris in the

same College as Erasmus, but, unlike the great Humanist, he remained

practically uninfluenced by the spirit of the Renaissance. All the

same, he had imbibed some generous opinions of government and of the

natural rights and liberty of subjects in relation to their rulers.

In this respect he influenced both Buchanan and Knox, and the

latter's manly insistence on his independence and rights to Queen

Mary, "Madam, a subject born within the same," may have been the

full development of the views of his old master.

Glasgow University at

that time gave little or no promise of its great future. It was poor

in endowments and in teaching. The city itself was dominated by the

Church. The Cathedral, with its Archbishop and Prebendaries, was the

centre and source of the life both of the city and the University.

Knox had the benefit of Major's teaching for a year only, for the

latter was transferred in 1523 to the University of St. Andrews, and

he himself is supposed to have left without taking a degree.

Thus far the career

of the Reformer can be partly traced, but for the next twenty years

hardly a single record of it can be found. It is generally believed,

however, that he returned to East Lothian, and acted first as a

notary and afterwards as private tutor in the families of the local

gentry. Indeed, this can be authenticated, for documents have been

recently discovered which prove him to have acted in the former

capacity, and he himself tells us that at the time of Wishart's

preaching in Haddington he was private tutor in the families of

Cockburn of Ormiston and Hugh Douglas of Longniddry. There is no

record of the time when he took priest's Orders, but in later years

his Catholic adversaries railed at him as one of the "Pope's

Knights," and as having received Orders by which he "were umquhile

called Sir John." The tradition, incorporated in his Life by Beza,

and repeated and expanded by later biographers, that he excelled as

a lecturer in Philosophy, and threw over the study of Aristotle for

that of St. Jerome and St. Augustine, may be true, but it is without

historical proof.

Knox, however, must

have been during those long years directing his attention to the

great questions which were influencing the whole of Western Europe.

The minds of men everywhere were being stirred by the religious

Revolution which had already all but run its course on the

Continent, and the fact that Knox suddenly appeared in the Castle of

St. Andrews in 1547 fully armed for the great warfare which he was

to wage, shows that he must have been preparing for it by a long

course of thought and study. He never pretended that there was

anything miraculous in his renunciation of the old religion and his

acceptance of the new. Study and reflection, and external

influences, must be regarded as having played an important part in

that transformation of heart and mind which not only saved himself

but his country from Popish darkness and superstition.

On the Continent, and

even in England, the Renaissance preceded the Reformation; in

Scotland this was reversed. Indeed, the Renaissance never really

took hold in Scottish soil. The Revolution was pre-eminently a

religious one. This may account for its thoroughness, and for the

supreme influence which the Reformed religion exercised over the

life and thought of Scotland for generations. Theology became the

absorbing interest, to the exclusion of Art and Letters. In Germany

and in England it was different. The Renaissance in the former

country preceded the Reformation, and in England they went hand in

hand. This may explain the more human religious life of Luther and

the less intense fervour of the English Reformers. They took a

broader view of life and destiny. Their minds were both Hebraistic

and Hellenistic; while the Scottish mind was Hebraistic only. It is

hard to say whether the Scottish people have gained or lost by this.

For one thing, it has given that moral grit to the nation which has

made it great; while, on the other hand, it has, to a certain

extent, robbed it of those more human interests which play a

necessary part in the all-round development of a people.

But long before the

times of Luther and Calvin a spirit of reform had manifested itself

in the Scottish Church. The Lollards of Kyle in the fifteenth

century preached some of those very doctrines which afterwards

became the watchwords of the Reformation. They had their spiritual

descendants, and from their day until the time of Knox himself, the

blood of Scottish martyrs testified that the spirit of pure religion

was far from dead. The country was thus prepared for a full

participation in the religious Revolution which had already

powerfully affected the Continent, and was making rapid headway in

England. The Reformed views were being spread by means of books and

preachers. The nations that had been under the influence of the

Papacy were beginning; to assert their political rights and to

become individualised. They were attaining to self-consciousness.

The age of unquestioning faith was gone; and Scotland, though a

little in the rear of this movement, was about to show that in

carrying it out it meant to be thorough.

Had the Church in

England, however, not been reformed it is possible that no

religious- Revolution would have taken place in Scotland. The

northern, country at this time was divided in its allegiance between

France and England. Both countries courted its alliance. James v.

was dead. The nation was nominally under the Regency of Arran, but,

as a matter of fact, the real power lay in the hands of Cardinal

Beaton and the Queen-Dowager Mary of Lorraine. 'Those who were bound

by every tie to France saw in an alliance with it the only hope for

the Catholic Church. England, on the other hand, courted the

friendship of Scotland chiefly for political reasons. Henry VIII.,

in order to bind the two countries together, determined to marry his

son, the future King Edward VI., to the young Queen Mary of Scots.

Between Scotland and England there had been a long and deadly

enmity, and the natural tendency of politicians was to favour an

understanding with France; but the secret policy of the latter

country, which was to make of Scotland a French province, caused

them to hesitate, and the Protestant party in the country, which was

now considerable, saw that their only chance of success lay in

friendship with England. Had England remained Roman Catholic the

incipient Protestantism of Scotland would have died a natural death,

for it was the support, partly genuine and partly selfish and

political, which the country across the border gave in the time of

need that really saved Protestantism for Scotland. |