|

ON the 3rd of December, 1778, the Duchesse de

Chartres presented Paul Jones's letter to the King; on the 17th he was

summoned to Versailles and granted an audience lasting an hour; the

details of which, according to etiquette, never transpired, even in the

private papers found after his death. The following month de Sartine was

commanded to place a ship, equal in tonnage and armament to the Indien,

at his orders. There is unintentional humour in de Sartine's letter,

which commences:- "In consequence

of the exposition which I have laid before the King of the distinguished

manner in which you have served the United States . . . the King has

thought proper to place under your command the ship Buras, of forty

guns, at present at l'Orient," the writer lavishly promises everything

in his power "to promote the success of your enterprise," all of which

Jones, after his experiences, must have taken with a very large grain of

salt.

Captain Jones was to sail under the flag

of the United States, "to form his equipage of American subjects,"

though, as there might be some difficulty in this, the King allowed him

to levy volunteers as he saw fit, "exclusive of those who are necessary

to manoeuvre the ship." He was to cruise in European or American waters

at his discretion, but to render account of his actions as often as he

entered "the ports under the dominion of the King."

This letter would have easily convinced

any one not behind the scenes that it was to the incessant and untiring

efforts of M. de Sartine that Paul Jones owed his long-deferred command,

and the concluding paragraph does not lessen the effect. Possibly, like

many of those who distribute the favours of others, de Sartine really

believed what he wrote.

"So flattering a mark of the confidence

with which you are honoured cannot but encourage you to use all your

zeal in the common cause, persuaded as I am that you will justify my

opinion on every occasion. It only rests with me to recommend to you to

show those prisoners who may fall into your hands those sentiments of

humanity which the King professes towards his enemies, and to take the

greatest care not only of your own equipage, but also of all the ships

which may be placed under your orders."

Paul affected to believe all these

rhetorically impressive sentiments, and wrote, thanking de Sartine as

cordially as if certain contretemps had never been. He expressed his

obligation to the minister for allowing the name of the Dras to be

changed to Le Bonhomme Richard, "as it gives me a pleasing opportunity

of paying a well merited compliment to a great and good man, to whom I

am under obligations, and who honours me with his friendship.

"With the rays of hope once more lighting

up the prospect, my first dez'oir was at the Palais Royale, to thank the

more than royal—the divine—woman to whose grace I felt I owed all. She

received me with her customary calmness. To my perhaps impassioned

sentiments of gratitude she responded with serene composure, that if she

had been instrumental in bringing the affair to a successful issue, it

was no more than her duty to a man who, as she believed, sought only

opportunity to serve the common cause, now equally as dear to France as

to America, and that she was sure I would make the best of the

opportunity that had been brought about."

Paul was overwhelmed by the graciousness

of the Princess, and with his intensely chivalric and beauty- loving

nature and the romance which formed so strong an element in his complex

personality, burned to distinguish himself in the eyes of a woman who

believed him capable of great deeds. Had he lived a few hundreds of

years before, this romantic strain would have found outlet in scouring

arid deserts for an oasis, at which grew fruits on an unclimbable tree,

to lay at the feet of an exigeante lady-love as a gage d'amour. As it

was, he swore to "lay an English frigate at her feet"—and kept his word.

The interview was a long one, and, he

tells us, "she said there was a more serious concern that had come to

her knowledge; that she knew I was not at the moment suitably provided

with private resources, and that in consequence she had directed her

banker to place to my credit at the house of his correspondent in

l'Orient, M. Gourlade, a certain sum, the notice of which I would find

awaiting me on my arrival. She enjoined upon me to offer neither thanks

nor protestations to her on account of it." She waved aside the

attempted explanations, that Le Ray de Chaumont had made some provision

for expenses, and "quite impatiently retorted that M. de Chaumont's

arrangements were not her affair, and commanded me to be silent on the

subject. Then she dismissed me with a 'ban voyage, ne noubliez pas,' and

a pleasant reminder that 1 had long ago promised, if fortune should

smile upon me, 'to lay an English frigate at her feet!' whereupon I took

my leave, and at once set out for l'Orient."

Thanks to the Duchesse's munificent gift

of ten thousand louis d'or, with its purchasing power of three times the

sum to-day, Jones was relieved of that harassing bate noii, lack of

funds, and able to fit out the Bonhomme Richard without delay. He

considered the money as a loan, but when he spoke to the Due d'Orléans

in 1786 about repaying it, the latter replied positively, "Not unless

you wish her to dismiss you from her esteem and banish you from her

salon! She did not lend it to you; she gave it to the cause."

