The history of the

county, though interesting, has not been much concerned with the great

events of national history. And yet the existence in early days of a

royal residence at Kincardine indicates a certain importance. Kincardine

was probably chosen as a residence by the Pictish kings, because it

commanded the pass of the Mounth and the road to the eastward. Its

castle may have dated from the reign of William the Lyon. In mediaeval

times it was one of the chain of strongholds guarding the route from

Forfarshire over the Mounth to the north—Brechin, Kincardine, Loch

Kinnord, Kildrummy, Strathbogie, Rothes, Elgin, Duffus, Blervie,

Inverness, Dunskaith. As a royal residence, it grew less important when

the midland centres increased in power and influence, and it ceased to

he the capital of the shire in 1600, when Stonehaven became the chief

seat of local administration.

That the Roman legions under Severus (a.d. 208) passed through the

county is undoubted, though the events connected with this invasion are

obscure and disputed. Goaded into revenge by the insurrections of the

wild Caledonians, he set out himself with a strong force, and at once

began the formation or the continuation of the road through the

north-eastern lowlands. The route of the Roman armies through Strathmore

and the Mearns is clearly mapped out in the sites of the camps which run

in a line from Tay to Dee. These were at intervals of about 12 miles, or

a day’s march; and it is reasonable to assume that of the 50,000

soldiers lost by the Emperor in his Caledonian campaign, a certain

proportion must have fallen in the conflict with the sturdy " Men of the

Mearns.” The Roman camps in the county are said to have been at Fordoun,

and Raedykes, near Stonehaven, while Normandykes, in Peterculter, is

just beyond the county border. This view, strongly held by some

authorities, is strongly condemned by others. The battle of the camps

will have to be decided, if that is now possible, by excavations on the

sites. It is noteworthy that, in the Raedykes-Normandykes area, Roman

relics have been unearthed—coins, swords, pots.

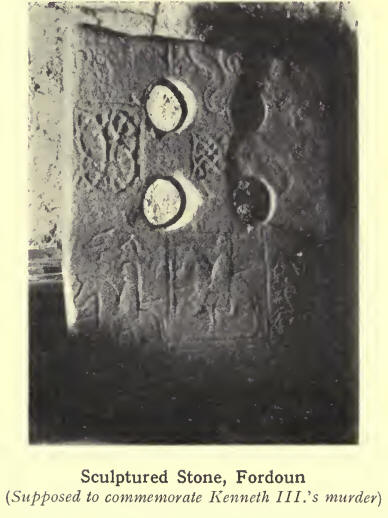

In the wild days when Scotland was in the making, when Piets and Scots,

Angles of Lothian and Britons of Strathclyde, struggled for mastery, the

Mearns on the route from Fife and Perth to Aberdeen and Moray must have

been the scene of many a bloody conflict. After the union of Piets and

Scots, Kenneth MacAlpin’s immediate successors found the Mearns a

constant source of trouble: it was there that three kings died a violent

death. In 954, Malcolm I. was defeated and slain at Fetteresso, though

some say he was killed in Morayland. Forty years later Kenneth III.

incurred the enmity of Finella, wife of the Mormaer of the Mearns, whose

son had died in battle against the king. By her contrivance Kenneth was

killed, but how is not certain. Hector Boece’s account is grimly

picturesque. Kenneth had visited Finella’s castle at Fettercairn and was

conducted into a tower, “ quhilk,” to use the words of

Bellenden’s Scots version of Boece, “was theiket with copper, and hewn

with mani subtle mouldry of sundry flowers and imageries, the work so

curious that it exceeded all the stuff thereof.” There stood a statue of

the king, in his hand a gem-studded apple of gold. The apple (so Kenneth

was told) was a gift for himself. Would he deign to accept it from the

hand of the image? He touched the apple, and at once a shower of arrows

pierced his body. In 1094, when rivals claimed Malcolm Canmore’s throne,

the Mormaer of the Mearns, Malpeder MacLoen, backed Donald Bane against

Duncan II. In a battle at Mondynes in Fordoun parish, Duncan died. A

great stone on a knoll in a field, called Duncan’s Shade, is believed to

commemorate the spot.

In common with the other

parts of the east coast, Kincardineshire suffered from the inroads of

the Danes during the tenth and the early part of the eleventh century.

At the battle' of Barry, their leader, it is said, was killed by the

founder Qf the Keith family, and was buried at Commieston in St Cyrus.

During the period of the Wars of Independence Edward I. passed through

the Mearns on his triumphal march northwards (1296). From Montrose he

directed his course to “ Kincardine in Mearns Manor,” then to Glenbervie

Castle, where he stayed a night, next over the Cairn O’ Mount to “

Durris manor among the mountains.” According to Blind Harry, Wallace

overran the Mearns in the following year, and penned 4000 Englishmen

within Dunnottar.

“Wallace in fyr gert set all haistely,

Brynt \vp the kyrk, and all that was tharin,

Atour the roch the laiff ran with gret dyn.

