John Walker, Doctor of Divinity, was born in the

Canongate of Edinburgh. His father—Hector of the grammar school

there—was an excellent classical scholar, and is said to have bestowed

such attention to the education of his son, that when ten years of age

he could read Horner with considerable fluency. At a proper age, he

entered the University, where he studied with merited approbation, and

was iu due course of time licensed to preach by the Presbytery of

Edinburgh.

Dr.

Walker's first presentation was to the parish of Glencorse, about seven

miles to the south of Edinburgh, and which includes part of the Pentland

Hills within its range. Here an excellent opportunity presented itself

to the young clergyman for improvement in his favourite study of

botany—a science to which he had been early attached, and in which he

had already made considerable progress, as well as in other branches of

natural history. In this sequestered and romantic district Dr. Walker

passed some of the pleasantest years of his life. Those hours which he

could spare from his pastoral duties were generally spent in exploring

the green hills of the Pentlands, and in making additions to his

botanical specimens.

Dr.

Walker's first presentation was to the parish of Glencorse, about seven

miles to the south of Edinburgh, and which includes part of the Pentland

Hills within its range. Here an excellent opportunity presented itself

to the young clergyman for improvement in his favourite study of

botany—a science to which he had been early attached, and in which he

had already made considerable progress, as well as in other branches of

natural history. In this sequestered and romantic district Dr. Walker

passed some of the pleasantest years of his life. Those hours which he

could spare from his pastoral duties were generally spent in exploring

the green hills of the Pentlands, and in making additions to his

botanical specimens.

This pleasing pursuit could of course only be

prosecuted during the spring and summer months, but the winter was not

without its amusements. The talents and acquirements of Dr. Walker were

not allowed to remain unnoticed by the more distinguished of his

neighbours and parishioners. Among these were, William Tytler, Esq., of

Woodhouselee, well-known for his historical researches, particularly

into that portion of Scottish history which relates to Mary Queen of

Scots; James Philp, Esq., of Greenlaw, Judge of the High Court of

Admiralty; and Sir James Clerk, Bart., of Pennycuick—a gentleman whose

skill and taste in the fine arts was undisputed; and whose collections

of paintings and memorials of antiquity have rendered the mansion-house

of Pennycuick a place of great interest to the curious. By these

gentlemen the company and conversation of Dr. Walker was greatly

estimated; and a constant intercourse existed between them.

In 1764, the General Assembly, in prosecution of a

benevolent design entered into some years before, respecting the

religious and moral improvement of the Highlands and Islands of

Scotland, appointed Dr. Walker to undertake a mission to these remote

parts of the country. This he readily undertook, and performed his

arduous task to the entire satisfaction of the Assembly. He was also

authorised, by the Commissioners for the Annexed Estates, to inquire

into the natural history and productions—the population—agriculture—and

the fisheries of the Highlands and Hebrides. In prosecution of these

important inquiries, he performed in all six journeys; and, from the

mass of useful information collected, a posthumous work, entitled "An

Economical History of the Hebrides," was published in 1808.

Not long after his first mission to the Highlands,

which tended materially to confirm the high opinion entertained of his

character, Dr. Walker was presented by the Earl of Hopetoun to the

church of Moffat, in the Presytery of Lochmaben, and county of Dumfries.

In this extensive parish a new and inviting field presented itself for

exploring the vegetable kingdom of nature ; and it is probable that the

frequency of his botanising excursions—the utility or propriety of which

were not appreciated by his parishioners—procured for him the title of "the

mad minister of Moffat." There was another prominent trait in the

demeanour of the Doctor, which no doubt had its due weight in

countenancing such an extraordinary soubriquet. This was an

extreme degree of nicety in the arrangement of his dress, especially in

the adjustment of his hair, which it is said occupied the village tonsor

nearly a couple of hours every day.

It is told of the Doctor, that travelling on one

occasion from Moffat to the residence of his friend, Sir James Clerk of

Pennycuick, he stopped at a country barber's on the way to have his hair

dressed. He was personally unknown to Strap, although the latter had

often heard of him. The barber did all in his power to give satisfaction

to his customer; but in vain he curled and uncurled, according to the

Doctor's directions, for nearly three hours. At length, fairly worn out

of patience, he exclaimed—"In all my life, I have never heard of a man

so difficult to please, except' the mad minister of Moffat.' "

This scrupulous attention to his hair he continued to observe until

advancing years compelled him to adopt a wig.

The Doctor himself used to mention that he was one

day walking in a gentleman's park, where he had been collecting insects,

with the handles of an insect net projecting from his pocket. Two ladies

were walking near, and he heard one of them say—"No wonder the Doctor

has his hair so finely frizzled, for he carries his curling tongs with

him."

On the death of Dr. Rarnsay, Professor of Natural

History in the University of Edinburgh, in 1778, Dr. Walker made

application to the Crown for the vacant chair. In this he was

successful, and obtained his commission in 1779. At that period no

direct judgment of the General Assembly stood recorded with respect to

pluralities, but the parishioners of Moffat were alarmed at the

circumstance of their minister's appointment to the Professorship,

justly conceiving that, distant as they were from Edinburgh upwards of

fifty miles, it was impossible he could properly attend to his pastoral

duties. Several meetings of Presbytery were held on the subject, but the

Doctor found ways and means to smooth down the opposition ; and he

continued for some time to hold both appointments. Owing to the

discontent of the people, however, he found his situation extremely

irksome and disagreeable. A few years subsequently he was happily

rescued from his difficulties by the Earl of Lauderdale, who gave him

the church of Colinton, about four miles from Edinburgh; where, from its

proximity to the town, he could more easily fulfil the relative duties

of his appointments.