Le Duc de Duras, now Jones's ship, under

the name of the Bonhomme Richard, was built in 1766 for the French East

India Company, from whom the King had just purchased her to be used as

an armed transport. Twelve years' hard voyaging to the East Indies had

reduced her to a state of very great dilapidation, and a thorough

overhauling was imperative, which took from February till June, though

he "exhausted every endeavour to hurry them, and was treated very fairly

by the French dockyard authorities."

Jones had many changes to make in the

Bonhomme Richard, which, though a reliable ship for passengers and

cargo, where steady sailing was all required, was in truth an unwieldy

old craft. He describes her as "sailing well with the wind abaft her

beam," when close hauled she "pointed up badly, steered hard and

unsteady, and made much leeway. She would not hold her luff five minutes

with the weather-leech shivering in the fore-topsail, and had to be

either eased off or broached to quickly or she would fall off aback, if

not closely conned. I mention this because the ability of a ship to hold

her luff, if necessary, right up into the teeth of the wind, and even

after that to hold steering way enough to wear or tack as occasion may

require, is frequently of supreme importance in battle, and,1all other

things being equal, has decided the fate of many ship-to-ship combats at

sea."

The re-christened Bonhomme Richard was

152 feet over all, with a tonnage of 998 tons (French). She carried,

when turned over to Paul Jones, fourteen long twelve-pounders, and

fourteen long nines, and twelve six-pounders. "Her main or gun deck was

roomy, and of good height under beams. . . . Below the main deck aft was

a large steerage, or, as it would be called in a man-of-war, a

'gun-room,' extending some distance forward of the step of the

mizzen-mast. This deck had been used for passengers when the ship was an

Indiaman; but as the port sills of it were a good four feet above water

when the ship was at her deep trim, I determined to make a partial lower

gun-deck of it by cutting six ports on a side and mounting in them

twelve eighteen-pounders. But, being able to obtain only eight

eighteens, I cut only four ports on a side, and in fact put to sea with

only six eighteen-pounders, two of the eight being unfit for service

when turned over to me."

He goes into a wealth of technical detail

as to his changes in the Bonhornme Richard, but sums up that:

This made her, with the eighteen-pounders,

a fair equivalent of a thirty-six-gun frigate; or without them, the

equal of the thirty-two as usually rated in the regular rate-list of the

English and French navies." A crew of three hundred and seventy-five all

told was enlisted. The Americans, including officers, only counted

fifty. A "hundred and ninety odd were aliens, partly enlisted from

British prisoners of war, partly Portuguese, a few French sailors or

fishermen, and some Lascars. In addition to these two hundred and forty

seamen I shipped one hundred and twenty- two French soldiers, who were

allowed to volunteer from the garrison, few or none of whom had before

served aboard ship, and the commandant of the dockyard loaned me twelve

regular marines, whom I made non-commissioned officers. The regular

marine guard for a ship of the Richard's size or rate would be about

fifty to sixty of all ranks. My reason for shipping such a large number

was that I meditated descents on the enemy's coasts, and also that I

wished to be sure of force enough to keep my mixed and motley crew of

seamen in order." The rest of the squadron were the Alliance, Pallas and

Vengeance, and a coastguard cutter called the Ccr/. It was arranged that

Lafayette, with seven hundred men, was to join the expediton. He writes

enthusiastically to Paul Jones that we most not, if possible, put troops

on hoard of her (the Alliance), because there would he disputes between

the land officers and Capt. Landais. Don't you think, my dear sir, that

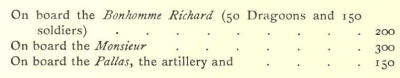

we might have them divided in this way-

"If you don't like it, you might have 150

men on hoard of the Alliance, but I fear disputes. M. de Chaumont will

make the little arrangements for the table of the officers, etc."

Lafayette was admittedly a poseur, and

his concluding paragraph, quoted below, is an example of the strange

composition of this man's nature; who could lay such stress on trivial

details, and unconcernedly impoverish himself and his family with a

quixotism unsurpassed by the Knight of la Mancha himself.

"Though the command is not equal to my

military rank, the love of the public cause made me very happy to take

it; and as this motive is the only one which conducts all my private and

public actions, I am sure I'll find in you the same zeal, and we shall

do as much and more than any others would perform in the same situation,

Be certain, my dear Sir, that I'll be happy to divide with you whatever

share of glory may await us, and that my esteem and affection for you is

truly felt, and will last for ever."

