|

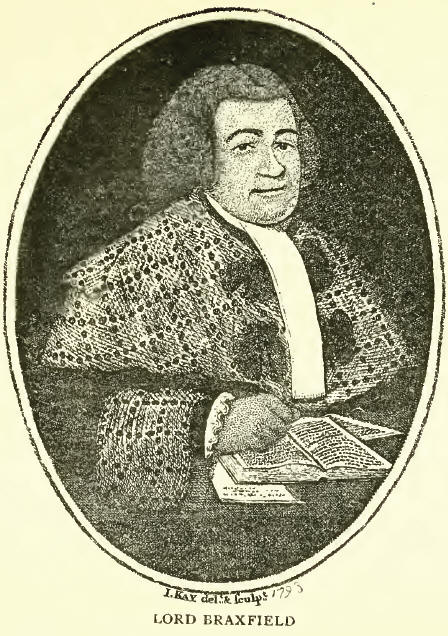

This eminent lawyer and judge of the last century was

born in 1722. His father, John M'Queen, Esq., of Braxfield, in the

county of Lanark, was educated as a lawyer, and practised for some time;

but he gave up business on being appointed Sheriff-Substitute of the

Upper Ward of Lanarkshire. He was by no means wealthy, and, having a

large family, no extravagant views of future advancement seem to have

been entertained respecting his children. Robert, who was his eldest

son, received the early part of his education at the grammar-school of

the county town, and thereafter attended a course at the University of

Edinburgh, with the view of becoming a writer to the signet.

In accordance with this resolution, young M'Queen was apprenticed to Mr.

Thomas Gouldie, an eminent practitioner, and, during the latter period

of his service, he had an opportunity of superintending the management

of processes before the Supreme Court. Those faculties of mind which

subsequently distinguished him both as a lawyer and a judge, were thus

called into active operation; and feeling conscious of intellectual

strength, he resolved to try his fortune at the bar. This new-kindled

ambition by no means disturbed his arrangement with Mr. Gouldie, with

whom he continued until the expiry of his indenture. In the meantime,

however, he set about the study of the civil and feudal law, and very

soon became deeply conversant in the principles of both, especially of

the latter.

In 1744, after the usual trials, he became a member of the Faculty of

Advocates. In the course of a few years afterwards, a number of

questions arising out of the Rebellion in 1745, respecting the forfeited

estates, came to be decided, in all of which M'Queen had the good

fortune to be appointed counsel for the crown. Nothing could be more

opportunely favourable for demonstrating the young advocate's talent*

than this fortuitous circumstance. The extent of knowledge which he

displayed as a feudal lawyer, in the management of these cases—some of

them of the greatest importance—obtained for him a degree of reputation

which soon became for him substantially apparent in the rapid increase

of his general practice. The easy unaffected manners of Mr. M'Queen also

tended much to promote success. At those meetings called consultations,

which, for many years after his admission to the bar, were generally

held in taverns, he "peculiarly shone," both in legal and social

qualifications. Ultimately his practice became so great, especially

before the Lord Ordinary, that he has been repeatedly known to plead

from fifteen to twenty causes in one day. Some idea of the influence and

high character to which he had attained as an advocate, may be gathered

from the couplet in the "Court of Session Garland," by Boswell:—

"However of our cause not being ashamed,

Unto the whole Lords we

straightway reclaimed;

And our petition was appointed to be seen,

Because it was drawn by Robbie Macqueen."

On the

death of Lord Coalston, in 1766, Mr. M'Queen was elevated to the bench

by the title of Lord Braxfield—an appointment, it is said, he accepted

with considerable reluctance, being in receipt of a much larger

professional income. He was prevailed upon, however, to accept the gown

by the repeated entreaties of Lord President Dundas, and the Lord

Advocate, afterwards Lord Melville. In 1780, he was appointed a Lord

Commissioner of Justiciary; and, in 1787, was still more highly honoured

by being promoted to the important office of Lard Justice-Clerk of

Scotland. "Mr. M'Queen had contracted an intimacy with Mr. Dundas,

afterwards Lord President of the Court of Session, and his brother, Lord

Melville, at a very early period of life. The Lord President, when at

the bar, married the heiress of Bonning-ton, an estate, situated within

a mile of Braxfield. During the recesses of the Court, these eminent men

used to meet at their country seats, and read and study law together.

This intimacy, so honourable and advantageous to both, continued through

life."

Lord Braxfield was equally distinguished on the

bench as lie had been at the bar. He attended to his duties with the

utmost regularity, daily making his appearance in court, even during

winter, by nine o'clock in the morning; and it seemed in him a prominent

and honourable principle of action to mitigate the evils of the "law's

delay," by a despatch of decision, which will appear the more

extraordinary considering the number of causes brought before him while

he sat as Judge Ordinary of the Outer House.

As Lord

Justice-Clerk, he presided at the trials of Muir, Palmer, Skirving,

Margarot, Gerrald, etc., in 1793-4. At a period so critical and so

alarming to all settled governments, the situation of Lord Justice-Clerk

was one of peculiar responsibility, and indeed of such a nature as to

preclude the possibility of giving entire satisfaction. During this

eventful period Lord Braxfield discharged what he conceived to be his

duty with firmness, and in accordance to the letter and spirit of the

law, if not always with that leniency and moderation which in the

present day would have been esteemed essential.