Sum hang on craggis rycht dulfully to de,

Sum lap, sum fell, sum floteryt in the se.

Na Sotherouu on lyff was lewyt in that hauld,

And thaim within thai brynt in powdir cauld.”

In 1562 the battle of Corrichie was fought on the south-east slope of

the Hill of Fare. Queen Mary was making a progress through the northern

shires when the Earl of Huntly turned rebellious. The royal forces,

under the Earl of Moray, defeated the rebels at Corrichie. From a spot

still named the Queen’s Chair, tradition says Mary viewed the fight.

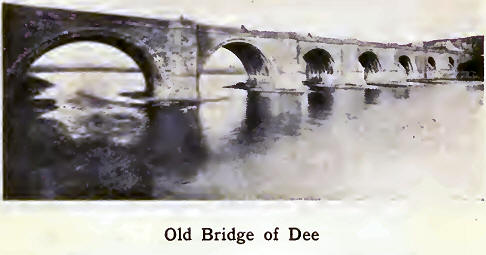

In 1639 the Marquis of

Montrose and his men passed through the county on their way to Aberdeen

to compel the people of Aberdeen to sign the Covenant. The Earl

Marischal and other “Men of the Mearns” joined him. During the

operations round Aberdeen occurred the “Raid of Stanehyve.” Viscount

Ab'oyne crossed the Dee with 2500 men, plundered Muchalls and had

reached Megray Hill, close to Stonehaven, when their opponents met them,

well supplied with cannon from Dunnottar. Highlanders feared “the

musket’s mother,” as they designated the cannon; and those in Aboyne’s

army fled when the cannonade began. Aboyne retired on Aberdeen, blocking

the only approach to the city— the narrow Bridge of Dee—with turf and

stones. The defences were forced and Montrose captured Aberdeen. In

1644, after he had turned Royalist, he was again in the Mearns, marching

from his victory at Tippermuir. Crossing the Dee at Mills of Drum, he

took Aberdeen. A year later he returned and burned the House of Durris.

At Stonehaven he did fearful havoc both by fire and sword, devastating

houses, farms, and woods so that “ the hart, the hind, the deer, and the

roe skirlt at the sicht of the fire,” whatever may have been the

feelings of the sorely stricken inhabitants. Finding that the Earl and

others had secured themselves in Dunnottar Castle, he pillaged and

burned the village of Cowie, with the boats and stores, and all the

lands of Dunnottar, Fetteresso, Glenbervie, and Arbuthnott. Marching

along, he routed a party of the Covenanters at Haulkerton near

Laurencekirk, and made the Howe “black with fire and red with blood.”

His last progress through the Mearns was in 1650, when as a prisoner,

bound hand and foot, he was led to his execution in Edinburgh.

After Charles ll.’s coronation at Scone, January 1, 1651, the “ honours

” of Scotland—the crown, the sword, the sceptre—had been deposited in

Dunnottar. Dunnottar was the last stronghold to yield to Cromwell’s

troops. It was invested in the late autumn of 1651. The English general

knew that the Regalia had been taken into the castle, while George

Ogilvie of Barras, the governor, doubted if he could hold out with his

meagre garrison, especially as food was scanty and mutiny was appearing

among the men. At this crisis Mrs Granger, wife of the minister of

Kinneff, obtained permission to visit Mrs Ogilvy. A scheme was devised

to save the Regalia. When Mrs Granger left, she had the crown concealed

in her lap; and her serving-woman carried the sceptre and the sword in

bundles of flax. A touch of irony is added to the incident in the

tradition that the English general himself gallantly assisted Mrs

Granger to her horse. In a short time the Regalia lay, carefully wrapped

up, under the floor of Kinneff church. There they remained till after

the Restoration.

In 1685, during the scare

of Argyll’s invasion, over a hundred Covenanters from the south-west of

Scotland were imprisoned in Dunnottar. Men and women were shut up in a

vault too small for them either to lie or sit. It had but one window,

and the floor was ankle-deep in mud. After some time, the men and the

women were separated, and several vaults were used instead of one.

From the window of the

large vault twenty-five tried to escape down the steep cliff. Two were

killed ; a few eluded capture ; those who were unsuccessful were bound

and laid on their backs for several hours with burning matches between

their fingers. After two months the survivors were conveyed to Leith,

where they could choose either to take the Test Act or be banished to

the Plantations. Most elected to go into exile.

Like the north-east of

Scotland generally, the north of Kincardineshire was strongly Jacobite,

due to the influence of the Earl Marischal.- In 1715, when, the

Chevalier de St George—the Old Pretender—was passing south from

Peterhead to join his followers, he visited Fetteresso, where he was

proclaimed king. In 1746, when the Duke of Cumberland was marching to

Aberdeen, ultimately to meet the Young Pretender at Culloden, he burned

the Episcopal chapels at Stonehaven, Drumlithie, and Muchalls. The

Episcopal clergy, as favouring the Stewarts, were frequently “rabbled”

at this time, and some of them imprisoned.

|