But Lafayette's family had no wish to see

him go to sea in company with so determined a fighter as his Scotch

friend, and he wrote on May 22nd, 1779, "I dare say you will be sorry to

hear that the King's dispositions concerning our plans have been quite

altered, and that instead of meeting you I am now going to take command

of the King's regiment at Saintes." The Court was at this moment

planning one of those colossal spectacular invasions of England, which,

though they never matured, proved a favourite and more than

semi-occasional project, causing less harm to the island neighbours than

the modest attempts of Paul Jones and his forays on the Scotch coast.

The squadron of which Jones supposed he

was to have chief command comprised the Bonhomine Richard, the Alliance,

the Pallas, the Vengeance brig, and the Ce7/, a fine cutter. Jones had,

with his usual daring, planned nothing less than an attack on Liverpool.

"A plan," he says, "was laid, which promised perfect success, and, had

it succeeded, would have astonished the world." No less than five

hundred picked men from the famous Irish brigade, under command of Mr.

Fitzmaurice, were to have taken part in the attempt. But, unfortunately,

"a person (de Chaumont) was appointed commissary, and unwisely intrusted

with the secret of the expedition. The commissary took upon himself the

whole direction at l'Orient; but the secret was too big for him to keep.

All Paris rang with the expedition from l'Orient; and government was

obliged to drop the plan when the squadron lay ready for sea, and the

troops ready to embark."

In an evil hour he solicited that the

Alliance, a new American frigate, of which the command had been given by

Congress to one Landais, a Frenchman, should be added to his force. As

Dr. Franklin had just been formally appointed ambassador to the Court of

France, Jones imagined that not only the disposal of the frigate, but

the power of displacing its commander at pleasure, was vested in him, as

guardian of American interests in Europe."

This, presumably, could not be done, and

he had the vexation of seeing the fastest sailing ship in his squadron

commanded by a man whose enmity towards him was constant and undying.

Pierre Landais, a disgraced officer in the French service, cashiered for

insubordination and refusal to pay debts of honour; disowned by his

family and without career, had been glad to engage as captain of one of

the ships sent by Beaumarchais to America with supplies for Washington's

army. He was a plausible scoundrel, and once in America, represented

himself as a French naval officer on leave for the purpose of giving his

services to the new navy, and the Congress, without looking into the

matter, and thinking to please their French allies, precipitately gave

him command of the best ship they had, and fate decreed that he should

be a perpetual thorn in Paul Jones's flesh.

On June 10th, 1779, "M. de Chaumont

presents his compliments to Mr. Jones, and informs him that everything

is on board except the powder, which will require only two hours, when

he may set sail with a favourable wind.

"M. de Chaumont informs, at the same

time, Mr. Jones that he will have papers to sign before his departure,

for the sundry articles which the King has furnished the ship; therefore

M. de Chaumont earnestly entreats Mr. Jones not to neglect it,

considering the immense expense which the vessels in the port have

occasioned to the King." Jones is reminded that "M. de Sartinc has left

to him and to M. Landais the choice of two excellent American pilots,

and his attention is called to the situation of the (French) officers

who have accepted commissions from Congress to join the armament of the

Bonhomme Richard which you command, may be in contradiction with the

interests of their own ships; this induces me to request you to enter

into an engagement with me that you shall not require from the said

vessels any services but such as will be conformable with the orders

which those officers shall have, and that in no case shall you require

any change to be made in the formation of their crews, which, as well as

the vessels themselves and their armament, shall he entirely at the

disposition of the commandants of the said vessel." This stipulation was

one of the first straws to show which way the wind blew, and the

precursor of that unheard-of "Concordat" which Jones was obliged to sign

before putting to sea with his squadron the second time.

Paul's few leisure moments were filled

listening to the miscellaneous advice with which every one gratuitously

inundated him, and which varied in text from de Chaumont's lamentations

over the King's outlay, to Dr. Franklin's perpetual reiterations that

Jones should play the game of war in a genteel and harmless fashion

where the enemy was concerned, sparing everything and everybody sparable,

and treat his prisoners "with kindness and consideration."

If Franklin really objected to war and

its inevitable boisterousness, why did he abandon all his occupations,

go to France, and work indefatigably to get French help for the

Americans, when he knew that such help would embroil several unoffending

nations into the war he so deplored? Dr. Franklin is not consistent, and

belongs to that great army of temporisers of which the American

revolution is so full; who made little effort to back up their

representatives, and classed this non-support under the heading of

"diplomatic relations." The philosophical doctor was not wholly lacking

an eye to the main chance, and there is a suggestiveness in the

postscript of one of these letters—" N.B.—If it should fall in your way,

remember that the Hudson's Bay ships are very valuable. B. F."