The

conduct of Lord Braxfield, during these memorable trials, has indeed

been freely censured in recent times as having been distinguished by

great and unnecessary severity ; but the truth is, he was extremely well

fitted for the crises in which he was called on to perform so

conspicuous a part; for, by the bold and fearless front he assumed, at a

time when almost every other person in authority quailed beneath the

gathering storm, he contributed not a little to curb the lawless spirit

that was abroad, and which threatened a repetition of that reign of

terror and anarchy which so fearfully devastated a neighbouring country.

But if the conduct of his lordship in those trying times was thus

distinguished by high moral courage, that of the prisoners implicated in

these transactions, it cannot be denied, was marked by equal firmness.

During the trial of Skirving, this person conceiving Braxfield was

endeavouring by his gestures to intimidate him, boldly addressed him

thus: "It is altogether unavailing for your lordship to menace me; for I

have long learned to fear not the face of man."

As an

instance of his great nerve, it may be mentioned that Lord Braxfield,

after the trials were over, which was generally about midnight, always

walked home to his house in George Square alone and unprotected. He was

in the habit, too, of speaking his mind on the conduct of the Eadicals

of those clays in the most open and fearless manner, when almost every

other person was afraid to open their lips, and used frequently to say,

in his own blunt manner, "They would a' be muckle the better o' being

hanged!"

When his lordship paid his addresses to his

second wife, the courtship was carried on in the following

characteristic manner. Instead of going about the bush, his lordship,

without any preliminary overtures, deliberately called upon the lady,

"and popped the question" in words to this effect:—"Lizzy, I am looking

out for a wife, and I thought you just the person that would suit me.

Let me have your answer, aff or on, the morn, and nae mair about it! "

The lady, who understood his humour, returned a favourable answer next

day, and the marriage was solemnized without loss of time.

Lord Braxfield was a person of robust frame—of a warm or rather hasty

temper—and, to "ears polite," might not have been considered very

courteous in his manner. "Notwithstanding, he possessed a benevolence of

heart," says a contemporary, "which made him highly susceptible of

friendship, and the company was always lively and happy of which he was

a member."

His lordship was among the last of our

judges who rigidly adhered to the broad Scotch dialect. "Hae ye ony

counsel, man?" said he to Maurice Margarot, when placed at the bar.

"No." "Do you want to hae ony appointit'?" continued the judge. "No,"

replied Margarot, "I only want an interpreter to make me understand what

your lordship says!"

Of Lord Braxfield and his

contemporaries there are innumerable anecdotes. When that well-known

bacchanalian, Lord Newton, was an advocate, he happened one morning to

be pleading before Braxfield, after a night of hard drinking. It so

occurred that the opposing counsel, although a more refined devotee of

the jolly god, was in no better condition. Lord Braxfield observing how

matters stood on both sides of the question, addressed the counsel in

his usual unceremonious manner—"Gentlemen," said he, "ye may just pack

up your papers and gang hame; the tane o' ye's rifting punch, and the

ither's belching claret—and there'll be nae gude got out o' ye the day!"

Being one day at an entertainment given by Lord Douglas to a few of his

neighbours in the old Castle of Douglas, port was the only description

of wine produced after dinner. The Lord Justice-Clerk, with his usual

frankness, demanded of his host if " there was nae claret in the

Castle?" "I believe there is," said Lord Douglas, "but my butler tells

me it is not good." "Let's pree't," said Braxfield, in his favourite

dialect. A bottle of the claret having been instantly produced and

circulated, all present were unanimous in pronouncing it excellent. "I

propose," said the facetious old judge, addressing himself to Dr.

M'Cubbin, the parish clergyman, who was present, "as fama elamosa has

gone forth against this wine, that yon absolve it." "I know," replied

the Doctor, at once perceiving the allusion to Church-court phraseology,

"that you are a very good judge in cases of civil and criminal law; but

I see you do not understand the laws of the Church. "We never absolve

till after three several appearances!''' Nobody could relish better than

Lord Braxfield the wit or the condition of absolution.

After a laborious and very useful life, Lord Braxfield died on the 30th

of May, 1799, in the 78th year of his age. He was twice married. By his

first lady, Miss Mary Agnew, niece of the late Sir Andrew Agnew, he had

two sons and two daughters. By his second lady, Miss Elizabeth Ord,

daughter of the late Lord Chief Baron Ord, he had no children.

His eldest son, Robert Dundas M'Queen, inherited the estate of Braxfield,

and married Lady Lilias Montgomery, daughter of the late Earl of

Eglintoun. The second entered the army, and was latterly a Captain in

the 18th regiment of foot. The eldest daughter, Mary, was married to

William Honeyman, Esq. of Graemsay, afterwards elevated to the bench by

the title of Lord Annandale, and created a Baronet in 1804. The second,

Catherine, was married to John Macdonald, Esq. of Clanronald. |