Dr. Walker may almost be said to have been the

founder of Natural History in the University. His predecessor only

occasionally delivered lectures ; and these were never well encouraged,

owing no doubt to the little interest generally excited at that time on

a subject so important. The want of a proper museum was a radical

defect, which the exertions of Dr. Walker were at length in some measure

able to rectify. His lectures also proved very attractive, not so much

from the eloquence with which they were delivered, as from the vast fund

of facts and general information they comprised. Both in the pulpit and

in lecturing to his classes, the oratory of Dr. Walker was characterised

by a degree of stiffness and formality.

In 1783, when the Royal Society of Edinburgh was

formed, the Professor was one of its earliest and most interested

members. The opposition offered to the incorporation of the Antiquarian

Society, which principally originated in the objections made to the

delivery of a course of lectures on the Philosophy of Natural History by

the late Mr. Smellie, has already been alluded to in our sketch of that

gentleman.

In 1788, Dr. Walker delivered a very excellent course

of lectures in the University on agriculture, which is generally

supposed to have suggested to Sir William Pulteney the idea of founding

a professorship for that important branch of science. In 1792, he

published, for the use of his students, "Institutes of Natural History;

containing Heads of the Lectures on Natural History delivered in the

University of Edinburgh."

Although his talents for literary composition were

considerable, it is not known that the Professor ever appeared before

the public as the author of any separate work of any extent. With the

exception of one or two occasional sermons, and a very curious Treatise

on Mineralogy, his contributions were chiefly limited to the various

learned societies of which he was a member. For the Statistical Account

of Scotland he drew up an account of the parish of Colinton, in a style,

and with a degree of accuracy, which fully proved the peculiar talent he

possessed for topographical and statistical subjects. He intended at one

period to have published a Flora of Scotland, but was anticipated by the

Scottish Flora of Lightfoot, Chaplain to the Duchess of Portland, who

composed his Flora during his travels in Scotland with Pennant.

Dr. Walker's knowledge of plants was not altogether

of a theoretical nature. He made some good experiments on the motion of

the sap in trees, which are published in the Transactions of the

Royal Society of Edinburgh; and in Lord Woodhonselee's Life of

Lord Karnes there are several of the Doctor's letters, which contain

judicious remarks on various points of agriculture aud gardening. There

are still to be seen some vestiges of his attention to the latter, in

the glebe of Moffat, where a few of the less common kinds of trees, such

as pinasters and others, planted by him, are still growing.

The garden of the manse at Colinton, which is

beautifully situated in a small haugh by the river, was carefully laid

off and embellished with a display of indigenous and other hardy plants,

which the Doctor delighted to collect and cultivate. But these botanical

rarities, like other sublunary things, were fleeting, and destined to

take no permanent hold of the soil; for the next incumbent, who was no

amateur of botany, but a good judge of the value of land, turned the

whole into a potato garden!

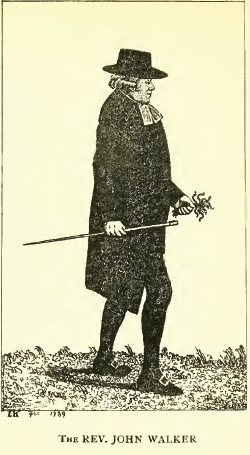

Although the Doctor, in his public appearances, was

somewhat formal and affected, in private life he was extremely social.

He was inclined to society, and had many amusing anecdotes, which he

told with much gaiety and good humour. He was greatly addicted to taking

snuff. Bailie Creech (afterwards Provost), in his convivial hours, was

in the habit of reciting, several of the Professor's stories, at the

same time imitating his manner and peculiarities. He was fond of dress,

as may be inferred from the Etching, where he is drawn with a nosegay in

his hand.

In early life the Doctor was patronised by Lord Bute,

and when in London was presented to Rousseau, to accompany him as

cicerone. They conversed in Latin, the one not being able to speak the

language of the other; and both experienced considerable difficulty in

making themselves intelligible.

Dr. Walker died on the 22nd January, 1804, aged

upwards of seventy. The latter years of his life were rendered painful

by violent inflammation of the eyes, brought on, it is said, by his

habit of sitting very late at his studies, and which ended in loss of

sight. In addition to this calamity, his wife was attacked with a severe

and long illness. She was a sister of Mr. Wauchope of Niddry.

The late Mr. Charles Stewart, University Printer, and

author of an excellent work—"Elements of Natural History," 2 vols.

8vo.—was one of Dr. Walker's executors; and, from his MSS., published

the work already alluded to, under the title of "An Economical History

of the Hebrides and Highlands of Scotland:" Edinburgh, 1808, 2 vols.

8vo. Another volume afterwards appeared, viz., "Essays on Natural

History and Rural Economy : " Edinburgh, 1812, 8vo. Besides many curious

and beautiful manuscripts in his own handwriting, illustrative of the

natural history of Britain, found in his repositories, the Doctor left a

valuable assortment of minerals—a large collection of the insects of

Scotland—and a very extensive herbarium. By his will, it is understood,

he gifted a sum of money for the purposes of Natural History in the

University of Edinburgh.