As the attack on Liverpool had been

abandoned, thanks to that "tattling commissary," as Jones aptly calls de

Chaumont, and there were, for the moment, no definite plans for a

cruise, the squadron put to sea with a convoy of merchant ships and

transports with troops, etc., bound to the different ports and garrisons

between this place and Bordeaux."

The American squadron consisted of the

Banhomme Richard, 42 guns, Alliance, 36 guns, Pallas 30 guns, Cerf, 18

guns, and the Vengeance, 12 guns, and sailed from l'Orient on June 19th,

On June 14, 1779, Le Ray de Chaumont

produced a paper called a "Concordat" for the five captains to sign. No

historian has been able to assign suitable reasons for such a

proceeding, which forced the commander, by his own signature, to deprive

himself of all benefits of superior rank, and agree to do nothing

without consulting the other captains, who, instead of being subordinate

officers under his command, became "colleagues," on a practical equality

with their commander, the effect of which "was to destroy all discipline

in the squadron."

Commodore Jones was furious, and demanded

of Chaumont, "What could have inspired you with such sentiments of

distrust towards me, after the ocular proofs of hospitality which I so

long experienced in your house, and after the warm expressions of

generous and unbounded friendship which I had so constantly been

honoured with in your letters, exceeds my mental faculties to

comprehend. . . . I cannot think you are personally my enemy. I rather

imagine that your conduct towards me at l'Orient has arisen from the

base misrepresentation of some secret villainy."

To Mr. Hewes he freely expresses his

feelings about the "most amazing document that the putative commander of

a naval force in time of war was ever forced to sign on the eve of

weighing anchor."

"I am tolerably familiar with the history

of naval operations from the remotest time of classical antiquity to the

present day; but I have not heard or read of anything like this. I am

sure that when Themistocles took command of the Grecian fleet, he was

not compelled to sign such a 'Concordat'; nor can I find anything to

exhibit that Lord Hawke in the French war, nor any English or French

flag officer in this war had been subjected to such voluntary

renouncement of proper authority.

"These being the two extremes of ancient

and of modern naval history without a precedent, I think I am entitled

to consider myself the subject of a complete innovation; or, in other

words, the victim of an entirely novel plan of naval regulations.

". . . It is my custom to live lip to the

terms of papers that I sign. I am at this writing unable to see that, by

signing this paper, I have done less than surrender all military right

of seniority, or that I have any real right to consider my flagship

anything more than a convenient rendezvous where the captains of the

other ships may assemble whenever it please them to do so, for the

purpose of talking things over, and agreeing—if they can agree—upon a

course of sailing or a plan of operations from time to time.

"Yet, strange and absurd as all this may

appear, I was constrained to sign this infernal paper by a word from Dr.

Franklin, which, though veiled under the guise of 'advice,' came to me

with all the force of an order.

"You know that not only is the word of

Dr. Franklin law to me, but also his expression or even intimation of a

wish is received by me as a command to be obeyed instantly without

inquiry or debate the doctor himself knows this.

"I am so sure that the doctor always does

the best he can, that I never annoy him with inquiries. I can at least

see my way clear to some sort of a cruise. I hope to realise in it some

of my ambition towards promoting the reputation of the United States on

the sea."

Jones then alludes to the moral effect

which the capture of the Drake had "on the continent of Europe, and

alarmed the English more than they have been alarmed in many years, if

ever. It taught the English, and proved to the rest of the world, that a

regular British man-of-war, fully manned, well handled and ably

commanded, could be reduced in one hour, by a slightly inferior ship, to

total wreck and helplessness, and forced to surrender in order to save

the lives of the remnant of her crew in sight of their own coast; and

all this, not by desperate boarding, but by simple straightway

broadsiding at close range, the whole battle being fought on one tack

and without manoeuvre.

But now, with the force I have,

ill-assorted as it is, and hampered as it may be by the untoward

conditions I have already confided to you, I can, if fortune favours me,

fight a much more impressive battle.

"I might have a better ship, and my crew

would be better if they were all Americans. But I am truly grateful for

ship and crew as they are; and, if I should fail and fall, I wish this

writing to witness that I take all the blame upon myself."

