Though small in size,

Kincardineshire has a remarkable muster-roll of notables wiiose

reputation is by no means local.

To begin, it claims to be

the cradle of the family to which Robert Burns belonged. For many

generations Glenbervie had been the home of the family of Burness, as

the name was invariably spelled ; and it was from Clochnahill, near

Stonehaven, that the poet’s father set out to better his fortunes in the

south. It was from his father that Robert Burns inherited his

brain-power, his hypochondria, and his general superiority. Robert’s

cousin, John Burness (1771-1826), was author of Thrummy Cap, which Burns

thought “ the best ghost story in the language.”

Sir Walter Scott’s

connection with the county, though not so close or direct, is

nevertheless interesting. Readers of the Waverley Novels will remember

that it was in the churchyard of Dunnottar that Scott in 1796 first sawr

Robert Paterson, the original of Old Mortality, “engaged in his daily

task of cleaning and repairing the ornaments and epitaphs upon the tomb”

of the Covenanters. Scott, however, became the begetter of one of the

best-known men of the Mearns, the renowned mercenary soldier Captain

Dugald Dalgetty, whose “natural hereditament of Drumthwacket ”was“ the

long waste moor so called, that lies five miles south of Aberdeen,” and

who was naturally an alumnus of Marischal College.

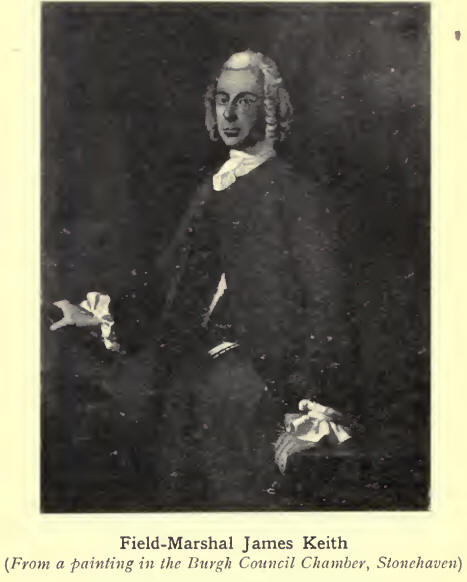

Whether as soldiers,

administrators, courtiers, or patriots, various members of the Keith

family wielded great influence, not only in the county but also

throughout the country, from the eleventh century to 1718, when the last

Earl Marischal’s estates were forfeited to the Crown. This Earl’s

younger brother, James Keith, after military service with the Spaniards

and the Russians, went to Prussia, where Frederick the Great at once

made him field-marshal, and relied greatly on his military genius. In

1758 Keith was killed at Hoch-kirch while for the third time charging

the Austrians.

The Falconers, whose name

came from the Crown office they held, were connected with the county in

the twelfth century. Three of them became senators of the College of

Justice, or Lords of Session. One of these was deprived of his seat,

1649-1660, for “malignancy,” which drew from Drummond of Hawthornden a

sonnet in praise of his character and a lament for his misfortunes.

One would like to head the list of historians with the name of John of

Fordun, author of the important Scoticlnonicon; but that he was bom in

the parish of Fordoun is merely an inference from his name. He

flourished in the fourteenth century. Cosmo Innes (1798-1874), a native

of Durris, was trained as a lawyer. In 1846 he was appointed Professor

of Constitutional Law and History in Edinburgh University. He is best

known for his two historical works—Scotland in the Middle Ages, and

Sketches of Early Scotch History. Dr Cramond, a voluminous writer of

histories dealing chiefly with the north-east of Scotland, belonged to

Fettercairn.

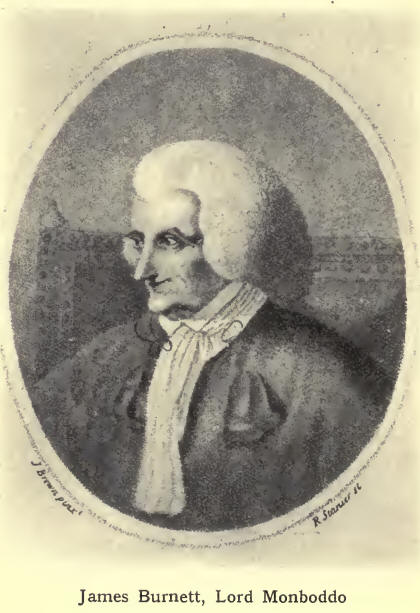

James Burnett (1714-1799), Lord Monboddo, was famous not merely as a

lawyer but also as a litterateur. He first came into prominence as

counsel for the Douglases in the Douglas case, and in 1767 he was made a

Lord of Session, a position he held for thirty years. His Origin and

Progress of Language, in which he anticipated the Darwinian theory, is

very learned and acute, but very eccentric. Lord Neaves, a versatile

successor in the Court of Session, sings of him:

“His views, when forth at first they came,

Appeared a little odd O!