Hewes was a dying man when he received

this letter, which was found among his papers, endorsed "It is to be

seen that he considers himself now at the end of his resources, and that

he must do or die with the weapons in his hands. I only hope that life

may be spared me long enough to know the ending. I am sure, from what he

says at the end of his letter, that he will either gain a memorable

success, or, if overmatched, go down with his flag flying and his guns

firing. To me, who know him better than any one else does, his words,

'if I should fail and fall' mean that he intends both shall be if one

is; that, if this must fail, he is resolved to fall; that he will not

survive defeat. Knowing him as I do, the desperate resolution

fore-shadowed in his words fills me in my present weak state with the

gloomiest feelings." Life was not spared this staunch friend, who died

ere news of the fight between the Serapis and the Bonhomme Richard had

crossed the wide expanse of ocean.

Franklin had sent Commodore Jones secret

orders as to the plans to be observed on the cruise; and Jones

complains, with much reason, of having seen a letter from the "tattling

commissary" to a junior officer under his command, in which the "secret

orders" were freely discussed! What could a commander do when his fleet,

to the cabin boys, knew his private affairs a little better than he

himself did?

In John Kilby's narrative is the funnily

worded item "The first thing that happened as we were beating down to

the Island of Groix: a man fell off the main-topsail yard on the

quarter-deck. As he fell he struck the cock of Jones's hat, but did no

injury to Jones. He was killed, and buried on the Island of Groix

"—which gives a certain vague and delightfully piratical tinge to the

commencement of the cruise!

The squadron having sailed on June 19th,

the evening of the following day the Commander had " the satisfaction to

see the latter part of the convoy safe within the entrance of the river

of Bordeaux. But at midnight, while lying-to off the Isle of Yew, the

Bonhomme Richard and Alliance got foul of one another, and carried away

the head and cutwater, spritsail yard and jibboom of the former, with

the mizzen-mast of the latter; fortunately, however, neither ship

received damage in the hull."

Captain Landais's conduct during this

accident left much to be desired, and it was solemnly attested by the

officers of the squadron that, instead of giving the requisite orders to

prevent the collision, and afterwards remaining on deck to assist in the

extrication of the Alliance, he went below to load his pistols. "The

base desertion of his station when the fate of his ship was at hazard

showed a shrinking from duty and responsibility, and a want of presence

of mind; whilst the search for his pistols, real or affected, to be used

against his commanding officer, evinced a braggart disposition to shed

blood which was doubtless assumed to cover the timidity with which the

jeopardy of his ship had affected him. This anecdote will be found very

characteristic of the man in after scenes of much greater peril."

The squadron reeked with insubordination,

and Lan dais was so hated that he and his officers "were ready to cut

one another's throats; the crew had mutinied on the voyage from America,

with Lafayette on board, and once in port the first and second

lieutenants deserted. There had been trouble on the Bonhomme Richard

among the English prisoners who enlisted with Jones as Americans, in

order to escape from their loathsome prisons, and with the ultimate hope

of getting home once more. "Two quarter-masters were implicated as

ringleaders in a conspiracy to take the ship. It was necessary to hold a

court-martial for the trial of these offenders; and a knowledge of the

circumstances thus reaching Al. de Sartine created a distrust with

regard to the efficiency of the Bonhomme Richard, which gave Jones great

annoyance. The result of the court-martial was, that the quarter-masters

were severely whipped instead of being condemned to death, as Jones,

from a letter written about this period, seemed to have apprehended."

The return of the squadron to Brest for

repairs was, in the end, a great benefit to the Commander, enabling him

to enlist those American seamen just exchanged by Lord North's orders

for the prisoners kept by Jones on the Patience in Brest harbour.

Undoubtedly this new addition to the Richard's fighting force aided

Jones to make one of the most brilliant victories in the annals of naval

warfare; without them, and left to the hazards of his mongrel crew, he

might have chosen to sink with his ship, rather than "fail and fall"

They were the best to be found, these sturdy Yankee tars, such as "Good

old Fighting Dick Dale," to whom he left the sword of honour given him

by King Louis; Nathaniel Fanning, who wrote a vivid description of the

battle; Henry Lunt and John Mavrant, whom the Captain eulogises in his

journal.

It was my fortune to command many brave

men, but I never knew a man so exactly after my own heart or so near the

kind of man I would create, if I could, as John Mayrant." These and a

score of others formed the fighting backbone of the crew; fearless,

daring, hold sailors, who were afraid of nothing human, satanic, or

divine.

For some reason the name Bonhomme Richard

seemed to please the fancy of the men. Jones, too, had a very persuasive

way, and would walk for an hour or more on the pier with a single sailor

whom he was desirous of enlisting, and rarely failed of success. Placing

scanty reliance on the untried French, Portuguese and Lascars, who, with

the released English prisoners, formed a large proportion of his crew,

he drafted them on to other ships of the squadron, manning the Bonhomme

Richard with a hundred and fifty American sailors and officers, who, in

case of trouble, would be in sufficient proportion to dominate the ship.

There has been such strong testimony

recorded about Jones's dislike to the use of the cat-o'-nine-tails that

the story told by John Kilby, one of the released prisoners enlisted, is

not without interest. It must be kept in mind that the narrative was

written from memory some thirty years after the events happened, and

memory is not always infallible. All through the story John Kilby's

remembrance of the names of those who were his daily associates is so

erroneous that it is not easy to believe him reliable on other events He

says—

"We all went on board of the ship

Bonhomme Richard. The first sight that was presented to our view was

thirteen men stripped and tied up on the larboard side of the

quarter-deck. The boatswain's mate commenced at the one nearest the

gangway and gave him one dozen lashes with the cat-o'-nine-tails. Thus

he went on until he came to the coxswain, Robertson by name. ('These men

were the crew of the captain's barge, and Robertson was the coxswain.)

When the boatswain's mate came to Robertson, the first lieutenant said :

'As he's a hit of an officer, give him two dozen.' it was done. Now it

is necessary to let you know what they had been guilty of. They had

carried the Captain on shore, and as soon as Jones was out of sight,

they all left the barge and got drunk. When Jones came down in order to

go on board, not a man was to be found. Jones had to, and did, hire a

fishing boat to carry him on board. Here it will he proper to observe

that, some small time before, Jones had entered seventy-two men (English

prisoners) who had been released from the prison of Denan (Dinan?) in

the inland part of France. Nearly all of them were good seamen, and the

crew of the captain's barge was selected from their number."

These released prisoners, whom Jones

enlisted and brought from l'Orient, paying their travelling expenses out

of his own pocket, were mostly " rated as warrant or Petty Officers upon

the reorganisation of the Richards crew."

While the squadron lay inactive for six

weeks at the Isle of Groix, Franklin, who had not learned of the

accident to the Richard and Alliance, sent Jones a letter with

directions for the cruise. The doctor directed that the fleet should

cruise on the west coast of Ireland, "establish your cruise on the

Orcadcs, the Cape of Derneus, and the Dogger Bank, in order to take the

enemy's property in those seas.

The prizes you make, send to Dunkirk,

Ostend, or Bergen in Norway, according to your proximity to either of

these ports." The cruise was to end at the Texel. This letter was

crossed by that of Jones, informing the doctor of the accident to the

Ric/zard. The Commodore had many complaints for the ear of his friend,

but Franklin tries to pacify him with the suggestion, that as the cruise

was to end at the Texel, he might at last accomplish his great desire,

and get command of the Indien.

Shortly before sailing, the squadron had

been joined by two privateers, the Monsieur of forty guns and the

Grandville of fourteen. They offered to bind themselves "to remain

attached to the squadron; but this the ' disinterested commissary would

not Permit. The consequences were soon obvious; the privateers remained

attached to the squadron exactly as long as it suited themselves."

The Monsieur is said to have been owned

by Marie Antoinette's ladies of honour, the chief share belonging to the

Duchesse de Chartres; and was commanded by a captain in the navy,

Philippe Gueçlloe de Roberdeau, who warned Jones that Landais would

betray him at the first opportunity. His hatred for Landais is given as

Roberdeau's reason for afterwards leaving the squadron; and in 1780 he

refused Lanclais's challenge on the grounds that the latter was not

entitled to the privileges of a gentleman.

"Having given the necessary orders and

signals and appointed various places of rendezvous for every captain in

case of separation, Commodore Jones sailed from the road of Groix on the

14th of August, exactly one day short of the time he had been desired to

come into the Texci, after ending his cruise; so uncertain and

precarious are all nautical movements.

"This force might have effected great

services, and done infinite injury to the enemy, had there been secrecy

and due subordination; Captain Jones saw his danger; but his reputation

being at stake, he put all to the hazard."

Authorities agree that this cruise of

fifteen days left an indcradicable impression on naval history. "Other

cruises have been marked at least by discipline, subordination, and zeal

of commanders for the common cause. This one, from beginning to end, was

distracted by insubordination that in any regular navy would have been

condemned as mutiny and punished by shooting on deck or hanging at the

yardarm."