But now we’ve notions much the same,

We’re back to old Monboddo.

“Though Darwin now proclaims the law,

And spreads it far abroad O!

The man that first the secret saw,

Was honest old Monboddo.”

Lord Gardenstone, another

Lord of Session, was like Monboddo, somewhat eccentric, but did much for

the village of Laurencekirk, which he got erected into a Burgh of

Barony. Still another judge was Sir John Wishart, who died in 1576, a

native of Fordoun. He was a comrade of Erskine of Dun in the days of the

Reformation, and fought at Corrichie.

Of ecclesiastical dignitaries the county can show a generous

muster-roll, an outstanding feature being the relatively large number of

bishops. One was Bishop Wishart of St Andrews. Bishop Mitchell, a native

of Garvock, was deprived of his office in 1638, and during his exile in

Holland worked as a clockmaker. Bishop Keith (1681-1757) was born at

Uras, and held the See of Fife. He compiled a valuable history of

Scottish affairs from the beginnings of the Reformation to Mary’s

departure for England in 1568. Gilbert Burnett, Bishop of Salisbury and

friend of William III., was a descendant of the Burnetts of Crathes.

Alexander Arbuthnott (1538-1583), son of Andrew Arbuthnott of Pitcarles,

became Principal of King’s College, Aberdeen, in 1569, and soon after

received the living of Arbuthnott. Dr James Sibbald, who died about

1650, was a Mearns man. He was minister of St Nicholas, Aberdeen, and a

stout opponent of the Covenant. Equally stout on the other side was Rev.

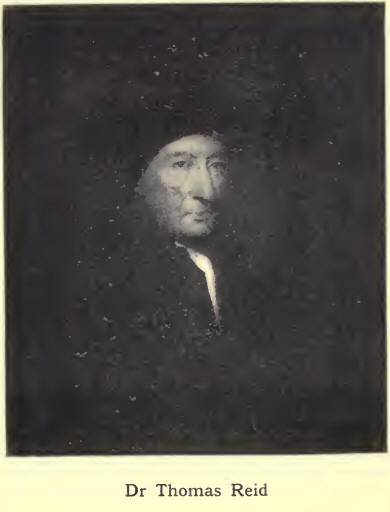

Andrew Cant (1590-1663), a native of Strachan. Another native of

Strachan was Dr Thomas Reid (1710-1796), parish minister of New Machar

in Aberdeenshire and Professor of Philosophy at King’s College,

Aberdeen. He wrote a renowned book— Inquiry into the Human Mind 011 the

Principles of Common Sense—and created the Scottish school of philosophy

opposed to David Hume. He succeeded Adam Smith in Glasgow.

In literature the

greatest name is Dr John Arbuthnot (1667-1735), son of an Episcopalian

clergyman at Arbuthnott. One of the Queen Anne wits and the friend of

Swift and Pope, he wrote the History of John Bull and was the chief

author of the Memoirs of Martinus Scriblerus. “The Doctor,” said Swift,

“has more wit than we all have, and his humanity is equal to his wit.”

Dr James Beattie (1735-1803), a native of Laurencekirk, and schoolmaster

of Fordoun, was appointed to the Chair of Moral Philosophy in Marischal

College, Aberdeen. His Essay on Truth had a great reputation, while his

Spenserian poem The Minstrel still finds readers. George Beattie

(1786-1823), author of John of Arnha, was a native of St Cyrus. Thomas

Ruddiman (16741757), for five years schoolmaster of Laurencekirk, was a

famed Latinist, whose Rudiments had great vogue for many years. David

Herd (1732-1810), who belonged to Marykirk and edited the first

classical collection of Scottish Songs ; Dean Ramsay (1793-1872), author

of Reminiscences of Scottish Life and Character; Dr John Longmuir

(1803-1883), historian of Dunnottar Castle ; and Dr John Brebner

(1833-1902), a native of Fordoun, organiser, and for twenty-five years

head, of the educational system in the Orange Free State, cannot be left

unnamed.

Various members of that

family of strong men, the Barclays of Urie, achieved fame in different

ways. The first was Colonel David Barclay, an old soldier of Gustavus

Adolphus, who purchased Urie. He turned Quaker, and was accordingly

persecuted. Readers of Whittier will remember the poem beginning :

"Up the streets of

Aberdeen,

By the kirk and college-green,

Rode the Laird of Urie.”

Dying in 1686, he was succeeded by his son Robert (1648-1690), who in

1672 had walked in sackcloth through Aberdeen as a protest against the

wickedness of the times. Robert was an eminent man, and his Apology is

the standard exposition of the principles of the Friends. A descendant

of his, who died in 1790, was the famous agriculturist; while another,

Captain Robert Barclay (1779-1854), was a noted pedestrian, whose feat

of walking 1000 miles in 1000 consecutive hours took place at Newmarket

in 1809.

|