Four days out the squadron on the 18th

captured the Verwagting, a large Dutch ship, taken some 'days before by

an English privateer. The effects of the "Con cordat" began to show, for

though Jones, the senior officer, was within hail, the captain of the

Monsieur, who had taken the Dutch ship and removed from her what he saw

fit, put a prize crew on board, ordering her into port. Jones

countermanded this order, sending her to l'Orient, which so displeased

de Roberdeau that he departed under cover of night, and the squadron saw

him no more. On the 23rd they made Cape Clear, and the Pallas took the

brigantine Mayflower, with a cargo of butter, salt meats and fish, bound

from London to Limerick, sending her to l'Orient; and the Fortune of

Bristol was captured and sent to Nantes.

On the 23rd Jones had a most annoying

misadventure. Having sent his boats to capture a brigantine, it was

necessary to keep the Bonhomme Richard from drifting into a dangerous

bay while awaiting their return; and, as there was not enough wind to

handle the ship, the barge was ordered ahead to tow. The ex-prisoners

who manned the barge had been looking for just such an opportunity. They

waited until dusk, cut the tow-line, and, having overpowered the two

American petty officers, made for the shore. They were fired at without

effect from the Bonhomme Richard, and the master, Lunt, on his own

responsibility, lowered a boat and gave chase. Lunt was unable to come

up with the fugitives, and presently both boats disappeared in the fog,

and the Cerf, which was sent to find them, did not return or make for

the rendezvous appointed. This took two of the best boats and

twenty-three men from the Bonhomme Richard, and signal guns were fired

all night, as the fog did not lift.

The following afternoon Landais came

aboard, proceeding to heap insults on his commanding officer, "affirming

in the most indelicate language" that the boats had been lost through

Jones's "imprudence in sending boats to take a prize ! It is easy, after

this scene, to believe all the allegations made as to the unprecedented

and extraordinary conditions with which Paul Jones had to cope on this

cruise.

There was frightful tension during the

scene; how, with this insult and provocation, Paul ever controlled his

fiery temper, can only be explained by his paramount desire to carry

through the cruise he had planned, so he put an iron-handed restraint on

himself, and grimly waited. Landais sneeringly ignored the statements of

Colonels Chamillard and Weibert, who tried to drum into his head the

fact that the barge was towing the ship, and not chasing prizes. It was

his petty jealousy and revenge for not being allowed to chase the day

before, "and approach the dangerous shore . . . where he was an entire

stranger, and there was not wind enough to govern a ship." He announced

himself to be "the only American in the squadron, declaring, from now

on, that he, holding a commission as captain in the United States Navy,

given him by Congress, was answerable to no one, and would act as he saw

fit."

There was no end to Landais's insolence.

A few days later they lost a fine letter-of -marque because, at the

critical moment, he ran up the American flag on the Alliance, instead of

showing English colours, as the IJo;thomme Richard was doing. When the

captain of the letter-of-marque saw this, he instantly threw his

despatches overboard, beyond reach of the enemy. Incidents of this kind

happen frequently, as we gather from the voluminous correspondence

between Franklin and Jones. Landais hated Paul Jones with the hatred of

a disgraced and dishonour- able man for one whose honour was

untarnished, who had no stain on his past, and nothing to cloud his

future; and Landais knew that only the exigencies of war allowed him to

be tolerated, much less treated with friendliness, by officers of the

service he had disgraced. The hasty action taken by Congress had placed

all parties in an exceedingly awkward position.

The most important project planned by

Jones for this cruise was the attack on Leith, from which town he hoped

to levy some £200,000. So certain was he of success, that the papers of

capitulation were drawn up in due form ready for the signature of the

provost and his henchmen, who were to be allowed half-anchor for

reflection before producing the ransom. Leith was unguarded by cannon at

its port, and soldiers for defence would have to be brought from

Edinburgh, a mile distant. Luck and the wind were against Jones, for a

cutter brought in news of his appearance on the Scotch coast, where,

some thirty years afterwards, "the prodigious sensation caused by the

appearance of Paul Jones in the Firth of Forth is hardly forgotten on

the coast of Fife." His arrival on a Sunday morning caused wild turmoil

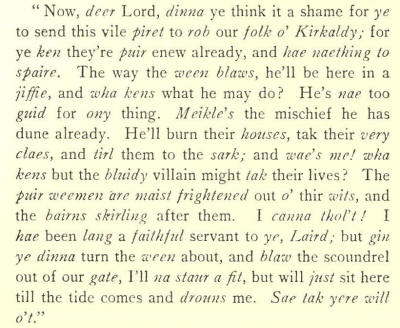

in the hearts of the kirk-going population of the "lang toun o' Kirkaldy";

and one dissenting minister, Mr. Shirra, who had a peculiar and informal

manner of intimating his wishes to the Almighty, abandoned all idea of

going to his pulpit, and, seating himself in an armchair, like Canute by

the edge of the sea, proceeded to invoke the aid of heaven in the

broadest Scotch.

And, till the day of their deaths, his

faithful parishioners could not have been argued out of their belief

that it was solely owing to the efforts of the Dominie that a severe

gale came up and forced the ships to put to sea for safety, as already

one of the prizes had been sunk by the severity of the weather, and the

Bonhomme Richard had sprung a mast. For years afterwards, when the old

clergyman was complimented on the efficacy of his prayer, he modestly

disclaimed any part in the happening, always saying: "I prayed—but the

Laird sent the ze'een."

Excited crowds assembled on the heights

above Kirkcaldy, and on the sandy beach. At one time the Bonhomme

Richard was within a mile of the shore, and with glasses the renowned

Commander could he clearly seen, and is described as "being dressed in

the American uniform with a Scotch bonnet edged with gold—as of a middle

stature, stern countenance and swarthy complexion."

The failure to attack Leith ranked as

another of his disappointments. There was incessant friction with

Landais and with Cottineau, captain of the Pallas, who ransomed a prize,

which no one in the squadron had authority to do, as they were

considered the property of the King of France. After the gale the

squadron made sail to the southward, captured some prizes, and sighted

an English fleet, which kept so near shore in the shallow water Jones

dared not attack. He then signalled a pilot, who, believing the Bonhomme

Richard to he an English ship, brought the news that a king's ship lay

at the mouth of the Humber, waiting to convoy a fleet of merchant ships

to the north. The pilot innocently gave Jones the private signal, with

which he nearly decoyed these ships out of port. They had started to

answer the signal, "when the tide turned, and an unfavourable wind made

them put hack. Jones decided the position was too dangerous to hold

unsupported, and the Pal/as not being in sight, steered to join her off

Flamborough Head."

Jones had explained to Cottineau, a few

days after his failure to attack Leith, similar projects in regard to

Hull and Newcastle; but Cottineau had no desire to take those wild

chances in which his intrepid commander revelled, and dissuaded Jones

with every argument he could summon. Afterwards Jones declared he would

have undertaken it without the help of the Pallas, so sure was he of his

junior officers, but for the reproach which would have "been cast on his

character as a man of prudence had the enterprise miscarried. It would

have been, 'Was he not forewarned by Captain Cottineau and others?'"

Cottineau croaked that two :days more on the coast would surely lead to

their capture, and told Colonel de Chamillard that unless Jones left

next day, the Pallas and Vengeance would abandon him." Thanks to the

thoroughness with which the "secret" orders had been made common

property, every man Jack in the squadron knew the day appointed for

rendezvous at the Texel, and, seeing no opportunity for enriching

themselves, clamoured to put into port again.

Jones, on this cruise, may be compared to

a man trying to run with a heavy shot chained to his leg. The fatal

"Concordat" compelled him to act in concert with those whom he should

have dominated. He possessed in a marked degree that clairvoyant gift of

knowing, to the smallest detail, the result of his plans. His perfect

confidence in his abilities rnac him as certain of success as he was of

the rising and setting of the sun. He could " hitch his waggon to a star

" without misgiving ; but those with whom lie had to deal were unable to

rise to his heights.

I sailed, in my time, with many captains;

but with only one Paul Jones," his acting gunner, Henry Gardner wrote.

"He was the captain of captains. Any other commander I sailed with had

some kind of method or fixed rule which he exerted towards all those

tinder him alike. It suited some and others not; but it was the same

rule all the time and to everybody. Not so Paul Jones. He always knew

every officer or man in his crew as one friend knew another. Those big

black eyes of his would look through a new man at first sight, and,

maybe, see something behind him."

It was the misfortune of Paul Jones, in

almost every important crisis of his life, to be either clogged by the

timid counsels of those about him, whose genius and courage could not

keep pace with his or to be thwarted by the baser feelings of ignoble

rival- ship. In no other service than that of America, still struggling

for a doubtful existence as an independent state, and without either

power or means to enforce dime obedience throughout the gradations of

the public service, could such insubordination as was displayed by his

force have been tolerated."

Paul was to have his opportunity,

however, though he little dreamed what the morrow was to bring forth

when he closed his tired eyes on the night of September 22, 1779. |